11 minute read

Masterworks 5 Program Notes

ASH MICHAEL TORKE:

Born: September 22, 1961, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin Work Composed: 1988 World Premiere: February 3, 1989, in St. Paul, Minnesota, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, John Adams conducting Performance History: The Orchestra performs Ash for the first time this evening. The only other work by Torke performed on the Masterworks Series was Bright Blue Music, given on March 6, 2010 with Markand Thakar conducting. Instrumentation: Flute, two oboes, clarinet, two bassoons, three horns, trumpet, timpani, synthesizer and strings.

Michael Torke is one of the leading American composers of his generation. In the Minimalist era of Philip Glass, John Adams, Steve Reich, Terry Riley and others, composers created series of notes that would be repeated numerous times, now and then adding an additional note or two creating forward momentum. John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986) or Arvo Pärt’s Fratres are prime examples of this compositional style. By incorporating musical techniques from both the classical tradition and the contemporary pop world Torke has defined the Post-Minimalist era.

As a young classical piano student, Torke was immersed in classical music and it wasn’t until he attended the Eastman School of Music that he ‘discovered’ jazz and rock. The pulsating, driving rhythms of jazz and rock strongly influence his compositions. “The idea that rhythm is intrinsically human — not just primitive — that we all have hearts that beat at a steady rate and don't stop...reminds me of life itself. In that sense my music is like certain popular music where the rhythm drives from beginning to end.” Torke also has a strong sense of synesthesia, associating specific colors with notes, keys or chords. Individuals rarely agree on what color a sound is; D might be blue for one person and green for another. Both Franz Liszt and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov were known to have synesthesia and would disagree on the colors of musical keys.

The St. Paul Chamber Orchestra commissioned Ash with support from the Jerome Foundation. Torke provided the program notes:

In trying to find aclear and recognizable language to write this piece, I have chosen some of the most basic, functionally tonal means: tonics and dominants in F minor, a modulation to the relative major (A-flat), and a three-part form which, through a retransition, recapitulates back to F minor. What I o er is not invention of new "words" or a new language but a new way to make sentences and paragraphs in a common, much-used existing language. I can create a more compelling musical argument with these means because, to my ears, potential rhetoric seems to fall out from such highly functional chords as tonics and dominants more than certain fixed sonorities and Pop chords that I have used before. My musical argument is dependent on a feeling of cause and e ect, both on a local level where one chord releases the tension from a previous chord and on the larger structural level where a section is forced to follow a previous section by a coercive modulation. The orchestration does not seek color for its own sake, as decoration is not a high priority, but the instruments combine and double each other to create an insistent ensemble from beginning to end. Only occasionally, as in the middle A-flat section, do three woodwind instruments play alone for a short while to break the inertia of the ensemble forging its course together.

MICHAEL TORKE

PIANO CONCERTO IN ONE MOVEMENT FLORENCE PRICE:

Born: April 9, 1887, in Little Rock, Arkansas Died: June 3, 1953, in Chicago, Illinois Work Composed: 1933 World Premiere: June 24, 1934, in Chicago, Chicago Musical College Orchestra, composer as soloist Performance History: Tonight marks the DSSO’s first performance of any music by Florence Price. Instrumentation: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, two trombones, timpani, percussion (bass drum, snare drum, crash cymbals, triangle), strings and solo piano.

Florence Price is the first African-American woman to be recognized as a symphonic composer and the first to have a composition played by a major orchestra. She was one of three children born into a mixed-race family. Despite the racial issues of the time, her family was well respected. Her father was a dentist and her mother a music teacher who began Florence’s musical training at a young age. The young Florence was a truly a gifted child and she graduated as valedictorian of her class at age 14. She then enrolled in the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston majoring in piano and organ. She graduated with honors in 1906 with both an artist diploma in organ and a teaching certificate. She taught briefly after returning to Arkansas before moving to Atlanta, Georgia in 1910 where she became head of the music department of what is now Clark Atlanta University, a historically black college. In 1912 she married attorney Thomas J. Price and moved back to Little Rock where he had his practice. After a series of racial incidents in Little Rock, particularly a lynching of a black man in 1927, the Price family moved north to Chicago in hopes of escaping the Jim Crow conditions.

Price’s musical career flourished in Chicago. She met and studied with the leading teachers in the city. In 1928 she published four pieces for piano. At various times she was enrolled at the Chicago Musical College, Chicago Teacher’s College, University of Chicago, and American Conservatory of Music, studying liberal arts and languages as well as music. Financial struggles and spousal abuse led to her getting a divorce in 1931. As a single

FLORENCE PRICE

mother to two daughters she worked as an organist for silent movies and, under a pen name, composed songs for radio ads. During this time she lived with friends and eventually moved in with her student and friend, Margaret Bonds, who was also a black pianist and composer. This connection was to propel Price onto the national stage. Through Bonds, Price met writer Langston Hughes and contralto Marian Anderson, both of whom aided Price in her future success as a composer. In 1932 Price submitted her Symphony in E minor for the Wanamaker Foundation Awards and won first prize. On June 15, 1933, Frederick Stock conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the premiere of Price’s symphony, making it the first composition by an African-American woman to be performed by a major orchestra.

Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement was premiered one year later. Although it is in one movement there are three distinct sections played without a break, similar to the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. In listening to this work I was struck by how delightful and enjoyable it is. My first thought went to Gershwin’s Piano Concerto, but the comparison is unfair and not necessary. Price incorporates elements of African-American spirituals, emphasizing their rhythm and syncopation. The melodies are blues-inspired and mixed with the more traditional European Romantic techniques. She performed the premiere in 1934 and most likely performed it a subsequent number of times, but then it seemed to disappear from view.

Fast forward to 2009 and a dilapidated house on the outskirts of St. Anne, Illinois. A large stockpile of manuscripts by Florence Price was discovered and thankfully whoever found them knew they were important. Trevor Weston, at the behest of the Center for Black Music Research, was tasked with reconstructing Price’s works. Because the Piano Concerto had been performed a number of times in the 1930s, there were more sketches, arrangements and also an incomplete set of orchestra parts found, but the original orchestra score is lost and has yet to surface. Alex Ross stated in The New Yorker in February 2018, “not only did Price fail to enter the canon; a large quantity of her music came perilously close to obliteration. That run-down house in St. Anne is a potent symbol of how a country can forget its cultural history.” Learning about Florence Price and listening to recordings of her works has been one of the highlights for me of this otherwise miserable year. Her music lifted me up when I needed a boost and I sincerely hope you enjoy this true gem from this incredibly talented woman.

SYMPHONY NO. 4 IN A MAJOR, OP. 90, ITALIAN FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Born: February 3, 1809, in Hamburg, Germany Died: November 4, 1847, in Leipzig Work Composed: 1833, revised 1837 and 1847 World Premiere: May 13, 1833, in London at a Philharmonic Society Concert, Mendelssohn conducting Performance History: The Orchestra performs this work for the 12th time on the Masterworks Series. It was also heard in 1937, 1945, 1950, 1953, 1960, 1964, 1969, 1976, 1993, 1999 and on March 9, 2013. The November 13, 1976 performance was led by DSSO Music Director Candidate Taavo Virkhaus. It was the first piece on the program. Taavo later become the Orchestra’s sixth Music Director from 1977 to 1994. Instrumentation: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings.

“This is Italy!” Mendelssohn wrote to his father while on his journey of Italy (from October 1830 until his return to Germany in October 1831). His journey started in Venice, followed by stops in Bologna and Florence on his way to Rome. While in Rome he witnessed the coronation of Pope Pius VIII and the festivities during Holy Week. From Rome, before returning to Germany via Genoa and Milan, he went to Naples and visited Pompeii. While in Rome he wrote to his sister Fanny, “The Italian symphony is making great progress. It will be the jolliest piece I have ever done, especially the last movement. I have not found anything for the slow movement yet, and I think that I will save that for Naples.” Mendelssohn was a reasonably good amateur artist and, through a series of watercolors and sketches, recorded his impressions of Italy. The monumental art, architecture, open countryside, religious solemnity and Mediterranean sunshine are conveyed in the Italian Symphony.

The trip to Italy was spurred on by the urging of his friend Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his composition teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter. He began the trip with a two-week visit in Weimar with Goethe, which would be the last time they would be together as Goethe died while Mendelssohn was in Italy. In his February 22, 1831, letter to his sister he reported, “I have once more begun to compose with fresh vigor…” Yet it wasn’t until November 1832, when the Philharmonic Society of London o ered Mendelssohn a sizable commission for a new symphony, among other pieces, that he decided to move forward with this new symphony. The Italian Symphony was hugely successful at its premiere. However, the composer had misgivings and soon began making changes in the score, much to the objections of both his sister Fanny and his friend Ignaz Moscheles, who wrote of the premiere in his diary, “Mendelssohn was the outstanding success of the concert, he conducted his magnificent A major Symphony and received rapturous applause.” With such

great success, it is di cult to understand Mendelssohn’s displeasure. He made two revisions, in 1837 and again before he died in 1847, but it was never published in his lifetime and he never allowed the Italian Symphony to be played in Germany during his lifetime. The final version, which is regularly performed today, was premiered on November 1, 1849, in Leipzig with Julius Rietz conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra.

The Italian Symphony grabs hold from the very first notes; the vigorous, joyful and extroverted character embraces you like the proverbial Italian family inviting you over for dinner and all of a sudden you’re one of them. As is normal there are numerous conversations going on at the same time and just when you begin to feel overwhelmed a solo oboe sings out with a single note (A), held for nine and a half measures, then moves to a similarly extended F-sharp, grabbing your attention back to the original conversation.

The second movement, an Andante con moto, recalls the processions Mendelssohn witnessed while in Rome. The prevalent and near constant motion of the bass-line gives the impression that while this may be a solemn procession, it has direction and purpose. The third movement minuet is a love-poem that is humorous and sensual. Perhaps Mendelssohn thought the mood would evoke the then-current stereotypes of Italians as openly amorous.

