6 minute read

Part A The fundamentals

from Facade Construction Manual

by DETAIL

B 3.2

Advertisement

B 3.3

B 3.4 formwork and powerfully highlight the material of the facade and interior. One building in which concrete was expertly used in the facade’s modelling is the Goetheanum in Dornach (1928) by Rudolf Steiner, although building such plastic, organic designs involves a great deal of work and sophisticated artisanal formwork techniques.

In the 1950s concrete became a mass-market building material, used in all kinds of construction tasks. One main driving force was Le Corbusier, who sought to highlight concrete’s immediate, “raw” materiality – “Béton brut”. He used it skilfully as a design medium in relief and/or plastic facade surfaces, such as the Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tourette priory (1960) in Éveux near Lyon (Fig. B3.2). While Swiss firm Atelier 5 used raw exposed concrete for (small) residential buildings in building the Halen housing estate near Bern (1961), Louis Kahn chose very smooth surfaces for the Jonas Salk Institute in La Jolla (1965). Kahn was also the first to structure concrete facades along orthogonal lines by using shadow joints and carefully positioning formwork ties, making the facades’ production process legible. In the 1960s and 1970s many architects increasingly used the options concrete offered for moulding exterior walls and buildings and the various design possibilities of its surfaces. Unique buildings from this period include the Pilgrimage Cathedral in Neviges (1968) and the Town Hall (Rathaus) in Bensberg (1969) by Gottfried Böhm. These buildings – especially the church – model a plastic, rugged structure with powerful, opaque surfaces whose fine texture of formwork structures prevents them from appearing monotonous (Fig. B3.3). Another very plastic use of concrete as a material is evident in an office building by Barbosa & Guimarães Arquitectos in Porto (2009) (Fig. B 3.5). Here polygonal facade surfaces determine not only the building’s outside appearance but also its interior spaces. While Carlo Scarpa explored concrete’s mouldable qualities in an almost (skilled) craftsmanly manner, especially in the Brion family monument in San Vito d’Altivole near Asolo (1975), Paul Rudolph used industrial textured formwork for the Art and Architecture Building at Yale University in New Haven (1958–64) (Fig. B3.1, p. 107). The fluted profiling of its coloured surfaces, alternating smooth grooves with rough, broken piers, creates a sophisticated play of light and shade. Adding locally available materials to concrete and/or structuring damp surfaces can open up further design options, as Auer+Weber demonstrate in their ESO Hotel at Cerro Paranal (2001) (see p. 123) and Herzog & de Meuron at the “Schaulager” art storage facility in Basel (2003) (Fig. B3.8).

More recently architects have often sought to express the impression of a monolithic construction method, down to the last detail. The avoidance of any construction joints, dispensing with visible formwork ties, and structural components with extremely pared-down cross sections and novel appearances has subjected this high-performance material to enormous technical challenges.

Prefabrication

Producing concrete on a building site has structural and technical disadvantages, so efforts have been made to break structures down into similar, transportable elements that can be serially produced in prefabrication plants. These make it possible to work in any weather and ensure higher quality and greater precision in production and higher standards in surface finishes. The first field factory for precasting concrete elements opened in France in the early 1890s. In 1896 French stonemason François Hennebique made the first building prefabricated in a series, using a transportable cubicle made of 5cm thick, reinforced concrete slabs. From 1920 assembly-based construction methods using steel-reinforced concrete became increasingly important. Architects like Ernst May, who applied a system of wall blocks of various sizes that he developed in a series of housing estates in Frankfurt am Main (Praunheim, 1927), and Walter Gropius, who used a small-format construction method and hollow slag concrete blocks for the Dessau-Törten estate (1927), worked on con-

cepts involving extensive prefabrication. Although these systematic approaches did not become established in construction technology or economy, these experiments were an important (first) step on the path to industrialising building [2]. In the 1950s and 1960s large panel construction – building with large format, load-bearing walls – became widespread. While prefabricated system construction resulted in the building of very schematic facades on a massive scale, postmodern architecture almost reversed this approach, using prefabrication and the plastic malleability of concrete elements to create arbitrary interplays of colours and forms. Architects like Angelo Mangiarotti (see p.116), Bernhard Hermkes (Architecture faculty building at the Technische Universität Berlin, 1968, Fig. B3.4), Gottfried Böhm and Eckhard Gerber formulated architectural responses. Böhm’s administration building for Züblin AG in Stuttgart (1984) shows a sophisticated treatment of the forms and colours of precast elements. Gerber used orthogonal planar steel-reinforced facade elements in a structurally clear way to clad the columns and spandrel panels of an office building in Dortmund (1994). “Heavy-duty prefabrication” is once again an option from a technical and design point of view. Architects such as Thomas von Ballmoos, Bruno Krucker (Stöckenacker housing estate in Zurich, 2002) and Léon Wohlhage Wernik (Sozialverband headquarters in Berlin, 2003) have planned buildings with storey-high, multilayered precast elements that vary slightly in size and create a harmonious result.

