37 minute read

CHAPTER

Erythema multiforme 136 Toxic epidermal necrolysis 137

Pemphigus vulgaris 137 Bullous pemphigoid 137 Systemic lupus erythematosus 139 Idiopathic ulcerative disease 139

Advertisement

Indolent ulcers 139 Skin fragility syndrome 139

CHAPTER 12

Clinical approach to feline alopecia

General consideration 143 Distribution and localization of alopecia 145 Diagnostic approach 146 Mechanisms for alopecia 148

CHAPTER 13

Clinical approach to feline otitis

General consideration 153 Factors involved in otitis externa 153

Otitis externa vs. otitis media 154 Diagnostic approach to otitis externa 155 Approach to otitis media 160 Approach to Pseudomonas cases 162

A note about ear cleaners 163

CHAPTER 14

Clinical approach to feline facial dermatitis

General consideration 165

Allergies 165 Parasites 169 Immunomediated diseases 171

Nodular diseases 174 Viral diseases 175 Polychondritis 175 Diseases of the planum nasale 175

CHAPTER 15

Clinical approach to feline pododermatitis and nail diseases

General consideration 177

Terminology 177 Differential diagnosis 178

Infectious diseases 178 Allergic disease 182 Plasma cell pododermatitis 182

Other conditions 182

Clinical approach to feline crusting dermatitis

General considerations

Crusts and scales are common secondary skin lesions with multiple causes in dermatology, coming from many underlying diseases. Since crusts and scales are non-specific, it is crucial for clinicians to identify, whenever possible, the primary lesions, thus providing a clue about the underlying primary disease.

The clinical appearance of crusts and scales is frequently described under the term “seborrhea”. This is not an actual diagnosis but a mere description of a clinical appearance. Seborrhea can be described as greasy or dry. It should be kept in mind that, in clinical practice, very few seborrhea cases are actually due to a primary keratinization disorder (also referred to as “primary seborrhea”). The vast majority of cases are secondary and the cause should be identified as there is no treatment that “fixes them all”. A large variety of mechanisms can lead to the formation of crusts and scales. In this chapter, details about the specific diseases and disorders will be discussed, explaining how to sort out the list of differential diagnoses developing a step-by-step logical and sequential approach to crusting dermatitis (Fig. 8.1).

Skin scraping Cytology Fungal culture

YES

Treat based on ndings and reassess

Consider treating to rule out possibility using a broad spectrum product

Treat based on assessment of cytological ndings in combination with clinical signs and reassess

If negative for secondary infection: If parasites and dermatophytes have been ruled out, consider biopsy If acantholytic cells are found on cytology without bacteria, biopsy to con rm pemphigus foliaceous

NO NO

Bacteria or yeast

Consider other differential diagnoses on the list based on distribution of signs

Treat for dermatophytosis See chapter 6 for more details

Figure 8.1 Flowchart summarizing the diagnostic approach to crusting dermatitis in cats.

YES

Etiologies of crusting dermatitis

Crusts can be the result of pustular disorders. Pustules are primary but very transient lesions, and rupture easily leaving epidermal collarettes and crusts as secondary lesions.

Pustules are frequently the result of the maturation of a papule. Thus, the way to approach a case could be considering differential diagnoses for papular diseases. For this purpose, it is important to note that papules may be centered around a follicle or not.

BACTERIA AND PARASITES

Follicular causes of papules and, therefore, pustules, include Staphylococcus spp., Demodex cati and dermatophytes. All these disorders are oriented around follicles and have been reported as a cause of folliculitis in cats. Thus, in the initial approach to either rule in or rule out these follicular disorders, it is useful to perform a deep skin scraping to detect D. cati, a fungal culture combined with a Wood’s lamp exam to address the differential diagnosis of dermatophytes, and a cytology of either an intact pustule or underneath an existing crust, hoping to find some moist areas that can be suitable for an impression cytology. A cytology is aimed at detecting bacteria and obtaining information about the type of inflammatory infiltrate and the possible presence of acantholytic cells. In the event that there are no moist lesions, a tape can also be used to collect crusts and scales. This type of cytology can be more difficult to read at times, as the material may be too thick to allow easy visualization. It should be kept in mind that cocci may be extracellular if neutrophils are degenerated, and this is highlighted by the presence of “nuclear streaming”, which are strings of blueish material collected during the swabbing or the smearing of the slide. If no bacteria are identified, this may not rule out the presence of infection, as bacteria may stay inside the follicles and may not be visible on a surface cytology. As already mentioned several times in previous chapters, secondary infections are extremely common and should always be considered when approaching dermatological cases. Any form of inflammation and self-trauma increases the risk of bacterial infections.

When considering other differential diagnoses, we should remind ourselves that papules (and pustules) are not always centered around hair follicles. Those parasitic diseases in which a parasite actually bites the skin can lead to the development of papules, then pustules and then crusts.

