20 minute read

5th

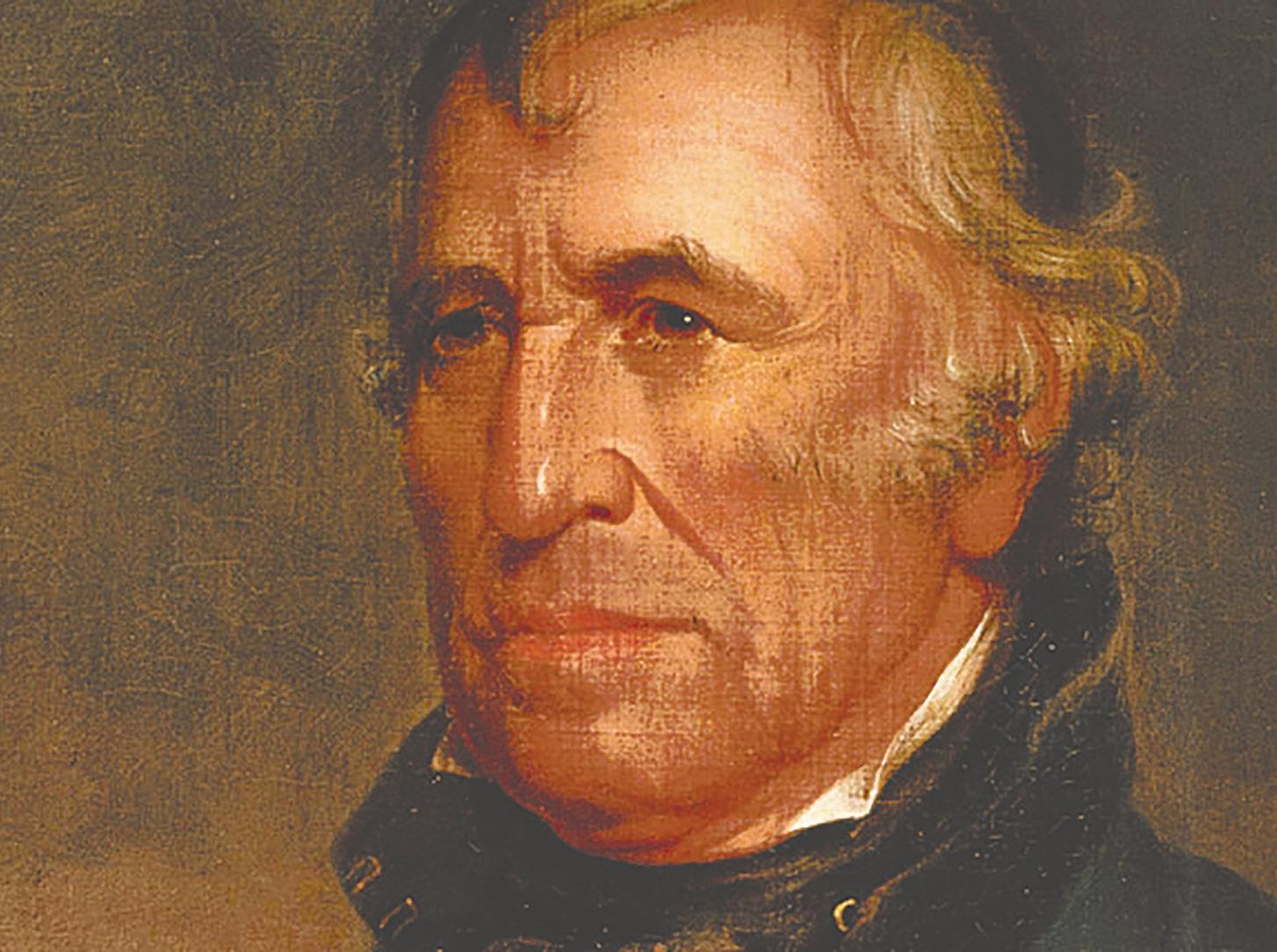

James Monroe was born on April 28, 1758 in Westmoreland County, Virginia . He attended the College of William and Mary before joining the Continental Army, where he was wounded at the Battle of Trenton in 1776. It is Monroe who is depicted holding the flag in the famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware . The image is also depicted on the back of the New Jersey state quarter. After the war, he practiced law in Fredericksburg and married Elizabeth Kortright in 1786. To learn more about Elizabeth Monroe, click here Monroe’s political career moved quickly in the new nation. He participated in the Continental Congress from 1783 to 1786 and was elected as a Virginia Senator in 1790. From 1794-1796, he served as Minister to France during the French Revolution.

From 1799-1802, he served as Virginia ’s Governor and he served as Minister of the Court of St. James (Ambassador to England) from 1803 to 1807 in Thomas Jefferson’s administration. During the Madison administration, Monroe served at various times as Secretary of State and Secretary of War.

