2 minute read

Turkey: who should shoulder the blame?

Annie-Rose Edwards

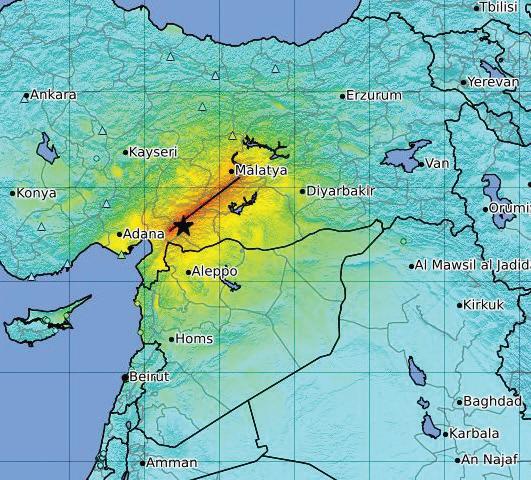

In the early hours of 6 February, a major earthquake hit southeastern Turkey, and was followed by a second, equally destructive aftershock just hours later.

Advertisement

7.8 in magnitude, the quake and the second tremour have caused mass devastation. There are over 40,000 known fatalities, with thousands severely injured and the fate of many missing completely unknown. Official rescue efforts are coming to a close in Turkey, but deaths are expected to rise further, with the UN warning that the final death toll could be over double the current figure.

Yet it wasn’t just the powerful nature of Turkey’s earthquake that lead to such mass destruction. A fortnight after one of the 21st century’s biggest natural disasters, Turkey’s government has found itself under intense scrutiny as criticism grows over the state’s level of preparedness, as well as the speed of the immediate response and the arguably flawed nature of government policies and hazard management plans.

Granted, in a region of Turkey that hasn’t suffered a major earthquake in decades and where, just hours from the border with Syria, political conflict remains at the forefront of conversation, natural disaster management was not pre-emptively prioritised. The reality is that Turkey sits between two major fault lines in an active earthquake zone and experts for years have warned of the region’s vulnerability to a natural disaster of such magnitude. Seyhun Puskulcu, seismologist and coordinator of the Turkish Earthquake Foundation, has admitted that the current catastrophe unfolding “wasn’t a surprise”. All of this begs the sobering question of whether such a devastating disaster could have been avoided if Turkey had been more prepared.

In 1999, northwest Turkey suffered a tragic magnitude-7.4 earthquake, killing more than 17,000 people, in light of which the Turkish government vowed to improve protection against natural disasters, introducing new building codes as well as levying an earthquake tax to raise funds for better preparation for future quakes. However, implementation of the new regulations was weak, with buildings built before the turn of the century remaining unmodified and unable to withstand the intense seismic activity that Turkey was evidently prone to experiencing, leaving many densely populated buildings, including the Iskenderun Devlet Hastanesi hospital - which in 2012 failed earthquake resistance testshighly vulnerable to impending disaster. Further protection efforts have trickled in and out of political conversation, including a complete National Disaster Management Plan which was instituted in 2015 but never actually implemented.

On top of that, serious questions have been raised about how money generated by the state’s earthquake insurance system was actually spent. In short, the Turkish government may have had various plans in place to support its population against the threat of seismic activity, but the bleak reality is that little action was taken. The consequences of this has been all too evident in recent weeks.

But is it all too easy to cast the blame on the Turkish government and overlook the political landscape that has destabilised life at the TurkishSyrian border? The truth is that in both Syria, which has endured more than 11 years of violent conflict, and parts of Turkey, which frequently suffer from their own waves of political unrest, prevailing warfare and political turmoil have rendered it virtually impossible to focus on natural hazard management, including the successful and widespread enforcement of new building standards, because more immediate and pressing problems have seemingly been on the two nations' plates.

In Syria, where years of warfare has steadily destroyed key national infrastructure, buildings in conflictstricken cities have seen themselves provisionally replaced with low quality structures made of any materials at hand. The result of this, with almost 6,000 dead in Syria, is clear and devastating. So, perhaps it’s too easy to make Turkish and Syrian policies the scapegoat of