48 minute read

INTRODUCTION

The City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services (DBHIDS) is proud to offer behavioral health care, intellectual disability supports, and early intervention services in one comprehensive integrated system.

The mission of DBHIDS is to educate, strengthen, and serve individuals and communities so that all Philadelphians can thrive.

We envision a Philadelphia where every individual can achieve health, well-being, and self-determination.

Our services are offered through a network of provider agencies. We also collaborate with the Philadelphia School District, the child welfare and judicial systems, and other stakeholders. It is through our many partnerships that we can serve Philadelphians who need our help and support.

DBHIDS serves all Philadelphians as evidenced by our longstanding commitment to recovery, resilience, and self-determination. Traditionally, we have prioritized services to individuals who are experiencing a mental health or substance use-related condition or intellectual disability to improve their outcomes.

While that focus remains, today, we are also intensively aware of the needs facing all in the community –those in need of behavioral health treatment and those who strive for behavioral wellness. We take an active role in promoting the health and wellness of all Philadelphians through our population health approach and through our priority lens TEC by addressing Trauma, achieving Equity, and engaging Community.

This report provides an overview of DBHIDS’ TEC programs and strategies that are operating and those we plan to implement over the next one to three years. Our strategies include immediate actions that will address pressing issues as well as longer-term strategies to address trauma, achieve equity, and engage community as we seek to transform our system.

Population Health Approach

Philadelphia has a population of 1.57 million people, of which 750,000 are Medicaid eligible. By applying a population health approach, DBHIDS is seeking to improve the health of all Philadelphians, including the approximately183,000 individuals we serve annually.

Our approach includes

1. Working upstream (earlier intervention)

2. Broad set of strategies

3. Working with at-risk and healthy populations

4. Delivering health promotion interventions

5. Working in non-treatment settings

6. Health activation approaches empowering others

7. Working at the community level

8. Wellness for all

9. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

10. Developing innovative community partnerships

Through Medicaid and County dollars, we can provide support to low income, under-insured and uninsured residents. People are able to access DBHIDS services in a variety of ways, which is reflects our outreach and engagement efforts as well as lessons learned from communities and stakeholders. The “front-doors” of our system include:

1. 988/ Philadelphia Crisis Line

2. WarmLine (Operated by people with lived experience and clergy)

3. Community Behavioral Health Member Services

4. Network of Neighbors

5. Crisis Response Centers

6. EPIC – Ask for it by name

7. Community Outreach Events

8. In-Community Behavioral Health Screening Events

9. Boost Your Mood

10. Provider Network

11. Health Minds Philly

12. Outreach and Engagement Teams

13. Schools

14. Mental Health First Aid

15. Targeted Engagement (Engaging Males Of Color and Immigrant Refugee Wellness Academy)

16. Intellectual disAbility Services

TEC AND P.A.C.E.

The TEC lens layers on top of the DBHIDS Strategic Plan P.A.C.E. (Prioritizing to Address a Changing Environment). The P.A.C.E Framework has five priority areas along with corresponding goals and key performance indicators that include (see appendix 1):

1. Prevention and Early Intervention – further develop services around community needs.

2. Treatment and Services – increase access to services

3. Health Economics – improve processes and practices to enhance cost effectiveness

4. Infrastructure and Intelligence – increase the use of business analytics and information flow to inform service delivery and improve outcomes

5. Innovation – innovate to improve programs, processes, and efficiency.

Tec Vision

Below outlines the TEC lens. DBHIDS seeks to transform existing systems by shifting processes and practices based on the following lens:

1. Addressing Trauma means creating a system that is trauma-responsive, trauma-informed, and trauma-mitigating. DBHIDS recognizes institutional trauma as a type of systemic trauma that can result from institutional action and inaction. With TEC, DBHIDS is addressing various types of traumas, including institutional harm, by creating programs that aim to ameliorate the risk of institutional wrongdoing.

