11 minute read

Mahler Program Notes

SATURDAY, JANUARY 20TH, 2024 7 PM

DECC SYMPHONY HALL, ALLETE STAGE DIRK MEYER, CONDUCTOR

BLYTHE GAISSERT, MEZZO-SOPRANO

DSSO WOMEN’S CHORUS, MICHAEL FUCHS, GUEST CHORUS MASTER LSYC CONCERT CHOIR, BRET AMUNDSON, DIRECTOR

MAHLER 99’

Symphony No. 3

1. Kräftig. Entschieden

INTERMISSION

2. Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mässig.

3. Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast.

4. Sehr langsam. Misterioso.

5. Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck

6. Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden.

Blythe Gaissert, Mezzo-soprano

Mezzo-soprano Blythe Gaissert has established herself as one of the preeminent interpreters of some of the brightest stars of new classical music. A true singing actress, she has received critical acclaim for her interpretations of both new and traditional repertoire in opera, concert, and chamber repertoire. “Gaissert gave a dramatically powerful, vocally stunning portrait of a woman growing increasingly desperate and delusional from lack of contact with the outer world. Gaissert’s development of Loats’s personality was utterly believable, and she gave a virtuoso performance of this very challenging music’ (Arlo McKinnon, Opera News for The Echo Drift). Known for her warm tone, powerful stage presence, and impeccable musicianship and technical prowess….

(Denver Post)

In the 19-20 season, Ms. Gaissert created the role of Dorothy in the world premiere of Kamala Sankaram and Rob Handel’s Looking At You with Here Arts Center NYC, sang Gertrude Stein in Ricky Ian Gordon and Royce Vavrek’s 27 with Intermountain Opera Bozeman, Hannah After in As One with Opera Columbus and Opera Memphis, covered Margret in Wozzeck at the Metropolitan Opera, sang Hansel in Hansel and Gretel at San Diego Opera, performed the world premiere of a chamber piece by John Glover and Kelly Rourke with Echappe Ensemble, sang Beethoven 9 with the Fort Worth Symphony, performed the world premiere of songs by Kamala Sankaram, David T. Little and Martin Hennessy with Sybarite5 as well as the world premiere of Robert Paterson’s Autumn Songs with American Modern Ensemble at Carnegie Hall. Blythe finished out with a recital of Brahms and Schubert with the Brooklyn Art Song Society.

In the 2018-19 season, Ms. Gaissert created the role of Georgia O’Keefe Today It Rains with San Francisco’s Opera Parallele, the world premiere of the third opera by the highly acclaimed and record setting team of As One: Laura Kaminsky, Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed. She also reprises her role as Hannah After in her 6th production of As One with New York City Opera/American Opera Projects, performed Beethoven’s 9th Symphony with both the Buffalo Symphony and Sarasota Orchestra, and performed in a workshop performance of Laura Kaminsky’s fourth opera, also with librettist Kimberly Reed, Postville: Hometown To The World with Opera

BLYTHE GAISSERT

Fusion: New Works in conjunction with Cincinnati Opera and her alma mater Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music. Recent engagements include Berio Folk Songs and Siegrune Die Walkuere with the Dallas Symphony, and Berlioz L’Enfance du Christ with the Orquesta Sinfónica y Coro Rtve conducted by Miguel Harth-Bedoya.

Previous engagements include Carmen, Orlovsky Die Fledermaus, Hansel Hansel und Gretel, Siegrune Die Walkure, Lucretia Rape Of Lucretia, Maddalena Rigoletto, Suzuki Madama Butterfly, soloist in the Verdi Requiem, Berio Folk Songs, Mozart Requiem, world premieres by John Adams, Laura Kaminsky, Mikael Karlsson, Robert Paterson, Martin Hennessy, Mohammed Fairouz, Richard Pearson Thomas, Glen Roven, Yotam Haber, Jorge Martin, Tom Cipullo, Renee Favand-See, Gilda Lyons, Jessica Meyer, Gabriel Kahane and more. Companies with whom Ms. Gaissert has performed include the Metropolitan Opera, Los Angeles Philharmonic, LA Opera, Dallas Symphony, San Diego Opera, Prototype Festival, Aldeburgh Festival, Lyrique en Mer, Tulsa Opera, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Sarasota Opera, and Opera Saratoga.

“Mezzo-soprano Blythe Gaissert was impossible to ignore as the headstrong Mother Marie. She has a pure, powerful and appealing voice and a forceful stage presence to match.”

