5 minute read

Marketing the marginalised

Rowan Christina Driver - Music sub-editor

Is queerbaiting as harmful as it's made out to be?

Advertisement

Queerbaiting is a technique often used in media and marketing, a common practice of heavily implying non-heterosexual relationships without ever actually depicting them in the form of a bait-and-switch tactic.

The term itself is accusatory, but is queerbaiting necessarily always harmful?

The short answer is yes. Representation of nonheterosexual relationships remains few and far between in mainstream media. The few depictions of queer relationships we do get often fall victim to the “Bury Your Gays” trope, meaning at least one of the characters won’t make it to the end of the story – take the finale of Killing Eve, for example. Queer representation plays a crucial role in the shaping attitudes towards LGBTQ+ identities, and for many young people in particular the media they are exposed to forms a major source of their education on LGBTQ+ matters.

To represent these stories is to validate queer individuals. When such representation appears to be present, only to be stripped away to nothing, it perpetuates the stigma from which queerness seems unable to break free. Thus, denying queer individuals the opportunity to see themselves represented through media, which undercuts any and all validation they may feel by discouraging the normalisation of queer experiences. And, with those identifying as LGBTQ+ disproportionately affected by mental health issues, is it not crucial that we aim to destigmatise however we can? on, yet this is exactly what continues to happen. Queerbaiting is often reflective of widespread problematic attitudes towards queerness. To take an example – the most recent series of BBC hit Line of Duty featured longstanding character Kate Fleming (Vicky McClure) appearing to develop some level of romantic relationship with her new boss Joanne Davidson (Kelly MacDonald). A trickle of flirtatious exchanges, tentative physical touches, and a getaway car-chase later, both characters forget the other exists entirely explanation whatsoever for the subplot which began to unfold between them. A classic queerbait scenario, by all accounts.

Stonewall previously reported 52% of LGBT people had experienced depression in 2018, while the figure for young LGBT people (aged 18-24) stood even higher at 68%. While these figures alone are alarming enough, given that post-COVID studies have shown widespread deterioration in mental health since this report, it is safe to assume it now more important than ever to address the correlation between mental health and the LGBTQ+ population.

While also seen in film, literature, and almost every other conceivable media form, TV shows are generally regarded the most common culprit of queerbaiting – slow-burning narrative arcs are crafted across entire seasons to develop a relationship between two characters, only to amount to nothing after all. Using this seemingly promised representation to pander to an entire demographic who may not otherwise find appeal in something, is little short of exploitative. The term rainbow capitalism comes to mind, utilising LGBTQ+ themes as a tool for profit. A person’s identity is never something to be capitalised

Series creator Jed Mercurio told Den of Geek in 2021 that the “specific trajectory” of the so-called “Flemson” relationship was scrapped due to COVIDrelated filming limitations. And it is this, more so than the queerbaiting itself, that spotlighted a bigger problem. Queer relationships continue to be sexualised in media, worthy only of representation when they can satisfy the fetish of a heteronormative society through explicit physical intimacy. Because, of course, it is unfathomable that queer couples may communicate with feelings. Whatever way you view it, queerbaiting is fundamentally homophobic. It diminishes LGBTQ+ narratives into little more than figments of our imaginations instead of using valuable platforms to promote affirmative attitudes towards them. And frankly, when media such as film and television is created as a form of popular culture –which is by nature reflective of the society from which it emerged – is it not wholly inaccurate to erase these narratives completely, or reduce the stories that are told to something unworthy of the conventional happy ending?

Gabbi De Boer - Head of Life & Style

Don't buy into everything you see on the internet!

De-influencing: the newest trend that makes us challenge the difference between what items are a want, and what items are a need.

With influencing and influencers being the main form of marketing we encounter on a daily basis, it’s no wonder that, inevitably, we end up with things that we thought were lifechanging. Think about it: we’re faced with a real person (or several) showing us a product and raving about how amazing it is. Can you blame yourself for wanting to buy it?

