7 minute read

A kaupapa Māori approach to transitions from kōhanga to kura

Rhan Tangaere (Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga) is a curriculum lead for the Ministry of Education | Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga, supporting early learning services across Te Matau a-Maui and Tairāwhiti. Drawing on lived experience, kaupapa Māori theory and ethnography, Rhan’s research offers a powerful framework for kaiako and kaihautū to strengthen culturally grounded transitions and uphold tino rangatiratanga for whānau Māori.

“Iwas born in 1989 amongst te kōhanga reo movement. We were living in Tītahi Bay at the time which connected us to Ngāti Toa. My father died when I was three months old, so my mother, Taraipine Sharrock (nee Randell), decided to move us home to Heretaunga to be with my nanny. My nanny was a part of Te Kōhanga Reo o Mangaroa.

“With my mother having three children under the age of three years old, my nanna Randell said it was time to come home. We were the first of our siblings to go to kōhanga. My mother, with the support of Ngāti Toa school (Tītahi Bay, Porirua) founded Te Kōhanga Reo o Ngāti Toa in a classroom as a part of the kura. This was my introduction into my ao Māori.”

Rhan’s journey has gone full circle. After school, she became a qualified early childhood kaiako and spent 10 years teaching in both private and public settings. Following her teaching she became a lecturer for the Bachelor of Teaching (Early Childhood Education) for four years before taking on the regional curriculum advisor role for Early Learning, Ministry of Education. Her own tamariki are her “why” and her “purpose”.

“I have loved learning and growing alongside my tamariki throughout my teaching years. After 10 years in both private and public settings, I experienced ‘gaps’ for whānau Māori who were wanting their tamariki to transition from early childhood and te kōhanga reo to kura kaupapa.”

Framing the research

Rhan’s rangahau is guided by two key questions:

What te ao Māori skills support kaiako when transitioning a tamaiti and their whānau from te kōhanga reo to kura kaupapa?

What support (including resources) could be provided to further enhance te ao Māori skills when transitioning a tamaiti and their whānau?

Her methodology draws on kaupapa Māori theory and ethnography. The whakatauākī “Me mārama ki muri, me mārama ki mua” (Tawhiri, 2015b) guides the whakaaro behind her approach.

It emphasises the importance of understanding the past to inform the future. This approach supports a deeper understanding of the historical context and the partnership between te kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori settings within her iwi.

It also supports the research to be grounded in te ao Māori and affirms the legitimacy of Māori ways of knowing, being and doing.

“Kaupapa Māori rangahau validates and affirms what is central to this research – mātauranga Māori, te reo Māori, and Māoritanga,” says Rhan.

Ethnography is valued for its ability to establish in-depth knowledge and experiences of diverse perspectives from kaiako and whānau. Oral pūrākau within the interview process provided evidence of what te ao Māori skills must be used by kaiako to support a successful transition, she says.

“These two methodologies combined will allow the researcher to operationalise mana motuhake for the participants involved. Being guided by tikanga will actively provide a framework through which Māori can determine their stories, values and beliefs within the study.” her pēpi

Rhan used semi-structured interviews to gather kōrero, a method that aligns with kaupapa Māori.

“In te ao Māori, people are given time to speak and to share their stories. Edwards (2010) describes how interviews can take place after observations – this allows the researcher to explore what lies behind observed behaviours and narrow down broad kōrero to get to the core of the kaupapa.”

A framework for transition

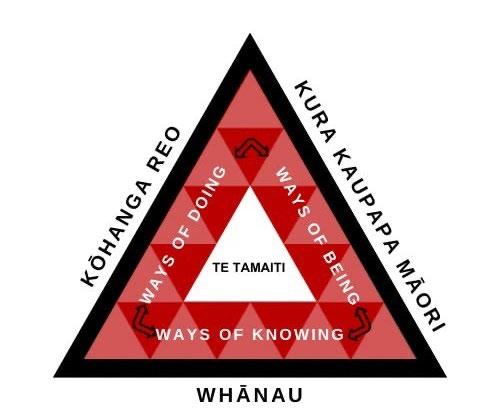

The findings revealed Māori ways of knowing, being and doing for each participant involved. Rhan and her husband, Jorian Tangaere (Pou for wharekura at Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Te Ara Hou), designed a conceptual framework that reflects the research.

