31 minute read

Empowering Families to Advocate for their Children in the PICU - Mary Schafer MSN, RN, CCRN, CPNP

Empowering Families to Advocate for their Children in the PICU

Mary Schafer MSN, RN, CCRN, PNP

Advertisement

Background:

The ABCDEF bundle (Table 1, top right) is an initiative from the Society of Critical Care Medicine aimed to minimize the harmful effects of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption during the patient’s stay in the intensive care unit (ICU). The bundle’s overall goal is to empower the multi-professional team to improve patient and family outcomes through evidence-based care to reduce the risk of long-term consequences associated with an ICU stay.

Each letter of the ABCDEF bundle represents an area of focus when caring for critically ill patients. The A represents Assess, prevent and manage pain; B is for Both spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing; C is Choice of analgesic and sedation; D is for Delirium; E is for Early mobility, and F is for Family engagements. In this article, we will examine the adaption of Family Engagement and Empowerment. The Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) had previously incorporated families into care through family-centered rounding; however, there was an opportunity for improvement. A representative from the Family Advisory Council was recruited to assist with strategies to improve family engagement, empowerment, and support. Family input was elicited as to what interventions could improve the ICU experience. After several meetings and performing an evidence-based literature review, the decision was made to create a PICU brochure and a PICU Diary.

Evidence:

Critical Illness can be overwhelming for patients and their families and can lead to adverse psychologic outcomes such as anxiety, acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress, and depression. This combination of complications has been entitled Post-intensive Care Syndrome- Family (PICS-F).

Family-centered care supports the presence of family in the ICU and their involvement in their child’s care. Family-centered care encourages timely and effective communication between ICU staff and can help manage the family’s stress associated with a critical illness. Studies have shown that family engagement plays a crucial role in reducing the long- and short-term consequences of an ICU stay (Davidson et al. 2017). Although we cannot change the demographic risk factors of PICS-F, we can change our culture to decrease the risk factors that increase the family’s potential for developing PICS-F. Research shows that family members of critically ill patients who talked about their feelings and had social support had lower anxiety levels. Parents, who perceive ICU staff communication as open, complete, and comforting had a positive experience. (Coats, 2018.) The PICU had open visiting hours for primary caregivers and family-centered rounds that improved family satisfaction and increased family engagement. The ABCDEF team’s literature review revealed that education programs, support programs, and spiritual/integrative therapies helped reduce the family’s stress level. The ABCDEF workgroup decided to start by developing an informative brochure called “Caring for you and your child in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.” A PICU diary was also created to help reduce the family’s anxiety, depression, and stress. This diary allows the family to track their child’s progress, especially when they needed to leave their child alone in the PICU.

Initiative Details:

Family-centered rounds have been part of our PICU culture for many years. The multi-professional ABCDEF Team decided to start with a PICU Brochure and a PICU Diary to enhance patient and family engagement, empowerment, and support. The brochure, once finalized by the workgroup, was brought to the Family Advisory Council and the marketing department. The final version was entitled Caring for you and your Child in The Pediatric ICU and includes: • PICU team composition and culture of support • Promotion of self-care of the caregivers • Resources for Family Support including information regarding our siblings club and Integrative Therapies • Guidance to the family on how to assist in their child’s recovery • Encouragement to participate in rounds, request family meetings, and state what matters to them. • Encouragement to speak up for safety on essential aspects of care such as medication reconciliation, allergies, isolation precautions. • Information on ICU strategies to improve neurocognitive and functional outcomes in critically ill patients utilizing the elements of the ABCDEF bundle and how parents can participate and advocate for their child

The ICU Diary was created for families to have a place to keep track of their child’s care. The diary is a composition book divided into two sections, with the first section filled out by the parents. The first page has open-ended questions, including “I like to be called,” “My normal bedtime is,” “My favorite food is,” “My favorite color is,” and “My favorite TV show/movie is.” On the second page of the diary, parents are asked to write any information about their child that they think may be helpful when they are not by the bedside. The next pages are for the interprofessional team to write updates, test results, questions, and answers to questions parents had previously asked. Parents are encouraged to personalize the diary to meet their specific needs.