Some examples are mites like Notoedres spp., insects like fleas or even bites from fire ants and mosquitoes. Another parasitic disease that can cause scaling (typically dorsal) is Cheyletiella spp. (also called “walking dandruff”). Although this parasite is becoming less common due to the prevalent use of flea products, this is a possible differential diagnosis for scaling. Mosquito bites are located preferentially on the nose, tip of the ears and paws. The bite in allergic patients leads to a severe accumulation of eosinophils. Once these cells degranulate, severe tissue injury occurs, leading to necrosis and collagen degeneration. Lesions are both pruritic and can be painful and unfold in a short time. The classic history is the one of an outdoor cat that is not being treated with any repellent. Interestingly, plants like catnip are repellent to mosquitoes and can be used as a strategy to limit mosquito bites for cats that would not make suitable indoor pets.

ALLERGIC DISEASES

Some allergic diseases can manifest with a papular eruption which then leaves crusts; these papules are not centered around the follicle. This is the case of a contact dermatitis, which can be allergic or irritant in nature. Allergic cases are pruritic, while irritant cases are more painful and they typically start with a blister rather than a papule. Regardless, if lesions are found on an area where the owner is applying a certain topical product, this differential diagnosis should be considered, and the area must be washed with a mild shampoo (e.g., oatmeal and ceramide based shampoo), apply some topical steroids and stop the application of the previously used product. It is important to remember that many topical products may use propylene glycol as a vehicle. This ingredient tends to be allergenic for many animals. If the patient has become sensitized to that ingredient, careful selection to identify a glycole propylene-free product is needed.

Flea allergy and food allergy can also manifest with papules and crusts. For example, miliary dermatitis

is a clinical presentation frequently associated with allergies and presenting with dorsal crusting. With environmental allergy, crusts are more often the result of self-trauma rather than the result of a primary papular/pustular eruption, although much still needs to be learned about “atopic syndrome” in cats.

AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES

Another possibility of having pustules that are not centered around the hair follicle is the case of autoimmune diseases like pemphigus foliaceous. In this case, antibodies against desmogleins (proteins responsible for intercellular connections in the epidermis) are attacked by autoantibodies. As a result, keratinocytes prematurely detach from each other (also known as acantholytic cells), inflammatory cells like neutrophils and eosinophils are recruited in the epidermis, forming a subcorneal pustule. These lesions are fragile and very transient: they break very easily and are replaced by crusts.

VIRAL DISEASES

Blistering diseases also can lead to crusts. Viral diseases like herpes are an important consideration for cats with crusting dermatitis on their face and around their eyes (Figs. 8.2-8.3). Stomatitis is frequently present. Herpes dermatitis can be a major diagnostic dilemma, as allergic or autoimmune diseases can look very similar with oral lesions and crusts around the eyes, mouth and bridge of the nose. As the latter require immunemodulation/suppression with glucocorticoids or cyclosporine (which would be contraindicated in the case of herpes), it is very important to make the correct diagnosis. Frequently, this requires a viral testing or a skin biopsy that can help to detect the pathognomonic changes. Herpes viral inclusions, as well as changes like ballooning degeneration, are diagnostic while in the case of allergic diseases, eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates with collagen degeneration would be very common. In the case of pemphigus, acantholytic cells lay either subcorneally in a pustule or simply in layers of crusts that have developed over time.

BULLOUS DISEASES AND VASCULITIS

Another mechanism to develop crusts are either bullous diseases or diseases affecting the wall of blood vessels like in the case of vasculitis. In bullous diseases, which are typically autoimmune in origin, the bulla is the primary lesion; it is very transient and is quickly replaced by a crust. Some examples of this are diseases like systemic lupus, pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid. All these diseases are very aggressive clinically and are associated with systemic illness. Patients are

Figure 8.2 Erosive/ulcerative dermatitis around the eye and side of the face in a cat with herpes-induced dermatitis. Many patients have ocular disease as well as cutaneous disease (UF case material).

Figure 8.3 Another patient with herpes dermatitis. This cat has conjunctivitis, periocular dermatitis and stomatitis, and associated drooling.

Figure 8.4 Vasculitis in a Persian cat. This patient had necrotic/ulcerative lesions on the tip of the ears and ulcerative lesions on the side of his face. The triggering cause of the vasculitis was unknown in this patient.

lethargic, frequently drooling as lesions are commonly located in the oral cavity. Anorexia, fever and malaise are common signs. Patients with lupus may have joint problems and lameness can be a manifestation. A frequent place where these diseases start is the oral cavity. Signs can become generalized quickly in some patients. It is common to find lesions on the face, around the eyes, and frictional areas. Nails are frequently sloughed and animals are reluctant to walk and eat.

In those diseases affecting the blood vessel walls like vasculitis, necrotic lesions (and therefore crusts) are common at the extremities, like the tip of the ears, tip

of the tail and the center of each footpad (Fig. 8.4). Vasculitis is a type-III hypersensitivity, an antigen/ antibody immune complex-driven disease. These complexes are likely to affect small vessels and extremities, although they can also affect larger vessels. Thus, it is important for the clinician to note the distribution of lesions and the presence of concurrent signs.