In 1816, James Monroe was elected America ’s fifth president. His presidency lasted two terms from 1817–1825 and was referred to as The Era of Good Feeling because of the relative lack of political bitterness between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republican Party. The “good feeling,” however, was short-lived as a painful economic depression swept through the country as a result of the Panic of 1819. That same year, Congress became locked in a bitter debate over the admission of Missouri as a slave state that finally ended with the Missouri Compromise in 1820. As part of the compromise, Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine as a free state.

Monroe is probably best known for the Monroe Doctrine, a document largely written by John Quincy

Adams. The document outlined America’s foreign policy stance and proclaimed neutrality in European affairs. It also condemned European colonization and declared that such colonization in North and South America was a direct threat to the United States.

After his second term in office ended in 1825, Monroe lived at Monroe Hill on the campus of the University of Virginia. The current campus served as Monroe’s farm from 1788 to 1817, when he sold it to the university. Racked by debt, he lived a humble existence before moving to New York City after the death of his wife in 1830. He died on July 4, 1831, of tuberculosis and heart failure, becoming the third president to die on July 4. He was originally buried in New York City but now lies in Richmond, Virginia. In 1824, the capital city of the African nation of Liberia was renamed Monrovia in his honor. It is the only foreign capital named after a US president.

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, to Abigail and John Adams in Braintree, Massachusetts. John Quincy was largely raised by his mother because his father was heavily involved in the American Revolution. Early on in the Revolutionary War, John Quincy Adams feared his family would be kidnapped or killed because his father signed the Declaration of Independence. John Quincy witnessed the war firsthand as his hometown was so close to the center of Revolutionary action. Soldiers often marched right through his yard. From the ages of ten to seventeen, John Quincy accompanied his father on a special convoy to Europe, where he spent seven years traveling to Prussia, the Netherlands, England, and even Paris, where he went to school with the grandsons of Benjamin Franklin. John Quincy returned to the United States in 1785 and enrolled in Harvard as an advanced student, graduating in just two years with a law degree.

After graduation, John Quincy opened his own law firm in Massachusetts but quickly eschewed law for a career in politics. After John Quincy’s father was elected president in 1796, he sent John Quincy to be the minister to Prussia. When Adams lost his bid for reelection to Thomas Jefferson in 1800, Jefferson recalled John Quincy, bringing him back to the United States. After he came back to the States. In 1802 John Quincy was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate and then the US Senate.

When James Monroe became president in 1817, he appointed John Ambassador to the Russian Court. His stint as ambassador to Russia was temporary as he was called to Belgium to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, which was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812. John Quincy was then named Secretary of State in the Monroe cabinet and was the architect behind the Monroe Doctrine, which aimed to prevent European colonization in Latin America by affirming that the United States would provide protection over the entire Western Hemisphere. The Monroe Doctrine was America’s first articulation of foreign policy. Together with James Monroe and other American politicians of the time, Adams helped to usher in a period of American history known as the Era of Good Feeling.

In 1824, John Quincy Adams won one of the most controversial presidential elections in American history, becoming the nation’s sixth president. In the election, neither Adams nor Andrew Jackson received the majority of electoral votes, leaving it to Congress to determine the victor. In what came to be known as the “corrupt bargain,” it is believed that John Quincy offered Senator Henry Clay the Secretary of State position if he convinced Congress to elect him president instead of his opponent,

Andrew Jackson. The corrupt bargain angered many Jackson supporters and even caused Jackson to resign from the Senate.

John Quincy’s term as president was marred by controversy created by his political enemies (Jackson supporters), who aimed to block any new legislation he supported. During his presidency, industrialization intensified in the Northern United States, highlighted by construction of the Erie Canal.

Adams was also successful in paying off much of the national debt.

In 1828, John Quincy ran for reelection against Andrew Jackson but was defeated, becoming only the second president to fail in a reelection bid (the first was his father). After the loss to Jackson, John Quincy returned home to Massachusetts, where he served in the House fighting for the abolition of slavery. John Quincy Adams died in 1848.

Andrew Jackson was born in South Carolina on March 15, 1767. He was the third son of Andrew and Elizabeth Jackson, immigrants from Northern Ireland. Jackson’s father died days before he was born. As a youngster, Jackson experienced no formal education but spent several years reading and studying law. At the age of 20 he was admitted to the bar. In 1788, he was appointed public prosecutor of the western district of North Carolina. He would soon settle in Nashville, Tennessee, and become a successful lawyer.

