6 minute read

There Is Power in Empathy

Light and Health Research Center at Mount Sinai

By Mark S. Rea, PhD

Lighting is installed in buildings to benefit occupants. If there were no occupants, lighting would be unnecessary.

It goes without saying that no one wants to waste electric lighting energy (electric power × duration of operation) when a building space is empty. Not only does the generation of electricity have negative environmental and societal impacts through unnecessary carbon production, but someone also must pay for illuminating a space when it is empty.

Codes are put in place to help ensure that wasted lighting energy is minimized under the assumption that people will forget to turn the lights off when they leave a space and that daylight can reduce the need for electric illumination when the space is occupied. As a result, codes require that automatic lighting control hardware, and usually software, be installed in new construction and renovation under a second assumption that these automatic controls will not have a negative impact on the lighting’s benefits to the occupants.

We have become used to automatic motion sensors and photosensors since the 1970s, when lighting represented about 50% of the energy devoted to commercial building operation and when reducing energy consumption, wasted or not, was a clear societal goal.

In that context, we did not think to question the validity of the two assumptions underlying code requirements for automatic lighting controls. Indeed, we collectively embraced them in our attempts to fight the energy crisis.

And today, because automatic lighting controls are now so common, we do not question the assumptions underlying code requirements.

It’s safe to assume that people will sometimes forget to turn the light off when they leave a space, but it is not always true. The fact is, we don’t really know much about the magnitude of wasted lighting energy due to forgetfulness, although there are some studies showing that manual control of lighting (i.e., remembering to turn the lights off when leaving) can save more energy than relying on automatic lighting controls alone.

But it’s also safe to assume that automatic lighting controls can be so annoying that people will disable them, making their initial purchase unnecessary and limiting future energy savings.

Some may feel that annoying occupants with automatic lighting controls is just something we have to accept in our collective attempt to minimize wasted lighting energy (Figure 1). But in a broader, contemporary economic context where lighting only represents about 10% of the electric load in buildings, we also need to know the cost of occupant annoyance.

This cost is not trivial, as is shown in the accompanying sidebar. The cost comparison in the sidebar relies upon the energy cost to a customer, which probably does not fully capture the environmental cost of energy generation. But at the level of building economics, the cost of annoying an occupant will completely swamp the cost of lighting energy waste due to occupant forgetfulness.

The Cost of Occupant Annoyance

The purpose of most lighting controls is to save energy. Energy savings are obviously an important consideration, but those savings should also be considered in a financial context.

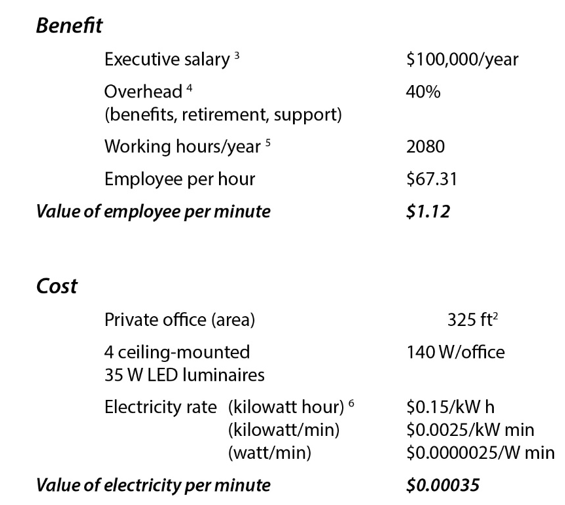

For example, a common problem with motion sensors is the electric lighting turning off while the room is occupied. If turning off the electric lights results in a one-minute loss of productivity by a typical project manager sitting in a windowless private office, this loss in productivity is the financial equivalent of continuously operating the electric lighting in that same office for two days, five hours and twenty-five minutes.

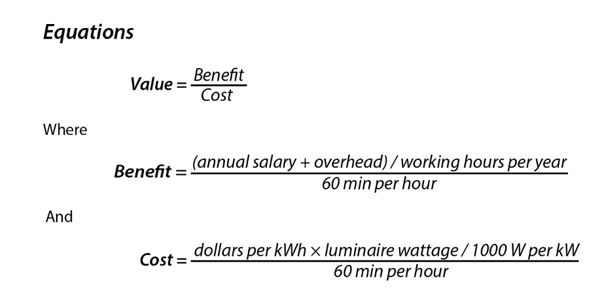

Naturally, the costs of the employee, the overhead, electricity, the size of the office to be illuminated, and number of luminaires controlled by a motion sensor can vary considerably. So the following formulation can help estimate the relative benefit-to-cost ratio, or value, for a given situation where automatic controls aimed at turning lights off might affect productivity.

It's time to revise how we think about lighting controls. Today, we simply begin specifying lighting controls with the energy codes in mind. Given the cost differential illustrated in the sidebar, however, I suggest we begin specifying lighting controls, both automatic and manual, with the occupant in mind and then consider how to meet the energy codes.

Specifiers first need to establish empathy for the occupant, putting themselves in the shoes of the people they are presumably trying to support with lighting. While adopting that empathetic frame of mind, the lighting controls specifier needs to follow six basic steps (adapted from Nordman and colleagues2) when considering the selection of lighting controls.

1. Purpose: Define the benefit to occupants provided by a lighting control (e.g., safety, aesthetics, visual performance, circadian regulation).

2. Approach: Make the lighting control point or override easily accessible (e.g., at the entrance to a space, at the proper height for those in wheelchairs, on the luminaire itself).

3. Interpret: Ensure that the control point or override is intuitively linked to the lighting it controls (e.g., adjacent to the luminaire or on the luminaire itself).

4. Interact: Choose the control point or override that is easy and obvious to operate (e.g., toggle switch or slider dimmer).

5. Feedback: Ensure that an initiated operation of the lighting control point has an immediate, perceived effect (e.g., the room lighting status change can be seen or tactile stimulation can be felt).

6. Caution: Ensure that an unanticipated change in lighting status can be perceived and understood by the occupant before the lighting status actually changes (e.g., modulating the lighting level or auditory warning signal) so that the previous five steps can be completed.

These six “empathetic” steps should be completed, and I suggest professionally documented, when specifying both manual and automatic lighting controls. If the building occupants understand the purpose of the manual or the automatic lighting controls and they know how to affect the status of the lighting with an obvious and easily operated control point, either through initiation or override, their productivity will not be unnecessarily compromised. Moreover, because occupants will no longer permanently disable the lighting control, more lighting energy will be saved.

References

1. Maniccia D, Rutledge B, Rea MS, Morrow W. Occupant Use of Manual Lighting Controls in Private Offices. Journal of the Illuminating Engineering Society 1999;28(2):42-56.

2. Nordman B, Granderson J, Meier A, Papamichael K, Cunningham K, Wu K. Lighting Controls User Interface Standards. Davis, CA: California Lighting Technology Center, Lawrence Berkely National Laboratory. 2010. Report No. PON-08-002.

3. Forage. 10 Jobs That Pay $100K a Year. San Francisco, CA: Forage. 2023.

4. Connecteam. How to Calculate the Real Cost of an Employee. New York: Connecteam, 2023.

5. Mulroy C. How Many Work Hours in a Year? We counted the days and crunched the numbers. McLean, Va: USA Today. 4 January 2024.

6. Shrink That Footprint. Commercial Vs Residential Electricity Rates Across the US – 2024. Petersfield, UK: Shrink That Footprint. 2024.