Charge: a. Reduce traumatic experiences in the system b. Change processes to be trauma responsive and trauma mitigating c. Shift systems to be trauma reducing

2. Achieving Equity requires DBHIDS to intentionally identify and address institutional and structural racism, transform systems to reduce behavioral health disparities, and promote racial equity for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). The DBHIDS Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) unit is constantly working to inform programs and processes to promote equity within the Department and externally.

Charge: a. Identify and change processes that create disparities b. Review/evolve hiring, contracting, and community engagement processes and practices to reduce disparities.

3. Engaging Community encourages DBHIDS to connect individuals to community-based services and integrate community wisdom into program development and operations. DBHIDS recognizes the importance and effectiveness of fully integrating programs into the community and is working actively to shift its programs in this direction as much as possible. DBHIDS also wants communities to have a voice in program development as a way of ensuring successful implementation of communitybased programs.

Charge:

1. Shift Services from institutions to community settings

System Transformation

Using a TEC lens to shift system responses that add a layer of trauma to those that mitigate against trauma by shifting processes and practices

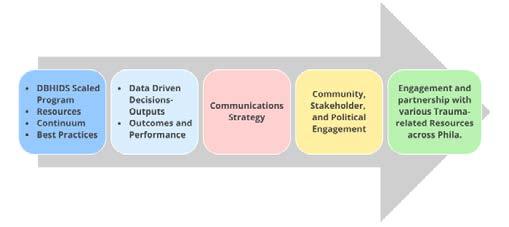

Tec Strategies

Our TEC vision is implemented through a range of strategies, supporting the vision. The strategies have evolved over time, to be responsive to needs as they have emerged. The strategies include:

1. Addressing Trauma – Blanketing the city Trauma Supports a. Individual Interventions b. Community-based Interventions c. Website Resources d. Trainings e. Communications strategies (hard copy materials, radio, TV, film, social media, podcasts) f. Hospital-based Programs g. Stakeholder Committees to develop and support trauma strategies h. Implementation of the trauma stakeholder committee workplan i. Trained Community Responders to respond to traumatic incidents in their communities

2. Achieving Equity – Reduce Disparities and Promote Racial Equity a. Conscientious Contracting b. Data Driven programming c. Scaling/expansion of programs to ensure services are available to every community d. Monitoring tools that track data points that identify and address disparities e. *Include language below on DEI

3. Engaging Communities – Increase Community-based Programming and Input a. TEC Talks and Community Conversations b. DBHIDS Conferences - TEC Conference, Faith and Spiritual Affairs Conference c. TEC Tour d. Providing resources at community events e. Public facing websites – DBHIDS.org, CBHPhilly.org and Healthy Minds Philly f. Committees that include community-based organizations and community members g. Developing more community-based programs

The Big Picture

Tec Initiatives

Below are a few of the programs that illustrate the types of initiatives under each category for context. A listing of all the programs across the department organized by TEC category can be found in the PACE/TEC Crosswalk.

1. Addressing Trauma – Blanketing the city with Trauma supports (more than 40 programs). The programs highlighted in “Blanketing the City with Trauma Supports” are built on the importance of community connectedness and shifts access to services and resources to meet people where they are - in their communities. These programs help to connect individuals and communities to the vast array of services provided by DBHIDS, as well as connecting people further to the providers within the behavioral health and intellectual disability networks.

a. Network of Neighbors (expanded in 2022) b. Engaging Males of Color – Trigger Film (2022) c. Community Wellness and Engagement Unit d. ReCAST (launched in 2022) e. Faith and Spiritual Affairs f. Healing Hurt People g. Behavioral Health Crisis System transformation and launch 988 (2022) h. Porch Light Initiative/Mural Arts i. Trauma External Stakeholder Learning Collaborative (launched in 2022)

2. Achieving Equity – Reduce disparities and promote racial equity (more than 30 programs) a. Social Determinants of Health Equity Unit (launched in 2022) b. Forensic Equity Unit (launched in 2023) c. Mobile Outreach and Response Services expansion d. Mobile Methadone Maintenance Treatment (2023) e. Peer Institute f. Alternatives to Detention g. Stepping Up Initiative h. Forensic Support Team i. Immigrant and Refugee Wellness Academy (launched 2022) j. START (launched in 2022)

