14 minute read

FREEDOM

from Common Sense 2025

by drroysmythe

Freedom In Modern America

“If ye love wealth better than liberty, the tranquility of servitude better than the animating contest of freedom, go home from us in peace. We ask not your counsels or arms. Crouch down and lick the hands which feed you. May your chains set lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen.”

Samuel Adams

To punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, in 1774 the British Parliament passed The Coercive Acts (what the American colonists not surprisingly called The Intolerable Acts). The laws closed Boston Harbor, dissolved local charter government in Massachusetts, allowed any British official to bypass colonial justice and be tried in Britain, and forced quartering of redcoats in American homes. After almost a decade of “taxation without representation” and street skirmishes with British troops - it's an understatement to say the colonists were not at all amused. Less than a year later, on a warm March day in 1775 the Virginia planter Patrick Henry (1736-1799) rose in the dusty sanctuary of the St. John’s Episcopal Church at the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond, and uttered the phrase most every American fifth grader can proudly recognize and recite (…at least the last seven words):

“The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

What most fifth graders and beyond may not know; however, is as Henry uttered these last seven words, he took in his hand an ivory paper cutter (letter opener) and thrust it toward his chest. A gesture that if not well known, is quite significant.

The founding fathers were for the most part the educated elite of their time and cleaved to romanticized versions of ancient Greece and Rome as well as the virtues of those societies (casually ignoring idol-worship, “flexible” sexual practices, sophisticated torture, institutionalized political bribery and human enslavement). For these individuals, Roman examples of bravery, honor and governance were influential and important. So, when Henry thrust his paper opener at his chest he was recalling a very specific and allegorically important moment in Roman history – the suicide of Cato.

Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (95-46 BCE, also known as Cato the Younger, or just Cato) was a nemesis of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) and his followers, and with others fought against Caesar in the Roman civil war of 49-45 BCE. Cato, a Roman Senator, viewed the war as being fought for representative government (which he favored) versus dictatorship (which he surmised would result from a victory by Caesar). His concerns were objectified, as the victory and subsequent reign of Caesar marked the end of the Roman Republic (the Senate persisted, but as much less of a governing body), and the beginning of the rule of emperors, e.g., The Roman Empire. As Caesar’s troops closed in on Cato’s indefensible position in Utica (on the Mediterranean shore of North Africa in modern-day Tunisia), he had his sword brought to him and committed suicide by stabbing himself in the abdomen.

The importance of Henry’s gesture is it refers to this historical episode - one that explains why he did not utter the words “give me freedom…”, but rather specifically “give me liberty…”. While you may assume these two terms are interchangeable, they are not. Cato and Henry both knew freedom – while the ideal and natural state of man, was impossible to achieve without liberty. The definition and relationship of these two terms were very clear to our country’s founders - freedom being the “right to act, speak or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint”, and liberty, “freedom from arbitrary or oppressive authority”. It’s important to remember “arbitrary” means “based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system”. So if one agrees to these definitions it’s perhaps clear freedom cannot exist without liberty.

Cato committed suicide to avoid experiencing the death of liberty - represented by the representative Roman Republic – and its replacement by the arbitrary rule of an emperor. And Patrick Henry was willing to die rather than subject himself to the arbitrary rule of the British king for the same reasons. They also knew while dictators and despots had the option to avoid oppression but that it was an effective weapon to control others, and without checks and balances it would eventually be employed. So, what is arbitrary authority and why should we agree with Cato and Henry it precludes liberty and makes freedom less likely?

Rational authority (1) employs preconceived guiding principles (e.g. traditions, rules and laws) that would be considered reasonable for most to whom they apply, (2) is willing to limit freedoms, but only when they infringe on the freedoms of others, (3) acts on the behalf of the individuals they lead, rather than for their own personal benefit, and (4) applies preconceived traditions, rules and laws equally to all. Arbitrary authority, on the other hand, is (1) based on random choice or personal whim rather than any reason or system (such as preconceived traditions, rules and laws), (2) may be unfettered by checks and balances and have absolute authority to act as they wish, (3) may act to benefit themselves or groups of interest rather than the general citizenry, and (4) can change traditions, rules and laws without regard to reason and apply them unequally as they wish.