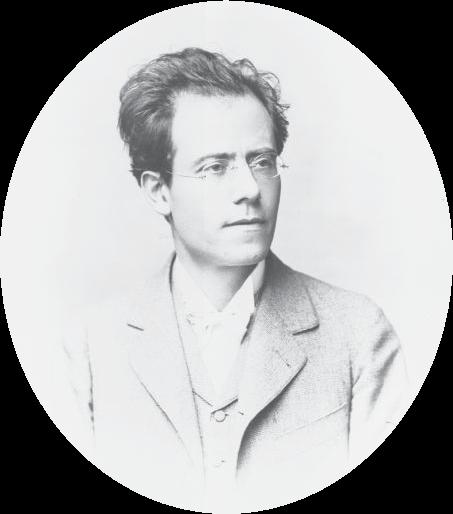

GUSTAV MAHLER

Symphony No. 3 in D minor GUSTAV MAHLER

BORN: July 7, 1860, in Kalischt, near Iglau, Bohemia [now: Kaliště, Jihlava, Czech Republic]

DIED: May 18, 1911, in Vienna, Austria

WORK COMPOSED: 1895-96

WORLD PREMIERE: June 9. 1902, Krefeld, Germany; Festival Orchestra of the German Musical Association (Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein), Mahler conducting

PERFORMANCE HISTORY: Tonight marks the first DSSO performance of this Mahler Symphony

INSTRUMENTATION: Four flutes (all doubling piccolo), four oboes (4th doubling English horn), four clarinets and E-flat clarinet (3rd doubling bass clarinet, 4th doubling E-flat clarinet), four bassoons (4th doubling contrabassoon), eight horns, four trumpets (one doubling posthorn), four trombones, tuba, timpani (two players), percussion (bass drum, snare drums, cymbals, triangle, tambourine, tam-tam, rute (bundle of attached canes for hitting drums), glockenspiels, chimes), two harps, strings, alto solo, women’s and children’s chorus.

DURATION: 99 minutes

Mahler’s Third Symphony belongs to the early period of his life and to his own personal quest for life’s meaning in the face of suffering and death. As a young man Mahler suffered great personal losses; his father died early in 1889 followed by the deaths of both his sister and mother later that same year. Suddenly, at the age of 29 and already in poor health, Mahler became a guardian of his four younger siblings. A worse tragedy befell Mahler when his younger brother Otto shot himself in February 1895. Faced with these challenges he was deeply affected by his encounter with the works of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Mahler’s First Symphony, Titan, focused on heroism and earthly existence. His approach to redemption in his Second Symphony, Resurrection, is that humankind is subservient to God’s grace achieved through belief. The Third Symphony is Mahler’s attempt to experience all that nature has to offer in a quest to reach higher forms of existence, until ultimately forming a union with God and humanity.

The Third Symphony is the longest symphony in the standard repertoire and in a survey of conductors carried out by the BBC Music Magazine, was voted one of the ten greatest symphonies of all time. The Third has six movements and is divided into two parts. Part One is the first movement alone and Part Two consists of the other five movements. As he did with all of his first four symphonies, Mahler provided a programmatic description to explain the narrative of the piece, however he was ambivalent about the use of these descriptions. The following messages give an excellent example of Mahler’s diverse opinions regarding descriptive program notes, this to the critic Max Kalbeck in 1902:

Beginning with Beethoven there is no modern music without its underlying program. But no music is worth anything if you first have to tell the listener what experience lies behind it and what he is supposed to experience in it. And so yet again: to hell with every program! You just have to bring along ears and a heart along and - not least - willingly surrender to the rhapsodist. Some residue of mystery always remains, even for the creator.

At about the same time he wrote to the conductor Josef Krug-Waldsee:

Those titles were an attempt on my part to provide non-musicians with something to hold on to and with a signpost for the intellectual, or better, the expressive content of the various movements and for their relationships to each other and to the whole. That it didn’t work (as, in fact, it could never work) and that it led only to misinterpretations of the most horrendous sort became painfully clear all too quickly. It’s the same disaster that had overtaken me on previous and similar occasions, and now I have

once and for all given up commenting, analyzing all such expediencies of whatever sort. These titles . . . will surely say something to you after you know the score. You will draw intimations from them about how I imagined the steady intensification of feeling, from the indistinct, unbending, elemental existence (of the forces of nature) to the tender formation of the human heart, which in turn points toward and reaches a region beyond itself (God). Please express that in your own words without quoting those extremely inadequate titles and that way you will have acted in my spirit. I am very grateful that you asked me [about the titles], for it is by no means inconsequential to me and for the future of my work how it is introduced into “public life.”