In Tennessee, Jackson met Rachel Donelson Robards who would eventually become his wife. Jackson and Rachel believed that Captain Robards had received a legal divorce by the Virginia legislature, but the marriage was not officially dissolved until 1793. This stunned the righteous Jackson and the couple was properly remarried in 1794. Jackson’s enemies would claim that he stole another man’s wife and lived with her for three years. These claims did not sit well with Jackson and often invoked his famous temper. Jackson killed

Charles Dickinson, a fellow lawyer, in a pistol duel for insulting Rachel. As Jackson continued to prosper in Tennessee, he built his famous mansion, the Hermitage, near Nashville.

On March 4, 1823, Andrew Jackson was elected senator of Tennessee. The next year, he ran for the Presidency of the United States. His opponent in the election was John Quincy Adams. Neither Jackson nor Adams won the majority vote, and the election was to be determined in the House of Representatives. Henry Clay, who lost the presidential election, was still the speaker of the House of Representatives. Clay was a friend and advocate of Adams and lobbied hard for his election. Adams eventually won and appointed Clay to be his secretary of state. Jackson and his supporters cried foul. They believed that corruption, thievery, and crooked politics had cost him the election. These events would drive Jackson’s campaign in 1828.

In 1828, Jackson won the election by a landslide and became the nation’s seventh president. He was seen as the people’s pres- ident. He received 178 electoral votes to Adams’s 83. Jackson wasted no time in putting his mark on the presidency. Jackson claimed that the old corrupt politicians had to go. He removed almost the entire old regime and replaced them with people he chose. In 1828, however, Rachel died and Jackson became depressed.

In 1832, Andrew Jackson took measures to take away the federal charter of the Second Bank of the United States. Jackson believed the bank was unconstitutional, too powerful, exposed the nation’s finances to foreign interests, favored northeastern states, and was corrupt. Eventually, Jackson succeeded in this endeavor, and the bank’s charter was revoked. Hundreds of state and local banks took over the national bank’s lending functions.

Andrew Jackson is perhaps best known for his Indian removal programs. In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized Congress to purchase Indian lands in the east in exchange for unsettled land in the west. Jackson’s actions were particularly popular in the south, as gold had been discovered on Cherokee lands in Georgia. Jackson pressured Cherokee leaders to sign a removal treaty (known as the Treaty of New Echota) that was surely rejected by most Cherokee people. The treaty, which was enforced by Martin Van Buren, resulted in the removal of the Cherokee Indians from their native lands via the Trail of Tears. The Cherokee were forced to walk hundreds of miles from Georgia to present-day Oklahoma. Thousands died along the way. In all, more than 45,000 Indians were “removed” during Jackson’s administration.

Andrew Jackson retired to his mansion in Tennessee after his second term. He died on June 8, 1845, at the Hermitage

Martin Van Buren was born on December 5, 1782, in Kinderhook, New York. Van Buren’s parents were Dutch farmers and taught him the Dutch language before he learned English. He attended school at a village schoolhouse until the age of 14. At the age of 16, however, Van Buren began studying law at the office of prominent Kinderhook attorneys. By 1803, Van Buren was admitted to the New York State Bar at the age of 21.

In 1807, Van Buren married Hannah Hoes, his first cousin once removed. Hoes was raised in a Dutch home and spoke English with a strong accent. The Van Buren’s would eventually have five sons, four of which survived into adulthood. In 1819, Hannah died of tuberculosis. Martin would never re-marry. To learn more about Hannah Hoes Van Buren, click here.

Van Buren’s family had been involved in politics from the time he was a child, and Martin became involved shortly after becoming an attorney. In 1815, he was elected Attorney General (top legal official) for the State of New York while serving in the state’s senate, where he fought for increased soldier pay and expansion of New York’s militia. He soon gained political influence and was nicknamed “the Little Magician” for his skill in ensuring his political supporters were awarded government jobs and incentives for remaining loyal. This practice was known as “the spoils system,” and became an accepted aspect of politics. Van Buren’s political cronies would eventually organize themselves into the Democratic Party.

Van Buren served as senator of New York from 1821 to 1829. In 1829, he was elected as governor of New York. Van Buren’s term as governor was the shortest in the history of the state, largely because newly elected president Andrew Jackson appointed him as Secretary of State on March 5, 1829. In 1831, he strategically resigned as Secretary of State in the wake of the Petticoat Affair, in which members of Andrew Jackson’s cabinet and wives refused to associate with Secretary of War John Eaton and his wife because of disapproval over the circumstances of their marriage. Jackson, however, was fond of Van Buren, and appointed him as his vice-presidential running mate in the Election of 1832. When Jackson was elected president, Van Buren became his vice-president. As vice-president, Van Buren was one of Jackson’s most trusted advisors and stood by Jackson in contentious issues such as the Nullification Crisis of 1828, in which South Carolina attempted to void a federal tariff that it claimed hurt its economy and favored the North.