If we can avoid arbitrary authority and promote liberty, whey they can’t our freedoms be boundless? Why did I include in the list of characteristics of rational leaders the ability to “limit freedoms, but only when they impinge on the freedoms of others”? Isn’t that arbitrary? Not at all – it’s absolutely necessary for a free society to function well. As Theophilus Parsons (1750-1813), a young Massachusetts lawyer who would become that state’s supreme court chief justice wrote in the Essex Result, it comes down to which rights are “alienable” (capable of being limited by government) versus those that are “inalienable” (should ideally not be limited):

“All men are born equally free. The rights they possess at their births are equal, and of the same kind. Some of those rights are alienable, and may be parted with for an equivalent. Others are unalienable and inherent, and of that importance, that no equivalent can be received in exchange.’

With the notable exception of the freedom of thought we should not expect our freedoms to be unlimited, as we must find ways to strike the right balance between rights and freedoms for all. What we strive for; therefore, is not the freedom to do or say anything we want, whenever we want no matter the consequences - because freedom unfettered always infringes on the freedoms of others. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) (admittedly a slave owner - so quoted here as more of a “do as I say, not as I did” concept) summed it up well:

“...rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will, within the limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others.”

Let’s take a look at three basic freedoms – the freedom to act, the freedom to speak and the freedom to think.

The Freedom to Act

If we at tacitly agree freedom unfettered always infringes on the freedoms of others, then perhaps we can also agree the most obvious way to infringe on another individual’s rights is by physically acting (or refusing to act) rather than simply speaking or thinking, and as a result this freedom is the most likely target of authority's restrictions.

There has been a long-tenured debate regarding the foundational nature of human beings, as in are we innately good, or innately bad? Throughout history, many have considered this question as well as how it relates to the need for, and form of, governing structures. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke both contemplated and disagreed upon what the likely behaviors of humans in a time before “civilization” they both termed “The State of Nature”. Hobbes viewed man as innately vicious and in need of heavy-handed authoritarian rule, but Locke believed humankind’s innate nature was to seek equality and freedom and this provided for the possibility of a government constituted by many and with the consent of all (ICYMI, our founding fathers chose Locke’s approach over Hobbes’). What both did agree upon; however, was that good or bad we all had the capacity to infringe upon on other’s rights and freedoms in the pursuit of our own and therefore we must have traditions, rules and laws to prevent this when possible.

If someone owns a sports car she may want to drive it 150 mph on the highway, perhaps feeling since she paid handsomely for it and it was designed to be driven fast she should be free to do so. However, this desire to act freely does not pass the test of infringement. Driving at 150 mph puts other’s right to life at risk, and so laws exist to regulate the speed at which we drive. It is reasonable to remind at this juncture most fifth graders also know the right to life (along with liberty and the pursuit of happiness) is spelled out quite explicitly in the United States Constitution as inalienable.

It is often more contentious when we are compelled by authority to do something we might otherwise choose not to do if we were completely free to act or not act as we wish – such as submit to an annual emissions check on that Maserati, or have our child vaccinated for measles. However, both of these pass the infringement test, and should not be considered the arbitrary mandates of authority, but rather the rules of rational authority “considered reasonable for most to whom they apply”. If you pollute the air or refuse to vaccinate your child for measles (1/4 infected are hospitalized and 1-2/1000 die) you infringe on others’ right to life. Of course, the latter example requires you have faith this and other vaccinations (including Covid) are safe and effective - so as a physician and scientist I will take the liberty of saying they are… and move on.

The Freedom To Speak

Most consider the First Amendment right of free speech immutable and essential to democracy. This amendment, ratified initially as part of the first ten amendments to the constitution Bill of Rights in 1791. However, the actual limits of free speech are being questioned and debated vigorously in the moment.

Free speech protections are heavily rooted in the powerful metaphor of the “Marketplace of Ideas”, promoted by Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935) in his 1919 opinion in the Abrams vs. United States Supreme Court free speech case. The concept is market competition will allow, over time, for the truth of any speech to be evident as it is debated and challenged in public discourse. This efficient market concept makes sense to most Americans living in a competitive capitalist system, but it is one that has lost some of its relevance as the founding fathers’ original concepts of how speech would be presented, debated and challenged was a far cry from the present situation. In 1791 the formal press was small, focused on ideas and veracity and public debate and discussion in town meetings and other informal and more formal settings was common. Even as we moved into the 19th and 20th centuries and prior to the age of social media, the voices promoting ideas were few in number and competed on the basis of speed to market, the power of promoted ideas and most important - truth.

Morgan Weiland, Executive Director of the Stanford Law School Constitutional Law Center and Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society, says this model really no longer exists:

“But the marketplace of ideas is a twentieth-century relic. It took root in the context of an expressive ecosystem defined by a handful of homogeneous commercial print and broadcast titans that reflected the views of a narrow and elite slice of the public and sought the aspirational, if unattainable, goals of truth, democratic deliberation, and government accountability facilitated by a press that took those aims as its responsibility.”