“The outsides of the triangle are represented by the names whānau, kōhanga reo, and kura kaupapa Māori. Whānau are placed at the base of the triangle because, within the research, whānau drew mostly on ways of doing and knowing when transitioning their tamaiti from te kōhanga reo to kura kaupapa. However, whānau cannot transition their tamaiti without support.”

Resources that support whānau include:

knowing the kura environment

using te reo Māori within the home

developing knowledge of tikanga through reciprocal relationships

facilitating ako in the acquisition of te reo Māori

promoting tamaiti sense of mana whenua through te reo Māori.

Kura kaupapa kaiako also require resources that include:

inviting whānau to experience kura tikanga

encouraging aroha for te reo Māori

acknowledging kōhanga kaiako and whānau

fostering tamaiti ways of being

supporting tamariki knowledge with kura tikanga and resources.

Te kōhanga reo kaiako contribute through:

mauri tū – whānau valuing the kōhanga environment

mauri ohooho – an open-door policy for whānau

mauri tau – the pathway from kōhanga to kura

a collective vision that kura kaupapa is the correct environment for tamariki Māori.

The placement of the tamaiti in the centre of the triangle reflects the purpose of why te kōhanga reo was established, says Rhan.

Through honouring the aspirations of kaumātua who fought to provide a space to nurture and protect te reo Māori and for all mokopuna to grow, they learn and thrive in an environment that instilled in them te ao Māori values from birth until they transition to kura.

Implications for kaiako and kura

Rhan says her role as regional curriculum advisor (early learning) for the Ministry is a privilege.

“I value the relationships I have built with kaiako within early learning, Te Kōhanga Reo and Puna Reo settings, from Takapau Central Hawke’s Bay right up to Te Tairāwhiti whānui, East Coast.” Rhan’s findings highlight common themes across the kōrero gathered:

Whānau Māori who are on their journey towards te reo Māori revitalisation.

Whānau valuing Te Kōhanga Reo as a collaborative learning environment involving the tamaiti, whānau and kaiako.

Valuing that collective vision that Kura Kaupapa is the correct and appropriate environment for tamariki Māori.

She believes kaiako are the expert kairāranga of Te Whāriki

“The unwoven whenu (strands) resemble the unlimited potential for kaiako to explore new ways of knowing, being and doing in collaboration with a tamaiti and their whānau to continue weaving Te Whāriki.”

Rhan and Jorian’s son, Hunaara, has been in kōhanga since the age of five months. He will be transitioning to kura kaupapa in two years to fulfill the wawata of Rhan’s whānau. Meanwhile Rhan has applied to the University of Canterbury to begin her PhD studies in 2026.

“I have not yet heard the outcome but am hopeful that this research will continue to be recognised.”

Her hopes for the wider education sector are clear.

“This rangahau promotes a sense of whakamana for whānau to ensure tino rangatiratanga is protected, whether whānau have transitioned from te kōhanga reo to kura kaupapa or not – thereby, providing a place for their tamariki to be Māori.”

Kupu | Vocabulary

Te Matau-a-Māui: Hawke’s Bay

Tairāwhiti: Gisborne/East Coast

Kaupapa Māori: Māori approach or philosophy

Kōhanga Reo: Language nest/Māori-medium early childhood centre

Kura Kaupapa Māori: Māori-medium school

Kaihautū: Leader

Tamaiti: Child (singular form of tamariki)

Rangahau: Research

Tikanga: Customs, protocols

Mātauranga Māori: Māori knowledge

Māoritanga: Māori culture, way of life

Whakatauākī Proverb or saying

Kōrero: Talk, conversation, or narrative

Mana motuhake: Autonomy, self-determination

Aroha: Love, compassion

Ako: Reciprocal teaching and learning

Mokopuna: Grandchildren or descendants

Wawata: Aspirations

Kairāranga: Weaver (used metaphorically for educators)

Whenu: Strands (of a woven mat; metaphor for curriculum components)

Tino rangatiratanga: Sovereignty, self-determination