Achieving Zero Harm through Prevention of Peripheral IV Infiltration and Extravasation

Lianna Mashkovich MSN, RN, CPNP-PC identifying, categorizing, and treating PIVIEs. In April 2017, a Introduction the mission to mitigate complications and harm associated with

Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) admits over PIVIEs. 11,000 pediatric patients annually. More than 90% require Solutions for Patient Safety (SPS) is a national organization peripheral intravenous (PIV) access. PIV access can lead to of pediatric hospitals that share an objective to eliminate harm complications that affect patient safety, increase patient length of children experience during their hospitalization. SPS collects stay, and decreases patient satisfaction. A common PIV com- data, shares methods, and highlights interventions with negative plication, peripheral intravenous infiltration, and extravasations and positive outcomes to find appropriate solutions for safety (PIVIEs) occur at a rate of 3.64 per 1,000 inpatient admission issues affecting pediatric patients. Working in conjunction with days. In January 2017, CCMC detected an increase in harm to SPS, CCMC began adopting the best practices to identify, prepatients due to PIVIEs. This discovery prompted a response vent, and treat the occurrence of PIVIEs. in training healthcare providers who were knowledgeable in SPS has defined the categories of harm caused by injury due The Impact of Nurse Fellowships

from page 16

taking on independent care. CRNs do not have their own patient assignment. They mentor, coach, and supervise the fellow on the unit for six months. CRNs oversee assignments, workload, time management, prioritization, documentation, and skill development. Their primary function is to offer support, guidance, and feedback to assist the fellow in acclimating to their role. The fellow is evaluated using documentation that defines clinical practice expectations and is given feedback regarding these expectations. Utilizing weekly resource records, the fellow is provided feedback about progress, ongoing goals, and specific competencies. Evaluation of the fellows, by the CRN, incorporates ongoing discussion of the orientation goals, assistance with successful completion of nursing competencies, and consistent dialogue regarding the fellow’s process. This process fosters collaboration and teamwork, helping sustain the fellow as they evolve to independent practice.

Results:

The PCCNFP yielded a 91% retention rate for those who completed the fellowship in the past three years. Prior to this initiative the retention rates was at 50.1%. This represented an overall 81.6% increase. Additionally, RN satisfaction and engagement scores remained in the top “Team Index 1” ranking for five years. These factors all contributed to positive patient outcomes evident by this PICU receiving the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) Silver Beacon Award for Excellence in 2017 and 2020. Discussion:

The implementation of a fellowship program in the PICU helps novice nurses transition to safe, independent practice. Understanding that most nursing recruits are new graduates, nurse leaders need to provide them with a formal, evidenced-based program. Additionally, most nursing students are not allowed to train in a PICU while in school. For many of our new nursing hires, this was their first time experiencing the PICU. Fellowship programs not only improve retention rates but posiHospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Team was assembled with tively impact nurse satisfaction and engagement in their practice area. They foster a successful transition into independent practice by increasing the competence and confidence of a novice nurse. Further studies are required to determine long-term retention rates for graduate nurses completing a nurse fellowship program and determine their impact on patient outcomes.

References

Benner, P. (1981) From novice to expert. The American Journal of Nursing, 82(3), 402-407.

Bradley, V. (2017). The effect of a new graduate registered nurse residency program on retention. Nursing Theses and Capstone Projects.

Garrison, F. W., Dearmon, V., & Graves, R. J. (2017, March). Working smarter: Building a better nurse residency program. Nursing Management, 50-54.

Van Camp, J. & Chappy, S. (2017). The effectiveness of nurse residency programs on retention: A systematic review. The

Maria Marchelos MSN, RN, CCRN-K, NEA-BC Nurse Manager, PICU CohenChildren’s Medical Center

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, 106, 128-144. 26

Kathleen Schmidt MS, RN, PNP, CCRN Nurse Educator Cohen Children’s Medical Center

to a PIVIE as mild, moderate, and serious.

Serious (Severe) Harm includes, for example, PIVIE requiring fasciotomy or with deep partial thickness. Moderate PIVIEs include those with partial-thickness burns and those with between thirty to sixty percent swelling. Mild harm consists of swelling of less than thirty percent.

In response to increased harm from PIVIE, SPS has developed a prevention bundle, a set of guidelines that have shown to mitigate harm. Some of these bundle components include, assessing PIVs every sixty minutes and measuring the infiltrate for the percentage of swelling. The assessment consists of touching, looking, and comparing the limb. The PIV site is compared to the opposite limb to determine if there is swelling. Measuring the PIVIE included measure the length of the limb that the PIV is placed, and the longest portion of swelling of the PIVIE and calculating a percentage. Education to families is the last piece of the bundle and included educating families to touch, look, and call if they think there is something wrong with the PIV.