IDIOPATHIC ULCERATIVE DERMATITIS

Sometimes crusting lesions can be found over a previous injection site. Many of these cases have developed vasculitis, which then lead to a vascular insult manifested as alopecia or crusted areas where the blood flow to the specific area is compromised. One particular disease, called idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis, has been speculated to be associated with injection reactions (Fig. 8.5). These cats develop recalcitrant ulcerative/crusting lesions on the back of the neck and in between the shoulder blades. The focal nature and location of these lesions are a strong suggestion of the possible etiology of this condition.

Figure 8.5 Ulcerative dermatitis. In this case, the trigger was not identified and the patient showed partial improvement with glucocorticoids and treatment of the secondary infection but never healed completely and always relapsed any time the treatment was discontinued.

METABOLIC CAUSES

Crusts can also be the effect of a direct insult like a spider bite, and scaling can be result of a metabolic problem like diabetes (Fig. 8.6).

This is not a common differential in cats but should be considered in geriatric patients with concurrent illnesses. NEOPLASIA

Scaling and crusting may also be the result of accumulation of neoplastic cells like the case of cutaneous lymphoma (also known as mycosis fungoides). This disease has many different manifestations but one is erythroderma, intense pruritus, particularly in older cats and even cats that have never had a skin disease before nor a prior history of allergic disease. Diffuse silvery scaling and crusting is common (Figs. 8.7-8.8), together with thinning of the hair coat. These patients

Figure 8.6 Scaling dermatitis and hair loss in a cat with diabetes. In these patients it is important to rule out D. cati due the immunosuppressive effects of diabetes, and to do a cytology for Malassezia, which can flourish under these conditions.

Figure 8.7 Crusting dermatitis on the head of a cat diagnosed with mycosis fungoides. This patient was severely pruritic and also had a secondary bacterial infection. Figure 8.8 Same patient after clearing the infection. Note the intense erythema and some crusting that persisted and was linked to the underlying mycosis fungoides. Pruritus remained intense.

typically show weight loss and are generally unwell although early on in their disease they may seem very similar to an allergic patient posing a clinical challenge. Many may be considered potential food allergic cats as food hypersensitivity may start at any age and may be associated with pruritus that may not respond to glucocorticoids. It is suggested to biopsy older pruritic crusty cats, minimally to rule out the possibility of cutaneous lymphoma before embarking into a lengthy food trial (8+ weeks) or other investigations for allergies.

Thus, crusting and scaling in older cats should prompt the consideration of a possible neoplastic or metabolic condition. Indeed, scaling and alopecia may be a manifestation of an internal disease. This is the case of thymoma-associated dermatitis (Fig. 8.9). This is a syndrome in which scaling and hypotrichosis are associated with the presence of a thymoma. Diagnosis is made by skin biopsy and a thoracic radiograph showing a mediastinic mass. MALASSEZIA OVERGROWTH

Metabolic, endocrine and allergic diseases are associated with the altered production of lipids and become predisposing causes of Malassezia overgrowth. This disorder manifests with brown crusting and scaling frequently around the commissure of the mouth, nails, and face. It is frequently associated with pruritus and a history of a lack of responsiveness to standard antibiotic courses. Cytology again is a very important part of the evaluation of any dermatology cases and can provide a diagnosis in this case. Although there is no magic number of yeasts necessary to make a diagnosis of Malassezia dermatitis, the presence of yeasts on cytology in combination with the above described clinical signs is highly suggestive of this secondary infection. It is crucial to remember that Malassezia is a secondary cause in the vast majority of cases; thus, a diagnosis of Malassezia should prompt the clinician in the search of the underlying disease.

PRIMARY KERATINIZATION ALTERATION

Crusting can also be the result of a primary disease of keratinization. In this case, crusting and seborrhea are evident early on in life. Kittens are known for having greasy skin at a very young age. Owners complain about the feel of their coat and the fact that they appear “dirty and greasy” even with frequent bathing. These cats are very prone to the development of secondary infections. Initially they are not pruritic but once they develop bacterial and yeast infections, they can become very pruritic. Typically, the course shows temporary improvement with the treatment of the secondary infections, but infections typically recur as soon as the treatment is discontinued. This is because the skin is not normal and it is very prone to repeated overcolonization by bacteria and yeasts. The ears are also affected and excessive wax production and ceruminous otitis are also common manifestations. A slang term of a presentation of primary seborrhea is “dirty face syndrome” in which kittens have crusting and greasy skin around their eyes, mouth and ears. His disease is genetically inherited and cannot really be cured. A faster mitotic rate and abnormal composition and mount of skin lipids are believed to be the result of primary seborrhea. His disease can be managed symptomatically by dealing with secondary recurrent infections and applying topical therapy with keratolytic agents like sulfur and salicylic acid to remove the crusts, scales and cut down on the number of bacteria and yeasts. It is important to remember that ingredients like tar (used as keratolytic and keratoplastic agent in dogs) and selenium disulfide, used to kill yeasts in dogs and people are toxic to cats and should never be used in this species. Sulfur can be used in cats and can be used both as a shampoo or as a dip. The dip can be used also as a topical therapy to address dermatophytes and some mites (e.g., notoedric mange). Another option to degrease the skin and remove crusts is the use of benzoyl peroxide. This is antimicrobial and has the ability to both help with secondary bacterial infections as well degreasing the skin.

