3 minute read

A SONG FROM THE WOOD

from Entengo Combination Of Herbal Products For Penis Growth In Empangeni City In South Africa

by Tribe Group Distributors Of Herbal Sexual Products In South Africa

In all manner of humanity. The motherly gaits and ‘Nam vets, the floral sun hats and deviant tats, the thick, the slight, the white, brown and black. And try, apply or taste: Organic soaps, desert-specific allergy stoppers and local-farm asparagus, and so on. Under a decorative race-horseand-jockey silhouette perched high on a pavilion, this Tucson farmers market is stoked in the springtime heat.

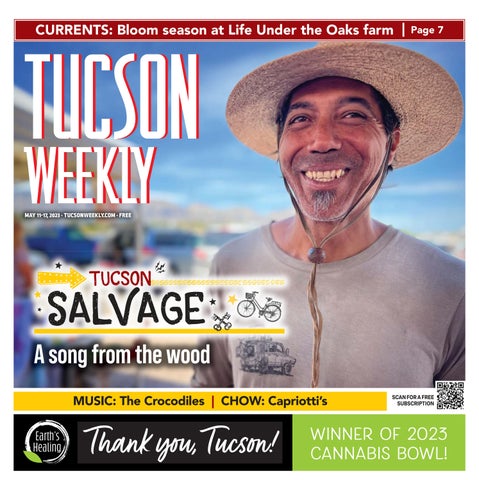

Somewhere amidst the proliferate rows of booth vendors and sun-venerating shoppers, and with no fanfare, not even a sign or business card, Romny Guillen stands behind a portable folding table, lithesome, an extensive grin and benign eyes under a straw guardian hat, a wrist wrapped in Mala prayer beads. He talks to anyone.

Advertisement

There is a quiet authority about him, suggests otherworldliness, buffers the noisy flow. English is his second languageafterSpanishandwhenhespeaks his voice lifts to a certain volume and never exceeds it. His table brims with trimmings of Arizona trees — mesquite, ash, chokecherry, etc. — hand-carved into spoons, forks and knives.

Folks stop and shell $15 for a wooden cooking utensil, a steal considering it took him years scraping, chiseling, layering and sanding, of diligence and craft, to perfect this precise skill.

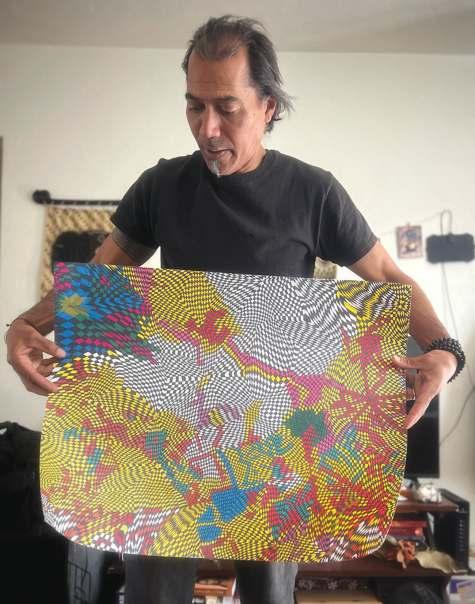

The table centerpiece is a chuck of mesquite, the size of something a child could sit on. River-like swirls of tiny turquoise stones set in epoxy resin make it an alchemical dream of a thing, hand sanded and oiled, like some beautiful, aerial photorealist take of a rainforest.

Sprinkled about the table are little eyes out to the world, old bottle caps fitted with antique marbles and disparate finds like seashells and turquoise.

There is a calming beauty to this artist’s work, and folks who approach his table today sense a real deal. He enthuses of wood in a studious torrent of types, colors, strengths and aesthetics and they inspect his hand-carved one-of-a-kindness work in awe. A footshaped fork of mesquite, a spoon tiny as a fingernail.

He explains using his hands over electric tools, no different from his drawings and other art. “How I like to do things. I could make a hundred of these spoons a day with electric tools, power tools. But it takes me out of the zone.” His eyes squint in the sun, he laughs, adds, “Anyway, they’re just so noisy and

Someone will request a custom object, a wooden hairclip, for example, and Romny shakes his head. “It throws me off. So, I don’t really do that.” He doesn’t promote his work, either, zero social media. “I used to have Etsy and Facebook,” he said, shrugged, “I just don’t do that anymore.”

It stands to reason. He could sell a lot of his work. Today he’ll earn $300. Instead, he earns a living helping others through his art, and the art itself is his way to find calm in the world.

***

Romny was born into an impoverished childhood, grew up in the developing Dominican Republic. He likes to talk about its people, the animals, the trees, the way the sun felt, how it relates to a spirituality he tuned into as a kid.

He told of his mother hauling laundry to the river, dirt floors under feet, bumming 20-minute rides to dial a phone number. Surviving on food they could grow or pull out for roots, milk from animals, out on the grandparent’s rural farm. “For me, being a kid, it was like paradise, and there was food everywhere, fruit on the trees,” Romny said. “For my mom, not so much.”

He learned to build a fire, carve a hunted bird and cook it at age five. He learned to read young too, and was absorbed by the wilds of the outdoors, which turned creative, and soon he was drawing, building, and creating his own colorful kites.

Later, the family moved to the city, Santo Domingo. Still, he said, “we could count on the electricity going out every day.”

The alcoholic dad, who among other things (a teacher, a cop) became a star baseball player in a country mad for the sport. Sometimes he’d play drunk. He got out and traveled with a triple A team in America.

“He was a catcher, at the time one of the best players in the DR,” Romny said. Memories of his father are vague, a man floating in and out of the picture. “He lost all of his jobs because of his drinking,” Romny said. “But he was a very kind person.”

In the 1980s, souring economic conditions in the Dominican Republic saw immigration to the United States surge, Romny’s family part of it.

At 12, Romny arrived in the South Bronx, a Puerto Rican neighborhood, then a woebegone land of abject poverty, a ripe crack epidemic, all built on institutional racism. Romny remembers this 37 years later. His uncle and cousin collecting them at the airport and driving in. “I was looking at a skyscraper, thinking it would be nice to live in a building like that.” Oh, the excitement, the energy of a land of milk and honey, of opportunity, of sustenance and abundance. They kept driving, a cityscape growing progressively uninviting, until arriving on a street featuring gutted buildings, a burned down factory. The uncle stopped the car and said, “We’re here!”

“Oh, man,” Romny said. “And my school was at the end of the block.”

The family, mom, dad, sister, two brothers, couldn’t speak a lick of English, got by on Spanish. The family