Weiland goes on to tell us the metaphor of the “Marketplace of Ideas” has been replaced by “The Free Flow of Information” and there are two critical differences between these two models. First, the business model for the “Market of Ideas” press was to make money by accumulating readers and viewers who trusted them and were impressed by the speed with which they reported the news as well as their efforts to promulgate truth as well as reasoned “ideas” that could be considered and debated. However, the business model of social media news outlets (and ALL news outlets now have a social media component, not just Facebook and X) is now engagement at all costs, and characterization of our individual commercial interests – e.g., understanding which ads and products we are most likely to purchase by keeping us engaged. How are we kept engaged? By information, and lots of it… information indifferent to logic or truth, usually bereft of any tangible ideas and is directed at us by algorithm. Second, where the marketplace put pressure on the press itself to fact check and try its best to discern what was true and what was not before transmitting, all of the impetus is now squarely on us to discern what is true information vs. what is not, and “we” are just not that good at it. Weiland elaborates:

“The (new) metaphor’s logic prioritizes content quantity over quality, privileges information over ideas, removes accountability from the system of expression, and displaces responsibility onto listeners, who are ill-equipped to sort the informational wheat from the chaff. In the end, truth loses out… Today’s expressive ecosystem dramatically departs from the metaphor’s core assumptions, marked by information overload and replete with misinformation and lies proliferated by speech platforms unable or unwilling to act as “arbiters of truth.”

This new model means we will be increasingly bombarded like never before with misinformation, disinformation, half-truths and outright lies at times, and as a result stress will be placed on whether First Amendment protections no longer apply. One test that remains cogent despite the change from “Marketplace” to “Information Flow” is the concept of imminent danger, and that bar has been set appropriately high, as noted by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (18561941) comments in the 1927 Whitney vs. California free speech case:

“Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech and assembly. Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears. To justify suppression of free speech there must be reasonable ground to fear that serious evil will result if free speech is practiced. [And] There must be reasonable ground to believe that the danger apprehended is imminent.”

An example of what we are likely to increasingly see related to the new model of maximizing information flow over vetted truth is the presentation of misinformation about covid vaccines and treatments on social media channels. While some claim this misinformation should be protected by the First Amendment, others (myself included) disagree - despite our desire to protect true First Amendment rights. The danger to our society and to human life was imminent - and thousands of lives were lost as a result of what Facebook Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg has termed laudable “greater expression”expression that led to vaccine hesitancy and unapproved treatments. Let’s be clear, Zuckerberg was not referring to the promotion of substantive ideas to be debated, or the seeking of truth - but rather what Weiland would simply call the “free flow of information”... the truth be damned.

Vincent Blasi, the Corliss Lamont Professor Emeritus of Civil Liberties at Columbia University and a vigorous academic proponent of First Amendment rights, suggested there are several arguments for requiring “imminence” of threat for denying First Amendment protection, including among them (1) remote harm can be refuted over time, (2) time will allow dissipation of energy and will, (3) remote harm can’t really be measured in the present, and (4) so many contingencies can take place to make something harmful or not in the future that it is unpredictable. None of these could be easily applied to the covid social media misinformation situation, and it is easy to see the infringement on the freedoms of others rule was absolutely in effect. By providing me covid misinformation, you put my freedom to life at imminent risk.

The Freedom to Think

Of all the freedoms we aspire to, freedom of thought is the only one I believe worthy of infinite protection, and we should protect mos t assiduously. Virtually all human behaviors (save a handful of reflexes) of action and speech originate in thought, and what we say and do, now and in the future, will determine our fate as a species. However, this freedom is under active attack. I have often told my children (admittedly… usually in a futile attempt to get them to do their homework), “the one thing no one can take away from you is what you learn and what you think as a result”. However, I am increasingly concerned this is a flawed promise.