In January 2018, the PIVIE HAC team at CCMC conducted a literature review to find a treatment that could reduce the severity of the injury caused by PIVIEs. In the review, it was noted that hyaluronidase had multiple purposes in the patient care setting. Hyaluronidase can be used for subcutaneous rehydration therapy when it is difficult to obtain a peripheral IV. It was also noted that when injected subcutaneously around an infiltration area, hyaluronidase helped facilitate the reabsorption of fluid into the capillary bed from the surrounding tissue. It can be used as an antidote for infiltrates of IV fluids and a wide variety of IV medications. This helps decrease tissue damage and reduces the risk of tissue necrosis. It was concluded that hyaluronidase would be used as the first-line treatment of PIVIEs and continues to be the most common antidote used at CCMC for infiltrations.

Starting in February 2018, the PIVIE HAC co-chairs trained the PIVIE HAC champions in hyaluronidase administration for PIVIEs. In turn, the PIVIE HAC champions trained nurses and providers on the inpatient units of CCMC in hyaluronidase administration. Hyaluronidase’s adoption for the treatment of moderate and serious infiltrates has decreased the rate of morbidity, length of stay, and need for invasive interventions.

Methods

To ensure guidelines and methods were being followed, the PIVIE HAC team created a “Post PIVIE Data Collection Tool.” Nurses and providers have been instructed to utilize the tool to document the incidence of PIVIEs. The data collected by the tool is analyzed in several ways. The data collected by the tool is • Used to monitor the efficacy of the HAC’s efforts to mitigate the occurrence of moderate and severe PIVIEs • Submitted to SPS for national analysis and tracking • Provide training and feedback to nurses and providers when the PIV Prevention Bundles and treatment are not followed properly

In addition, PIVIE HAC champions conduct real-time audits of PIV assessment documentation, inspection of PIV insertion site, and family education. These audits identify the need for re-training the staff to follow the SPS PIV Prevention Bundle guidelines. Results

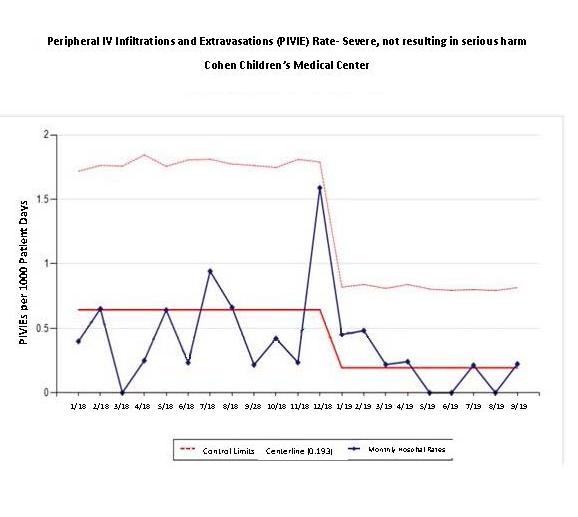

Since the PIV Prevention Bundle implementation, there has been a significant reduction in Moderate and Serious PIVIE Harm. CCMC’s Moderate infiltrates centerline has decreased below the national average as reported by SPS (Figure 1, above). CCMC has dropped the centerline of the average number of Moderate infiltrates from 2.4 per 1,000 patient days in 2018 to 1.351 per 1,000 patient days in 2019. The national average of Moderate infiltrates per SPS statistics is 1.889 per 1,000 patient days.

The serious infiltrates centerline has decreased below the national average, as reported by SPS (Figure 2, below). The centerline of the average number of Serious infiltrates also decreased from 0.6 per 1,000 patient days in 2018 to 0.193 per 1,000 patient days in 2019. The national average of Serious infiltrates per SPS statistics is 0.428 per 1,000 patient days.

Discussion

The PIVIE HAC has been instrumental in the efforts to achieve SPS’s objective of zero harm. The PIVIE HAC has successfully educated nurses and providers in properly assessing PIVs, identifying infiltrates early, and providing timely and appropriate interventions, including hyaluronidase administration. These interventions have decreased the number of Moderate and Serious harm that patients sustain, improving patient safety and patient satisfaction.

continued on page 30

from page 7

Outcomes

The St. Agnes Healthcare Club has been running successfully for three years, and the outcomes for promoting nursing to a new generation are promising. The first year the club was introduced saw a very enthusiastic group of juniors and seniors who had a significant interest in following either nursing or an alternative healthcare tract. The entire first cohort of students entered college in either a nursing or an undergraduate medical program. The second-year saw a younger cohort of students, mostly in the 10th grade, interested in nursing, or were curious about the program. Many of these participants are still in High School and have not applied to college thus far. In time we will see how effective the program was in solidifying their STEM connection. A good indication of these second-year cohort girls’ continued interest is that some have come back during the third year to act as facilitators. Unfortunately, with the Covid-19 outbreak and closure of in-person teaching, the third cohort of students could not finish the program. However, the first half of the year successfully reflected a high attendance record and enthusiastic participation.