3. Engaging Community (more than 20+ programs) a. TEC Talks (launched in 2021) b. TEC Talk Community Conversations (launched in 2022) c. TEC Conference (held in 2023) d. TEC Tour (scheduled for 2023) e. TEC Podcasts (scheduled for 2023) f. Faith and Spiritual Affairs Conference (held in 2023) g. NAMI Faith WarmLine h. Community Affairs Unit – Community Wellness and Engagement i. Peer Culture Transformation Advisory Board j. Philadelphia Systems of Care communities k. Healthy Minds Philly l. Family Member Committee m. Youth Move Philadelphia n. Suicide Prevention Task Force

Healing Occurs in the Community: Blanketing the City with Trauma Supports

DBHIDS is committed to bringing services to individuals and communities across the City. The services listed below show the shift in service delivery from provider and clinical settings to include community spaces that meet people where they are. These models demonstrate the need for a variety of engagement approaches to make services available to all Philadelphians.

Network of Neighbors Expansion

Regional Team Model Expansion of the Network of Neighbors staff will include four teams working across four regions of the city, along with administrative staff to support the overall operations of the program

Engaging Males of Color Initiative

2021 EMOC focused on the traumatic of impact social justice issues on males of Color

Community Wellness Engagement Unit

Designed to provide greater access to Behavioral Health support, guidance, and linkages to care on a community level

• Peer Culture and Community Inclusion – those with lived experiences engaging the peer community and the integration of those with lived experience across the continuum

Mural Arts

Themed Murals: Trauma and Healing

External Stakeholder Group

To leverage services, resources, expertise, and wisdom from key community-based organizations, providers, people with lived experience, academicians, stakeholders from all corners of the community

Faith and Spiritual Affairs

Trauma and healing from a faith-based perspective

Addressing Trauma

Trauma Overview

Trauma is an emotional experience to a terrible event or series of events that could have occurred once or multiple times over an extended period. Trauma poses a significant threat to the overall health and wellbeing of individuals, families, and communities. First responders, health care workers, and counselors are also at risk and may experience vicarious trauma in their efforts to provide supports.

We know that people who experience traumatic events have an increased risk of developing a range of chronic physical and behavioral health concerns, and children are particularly vulnerable. Trauma can impact anyone, regardless of socio-economic status. However, many people in poverty routinely witness violence in their communities and experience various forms of discrimination that exert a toll on their health.

To address trauma, DBHIDS administers programming, maintains and develops partnerships, and implements evidence-based practices and innovative approaches to address the effects of trauma in the City of Philadelphia.

Trauma In Philadelphia

Philadelphia has the third highest poverty rate in the U.S. at 23 percent. This is down from 25 percent in recent years, but unfortunately has continued to sustain at 37.3 percent poverty rate for children. Poverty in and of itself is traumatic. We know that food insecurity, housing insecurity, and lack of basic needs, also referred to as the Social Determinants of Health, impacts one’s health and life expectancy (Healthy People 2030).

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood. ACEs can include violence, abuse, and growing up in a family with mental health or substance use problems. ACEs are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood. Previous studies on ACE’s in Philadelphia have shown that half of Philadelphia’s zip codes have more than 30 percent of children experiencing 4+ ACE scores.

The prevalence of gun violence has been devastating for individuals, families, and communities across Philadelphia, particularly for Black men. As of April 2023, there have been 134 homicides in Philadelphia due to gun violence. While that number is down 14 percent from 2022, it is still 134 lives, families, and communities impacted. Of those killings, 94 percent were Black men. Chronic exposure to gun violence is traumatic, and there is a relationship between trauma exposure and negative mental health experiences. Higher rates of community violence are concentrated in areas impacted by long-term systemic racism and disinvestment, which disproportionately impacts low-income communities of color. Strategies addressing the confluence of chronic exposure to gun violence, community violence, poverty, and trauma are needed. We believe that by increasing community and trauma supports for “at-risk” individuals through prevention, intervention, and postvention in support of a wholistic, citywide effort, we can disrupt the cycle of gun violence. Below shows the total shooting victims and shooting fatalities from 2015-2022.