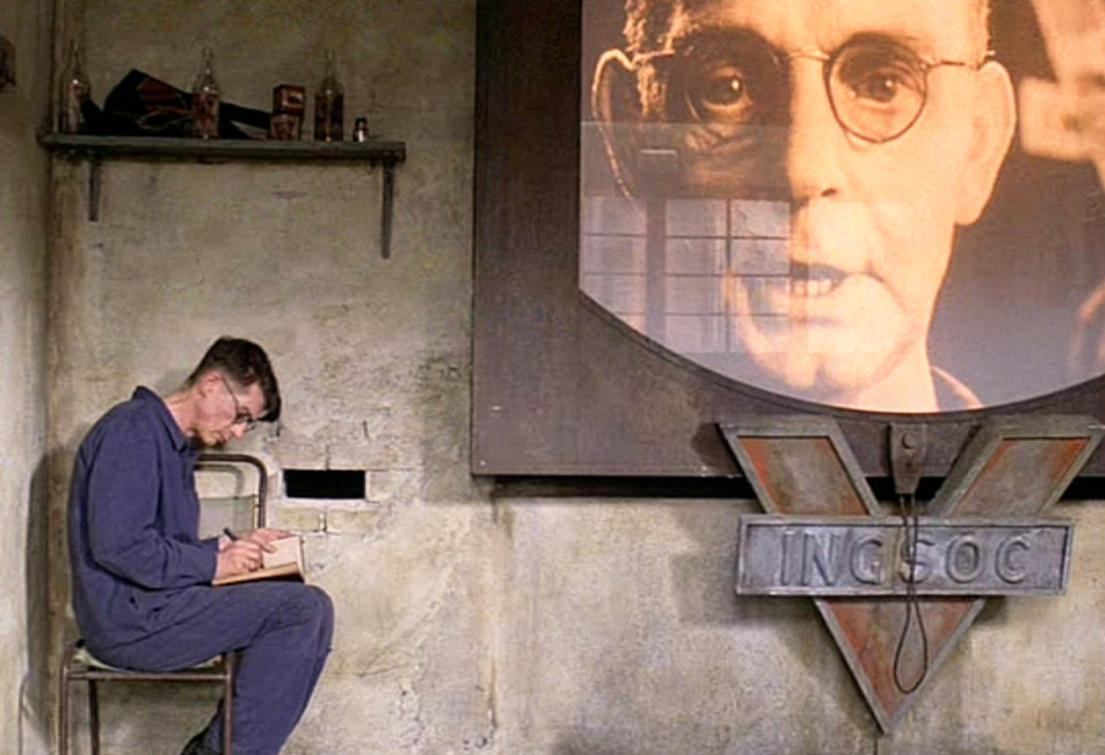

In George Orwell’s 1984, the citizens of Oceania had two-way large television screens in their homes that both continually transmitted propaganda and also surveilled them for any signs of disagreement, and those who did disagreed were re-educated and the use of oft-repeated slogans and the rewriting of history accompanied “Big Brother’s” use of media. Does any of this sound familiar? Modern social media platforms have poured rocket fuel onto the use of propaganda to change the way we think and feel, and among the risks to all human freedoms, this is perhaps the most dangerous. As I and many others have commented, we are increasingly being programmed by commercial interests, political parties and governments to think and feel in ways that benefit them, regardless of costs or benefits to us and artificial intelligence will assuredly make them more effective.

In the quest for freedom of thought the development of mechanisms to ensure the sharing useful ideas and truthful facts, rather than simply “free information flow” directed at getting you to buy something or vote for some political ideologue are desperately needed in place of the current game of hot potato (with frequent drops) between government, fact-checking organizations and media providers. In addition, educational approaches that teach our children and grandchildren how to think critically and to seek truth in information rather than simply accept it if it confirms their biases will be of increasing importance to maintaining a stable, less polarized and functional democracy.

The founding fathers clearly understood the difference between freedom and liberty. When Patrick Henry uttered his famous words in Richmond, he used the word liberty rather than freedom purposefully, and he was not implying “If I can’t do whatever I want to do I would rather die”, but rather, “I would rather die than be subjected to the arbitrary authority of a king”.

While the word “freedom” is mentioned in the United States Constitution one time, and does not appear in the Declaration of Independence at all, the word “liberty” is used three times in the former and is a front and center consideration (one very important time) in the passage describing our three inalienable rights of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” in the latter. I posit the founders also believed while unfettered freedoms always infringe on the freedoms of others and therefore cannot be infinite - liberty could and ideally should be.

While authoritarian regimes may function well for a while – as some seem to be in the present time - historically they all fail, and they do so because by our very nature we choose liberty and freedom and reproducibly reject Hobbes’ characterization of us as well as his authoritarian solution. As Adams suggested, in the present moment, some Americans seem to value “wealth more than liberty”, and some – “the tranquility of blind trusting servitude” to a cult of personality over true freedom. We must choose rational, rather than arbitrary leaders and despite our petty political disagreements we all – republican and democrat, conservative and liberal – must agree to come together to protect and foster liberty. All our freedoms depend on it.