Conclusion

As a STEM education leader, it is important that the students are excited about what they are learning. Through this program, students learn that nursing is much more than a job. They learn that it is a lifestyle that is conveyed by what nurses do as professionals, as community leaders, as educators, and as mentors. Hopefully, through the STEM connection, they will be inspired to become the nurses of the future.

References

American Nurse Association. (2020). Healthy Nurse Healthy Challenge. HNHN | home. https://www.healthynursehealthynation.org/ American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. ANA. https://www.nursingworld. org/coe-view-only

Kelley, T. R., & Knowles, J. G. (2016). A conceptual framework for integrated STEM education. International Journal of 28

STEM Education, 3(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594016-0046-z Northwell Health. (2014). SPARK Challenge. https://vportal. northwell.edu/cvpn/aHR0cHM6Ly9pbnRyYW5ldC5ub3J0aHdlbGwuZWR1/employees/PulseDocuments/Spark%20 Calendar%20of%20Events.pdf. https://vportal.northwell.edu/ cvpn/aHR0cHM6Ly9pbnRyYW5ldC5ub3J0aHdlbGwuZWR1/ employees/PulseDocuments/Spark%20Calendar%20of%20 Events.pdf

Shirazi, F., & Heidari, S. (2019). The relationship between critical thinking skills and learning styles and academic achievement of nursing students. Journal of Nursing Research, 27(4), e38. https://doi.org/10.1097/ jnr.0000000000000307

St. Agnes Academic High School. (n.d.). Science, technology, engineering, and math. https://www.stagneshs.org/apps/ news/show_news.jsp?REC_ID=416593&id=1

Van den Hurk, A., Meelissen, M., & Van Langen, A. (2018). Interventions in education to prevent STEM pipeline leakage. International Journal of Science Education, 41(2), 150164. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1540897

Yvonne Hernandez MSN, RN, CPEN, Clinical Nurse, Pediatric Emergency Department, Cohen Children’s Medical Center

from page 24

in these programs.

Funding and Support of the Initiative

While all our providers and practitioners are on staff, there is limited funding available for these programs, which poses an ever-present challenge to our executive team to find creative solutions to support these programs and events. We rely heavily on the generous donations from the community and any available grant funding. We were recently awarded a $1000 grant from the Beryl Institute. These welcomed funds will go toward purchasing a second electronic massage chair for our Recharge Room, which will be available to all in early 2021.

Discussion

The personality trait of hardiness has been found to buffer or lessen the negative effects of stressful events or adversity (Liu, 2019). Leaders must fully appreciate and analyze how the heroic response to COVID-19, mounted by our interprofessional teams, changed everything. Each healthcare organization is challenged today (post-COVID) with creating a healthy work environment for all to work and practice. Each organization must accept the challenge of creating a culture in which staff can actively engage in self-care and mental health activities as openly as they have been encouraged to participate in ongoing professional development programs. As Dr. Jean Watson, PhD, RN, teaches in her nursing theories, we must show ourselves the same loving-kindness as we do our patients and families. We must place ourselves (the caregivers) at the center of the model of care and “Minister to our Basic Physical, Emotional, and Spiritual Human Needs” if we are to “Co-Create a Healing Environment for the Physical Self which Respects Human Dignity.”

References and Resources

American Association of Critical Care Nurses. AACN Standards for standards for establishing and sustain a healthy work environment; a journey to excellence 2nd edition. 2016: www.aacn.org

Bailey, K., Madden, A. Research Article, What makes work meaningful or meaningless. MIT Sloan Management Review. 2016: Summer: 52-61.

Bernhard, T. Self-care in an uncertain world. Tricycle. 2020: 30 (1) 36-37.

Bogue, R., Carter, K. A model for advancing nursing well-being: future directions for nurse leaders. Nurse Leader. 2019: (17): 526-529.