Distribution of crusting dermatitis lesions

The distribution of some of these diseases can certainly overlap. For example, Notoedres spp., dermatophytes, Demodex spp., and pemphigus all frequently affect the face and ears. Yet, a trained eye can detect subtle changes that can help rank these differential diagnoses. For example, Notoedres spp. prefers the margins of the ears (Fig. 8.10) and is associated with great pruritus. Pemphigus usually affects the concave surface of the pinnae (Figs. 8.11-8.12), the chin (Fig. 8.13), the bridge of the nose (Figs. 8.14-8.15), the perinipple area (Figs. 8.168.17) and the nail folds (Figs. 8.18-8.20). So, a clinician should know which sites to check to help in the ranking of these diseases.

Figure 8.10 Crusting on the margin of the pinnae of a cat with Notoedres spp. Note the crusted papules on the pinnae. Notoedres is a superficial mite and the papules are the result of the mite burrowing in the skin. These papules are not oriented around the hair follicles. Superficial skin scrapings are indicated to diagnose this highly pruritic disease.

Figure 8.11 Papules and pustules in the concave pinna of a cat with pemphigus foliaceous. The pustules are large and span multiple follicles. They are transient and quickly replaced by yellow crusts.

Figure 8.12 Large yellow crusts on the concave surface of the pinna of a cat with pemphigus foliaceus.

Figure 8.13 Large crusts on the chin of a cat with pemphigus foliaceous. This patient had been originally misdiagnosed as a “bad case of chin acne”. Cytology was useful to show a large number of acantholytic cells.

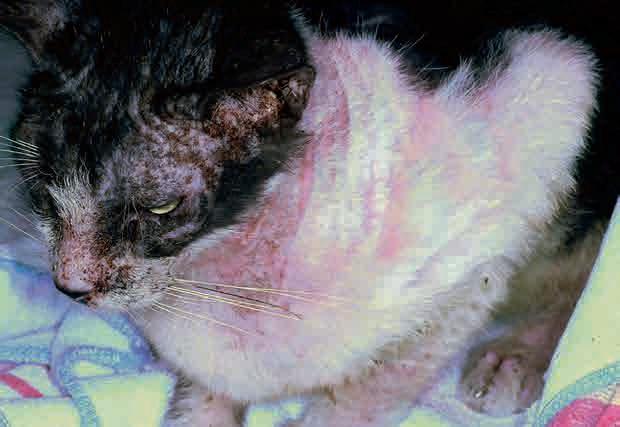

Figure 8.14 Patient with systemic severe pemphigus showing depression and crusts on the nose and preauricularly.

Figure 8.15 Same patient of Fig. 8.14 after starting therapy, showing a decrease of crusting on the nose.

Figure 8.16 Pemphigus patient showing intense erythema and perinipple crusting.

Figure 8.17 Pemphigus patient showing epidermal collarettes in the perinipple area. This area is a common site for pemphigus in cats. Once the pustules break, epidermal collarettes can be commonly found. Figure 8.18 Nail bed area filled with dry exudate in a cat with pemphigus foliaceus. The nail bed area is commonly affected. The material can be used for cytology to demonstrate neutrophils and acantholytic cells.

Figure 8.20 Severe case of paronychia and crusting involving the whole foot and footpad in a patient with pemphigus foliaceous. This patient was unable/unwilling to walk and was systemically ill as a consequence of the fare of pemphigus.

Clinical signs

Pemphigus is not typically considered a pruritic disease, yet some cases can be pruritic. It can be linked to secondary infections as well as the fact that some patients have a strong eosinophilic component. Pemphigus patients are typically middle-aged cats that many times also waxe and wane and show a decreased appetite and lethargy. Not every patient shows all these signs, but it should be noted whether there are any other systemic manifestations.

Crusts can be the result of pruritic diseases that simply lead to excoriations. If the history points towards the presence of pruritus, these cases need to be worked out for this cause. Many allergic cats can present with crusting on their faces (Fig. 8.21), sides and periocularly due to the self-trauma or actual mosquito bites (Fig. 8.22). These crusts lack the honey colored appearance of the crusts of autoimmune diseases and the characteristic crusting of the margin of the pinnae as seen in notoedric cats.