When Mahler completed the Third, dated August 6, 1896, the subtitle of the work was simply A Midsummer Noon’s Dream. The individual movements were titled:

First Part: Pan Awakes. Summer Comes Marching In

Second Part: What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me

What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me

What Humanity Tells Me

What the Angels Tell Me

What Love Tells Me

Critics of Mahler have great fun with these titles; Mahler was a flower-child long before it came into vogue. However, the titles of the movements disappear by the Third Symphony’s first publishing.

Mahler acquired a one-room cabin at Steinbach on the Attersee, about twenty miles east of Salzburg, in 1893 where he would spend summers composing. In the summer of 1895 his sister Justine (1868-1938) and his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858-1921) accompanied him there to look after him, which meant basically to silence the crows, waterbirds, children and whistling farmhands, as he began composing the Third Symphony. I’m reminded of Ken Russell’s 1974 film Mahler where a young woman (most likely Justine) is running all over silencing every possible noise that might be a disturbance to Mahler.

Part One opens with a declamatory fanfare that is heavy and menacing. Mahler described the effect of this opening to Bauer-Lechner: “Over the introduction to this movement, there lies again that atmosphere of brooding summer midday heat; not a breath stirs, all life is suspended, and the sun-drenched air trembles and vibrates.” A second theme, with winds and solo violin, offers some light into the ominous gloom. Several of the themes heard near the beginning will be transformed into material for the last three movements (fascinating in that Mahler wrote the first movement after the others). The entire movement is a series of marches that continue to build, becoming more

and more impassioned. A return to the menace of the opening march cuts off that section. The climactic ending of Part One is nothing short of breathtaking. The orchestra is playing at full force as Mahler instructs “mit höchster Kraft” (with all possible strength). This is certainly a place where not only the audience, but the orchestra as well needs a well-deserved break. After the first movement in the Second Symphony, Mahler calls for a short pause before beginning the remainder of the work; a break is recommended between Part One and Part Two of the Third Symphony.

Part Two, except for the finale, is a series of short character pieces beginning with Blumenstück, the first music he composed for this symphony Blumenstück is a minuet that is interrupted with a sinister section with brief moments of frantic activity, only to return to the gentle minuet. The third movement harkens back to his First and Second Symphonies. The love of nature in the First Symphony and the great summoning at the end of the Second Symphony are evoked.

The fourth movement enters with low strings and provides a foundation for the solo alto. Nietzsche provides the words to the Midnight Song from Also sprach Zarathustra with each of its eleven lines to be imagined as coming between two of the twelve strokes of midnight. “Oh man, give heed! What does deep midnight say? I Slept! From a deep dream have I waked. The world is deep. And deeper than the day had thought! Deep is its pain! Joy deeper still than heartbreak! Pain speaks: Vanish! But all joy seeks eternity. Seeks deep, deep eternity.”

As dark as Nietzsche’s midnight is, the change to a world of bells and angels is most welcome. The text for the fifth movement comes from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn) with interjections of Mahler’s words Du sollst ja nicht weinen (But you mustn’t weep). The children’s chorus is at first confined to bell noises but joins in later with the exhortation Liebe nur Gott (Love only God) and the final stanza. Mahler ends the Third with an exceptionally beautiful Adagio. As he explained to Bauer-Lechner, “In adagio movements everything is resolved in quiet. The Ixion [Ixion was a king who, by Zeus’ command, was pinned to a fiery wheel that revolved unceasingly through the underworld, as punishment for his alleged seduction of Hera] wheel of outward appearances is at last brought to a standstill. In fast movements - minuets, allegros, even andantes nowadays - everything is motion, change, flux. Therefore I have ended my Second and Third symphonies contrary to custom… with adagios - the higher form as distinguished from the lower.”

The final movement’s original title, What Love Tells Me, refers to Christian love, to agape, and Mahler’s drafts include “Behold my wounds! Let not one soul be lost!” And as Michael Steinberg writes, Mahler’s performance directions also speak to spirituality; the immense final bars with the thundering timpani are not to be played with brute strength, but with a rich, noble tone and the last measure should “not be cut off sharply” - so that there is some softness to the edge between sound and silence at the end of this profound utterance of serene power and beauty.