With these grim statistics, we have engaged stakeholders and examined our existing programming to discuss how DBHIDS can increase and target trauma resources and supports for prevention, intervention, and postvention programming to reduce the negative outcomes of trauma in highly impacted communities.

Vision And Approach To Addressing Trauma

Our vision is to ensure that there is an accessible continuum of services that addresses the various types and stages of trauma for all Philadelphians. DBHIDS will accomplish this through a diverse and effective network of supports programs that address the variety of challenges communities face regarding social economic status, race, or gender.

The framework for this approach features the following steps:

1. Understand existing and needed resources, utilize best practices, and make data-driven decisions.

2. Deepen our work with stakeholders to ensure equitable access to resources and to bring solutions from and sustain solutions in communities.

3. Recognize the impact of traumas associated with many factors including isolation, violence, racism, substance use, the pandemic, etc.

4. Recognize the resources – in-school prevention, supports and treatment, evidence-based models in the continuum, community outreach, support, and engagement.

5. Enact a comprehensive strategy to support people and communities across the city experiencing a variety of traumatic events or circumstances. Within this, the Department has created a landscape review, gaps analysis, communications plan, and stakeholder committees to address specific areas of trauma.

Trauma Challenges

To approach addressing the varying traumas people experience, we created categories to frame our thinking and to begin to identify what services already exist in our system and services that need to be developed. Below includes some of the main categories of trauma identified by our workgroups. Many are related to the COVID-19 pandemic and others are persistent over time. They include:

1. Disruption to behavioral health and physical health services due to the pandemic

2. Pandemic relate illness, death, and isolation

3. Pandemic related emotional and physical disturbance

4. Prolonged and complex trauma

5. Systemic, generational, and direct experiences of racism

6. Political and social unrest

7. Personal and community experiences of violence

8. Poverty: housing, economic, and food insecurity

Current Trauma Programming

DBHIDS funds programs serving adults and youth across five main categories: individuals, communities, website/media, trainings and hospital-based programs. Highlighted below are some of our most visible programs. A full listing of all of the trauma programs can be found in the P.A.C.E. and TEC crosswalk and on public facing web page dbhids.org/trauma which list all of the department’s resources available to the general public.

1. Individual-level Interventions a. Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (serves youth) - designed to help children, adolescents and their parents to overcome the negative effects of traumatic life events. b. Prolonged Exposure Therapy (serves adults) - aims to reduce post-traumatic stress (PTSD) symptoms by helping individuals approach traumatic related thoughts feelings and situations that had previously been avoided. c. Intensive Behavioral Health Services (serves youth) - wrap around services for children in their homes, schools and communities d. Philadelphia Crisis Line – 988 (serves all) - 24/7 crisis line to assist people and their families with behavioral health crisis. e. Crisis Intervention Response Teams (serves adults) - Co-responder model with the Philadelphia Police Department to respond to behavioral health crisis related calls f. Community Mobile Crisis Response Team (serves all) - 24/7 regional response teams that engage, screen, assess, and provide resolution focused crisis interventions. g. Mobile Outreach and Recovery Services (serves adults) - serves individuals seeking treatment for behavioral health services in communities deemed high risk for substance misuse and overdose. h. Student Assistance Program (serves youth) - behavioral health assessment available in all public, parochial and charter schools to ensure students behavioral health needs that may impact their school performance are addressed i. Signs of Suicide Intervention and Prevention (serves youth) - educates youth on signs related to suicide. j. COPE2Thrive offers three Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-based (CBT) programs designed to help children, teens, young adults, and adults dealing with anxiety, stress and depression by teaching them how to develop the skills needed to stop negative thoughts and start thinking and behaving in more positive ways. COPE2Thrive offers nonclinical approaches to help shift the youth’s mindset to reduce or minimize the probability of them using drugs or alcohol to cope with trauma or violence they encounter daily. k. Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Trauma Screener (serves all)– screens disable individuals for trauma l. Crisis Response Centers (serves all) - operates 24/7 on emergency basis for screenings and placement/linkage to appropriate levels of care and services m. Urgent Care – PATH UCC for children (serves children) - serves youth experiencing behavioral health challenges n. Social Drivers of Health Programming (serves all) – mitigates the trauma of poverty by providing food, transportation, technology, employment, housing

2. Community-level Interventions a. Network of Neighbors (serves youth 9+ adults) - provides trauma supports to any community across the city that has experienced a traumatic event. Communities can be defined by, but not limited to geography, schools, churches, places of work, etc. b. Porch Light/Mural Arts (serves all) initiative that creates public murals that seek to transform neighborhoods and promote the health of neighborhood residents and individuals who help create the mural. c. Engaging Males of Color (serves all) - organizes events to engage men and boys of color in dialogs designed to address the impact of trauma, health, economic, and educational disparities. d. Diversity Equity and Inclusion Healing Spaces (serves all) - safe, supportive spaces for discussions to help people process traumatic events with others. e. Peer Culture and Community Inclusion (serves adults) - supports efforts to engage people with lived experience of mental health challenges and/or substance use disorder. f. Community Wellness Engagement Unit (serves adults) - regionalized teams that provide services across the city to community members by linking them with community resources and supports addressing behavioral health wellness and trauma. g. Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Planning Initiative (serves adults) - an integrated system of care for individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders and intellectual disabilities which includes implementation of the START model (START Model is a communitybased crisis intervention for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and mental health needs. The model is evidence informed, person-centered, solutions-focused approach that employs positive psychology and other evidence-based practices. START Stands for Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment, Resources, and Treatment) h. Philadelphia System of Care (serves youth) - resource network for youth and their families to access behavioral health support and trauma related services to support youth experiencing significant emotional and behavioral health challenges impacting them in their school, home and communities. i. Resilience in Communities after Street Trauma Grant- ReCAST (serves youth and young adults)addresses the impact of stress and trauma on youth/young adults and their families caused by community violence, particularly gun violence, by linking them to trauma-informed services and supports, and to reduce violence by and against youth/young adults by implementing evidencebased prevention programs and supporting positive youth and family programming in six specific neighborhoods using a collaborative community and city participatory process

3. Systems Connectors a. Website/Media i. Film- Invisible Opioids (serves adults) - film educating the community on what opioids are and dispelling misconceptions in the black community. ii. Film – TRIGGER (serves adults) - film about gun violence in Philadelphia from multiple perspectives including the shooters, victims, and their families, and more broadly, about healing from trauma. iii. MindPHLtogether.com (serves all) - collaboration between the City and Blue Cross Blue shield to improve mental health. iv. Boost Your Mood (serves all) - campaign to acknowledge stress caused by the pandemic, violence and racism that all cause trauma. v. Health Minds Philly (serves all) - offers wellness tools designed to support mental health and well-being for all Philadelphians regardless of insurance or income. vi. Behavioral Health Screenings (serves all) - Online and in-person screenings to learn whether a person may be experiencing symptoms of a mental health disorder. b. Trainings and Conferences i. Trauma Awareness Trainings (serves adults) - training for providers that discuss various types of traumas and supports providers with implementing trauma informed practices ii. BHTEN Trauma Training Series (serves adults) - trainings for providers, addressing trauma that include the trauma resilience series ranging from interventions, to secondary traumatic stress, psychological first aid and understanding racial, social, and intergenerational trauma. iii. ReCast Provider Trainings (serves youth and adult) - expands culturally competent, trauma informed behavioral health practices in schools and community youth programs through training in evidence-based practices designed, such as PLAAY (Preventing Long Term Anger and Aggression in Youth) iv. Mental Health First Aid (serves youth 16+, adults) - eight-hour course that teaches skills needed to identify, understand, and respond to signs of behavioral health challenges or crisis. v. Crisis Intervention Trainings (serves all) - coordinated effort between the Philadelphia Police Department and DBHIDS to promote empathy and understanding while increasing effective communication with community members when they are in very vulnerable situations. vi. Faith-based and Spiritual Affairs Conference (serves all) –is hosted annually and on April 28, the theme was “Healing from the Hurt with Trauma Informed Care.” Attended by faith leaders, providers, community-based organizations, and members from across the city to learn about resources and tools available to address trauma. vii. Addressing Trauma, Achieving Equity, Engaging Community Conference (serves all) - held on March 24, the theme was “Trauma, Equity and Community in the City of Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection.” Attended in-person and virtually by 400-plus people including providers, community-based organizations, and member to learn about the city’s trauma supports that “blanket the city,” the importance of BIPOC therapists and culturally competent care, addressing trauma experienced by people with intellectual disabilities, secondary traumatic stress, and additional topics. c. Hospital-based Programs i. Cure Violence Philadelphia (serves all) - violence intervention program utilizing a Chicago-based public health model focusing efforts to stop shootings and murders in North Philadelphia. ii. Healing Hurt People (serves all) - trauma-informed, hospital-based violence intervention program that offers case management and linkages to referrals for people who have been victims of violence. iii. Warm Hand Off Program - program operating in area hospitals and emergency department, utilizing peers to connect people to treatment services upon discharge.

Impacts Of Trauma On Children

We know people who experience traumatic events have an increased risk of developing a range of behavioral health concerns, and children are particularly vulnerable. Child traumatic stress occurs when children and adolescents are exposed to traumatic events or situations (school or neighborhood violence; domestic violence; physical abuse; sexual abuse; neglect; serious accidents; sudden or violent death of a loved one, natural disasters, terrorists’ attacks, and war).

Traumatic experiences suffered in childhood can alter the production of neurotransmitters and hormones, which can lead to mood disorders, inability to regulate stress, and an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Symptoms of trauma in children include nightmares and trouble sleeping; avoidance of thoughts, feelings, reminders of the trauma; bed-wetting; attention problems; anger, irritability, temper tantrums, and aggressive behavior; flashbacks and intrusive thoughts of the traumatic event; withdrawal, dissociation (feeling of detachment), and numbness; sadness; loss of trust in others; increased risk-taking behaviors; and poor school performance.

We have also seen more acute presentations of mental illness in children due to the social isolation from the pandemic causing limited access to services. Our goal is to continue and increase resources that children need through our continuum of care.

The diagram below lists services for children and families including individual and community-based interventions.

Services For Children And Families

Below are services for children ages K-12, beginning with prevention services, through individual and community-based interventions

Included in the below diagram is a mapping of the Continuum of Child and Adolescent services for children from infancy, through young adulthood and ranging from prevention to acute services.

CONTINUUM OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT SERVICES

Adolescence

Young Adult (18-21st birthday)

Prevention

Community Treatment Supports

Natural and Community Based Supports, Prevention programs via DHS/DBH/OVR/OAS/IDS/Courts/School District

Case Management (BCM, COC)

HiFi Wrap Assessment

Crisis Assessment

Outpatient Assessment Access Centers

Provider Based Assessments (Psychiatric, Psychological, Master’s Level, FBA/skills)

Children’s Mobile Crisis Teams (CMCT)

Crisis Intervention

Community Based Child and Family Treatment Services

Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment

Residential Services

Acute Services

Crisis Mobile Intervention Service (CMIS)

Crisis Stabilization Units

Outpatient Treatment (Individual, Family, Group)

Intensive Behavioral Health Services (IBHS)- Individual and Group Services (BC, MT, BHT, Group MT, CTSS)

IBHS Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

Early Childhood Treatment Program

Long Term Partial Family Services (FBS, FFT, MST-PSB, PHIICAPS)