Diagnosis of crusting dermatitis

In terms of addressing the possibility of parasitic diseases, when approaching a case of crusting dermatitis, wide, superficial scrapings for Notoedres spp. must also be considered, and not just deep skin scrapings for Demodex cati. It is important to remember that Notoedres spp. mites may not be present in all scrapings, and that empirical treatments may be necessary to rule out this disease when suspected. Drugs suitable for that approach are topical flurananer, which can address D. cati, D. gattoi and Notoedres spp.) or selamectin, which would address Notoedres spp. and D. gattoi. Another option to address Notoedres spp. and D. gattoi is the use of lime sulfur dips. This is more labor intensive but has the added benefit of being a strong antipruritic agent, as well as an effective treatment for a potential dermatophytosis. This is a choice that some clinicians may consider while waiting for fungal culture results, or when dealing with patients with intense pruritus. Based on the availability of products and patient considerations, a clinician can pick and choose which treatment to recommend.

Figure 8.21 Self-inflicted excoriations and crusting in a flea allergic cat.

Figure 8.22 Primary nodular eruption in a cat with mosquito hypersensitivity. Lesions are primary and induced by the bite. The eosinophilic accumulation in the skin after the bite leads to damage of the skin and formation of crusts. Lesions can be pruritic and even painful. Skin damage develops even when trauma is prevented by using an e-collar.

When a cytology is done from the nail bed of these patients it is common to find, besides inflammatory cells and some cocci, large round blue epithelial cells with a nucleus. These are acantholytic cells (Fig. 8.23). Since epithelial cells detach before complete keratinization, they do not present as polyhedral shaped squames with no nucleus (Fig. 8.24). Instead, they are smaller, still have a nucleus, and are round-shaped. Although acantholytic cells can be formed in other diseases besides pemphigus, this finding should be noted and pemphigus must be considered as a possible differential diagnosis. Such differential should be pursued with a skin biopsy. The reason why other disorders can also cause acantolytic cells is that any time there is a severe influx of neutrophils in the epidermis, and these cells release their proteolytic enzymes in the dermis, desmogleins can be damaged and acantholytic cells can be generated in ways that are not autoimmune diseases but simply a severe inflammatory disease. This can be, for example, the case of a severe contact dermatitis or a severe dermatophytosis.

Figure 8.23 Cytology from the patient in Fig. 8.20 showing acantholytic cells (large circular blue cells with a nucleus, derived from premature separation of keratinocytes in the epidermis). Figure 8.24 Cytology showing neutrophils and clusters of acantholytic cells (indicated by red arrows) and a couple of desquamated keratinocytes (no nucleus, polyhedral shape, indicated by black arrows). Desquamated keratinocytes are common in skin cytology, while acantholytic cells point towards some form of disruption of the epidermis, either due to an autoimmune disease like pemphigus or some severe inflammatory response in the epidermis which leads to premature separation of keratinocytes before they have undergone the process of keratinization which would include the loss of nucleus and the change of shape from round to polyhedral.

Treatment of crusting dermatitis

Milder options for dry seborrhea include the use of emollients and moisturizers like ceramides and phytosphingosine, a precursor of ceramides. Some of these products are combined with antimicrobial agents like chlorhexidine. Typically, shampoos are more difficult to use in cats compared to leave-on-type conditioners. Sprays are also difficult to apply and may need

to be applied on a gauze before being applied to the animal. Another good option is also the application of sphingolipid emulsions or essential fatty acid-type preparations in the form of a spot-on. These products are applied between the shoulder blades and diffuse in the surrounding areas providing essential fatty acids which improve the coat condition and potentially the patients’ skin barrier function. More knowledge in this regard has been obtained in canine patients compared to feline patients. Nevertheless, some clinicians choose this option as it is considered safe and moderately effective for cases of dry skin.

Pemphigus foliaceous

Pemphigus foliaceous is the most common cutaneous autoimmune disease in cats. It can occur for a variety of reasons. In some cases it is possible to identify a triggering antigen against which the immune system is mounting a response ranging from vaccines to drugs and even some flea products.

This immune response cross reacts with desmogleins in the upper epidermis and the antibody, which were intended for another allergen, attacks the desmogleins as an innocent bystander. This is an IgG-mediated response. It is a type-II hypersensitivity, a cytotoxic reaction that triggers the accumulation of inflammatory cells like neutrophils, and even eosinophils. The result is the breakage of the connection between epidermal keratinocytes and the formation of pustules. In some cases it is possible to identify the trigger. This is very important to do in very young animals that otherwise would not be in the “right age” for autoimmune diseases. It is important to question the vaccination history, and any drug or supplement that was given to the animal. This is because the majority of the so-called “idiopathic” autoimmune cases (aka “cases in which a triggering cause cannot be identified”) are typically middle-aged. In those cases, it is almost accepted that the immune system is attacking itself for no obvious cause.

It is important to remember that, in order to build an immune response to an antigen, the patient could have been exposed to it without any problems for a while. So, rather than ruling out vaccines, flea products or drugs that have been used in the past without any problem, anything should be carefully considered. Particular attention must be paid to treatments that were administered in the 4-6 weeks prior to the development of signs. Some have a very good prognosis once the “aberrant” immune response is suppressed and no additional exposure to the offending allergen occurs. Some cases, however, are self-perpetuating and can continue to develop lesions even when the offending allergen is removed and require long-term immune suppression, just like an idiopathic case would require.