In 1837, with Jackson’s support, Van Buren was elected as America’s eighth president.

During his presidency, Van Buren was tasked with dealing with the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis that resulted in five years of economic depression. Like his predecessor, Andrew Jackson, Van Buren supported measures to remove Native Americans from their lands to reservations in Oklahoma. Throughout his presidency and after, Van Buren opposed the abolishment of slavery, even though he believed the practice to be immoral. Van Buren would be blamed for the country’s precarious economic position and was defeated by William Henry Harrison in the presidential election of 1840.

Although Van Buren sought to return to the White House, political missteps cost him any real chance of election.

Van Buren died on July24, 1862, at the age of 79.

William Henry Harrison was born into an influential political family on February 9, 1773, in Charles City County, Virginia. Harrison’s father was a wealthy Virginia planter who signed the Declaration of Independence and later became governor of Virginia.

Harrison attended Hampden-Sydney College and studied classics and history. He next moved to Richmond to study medicine. In 1791, after the death of his father, Harrison stopped studying medicine and joined the US Army. He was sent to the Northwest Territory (present-day Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois), where he served as an aide to “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Under Wayne, Harrison learned how to command an army of frontier soldiers.

In 1798, Harrison resigned from the US Army and became Secretary of the Northwest Territory. In 1799, Harrison was elected as a delegate representing the Northwest Territory in Congress. After helping to gain passage of the Harrison Land Act, which made it easier for settlers to buy land in the Northwest Territory, Harrison resigned as a delegate from Congress and became governor of the Northwest Territory. As governor, Harrison secured a vast expanse of land at the expense of the Indians who inhabited it. Indian resistance, under the leadership of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, would soon become violent. In 1811, Harrison and 1,000 soldiers marched to Prophetstown, Indiana (an Indian village), for the purposes of removing the Indians. An epic battle ensued known as the Battle of Tippecanoe, in which Harrison and his men massacred the Indians. Later, in the War of 1812, Harrison commanded an army that routed the British at the Battle of Thames (in present-day Ontario). Harrison instantly became a war hero.

After serving in both the Ohio Senate and House of Representatives, Harrison was elected to the US Senate. He served in the Senate until he was appointed Minister to Colombia in 1828. In 1836, Harrison ran for president of the United States but was defeated by Martin Van Buren. In 1840, Harrison again ran for president and was elected in a landslide victory. Harrison’s vice president was John Tyler. Their catchy campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” is one of the most famous in American history.

Harrison took office on March 4, 1841. That day, Harrison delivered the longest inaugural speech in American history—in the bitter cold. Harrison quickly developed a cold, which turned into pneumonia. Despite intensive medical treatment, Harrison died just one month later. He was the first president to die in office. To this day, his presidency was the shortest in American history—32 days.

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790 in Charles City County, Virginia. Tyler was one of eight children and was born into a wealthy family. His father was a tobacco planter and judge at the U.S. Circuit Court at Richmond, Virginia. By the time John was twelve he was enrolled at the College of William Mary and graduated at 17.

After college, John studied law with his father, who had been elected as Governor of Virginia (1808-1811). John was admitted to the Virginia state bar in 1809 and began practicing law in Charles City County . His political career began in 1811 when he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates (Virginia General Assembly today). From 18161821 he served in the Virginia House of Representatives before returning to the House of Delegates. In 1825, he was elected Governor of Virginia and served for two years. From 1827 to 1836, John served as Senator. In 1840, Tyler switched political allegiance to the Whig party after it promised to make him the vice-presidential running mate of presidential candidate

William Henry Harrison in the upcoming election. “Tipeecanoe and Tyler too,” was their famous slogan and Tyler was inaugurated as vice-president in 1841. Just a month after inauguration, William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia and Tyler ascended to the presidency. He would become the first president to ascend to the presidency because of the death of the president. Tyler ’s rise to the presidency was controversial and many detractors referred to him as “His Accidency,” because he “accidentally” became president. Nevertheless, Tyler insisted on taking on the full duties of the president.

Tyler, however, had plans to put his personal stamp on the presidency (much to the dismay of the Whigs). Although it was thought Tyler would strictly adhere to Whig policies and ideals, he repeatedly vetoed legislation introduced by Whig party members, including two banking acts proposed by the influential Henry Clay. As a result, the president was expelled from the Whig Party and became “the man without a party.” Furthermore, the entire cabinet appointed by Harrison resigned within a year of Tyler ’s ascent.

Tyler struggled in his presidency to be taken seriously and had a contentious relationship with Congress. Nevertheless, his presidency produced several positive outcomes. His Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, negotiated the Waterton-Ashburton Treaty that fixed the border between

Maine and British Canada and ended hostile relations between the two nations over the disputed borders. In addition, The “Log-Cabin” bill enabled a settler to claim 160 acres of land before it was offered publicly for sale, and later pay $1.25 an acre for it. In 1845, the Republic of Texas was annexed and granted statehood, making it the nation’s largest state. On his last day in office, Florida was admitted as a state.

After his presidency, Tyler retired to his plantation in Charles City County. He renamed his land “ Sherwood Forest ,” as a final jab at the Whig Party that had expelled him. During the Civil War, he sided with the Confederacy and even became a member of the Provisional Confederate Congress. Tyler died in 1862. Because of his support for the Confederacy he was the only President whose death was not mourned in Washington . Furthermore, he is considered the only president to have died outside of the United States (his death occurred when Virginia had seceded from the Union.). During his life he married two women, Letitia Christian, who died in the White House in 1842, and Julia Gardiner, whom he married after the death of his first wife. Tyler would have fifteen children in all, eight with his first wife and seven with his second. He is buried in Richmond, Virginia.

James K. Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, in 1795. He graduated with honors from the University of North Carolina in 1818. As a young man he became a successful lawyer, entered politics and joined the Tennessee Legislature. Polk’s political career progressed quickly. He served as the Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1835-1839. He served as governor of Tennessee afterwards. He would earn the nickname “Little Hickory,” for his close association to Andrew Jackson, who was called “Old Hickory.”

In 1844, Polk was elected president of the United States – the first and only Speaker of the House to ever ascend to the presidency. He was an advocate of Manifest Destiny (western expansion) and supported the annexation of Texas, as well as acquisition of California and Oregon. Later that year, Polk negotiated a treaty with Great Britain which resulted in his country’s acquisition of the Oregon Territory. Although Texas became the 31st state in 1845, the attempted acquisition of California resulted in the Mexican-American War. Polk initially offered to buy California and the New Mexico territory from Mexico for $20,000,000, plus forgiveness of other debts. The Mexican government refused, which prompted Polk to send general (and the next president) Zachary Taylor and his troops to the region. The Mexicans saw this as a sign of aggression and attacked Taylor’s troops.

Congress declared war and promptly defeated Mexican forces and occupied Mexico City. At the end of the war, Mexico agreed to give up California and the New Mexico territory for $15,000,000. The new lands increased the land mass of the American nation significantly.

Polk’s presidency is regarded as very successful and he is considered by historians to have been the most successful single-term, non-assassinated president. During his presidency, the first postage stamps were issued, the Smithsonian museums were dedicated, and the United States Naval Academy was opened.

In failing health, Polk left the White House in 1849 (he never tried to win re-election). Only 103 days after his last as president, he died of Cholera in Nashville, Tennessee.

Zachary Taylor, the 12th President of the United States, was born on November 24, 1784. Taylor was born in Barboursville, Virginia to a wealthy family of planters.

In 1808, Zachary Taylor joined the army as a first lieutenant of the Seventh Infantry Regiment. By 1809, he was commissioned as an officer in the United States Army. Soon after his commission as an officer, he was made a captain in 1810. One year later in 1811, Taylor was sent to Fort Knox where he took command and received honors for his successful restoration of order among the men serving at Fort Knox. Taylor continued to prove himself a solid leader for the United States eventually rising to the rank of Major General. His victories during the Second Seminole War resulted in his nickname “Old Rough and Ready.”

During his short presidency, Taylor was instrumental in admitting California as an official state of the Union. Taylor also helped to settle state border disputes between Texas and New Mexico that would bring the western territories of the United States together.

In July of 1850, Zachary Taylor was diagnosed with cholera morgues. Cholera was a common digestive illness of the time. A fifty foot tall monument was placed near his grave in Louisville, Kentucky by the Commonwealth of Kentucky to memorialize his life and presidency.

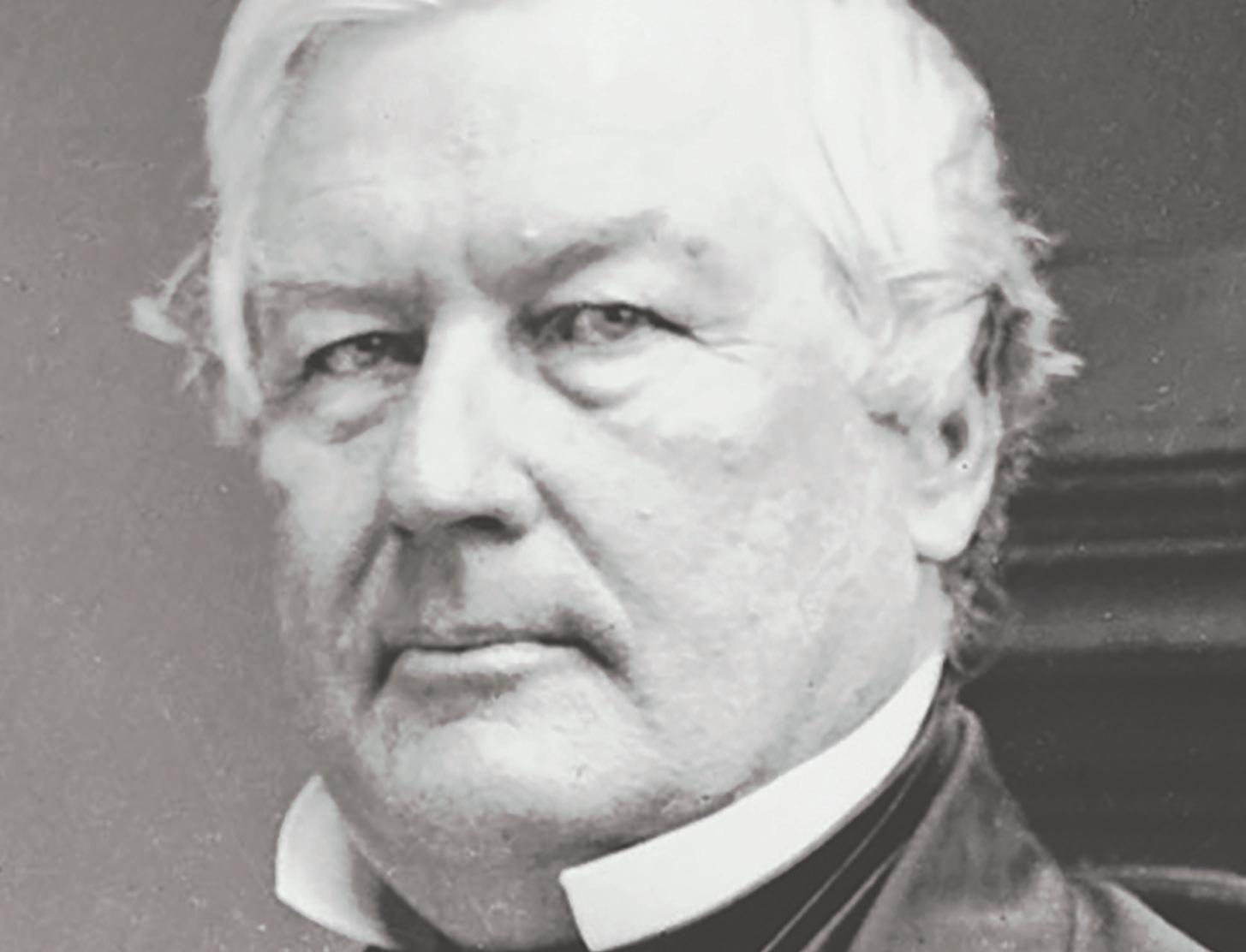

Millard Fillmore was born on January 7, 1800, in Cayuga County, New York. He had eight brothers and sisters. As a teenager, Fillmore served as an apprentice to a cloth maker but received little formal education apart from briefly attending New Hope Academy in New Hope, New York. In 1819, he began to clerk for Judge Walter Wood in Montville, New York, whom he studied law under. In 1823, he was admitted to the New York bar and started practicing in East Aurora, New York (near Buffalo). In 1826, he married Abigail Powers. The couple would have two children.

Fillmore’s law career moved quickly. In 1836, he formed the practice Fillmore, Hall & Haven, which would become one of western New York’s most successful firms. In 1846, Fillmore founded the University of Buffalo, which today is the largest university in the State University of New York (SUNY) system. From 1832 to 1843, Fillmore served in the New York State Assembly as a Whig. From 1848 to 1849, he served as New York State Comptroller.

In 1849, Fillmore was selected as Whig presidential candidate Zachary Taylor’s running mate.

In 1850, President Zachary Taylor died unexpectedly, and Fillmore was sworn in as the 13th president. He would be the last Whig president and the first president to have been born after the death of George Washington.

Fillmore’s presidency was dominated by dissention in the Whig Party and by the growing division over the question of the extension of slavery into new states. In what came to be known as the Compromise of 1850, California was admitted to the Union as a free state, the New Mexico Territory was established, and the Fugitive Slave Law was enforced in the Northern states, enraging some Northern members of the Whig Party.

As the dissention over the slavery issue caused the disintegration of the Whig Party, Fillmore joined the Know-Nothing Party, an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant party that believed America was being overrun by immigration. Like the Whigs, the Know-Nothing Party soon disintegrated and Fillmore’s political career ended. In 1862, he founded the Buffalo Historical Society and became its first president. Fillmore died on March 8, 1874, of a stroke.

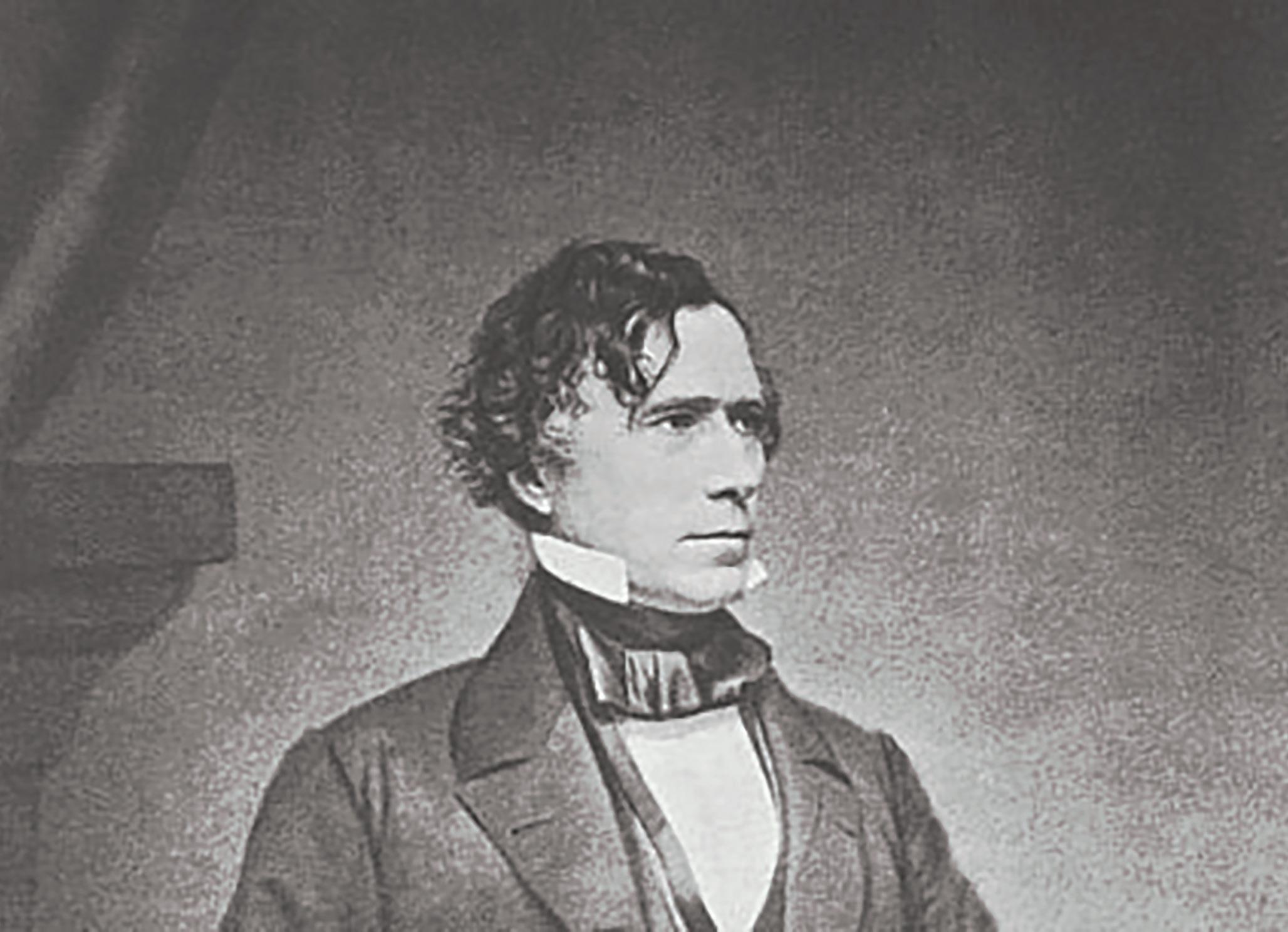

Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States, was born on November 23, 1804, in Hillsborough, New Hampshire. Pierce was more than just a career politician he was both a successful lawyer and brigadier general in the United States Army, during the Mexican American war.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Pierce entered politics at an early age. By the age of 24, Franklin Pierce was elected to the New Hampshire legislature. When he was only 26 years old, he was appointed Speaker of the New Hampshire legislature. Next, his political career led him to Washington, DC, as an elected representative and eventually a Senator for the state of New Hampshire.

In 1853, Franklin Pierce became the 14th President of the United States. Tragedy stuck the Pierce family just two months prior to Franklin taking the office of president. The couple’s eleven-year-old son, Benny, was killed when the family’s train derailed. Despite the horrendous tragedy, Pierce endured and took the office while still grieving for his child. During his presidency, Franklin Pierce embraced westward expansion and supported popular sovereignty in Kansas, which allowed the citizens of Kansas to decide whether or not to allow slavery there.

Pierce’s stance angered many abolitionists, who referred to him as a “doughface,” a northern politician who sympathized with the South. During his presidency, Pierce also approved the Gadsden Purchase, which added parts of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico to the United States. Pierce’s presidency, however, is remembered for its inability to stem the rising tide of secession, and its failure to solve sectional conflict. Some historians rank his presidency as among the worst of all presidents.

His support in the North was further compromised as he became a vocal critic of Abraham Lincoln. President Pierce struggled his entire life with alcoholism and died at age 64, from cirrhosis of the liver.

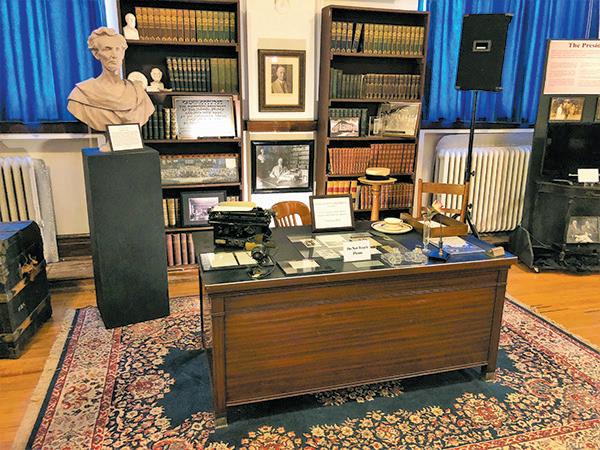

James Buchanan was born on April 23, 1791, near Mercersburg, Pennsylvania.

He was the second of ten children. In 1809, he graduated from Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, even though he was previously expelled from the school for bad behavior. After graduating, he studied law and was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1812. In the War of 1812 against Great Britain, Buchanan fought in the defense of Baltimore.

Buchanan’s political career began in 1814 in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. He next served in Congress as a representative for Pennsylvania from 1821–1831. From 1832 to 1834, he served as the United States Ambassador to Russia. In 1834, he was elected to fill a vacancy in the US Senate and was reelected in 1837 and 1843 before resigning in 1845. He next served as Secretary of State under President James

K. Polk and negotiated a treaty that designated the northern boundary of the western United States at the 49th parallel. This was known as the Oregon Treaty. After the Polk administration, Buchanan continued his work in foreign relations and served as ambassador to Great Britain.

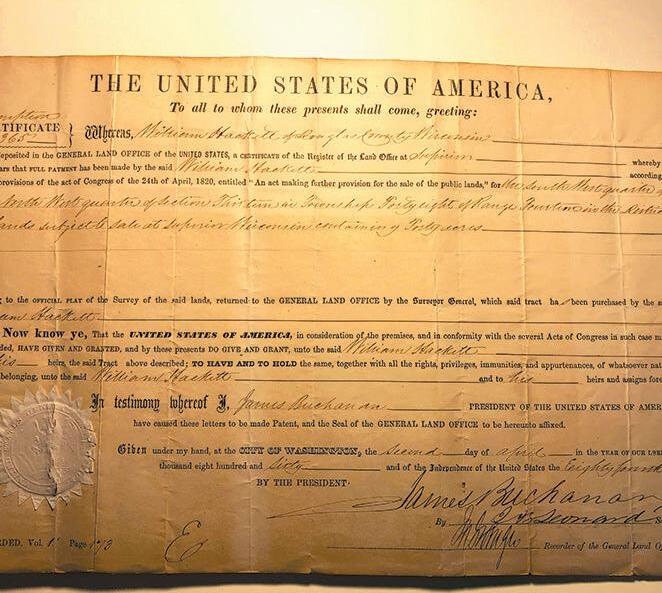

In 1856, Buchanan was nominated for president by the Democratic Party. Buchanan defeated the Republican candidate John C. Fremont and was elected the nation’s 15th president. Immediately, his presidency got off to a controversial start as Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, which asserted the Constitution did not authorize the right to prohibit slavery in the new territories. Buchanan, who was sympathetic to the Southern cause, was decried by abolitionists after he lobbied for the cause of slaveholders. Abraham Lincoln even suggested the outcome may have been a conspiracy of slaveholders to gain control of the federal government. During the Bleeding Kansas controversy, Buchanan supported the LeCompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas to the Union as a slave state. Even though the LeCompton Constitution was rejected by Kansas voters,

Buchanan managed to pass the bill through the House of Representatives (although it was rejected by the Senate). Buchanan’s pro-slavery position infuriated Northerners and weakened the power of the Democratic Party by alienating some of its members. By 1860, the Democratic Party had split into a Northern and Southern contingency, each nominating its own candidate for the