B 3.6 One form of unreinforced facade cladding is small-format, concrete artificial stone panels. Panels fixed with mortar are a robust, easilyworked building material that has been used in construction for more than 100 years, especially at the bases of buildings. One of the earliest examples of this in Germany was the Town Hall (Rathaus) in Trossingen (1904), where concrete panels clad the plinth and splayed door jambs. The wide range of ways that concrete can be worked and shaped and the combinations of different aggregates possible have been used to create ornamental structural elements such as (demi-) columns, balusters, gables, rosettes and the like. Concrete panels are now widely used as a suspended, rear-ventilated, small-format cladding material, as in the red facade of the German School in Beijing (2001) by Gerkan Marg+Partner.

Concrete blocks

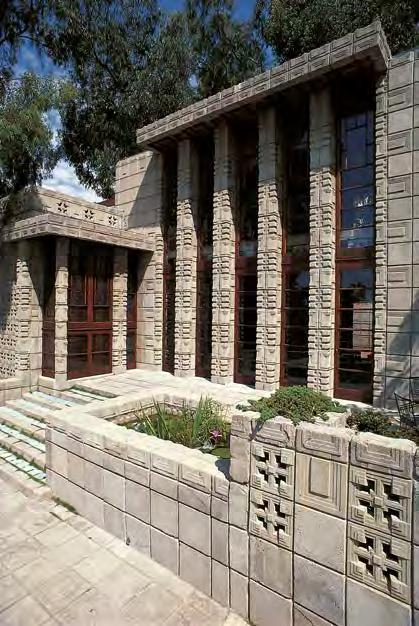

Concrete blocks offer the advantages of en abling small-format, light construction with a wide range of colours and surface treatments. From 1914 Frank Lloyd Wright explored various ways of using them. With his “Textile Block” system, he was seeking an alternative to largeformat panel construction. Starting from a square basic module, he worked with variously shaped bricks and stones. Buildings like his John Storer house in Hollywood (1923) feature richly ornamented facade surfaces with alternating patterns of smooth and structured stones (Fig. B3.6)[3].

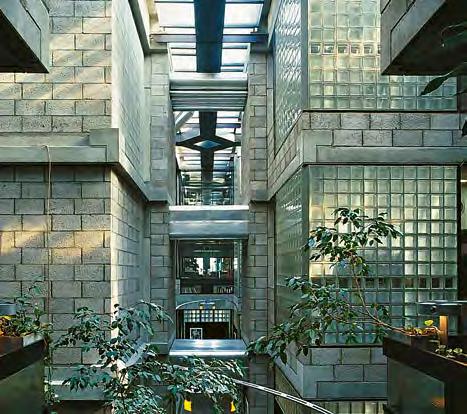

Egon Eiermann focused on the motif of a translucent wall, using concrete grid blocks with (coloured) glass infills in the St Matthew Church in Pforzheim (1956), and the Kaiser-Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin (1963). Another application for exposed masonry blocks is as opaque surface filling in a steelreinforced concrete structure, a technique frequently found in Herman Hertzberger’s work. In buildings such as the Centraal Beheer office building in Apeldoorn (1972, Fig. B3.7), the Vredenburg music centre in Utrecht (1978) and the Apollo Schools in Amsterdam (1983), untreated exposed masonry, visible inside and out, with its the slightly porous surfaces and variously coloured textures, contrasts strikingly with smooth exposed concrete and glass (brick) surfaces [4].

B 3.2 Priory of Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tourette, Éveux (FR) 1960, Le Corbusier B 3.3 Pilgrimage Cathedral, Neviges (DE) 1968, Gottfried Böhm B 3.4 Architecture faculty TU Berlin (DE) 1967, Bernhard Hermkes B 3.5 Vodafone Headquarters, Porto (PT) 2009, Barbosa & Guimarães B 3.6 John Storer House, Hollywood (US) 1924, Frank Lloyd Wright B 3.7 Office building, Centraal Beheer, Apeldoorn (NL) 1972, Herman Hertzberger B 3.8 Schaulager, Basel (CH) 2003, Herzog & de Meuron