In older patients, triggers like neoplasia must be considered as they are “too old” for the idiopathic form for the disease. In these cases the immune system is also reacting to an antigen related to the tumor, which happens to cross-react with an epidermal epitope leading to an autoimmune response. Failure to identify the triggering cause or dealing with a triggering cause that cannot be removed or avoided, makes treatment particularly challenging and worsens the prognosis. Having said this, the author has seen pemphigus in patients of all ages.

Some cases are patients with a previous history of allergies, and then the owners report a “change in signs”. These cases may be more subtle to diagnose as they have had skin disease all their lives but the disease changes from being well controlled with anti-inflammatory doses of glucocorticoids or cyclosporine to being more recalcitrant and being associated with crusting and malaise. A drug eruption should always be considered whether in the form of pemphigus or erythema multiforme. It is also important to consider that chronic skin trauma can actually, sometimes, expose the immune system to antigens that were otherwise protected. This is one speculation of why allergic patients may later on in life develop autoimmune skin diseases. This is proposed to be a result of chronic trauma and the formation of autoantibodies.

Generally speaking, a predisposition towards females is reported for autoimmune diseases. In terms of clinical manifestations of pemphigus, they vary greatly. Some patients have localized and mild disease for a long time. They are sometimes misdiagnosed as cases of chin acne that does not improve with standard treatment. In these cases, lesions are papules, pustules and crusts on the chin. Frequently, the disease eventually unfolds into a pustular eruption on the pinnae and bridge of the nose as well as periocularly. This pattern is sometimes described as a “butterfly” pattern. The lesions are pustules, frequently large and spanning multiple follicles, intermixed with honey-colored

crusts. Sometimes with histopathology it is possible to see the various layers of pustules and acantholytic cells and this is the reflection that this disease has a classic course of waxing and waning flares. During the flares, the patient does not feel well; it stops eating, and may run a fever. This is typically associated or shortly followed by a new eruption of pustular lesions. With each “wave” the disease tends to become worse, more aggressive and more generalized. If the patient has been exposed on and off to suboptimal doses of glucocorticoids, the disease also becomes progressively more resistant to glucocorticoids. The typical scenario is that the first few rounds of steroids provided some improvement although temporary and not complete and eventually stop helping. This is a very important reason for which it is crucial to make a timely diagnosis and treat these patients with the appropriate dose of glucocorticoids as well as other steroid sparing agents. When we think of diseases that become resistant to treatment we tend to think of bacterial infections. Yet, autoimmune diseases can do this as well, creating a major management challenge.

Sometimes, what happens in real life is that either owners or veterinarians are hesitant to biopsy, so clinicians empirically prescribe some glucocorticoids. As they are not sure about the diagnosis, typically anti-inflammatory doses or low immune-suppressive doses are prescribed for a short period. Glucocorticoids are hardly ever associated with a steroid sparing agent. Then, as soon as the tapering schedule of the glucocorticoid is done, lesions come back with vengeance. At this point, higher doses are needed or a different glucocorticoid is necessary typically moving from milder and safer choices to more long lasting powerful agents, with more potential for adverse effects.

So, when dealing with a case with a history of recurrent pustular/crusting eruption affecting the face, it is important to consider pemphigus foliaceous on the list of differential diagnoses and consider a skin biopsy than to attempt glucocorticoid therapy without having a diagnosis. Other areas that are commonly affected are the nail folds, the perinipple area and the footpads. The nails themselves are typically not affected. This is important because if they are, dermatophytosis should become a priority in the rule outs. Affected patients are reluctant to walk and lethargic. One area that is not affected in pemphigus foliaceous patients is the oral cavity. It should be noted that pemphigus foliaceous is a cutaneous disease and not a disease of the mucous membranes like other autoimmune diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris or bullous pemphigoid.

As mentioned before, besides skin scraping (both superficial and deep) and fungal culture, cytology is an integral component of the basic dermatology workup. The detection of acantholytic cells is easier in those patients that are actively flaring and have not been recently exposed to glucocorticoids. In order to confirm the diagnosis of pemphigus it is strongly recommended to follow up with a skin biopsy. The best lesion to biopsy is a pustule or an area with crusts. The worst area to biopsy is an ulcerated area as the disease is in the epidermis.

It is beneficial to clip the areas surrounding the affected regions and search for new, fresh lesions. Sometimes, the less obvious and severe lesions are the best area to obtain an answer. Care should be taken not to damage any lesion when doing the biopsy. There should be no scrubbing or prepping of the area as it is crucial to preserve the pustules or the crusts. If no active lesions are present it is acceptable to submit crusts to be processed for histopathology.

A regular histopathology is sufficient and it is not customary to ask for immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry. The pustules typically span multiple follicles and are filled with neutrophils, eosinophils and acantholytic cells. The presence of bacteria can sometimes make the diagnosis of pemphigus a little more difficult and this is why, if possible, it is best to treat infections before the biopsy. The concurrent use of glucocorticoids also interferes with the ability to make a diagnosis and that is why it is important to refrain from starting any treatment before the biopsy, if at all possible.