Centre for Confidence and Wellbeing http://positivepsychology.org.uk/centre-for-confidence-and-well-being/

Craig. H. Resilience in the workplace: how to be more resilient at work. (2020). An online article found on the world wide web. https://positivepsychology.com/resilience-in-the-workplace/

Kennedy, K., Campis, S., Leclerc, L. Human-Centered leadership: creating change from the inside out. Nurse Leader. 2020: 8 (3): 227-236.

Kobayashi, M. Nurse leader rounding: a view from the front. VOICE of Nursing Leadership.2020: 18 (4): 20-21.

KPGM. COVID-19 and the American worker. (2019) An online article found on the world wide web. https://advisory. kpmg.us/articles/2020/covid-american-worker.html?utm_ source=google&utm_medium=cpc&mid=m-00003181&utm_ campaign=c-00088586&cid=c-00088586&gclid=Cj0KCQjwtZH7BRDzARIsAGjbK2b3el6pi20t9OxlG-j8ESHdCFCPdb1mRnb3z4q9gsXSriqD-m6CbOEaAhgiEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

Liu, A. Making Joy a Priority at Work. Harvard Business Review. (2019). An online article found on the world wide web. https://hbr.org/2019/07/making-joy-a-priority-atwork?utm_campaign=hbr&utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=social Repenning, N., Kieffer, D., Astor, T. The most underrated management skill. MIT Sloan Management Review. 2019: 58 (3): 39-48.

Richardson, J., Ingoglia, C. Building Organizational Resilience in the Face of Covid-19. The National Council for Behavioral Health. An online article found on the world wide web. file:///C:/Users/Phyllis/Downloads/Building_Organizational_Resilience_in_the_Face_of_COVID-19.pdf

Steinbinder, A., Sisneros, D. Achieving uncommon results through caring leadership. 2020: 18 (3):243-247. The Watson Caring Science Institute. https://www.watsoncaringscience.org/

Phyllis S. Quinlan PhD, RN, NPD-BC Program Manager for Clinical Transformation, Internal Coach, Administration Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Sofia Agoritsas MPA, FACHE Associate Executive Director Hospital Operations Cohen Children’s Medical Center.

Cari Quinn RN, MSN, NEA-BC Executive Director Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Next Steps

The PIVIE HAC will continue educating champions, staff nurses, and providers on the PIV Prevention Bundle, proper assessment and interventions when PIVIEs occur, and proper administration of hyaluronidase. In collaborating with the Pediatric Pharmacy, the creation of a new hyaluronidase order-set is in development. The team has also put together an interactive virtual learning module to standardize training and communication throughout the Northwell Health Pediatric Service Line.

References

Children’s Hospitals Working Together to Eliminate Harm. (n.d.). Retrieved August 19, 2020, from https://www.solutionsforpatientsafety.org/

Lexicomp Online, Pediatric, and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs Online, Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc. Retrieved from http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home

Odom, B., Lowe, L. & Yates, C. (2018). Peripheral infiltration and extravasation injury methodology. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 41(4), 247-252.

Taylor, J.T. (2014). Implementing an evidence-based practice project in the prevention of peripheral intravenous site infiltrations in children. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 38(6), 430-435. Lianna Mashkovich Treadwell, T. (2012). The management of intravenous infiltraMSN, RN, CPNP-PC tion injuries in infants and children. Ostomy Wound ManageClinical Nurse ment, 58(7), 40-44. Cohen Children’s Wilt Major, T., & Huey, T.K. (2016). Decreasing iv infiltrates Medical Center in the pediatric patient – system-based improvement project. Pediatric Nursing, 42(1), 14-20.

Changing the culture in the Pediatric ASU

from page 28

Our future goal is to expand this initiative and place PIVs on Carol Creeron BSN, CPN,

all patients above 10-years-old or greater than 40 kg. We will continue to work with the anesthesiologists to ensure that we are placing appropriate gauge PIVs in preferable anatomical loca-

tions. Clinical Nurse, PACU, Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Acknowledgments:

We would like to express our appreciation to all of the people who were instrumental in making this initiative a success; most importantly, we would like to thank the PASU nurses; this project would not have been possible without your enthusiasm and willingness to participate.

Special thanks to the Anesthesiologists for educating and encouraging this change, especially to Michelle Kars, MD, who was the inspiration behind this initiative and always an excellent resource for us. Also, to Alison Beach, MSN, RN, from nursing professional development for assisting with educating the PASU staff for PIV competencies. Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Additional appreciation to Ann Shea, MSN, RN, for facilitating and supporting this project.

References

Nisbet, G., Lincoln, M., & Dunn, S. (2013). Informal inter-professional learning: an untapped opportunity for learning and change within the workplace. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), 469–475. doi:10.3109/13561820.2013.805735z. Johansson, C., Åström, S., Kauffeldt, A., Helldin, L., & Carla study of competing values in a psychiatric nursing context. Health Policy, 114(2-3), 156-162. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.07.014

Haley Holcman BSN, CCRN, Clinical Nurse, PASU, Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Fran Weingartner BSN, RN, Assistant Nurse Manager, PASU ström, E. (2014). Culture as a predictor of resistance to change:

Melissa Duffy MSN, CPNP-PC, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, PST Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Artwork by Tasfia Suha, New Hyde Park High School donated as part of a school project for healthcare workers.

Adult patients were not as different as once assumed

from page 5

confused was up in the air. I bent down to be at her level and smiled, wearing my mask, of course. The most unbelievable thing happened - she smiled back, without seeing my mouth smile. When the elevator door opened, I waved her goodbye. I went to the ladies room and stood in front of the mirror, smiling with my mask on; whether it’s my scrunching cheeks or my eyes, my face smiled, despite wearing a mask. The way she looked at me, maybe for that tiny moment in time, I was her hero. She may have been frightened initially, but we shared a smile, and her expression was no longer questionable; she looked happy. What I am learning every day is that we are all heroes. Every single employee in our facility was a hero for walking into this building during the pandemic. Being a hero does not mean that extraordinary measures have to be taken. Being a hero could be as simple as helping a lost visitor in the hallway or making a frightened girl smile. For that moment in time, they needed help, and you were there and potentially their hero for that moment. We were all nervous and scared to leave our families. We were so worried to spread the virus to our loved ones. Homeschooling our children was challenging, and we have no idea what will happen in the next six months. What we do know is that we have each other, and once you enter this building, we are all surrounded by heroes, brave, and courageous healthcare heroes.

As you get dressed and put on your badges day in and day out, remember you have the potential to be someone’s hero today, and you already are to your coworkers, simply by showing up. I am so thankful for all of my coworkers. I felt such support in the adult hospital when I saw multiple nurse educators and even my Chief Nursing Officer from Cohen’s. This bought a smile to my face on some of the most difficult days. The comradery and teamwork I felt was extraordinary. I do not look forward to another pandemic, but if it happens to come back, I am confident that we are ready and all willing to fight again. I also want to thank all of the LIJ staff that supported me and believed in my skills, especially Kevin Cunningham and Garry Ritter.

Renata Schillizzi MSN, FNP-BC, CCRN, Family Nurse Practitioner, PST Cohen Children’s Medical Center

from page 9

setting had proven effective in decreasing noise and improving patient experience related to a restful night (Boehm, H., & Morast, S. 2009). Quiet time on the unit was initiated with an overhead announcement to the entire unit. The team collaborated with the Unit Receptionists (UR) to implement these changes by creating a script (figure 1). The script prepared the patients and families for “Quite Time” in the evening before the overhead announcement. The development and incorporation of the UR script was a unique component to the interventions. Unit receptionists were a part of the team developing the script, and all URs received education on the script before implementation. The script allowed for standardization throughout the unit. This consistency of information to all families was reported to be helpful, especially when in a shared room. Also noted to be beneficial was alerting families ahead of time to ensure that the message was clear, understood, and received well. The Unit receptionist also offers amenities at the time of delivering the script. These amenities include, eye masks, headphones, and the option of white noise/ soothing sounds on the patient’s TV in the room. These helped relieve some of the common issues raised in the patient survey, such as using headphones to prevent hearing the noise from a roommate’s TV and eye masks when lights are used at night to perform patient assessments.

As part of the admission process, parents are alerted that if they are admitted into a shared room that does not currently have a roommate, there is a possibility of an admission coming in during the night. The parent is asked if they wanted to be woken up at night if a patient is admitted into the room. The nurse admitting a new patient in the middle of the night to a shared room uses a quiet voice when speaking and encourages the patient and parent to do the same. Quiet time is discussed upon admission and is an ongoing conversation throughout the stay. Cell phone use and TV volume are monitored by the staff and they gently remind families to be courteous of their roommates. Since staff conversations outside the room was also an area needing improvement, according to the HCAPS scores, all staff members were made to feel empowered to alert others when the noise level became too loud. As a quiet way to alert staff to decrease the noise level, the lights are turned on and off to make everyone aware that it was getting too loud. Conversations outside and inside the patient’s rooms were minimized during the nursing handoff at the shift change.