And that’s the whole basis of de-influencing. Taking place mostly on TikTok, users are taking it in turns to show products that they were influenced into buying. As expected, Dyson air wraps, unique shaped beauty blenders and expensive items of clothing all made the list. They’d taken in the rave reviews, impulse bought the item, and regretted it. At a time where cost of living is at it’s highest, it’s unsurprising that we’re looking into our spending habits with a more critical eye.

As well as this, platforms like TikTok shop advertise such “amazing” deals that it seems you shouldn’t miss, and this partially feeds into it. As attention spans become shorter and the need for instant gratification gets stronger, it seems like a solid way to make money - fast. However, it’s out of control. Social media is so permeated with adverts like these that it’s time to take a step back and accept that we, as a culture, rely so heavily on aesthetics and impulse buying that often times, isn’t worth it at all.

Now, I’m not saying that all of the products are trash and shouldn’t be bought. Most of the time, products just aren’t suited to certain people and their lifestyle habits, which is part of the reason that de-influencing is such a successful trend. Influencer marketing relies heavily on appealing to a mass market, and many products are marketed to a general population. So, although a product may be amazing and ground-breaking to one person, to another, it’s a waste of money. As previously stated, it’s time to start looking more critically at what we buy. It’s time to break free from cycles of consumption and evaluate our wants, and more importantly, needs, in a better way.

Sam Norman - Campus Comment Sub-editor

How can you improve your uni decor?

Minimalism is out (I pray) and maximalism is in. If you want to clutter your house with obnoxious and random decorations please do, but please, no more painfully vacant white rooms.

Hanging Rails

My hanging rail is my life saver. It’s neat, it’s tidy, it reminds me of the jackets I own when I’m tempted to by another. It’s also quick and easy when leaving. And most, like mine, have a shoe shelf attached, could it get any more convenient? My only issue is a lack of coat hangers, but that’s another story, hanging rails get a triple thumbs up.

Plants

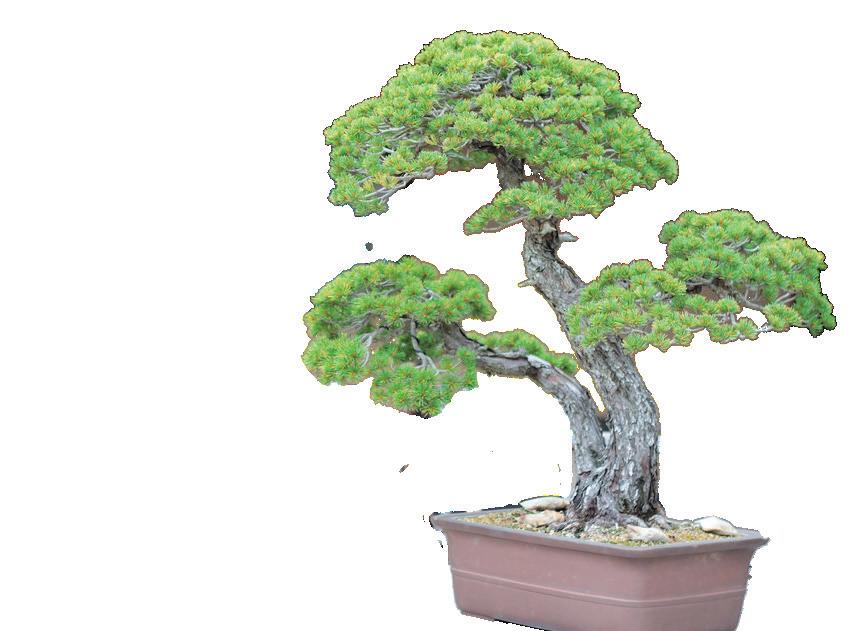

Plants are quite honestly the answer to everything. Bit of empty space? Plants. Need colour? Plants. Void in your soul? Plants. That’s how I got Franklin, my treasured bonsai tree. But don’t fear, real plants aren’t a necessity, fake plants that don’t look tacky are easily situation for students, speaking generally, over the three years at university, we have three different accommodations. Three different bedrooms to make your own, and to live in, something silly and trivial like pictures really enhances the ability to find comfort and make that space your own.