In order to speed up ruling out dermatophytes, some clinicians may ask for special stains for dermatophytes if there is evidence of folliculitis as typically the histopathology report is available in a shorter time than the time required for dermatophytes to grow and for microbiology labs to provide final fungal culture results back.

Once the diagnosis of pemphigus is confirmed through histopathology, immunosuppressive therapy is initiated. This involves a combination of glucocorticoids and a steroid sparing agent. Many of these cases are also placed on a systemic antibiotic both because they may already have an infection and also to minimize future infections. In the author’s experience, very few cases can be managed just with the use of

glucocorticoids and a vast majority require a steroid sparing agent to allow sufficient tapering of the glucocorticoids and minimize the severity of the adverse effects. The vast majority of idiopathic cases require treatment for life, and the ones where there is a concurrent allergy tend to have flares of their pemphigus during their allergy season. Importantly, any form of stress, emotional or due to other illnesses, can lead to a flare of the autoimmune disease requiring increases of the medications necessary to control the pemphigus. The treatment is typically designed as composed by an “induction period” of 10-14 days followed by a “maintenance period”. In the induction period the remission of the disease is largely dependent on the use of glucocorticoids due to their strong ability to suppress inflammation. In the more chronic period, the remission is maintained by the steroid sparing agent. The steroid sparing agent typically has a lag phase of several weeks (2-6 weeks depending on the agent used). During this period of time adverse effects can already occur but minimal effect in the control of pemphigus exists. This is why the tapering of the glucocorticoids is done in a way to allow sufficient time for the steroid sparing agent to kick in.

In terms of glucocorticoids, a common starting medication is prednisolone. For those cats with excessive polyuria and polydipsia when using prednisolone, methylprednisolone can be used. A common starting immunosuppressive dose for prednisolone is 3.3-4.4 mg/kg orally twice daily. If methylprednisolone is used 1.5-3 mg/kg twice daily can be a good induction. Other options for glucocorticoids can be oral dexamethasone and triamcinolone. These are more powerful and longer lasting glucocorticoids that are typically only used when prednisolone or methylprednisolone are not good options. This is usually the result of developed resistance of the disease. Dexamethasone (induction dose of 0.2-0.4 mg/kg twice daily) and triamcinolone (induction dose of 0.4-0.8 mg/kg twice daily) can be used instead, but they induce adverse effects more quickly ranging from diabetes to increased liver enzymes, from cutaneous atrophy, skin fragility, propensity to infections (both cutaneous and urinary). The least desirable choice for glucocorticoids when managing pemphigus is the use of injectable long lasting preparations like DepoMedrol. These preparations are not amenable to the concept of alternating regimens for the sake of safety and to minimize adrenal suppression and it is very common to require more and frequent administration obtaining less and less control of the disease over time while accumulating more and more adverse effects.

For patients that cannot tolerate glucocorticoids altogether due to diabetes, for example, other options can be oral cyclosporine or, off-label oral oclacitinib. Cyclosporine is usually not an effective treatment for pemphigus as monotherapy but it can be used as adjunctive therapy either as a substitution of the glucocorticoids or as a steroid sparing agent. The dose of cyclosporine as adjunctive treatment is the same used for allergic skin diseases (7 mg/kg orally once daily or every other day during maintenance). Due to the metabolism of cyclosporine through cytochrome P450, it is important to consider other medications that are prescribed to the patient to minimize adverse drug interactions. Cyclosporine can induce adverse gastrointestinal effects in many patients like vomiting, diarrhea, nausea and decreased appetite. In many patients the dose can be decreased once the disease is in remission.

The use of oral oclacitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for use in dogs, has been adopted in some feline cases, both for the treatment of allergies and as adjunctive therapy for autoimmune diseases. Some cats may show positive response while others may not benefit from this approach. It appears that cats require larger doses than dogs, as it is the case for other medications so it is common to start with doses of 0.6 mg/kg twice daily for the first couple of weeks and then taper. The effect, if positive, is typically immediate. It is important to remember that oclacitinib is not anti-inflammatory per se like glucocorticoids are. The way this medication is designed is to block the signalling of multiple cytokines by blocking the JAK/STAT pathway. The actual synthesis of these cytokines is not directly decreased. This is one of the reasons for which worsening can be seen when decreasing or discontinuing this medication. This approach may be contraindicated in patients with a prior history of neoplasia.

The induction period is considered successful when no new lesions develop and the existing lesions appear drier, less erythematous and the patient is reported as feeling better and less lethargic. At that point, a slow progressive taper is done typically over a course of 8 weeks. The idea is to first decrease the dose on alternate days (the day in which the steroid sparing agent is given) while maintaining a full dose on the other day. The alternating dose approach having higher doses every other day rather than a lower equal dose every day is

more beneficial for the control of the disease and to minimize adrenal suppression too. Eventually, the goal is to taper to 25% of the total daily dose used for the induction and to give that dose every 48 hours. So, if a patient was placed in remission using a total daily dose of 12 mg of prednisolone daily, the final desired maintenance would be 3 mg every other day. Since the goal is to have glucocorticoids every other day, shorter acting glucocorticoids are preferred over longer acting ones.