The musical portrayal of Italy sparkles in the finale. After the opening five introductory notes the strings perform a saltarello rhythm that comes from Tuscany in the 15th century. Very popular in southern Italy, Mendelssohn would have certainly witnessed this lively dance during the celebratory festivities in Rome. The name comes from the Italian verb saltare, meaning ‘to jump’. Dance is the theme of the entire finale as Mendelssohn also introduces a tarantella during the development section. He then combines both dances to bring the Italian Symphony to a whirlwind finish.

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

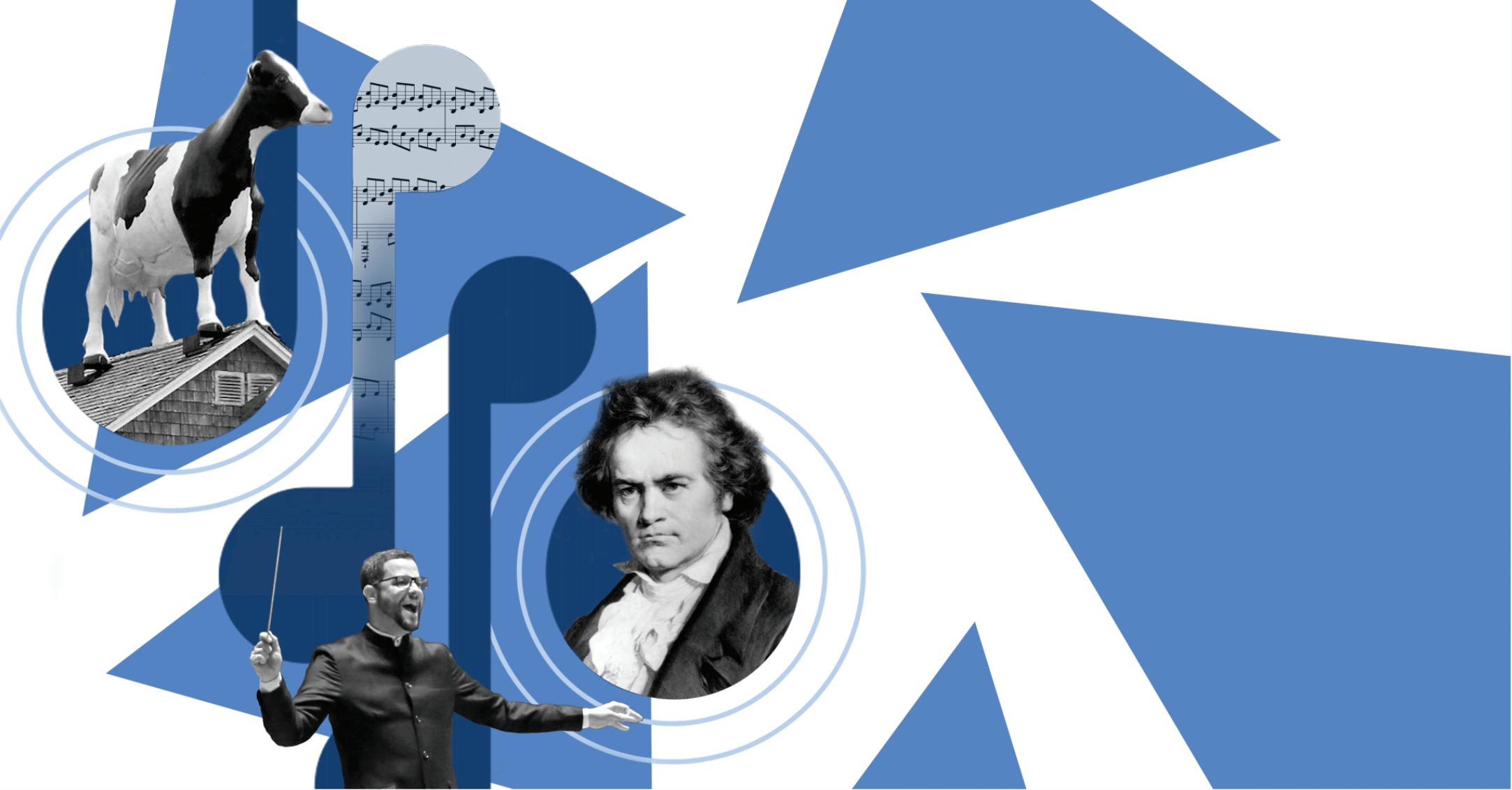

FROM BEETHOVEN TO MILHAUD

SATURDAY MAY 8, 2021 7 PM DECC SYMPHONY HALL, ALLETE STAGE

DIRK MEYER, MUSIC DIRECTOR JENNIFER GERTH, CLARINET

Yousufi: Freedom 3’

Mozart : Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 25’ Allegro Adagio Rondo Allegro

Golijov: ZZ‘s Dream 7’

Milhaud: Le Bœuf sur le Toit, Op. 58 15’

Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b 15’

Sponsored by: