5 minute read

30°44’ 7”N 88°3’31”W

The hidden history of Africatown isn’t a wives’ tale. It’s time for the story to be told and accountability to be taken. | Story by Gracie King. Photos by Michael Dunn, and courtesy of Mobile Public Library.

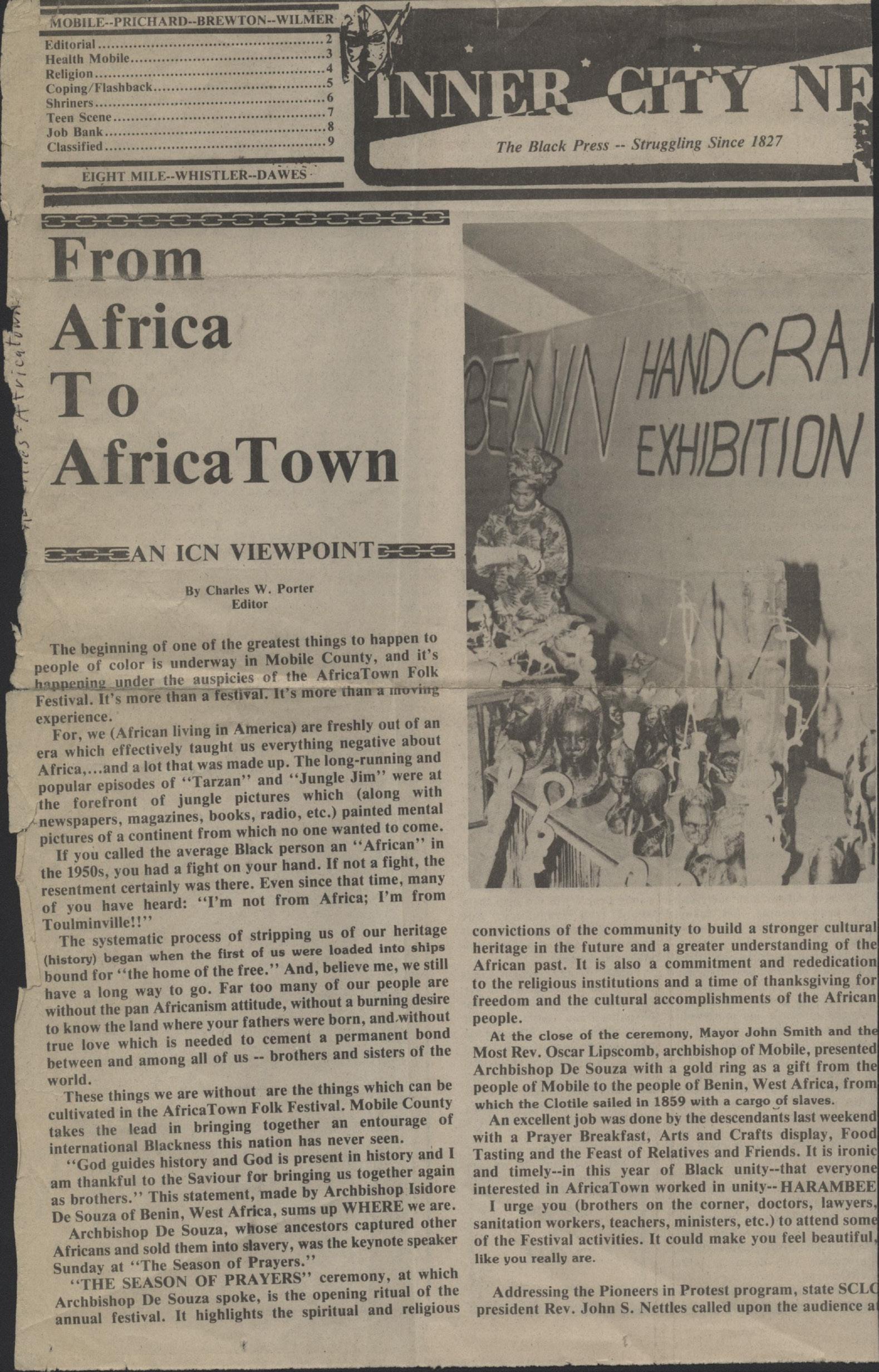

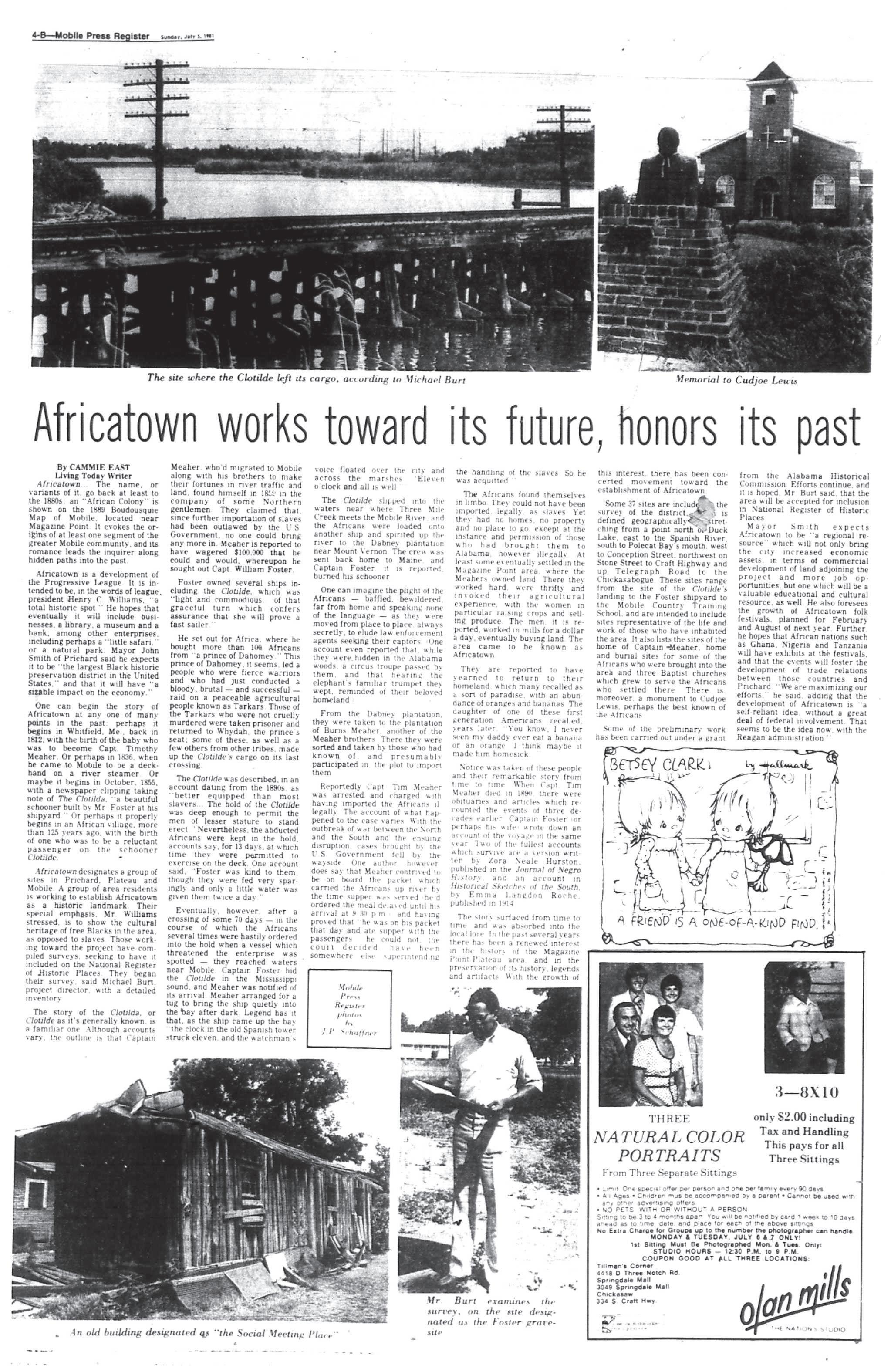

Africatown sits on the west bank of the Mobile River on the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, just three miles north of downtown. This now 57-acre community was originally settled by 32 formerly enslaved West Africans, most of whom were illegally imported to the Mobile Bay on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in America.

Advertisement

A few years before the Civil War began, Timothy Meaher, a wealthy Mobile shipyard owner, drunkenly bet a group of businessmen that he could import enslaved people to the states from the Kingdom of Dahomey in Africa without being caught. Though this kind of activity became illegal in 1808 by The Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves, Meaher and co-conspirator Captain William Foster began building a

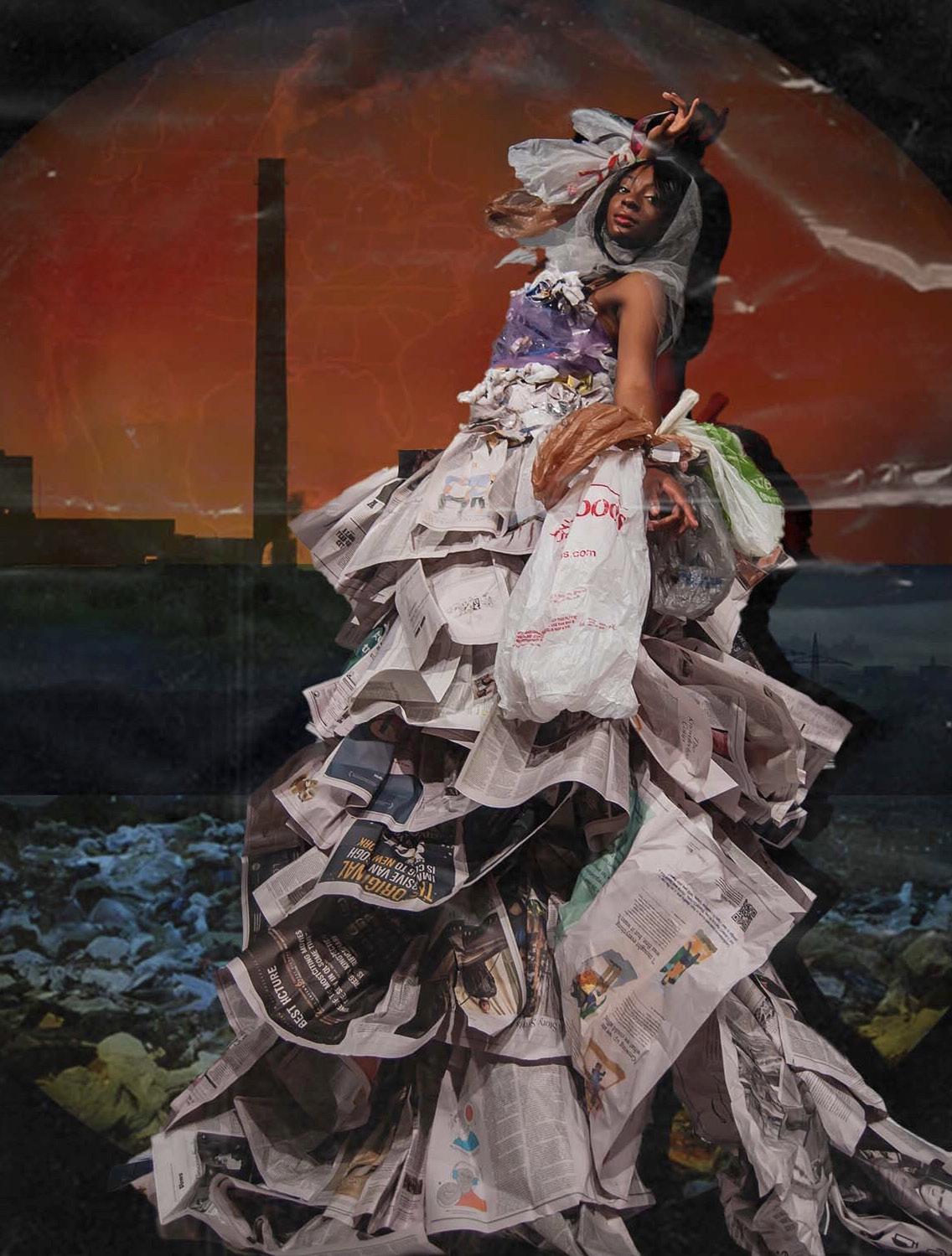

As the thick, coastal fog of the Mobile Bay rolls in, a two-masted, 86 foot long boat made from yellow pine and white oak with a coppersheathed hull and packed to the brim with enslaved prisoners trudges through the dreary water. The creaking of the full slats and whistle of the wind disguises the dismal and puzzled wails of those trapped below the surface, anxiously awaiting the new world they’ll be later forced to serve.

This is the gut-wrenching true story of the Clotilda and the community later forged from their resilient human spirit.

30°44′7″N 88°3′31″W

schooner and set sail in March of 1860. With $9,000 worth of gold in tow, Meaher and Foster negotiated prices with the King of Dahomey, who was selling enemy prisoners into slavery.

110 West African men, women, and children were crammed into the rough slats of the Clotilda and began the tortuous journey back to America.

Shortly after being towed to Twelve Mile Island, the enslaved people were ordered out while Foster burned the Clotilda to the waterline in order to avoid the authorities. After being forced to wait in the swamps of the Mobile Bay, Meaher came to retrieve and divide them amongst his friends, some not even staying in Alabama. When the Civil War ended, many of the formerly enslaved people came to Meaher for passage home but were swiftly denied. Instead of purchasing land for them or sending them home on his dime, Meaher agreed to sell them land on the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta. This is where Africatown still proudly stands today, a beacon of its former ancestors and hope for the future.

Many citizens of Mobile Ala. would like the world to forget about this particular stain. Before the remains of the Clotilda were discovered in 2018 by journalist Ben Raines, the story was often referred to as an old wives’ tale by some Mobile natives. Though there’s living proof of this atrocity, the city

and its residents were able to turn a blind eye to the struggles faced every day by the community.

In 1928, the International Paper plant was built along the edge of Africatown, offering a boost to the struggling economy of Africatown. Joycelyn Davis is a life-long resident of Africatown, direct descendant of the original Clotilda passengers, breast cancer survivor, and next in line to be the official historian of Africatown, preceded by Lorna Gail Woods. She fondly remembers her father being able to buy a car, a house, a boat, and comfortably pay their bills due to his job at the paper plant.

She also remembers seeing pollution from the plant on a daily basis.

Davis recalls about her walks home from school. Many residents of Africatown have since developed various forms of cancer, for which they received a settlement based on the devolution of property due to pollution, not personal damages. Though this community desperately needs and deserves the support of the city, many of its residents simply want recognition of their disenfranchised reality. Since the discovery of the ship’s remains, the Meaher family, still a prominent presence in Mobile Ala., has yet to admit the family’s involvement in the community’s dark history or attempt to make personal amends with its citizens. They also still own and are remembered through much of the land in Africatown, made clear by their bright “FOR LEASE” signs and Meaher Street and Timothy Avenue landmarks.

More than anything, the town deserves visibility for its past. Many Alabama citizens aren’t even aware of the Clotilda’s existence.

The best support we can offer the community is engaging in conversations that we normally wouldn’t. Dr. Kern Jackson, director of the African American Studies Program at the University of South Alabama, offers his students opportunities to take advantage of the history around them and immerse themselves in the reality of Africatown.

Jackson observed about the importance of connecting with members of the community.

As the story lives on, the empowerment in its tellers grows stronger each time it is repeated. The sturdy roots of the past have yielded generations parched for justice with an unquenchable thirst. It is imperative that their reality is looked at from a critical lens by all willing to listen and willing to advocate for change.