7 minute read

Local News

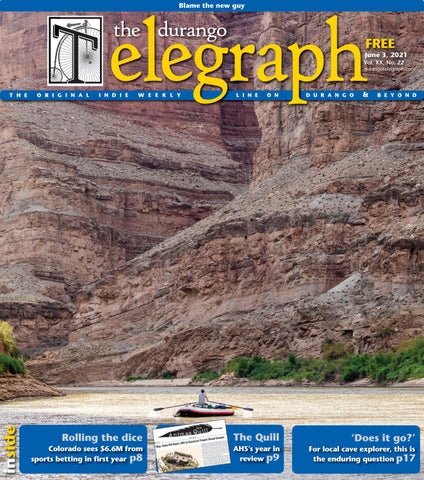

Durangoan Bev Shade navigates a small waterfall in the Cheve cave system in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. Shade recently returned from a two-month expedition of the cave system where she spent 35 days underground. Cheve currently ranks as the 11th deepest cave in the

world./ Photo by Kasia Biernacka

Advertisement

Local cave explorer Bev Shade seeks to find the answer

by Kathleen O’Connor

As a child, Durango resident Bev Shade loved crawling into cramped spaces – beneath beds, inside drawers of bedroom dressers, or even inside the dryer (something we don’t recommend). So, it comes as no surprise that she would discover in her teenage years a passion for caving. For Shade, it all started with the Outing Club at her high school in Austin, Texas.

“They would take kids canoeing or camping or rock climbing,” she explained. And since there’s a lot of caves in Austin, one of the things the Outing Club would do is go to explore these caves. “Shortly after, my best friend and I started looking for an organized caving group,” Shade said. This led them to The Grotto, the Austin chapter of the National Speleological Society (NSS). “After that,” Shade said, “we were able to access more formalized training, how to do the rappelling and climbing stuff that’s specific to caves and how to set the ropes and do the rigging, and go on more organized trips.”

Since those early days, Shade has explored caves worldwide, including Guatemala, Honduras, Argentina, Thailand, Poland and Slovenia. However, her main focus has always been Mexico.

She recently returned to Durango after spending two months – including 35 nights underground – participating in the Cheve Cave System 2021 Expedition. Stationed amid a cloud forest in the Sierra Juárez Mountains of northern Oaxaca, Shade joined an expedition of about 70 deep-cave explorers from eight countries looking to answer the question all curious cave explorers ask: “Does it go?” In other words, do newly discovered passages continue on or are they dead ends? For this particular cave system, the answer was a resounding “yes.” 4

Calcite crystal formations in a small pool./ Photo by Kasia Biernacka

The Cheve cave system, discovered in 1986 by American cavers, has since been the focus of approximately 20 expeditions. The objective of this mission? To push farther, discover and document the Cheve limestone cave system. Expeditions thus far have culminated in a current depth of around 5,000 feet and a total cave passage of 47 miles in length (including numerous offshoots). For comparison, New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns is approximately 30 miles long.

As Shade describes Cheve, “It’s huge.” Over a dozen underground camp stations have been established because traveling to the farthest reaches of the cave, through vertical and horizontal passages – sometimes wet or muddy – loaded down with equipment is so time consuming. Just traveling from the surface to camp can take up to three days. And though there are spacious chambers similar to those found in Carlsbad, this is no simple “walk-through” cave system. “A lot of it is more like a narrow canyon,” Shade said. “When the canyons get blocked by rocks or water, you have to climb up into the ceiling … You’re picking your way around on these boulders until you get to a place where you can get back down into the active stream passage.”

Additionally, much of the travel consists of steep, vertical drops and requires technical gear and ropework. Numerous vertical pits exist along the pathway to the deeper parts of the cave system. For example, the 1,300-foot drop “Saknussem’s Well” (cool points if you get the name reference) has 14 pitches, while a pit drop donned “The Widowmaker” requires you to carefully avoid several loose boulders as you rappel and climb.

Another portion of the cave system called “Salmon Ladders” challenges even the most experienced of cavers. As the name implies, this area is watery. “There are lots of pools of deep water you have to move through,” she said. “And when you’re wearing all that vertical gear, and carrying a heavy pack, getting in and out of the water can be really tiring. And you can get very cold in there, too.”

As one can imagine, living underground can present unique challenges, too. “Probably, the most difficult part for a lot of people is simply being underground for multiple days. It’s tough to keep your clothes dry, much less clean, so hygiene can become an issue,” she said. “And trying to keep your feet healthy becomes difficult because you’re wearing the same pair of socks every day. Extra socks would be too much volume.” When Shade was underground for 21 consecutive days, she only had two pairs of socks: one pair to wear during the day and one pair for sleep. “At about day 14, I switched, and then I started traveling in my sleeping socks and just sleeping with no socks because my other socks had gotten so utterly disgusting,” she said. “You can try to rinse all the silt out, but you’re not really effectively cleaning them, and they never really dry.”

The temperature in the cave remains around 50 degrees Fahrenheit, which Shade described as “quite pleasant,” though nights in the camp-supplied sleeping bags can be chilly. Staying warm is less of an issue during the “day,” when the cavers are busy hauling equipment and supplies to the next camp. However, cold can be an issue in very wet and windy passages, or if you have to stop for an extended time once wet, for example waiting for another team or in the case of an accident. “Managing layers is a big deal,” said Shade.

So, what does a typical hauling day underground look like? It starts at 9 a.m., when you wake up in camp and turn on the radio to listen to the other camp reports. Then, you begin moving food, equipment and tools either back to the camp you just came from or forward to the next camp ahead. Either of those is a full day’s activity. “Then you eat, listen to the 9 p.m. call, make your plan for the next day and go to sleep as soon as possible,” Shade said.

Days like these generally repeat for about six days. Then, a rotation of cavers occurs. Those in active exploration at camp six rotate out, and everybody bumps forward to the next camp. Eventually, making it to the “booty” (i.e. new exploration) at camp six is the reward for the time spent hauling in supplies.

“I got out to camp six, and we explored a lot of new passages there, though I initially didn’t think we were going to be able to dig through it this year,” Shade recalled. The previous three years were spent digging in areas called “Mad Hatter” and “Mad Cows’’ (named after the large, spotted boulders there), laboriously squeezing through boulders and hammering off corners so people could fit through. “Not much mapping occurred because they were mainly trying to squeeze through all of the giant boulders,” Shade said.

Though good leads were unearthed (literally) during the 100 days of the 2021 expedition, there is still much left to discover. At least six entrances to the Cheve system are clustered in the same vicinity at an elevation of 9,000 feet. Far below, at just under 500 feet, are natural springs emerging from the ground, giving this cave system a depth potential of about 8,500 feet. The current deepest cave in the world, in Georgia/Abkhazia, is reported at 7,257 feet deep. Cheve currently ranks as the 11th deepest cave globally, but clearly there’s potential for that to change. And Shade, who plans to return to Cheve next year, hopes to be there when that happens. “There’s not many cave systems like this one,” she said. “It’s definitely gotten under my skin.” n

Top: Shade navigates a wet passage in the Cheve cave system, which she described as more of a narrow underground canyon, with many of the passages choked with rocks and boulders. Explorers have so far mapped 47 miles of the cave system. Left: Shade suits up for a “day” of work. Dry feet are a luxury down under and layering a science, with explorers constantly bat-

tling soggy socks./ Photos by Kasia Biernacka

If you’re curious to learn more about the Cheve cave system and Shade’s adventures there, tune in to National Geographic’s Explorer Series on Disney Plus this fall. Or check out the United States Deep Caving Team (USDCT) website at: www.usdct.org.