Lastly, since it was previously noted that the housekeeping staff cleaning the floors at 6 am caused a significant spike in noise level during the designated quite time, through interprofessional collaboration, the team was able to change the time of the Zamboni cleaning to after 7:30 am. Cleaning the floors later prevented a disruption within the quiet time hours.

Results

Pre-data noted that 37% of patients reported on the HCAHPS survey that the noise around their child’s room was quiet at night, and they were able to have a restful night of sleep. Post-implementation during the 1Q19 Press Ganey survey question regarding the patient’s room’s perceived noise level at night increased to 52%, representing a 36% overall improvement. 2Q19 and 3Q19 showed sustained improvement at 50% and 49% respectfully.

The staff also noticed a change in Med 3 since Quiet at Night was implemented. One Nursing Assistant said he noticed a decrease in direct patient complaints when it came to noise at night.

Next Steps

As a result of the Quiet at Night program’s success on the Med 3 unit, next steps include expanding the project to the additional units of this hospital. To maintain sustainability, Quiet at Night monthly meetings have continued. These meetings now include representatives from the additional units to provide support and guidance as they implement the new process on to their units. Lastly, periodic spot checks performed with the mechanical ear to evaluate the noise level are planned to aid in the continued awareness and success of this initiative.

Conclusion

Sleep within the hospital setting is vital for the promotion of healing and wellness. This can prevent additional complications and prevent the increased length of stay for patients and families. This initiative’s impact is far-reaching in the improvements for patients, families, and the overall health of the staff.

References

Boehm, H., & Morast, S. (2009). Quiet time. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 109(11), 29-32.

Choiniere, D. B. (2010). The effects of hospital noise. Nursing administration quarterly, 34(4), 327-333.

Joseph, A., & Ulrich, R. (2007). Sound control for improved outcomes in healthcare settings—the Center for Health Design, 4, 2007.

Yarar, O., Temizsoy, E., & Günay, O. (2019). Noise pollution level in a pediatric hospital. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 16(9), 5107-5112.

Tania Wang BSN, RN, CPN Assistant Nurse Manager, Med. 3 Cohen Children Medical Center Laura Dunac MSN, RN, CPN Clinical Nurse, Med 3 Cohen Children’s Medical Center Camille Cipriano BSN, RN, CPN Assistant Nurse Manager, Med 3 Cohen Children’s Medical Center

from page 11

appropriately and frequently. Unfortunately, there is currently only one microtube that can be processed by the automated machine, and this tube cannot run every type of blood test. We are hopeful that additional tubes will be produced that will allow many other tests to be processed in the same efficient manner.

References

Maybohm, P., Richards, T., Isbister, J., Hofmann, A., Shander, A…Zacharowski, K. (2017). Patient blood management bundles facilitate implementation. Transfusion Medicine Reviews, 31, 62-71.

Steffen, K., Doctor, A., Hoerr, J., Gill, J., Markham, C… Spinella, P.C. (2017). Controlling phlebotomy volume diminishes PICU transfusion: Implementation process and impact. Pediatrics, 140(2), e1-e9.

World Health Organization. (2010). WHO guidelines on drawing blood: Best practices in phlebotomy. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/268790/ WHO-guidelines-on-drawing-blood-best-practices-in-phlebotomy-Eng.pdf?ua-1

Noelia MaGowan MSN, RN, CPNP, Nurse Educator

Cohen Children’s Medical Center Geraldine Shikora CLT, MS Ed., Educator Clinical Lab Long Island Jewish Medical Center

Zack Shapiro, RN-BC Assistant Nurse Manager Peds Emergency Department Cohen Children’s Medical Center

from page 25

Outcomes:

Pre-implementation data collected over three months showed the patient experience Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) score for overall Nursing communication domain at 90.7% and post-implementation over three months at 94.4%, representing a 4.4% increase. Next Steps:

First, the ABCDEF workgroup needs to find a reliable process for replicating and distributing the brochures and diaries in the PICU. The brochure is also being translated into Spanish to meet the needs of more patients and a survey is being developed to capture the impact on family participation in care, rounds, requesting family meetings, and advocating for patient safety. References:

Coats H. Nurses Reflections on the Benefits and Challenges from page 15

The success of Project BREATHE has been a multidisciplinary approach to asthma education. The addition of home care visits has shown to increase the adherence to the medication regimen, improve patient’s asthma control, and decrease readmissions and ED visits. To continue to build on the success of Project BREATHE going forward, we would like to maintain readmissions and ER visits at less than 10% for those who accepted a homecare visit. Also, we aim to incorporate additional follow-ups at three months and six months. Conclusion

Overall, homecare visits, combined with inpatient asthma education, provide a unique opportunity to empower the patient and family to manage asthma. The one-on-one instruction within the family’s own environment allows for a true partnership and personalized care. This leads to fewer asthma exacerbations and has the potential to break the cycle of recurrent hospital and emergency room visits across a child’s lifespan. References

Anderson, M. E., Zajac, L., Thanik, E., & Galvez, M. (2020). Home visits for pediatric asthma-A strategy for comprehensive asthma management through prevention and reduction of environmental asthma triggers in the home. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 100753. Bhaumik, U., Sommer, S. J., Giller-Leinwohl, J., Norris, K., Tsopelas, L., Nethersole, S., & Woods, E. R. (2017). Boston children’s hospital community asthma initiative: Five-year cost analyses of a home visiting program. Journal of Asthma, 54(2), 134-142.

Bracken, M., Fleming, L., Hall, P., Van Stiphout, N., Bossley, C., Biggart, E., ... & Bush, A. (2009). The importance of nurse-led home visits in the assessment of children with problematic asthma. Archives of disease in childhood, 94(10), of Implementing Family-Centered Care in Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Am J Crit Care 2018; 27(1): 52-58.

Davidson et al. Family response to critical Illness: Post-Intensive Care Syndrome-family. Crit Care Med 2012.

Davidson et al. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 103-128. https://www.sccm.org/ICUliberaton

Mary Schafer MSN, RN, CCRN, PNP Clinical Nurses, PICU

Improving Outcomes For Children with Asthma

Cohen Children’s Medical Center 780-784.

Campbell, J. D., Brooks, M., Hosokawa, P., Robinson, J., Song, L., & Krieger, J. (2015). Community health worker home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2366-2372.

Fernandes, J. C., Biskupiak, W. W., Brokaw, S. M., Carpenedo, D., Loveland, K. M., Tysk, S., & Vogl, S. (2019). Outcomes of the Montana Asthma Home Visiting Program: A home-based asthma education program. Journal of Asthma, 56(1), 104-110.

Marshall, E. T., Guo, J., Flood, E., Sandel, M. T., Sadof, M. D., & Zotter, J. M. (2020). Peer Reviewed: Home Visits for Children with Asthma Reduce Medicaid Costs. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17.

National Center for Health Services Research. (2011). Health, United States. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Health Resources Administration, National Center for Health

Statistics. Shari Bernstein MSN, RN, AE-C, Asthma Educator, Cohen Children’s Medical Center

Judith Jeanty MSN, RN, AE-C, Asthma Educator, Cohen Children’s Medical Center

from page 24

disheartening and it made you start to wonder if we were going to save any of them. I had to consistently remind myself and others that the majority of persons with a positive COVID swab didn’t end up in the ICU, but it was hard to remember.

Going over to the adult side in the middle of a pandemic wasn’t something I ever thought I would experience. There were beautiful and horrifying moments. Every day, I went home and would decontaminate as best I could. Clean my shoes, badge, bag, face shield, pens. The next step would be a sizzling hot shower. Decompression was always very important to me post-shift, which could mean an array of activities including yoga, cooking, watching Schitt’s Creek over and over again, or even just laying directly in bed. One night I called an emergency Zoom meeting with my girlfriends because I had missed contact with people who weren’t in the hospital. Days off were also very important. I did pick up extra shifts, but I had learned fast that I needed my days off. My mother and I started a tradition of doing a FaceTime workout on my off days at 2 pm. It was a way to stay in contact, and it was important for my sanity.

This time in my life will never be forgotten. It was a time when not only my skill as a nurse was tested, but my humanism and resilience were tested as well. A quote that I love from poet and samurai Mizuta Masahide goes like this, “My barn having burned down, I can now see the moon.” I find this incredibly fitting when reflecting on the two months I spent in the adult COVID ICUs. A great percentage of my memories are of a very scary, uncertain time, but if I look very closely, I can see the smallest of a silver lining.

Maryann L. Peterson BSN, RN, CPN, C-NPT Clinical Nurse Pediatric Transport Team Cohen Children’s Medical Center