As far as steroid sparing agents, a common choice is chlorambucil. This is an alkylating agent that has a profound effect on lymphocytes. It is used orally (0.10.2 mg/kg) either every 24 hours or every 48 hours. The author prefers to use this drug every other day from the very beginning of treatment to minimize adverse effects. An important adverse effect of this medication is bone marrow suppression besides increased liver enzymes. For this reason, complete blood work (complete cell blood count and chemistry panel) should be done at baseline as well as every 2 weeks for the first few months of therapy. It must be remembered that sometimes patients that appear to be well controlled and tolerating the medications for the first few months of therapy can, at any point in time, develop severe bone marrow suppression with chlorambucil. As a general consideration, every time there is a worsening of the disease, it is important to determine whether the worsening is actually due to a flare of pemphigus or due to another disease. Chronic immunosuppression makes these patients vulnerable to other diseases ranging from viral to fungal or bacterial. A particular dilemma is for cats that have herpes dermatitis or where that is a possible differential diagnosis. Some cats with herpes may not manifest with respiratory signs or ocular signs but just with skin lesions which follow the path of the trigeminal nerve and manifesting with erythema, swelling, crusting and ulcerations around the eyes and nose (Figs. 8.2 and 8.26).

It is important for clinicians to have a fresh approach when rechecking these patients rather than making an assumption that the worsening is due to pemphigus and increase the dose of glucocorticoids without further assessment. If the worsening is indeed pemphigus, this may be due to a temporary stressor (which will need to be identified and controlled as much as possible) and a mini-induction may be necessary. In the author’s experience the way this is accomplished is largely variable and dependent on the severity and characteristic of each individual patient. It could be a temporary and short-lived return to induction doses or a simple increase of the maintenance dose. In some milder patients it may be simply going back to daily steroids to later return to an alternate day regimen. Every patient is different and experience is crucial when addressing these situations. In general, it is more effective and in the long run minimizes the use of glucocorticoids, doing a few days of larger doses rather than a longer period of intermediate doses.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

■ In summary, crusting diseases in cats can be triggered in a variety of ways. ■ It is important for the clinician to identify primary lesions as much as possible and to eliminate secondary infections. By doing this, it will be possible to establish whether the pruritus (if present) is due to a secondary infection or is linked to the primary disease. ■ Diseases ranging from parasitic to allergic to autoimmune can cause crusting. The distribution of lesions can provide some

insight on how to rank the differential diagnoses. ■ As many diseases may look similar, skin scrapings, cytology and fungal cultures are a good practice in all cats with crusting dermatitis. ■ Empirical treatment for parasites may be needed to rule out this differential. Once infections and parasites are ruled out, a skin biopsy may be needed to diagnose other diseases like autoimmune or neoplastic.

Useful references

biziKova p, burroWS a. Feline pemphigus foliaceus: original case series and a comprehensive literature review. BMC Vet Res 2019;15(1):22. doi: 10.1186/ s12917-018-1739-y.

CoyNer K, tater K, riSHNiW m.

Feline pemphigus foliaceus in non-specialist veterinary practice: a retrospective analysis. J Small

Anim Pract 2018;59(9):553-559.

Hill pb, braiN p, ColliNS D,

fearNSiDe S, et al. Putative paraneoplastic pemphigus and myasthenia gravis in a cat with a lymphocytic thymoma. Vet

Dermatol 2013;24(6):646-649.

JorDaN tJm, affolter vK, outerbriDGe Ca, GooDale eC,

WHite SD. Clinicopathological findings and clinical outcomes in 49 cases of feline pemphigus foliaceus examined in Northern

California, USA (1987-2017).

Vet Dermatol 2019;30(3):209-e65. doi: 10.1111/vde.12731.

levy bJ, mamo lb, biziKova p.

Detection of circulating antikeratinocyte autoantibodies in feline pemphigus foliaceus.

Vet Dermatol 2020. doi: 10.1111/vde.12861.

maliK r, mCKellar SteWart K,

SouSa Ca, et al. Crusted scabies (sarcoptic mange) in four cats due to Sarcoptes scabiei infestation.

J Feline Med Surg 2006;8(5): 327-339.

orDeiX l, Galeotti f,

SCarampella f, et al. Malassezia spp. overgrowth in allergic cats.

Vet Dermatol 2007;18(5):316-323.

outerbriDGe Ca, affolter vK,

lyoNS la, et al. An unresponsive progressive pustular and crusting dermatitis with acantholysis in nine cats. Vet Dermatol 2018; 29(1):81-e33. prezioSi De. Feline pemphigus foliaceus. Vet Clin North Am Small

Anim Pract 2019;49(1):95-104. SimpSoN Dl, burtoN GG. Use of prednisolone as monotherapy in the treatment of feline pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 37 cats.

Vet Dermatol 2013;24(6):598-601.