Outpatient

Intensive Outpatient Treatment

Short and Long Term Residential

Community Residential Rehabilitation- Host Home Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility

Adult Residential Treatment Facility

Acute Partial Hospital

Acute Inpatient Hospital

Gap Analysis

DBHIDS conducted a gaps analysis and received feedback from DBHIDS staff and the Prolonged Trauma and Children and Families Trauma subcommittees to identify some of the areas of opportunity to increase services and/or resources in our current system. Some of the topic areas that guided our discussion included:

1. Geographic distribution of services

2. Equitable access to services based on population, including: age, race, gender, immigrant and refugee status, intellectual disability, etc.

3. Community-level engagement and inclusion program input and feedback

4. Quality and quantity of services along the continuum: prevention, early intervention, treatment, postvention, policy

5. Diversity of community partners engaged in our work

6. Zip codes not served vs. not served proportionate to needs

Below are some of the gaps identified and recommendations that were proposed:

General Recommendations

1. Trauma-informed approaches need to be developed to serve the intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD) population more effectively. The system needs training and education for staff to ensure staff are able to communicate and serve people with ID and, in particular, non-verbal individuals

2. There should be a due diligence checklist to ensure all special populations are considered when creating new programs/services. Ensure all programs are accessible and available, as applicable to: a. LGBTQIA+ b. Veterans c. Seniors d. People with physical disabilities e. Reentering f. Immigrant populations g. Incarcerated individuals h. Children in child welfare or out-of-home placement.

3. City partnerships could be further enhanced to promote health equity and justice related to trauma. Partner with PDPH on campaigns to educate the public about trauma and the impacts on health. Leverage health systems through collaboratives such as COACH reach deeper into communities to promote available services to address trauma.

4. There are not enough BIPOC and/or culturally competent providers, providing trauma services to BIPOC communities. Connect with BIPOC providers to better serve BIPOC communities. Connect with community-based organizations such as HIAS Pennsylvania and the Nationalities Services Center to better serve immigrant and refugee communities.

5. There is a significant shortage of trauma specialists, trained clinicians, and general behavioral workforce staff. This is causing tremendous strain on the existing systems, decreasing capacity of programs and increasing burnout of existing staff. Need to address behavioral health workforce staffing challenges. a. Ensure all zip codes with children who have an average of 4+ ACES, have access to all our main resources. b. Create a community resource asset map to assist in locating services in areas with high needs. c. Build protective factors and resiliency resources in zip codes with high ACE

6. DBHIDS should consider using Philly ACEs scores as one of the metrics to locate programming.

7. Secondary trauma support is needed for supervisors who are working with and supporting front line clinicians. Create programming that is regularly made available to support staff

8. Some effective trauma programs and intervention are not considered treatment – and therefore are not billable – but should be funded as a part of the trauma services continuum. Set aside funding for trauma interventions that are not Medicaid billable.

9. There is no chat feature or interactive feature on the DBHIDS website. A chat feature or chatbot would be helpful in navigating the site’s services.

10. The public as well as providers are not clear on all the trauma resources available through DBHIDS. Host annual conferences for providers to understand how to access all DBHIDS services including how to refer to trauma resources.

11. Include a link to DBHIDS trauma resource and 988 on all phila.gov pages

Program-specific Gaps and Recommendations

1. Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy - expand to unserved areas, i.e. West Philadelphia. Explore use in addressing racial trauma and cultural competence.

2. Youth Mental Health First Aid – expand training in schools and Out of School Time programs

3. Boost Your Mood- help with navigation. Find additional ways to distribute this resource for people that do not have internet access

4. Behavioral Health screenings - not accessible at all literacy levels. Adapt the screening to be more accessible.

5. Need trauma resources for early childhood care providers for children ages five and younger. Need for immediate response to daycare and pre-k programs in events where young child or class is exposed to or experiences a traumatic event.

6. Need trauma training for children’s mobile crisis teams.

7. Expand language access to include all refugee populations

8. Need early intervention screening: bridging the gaps between non-early intervention substance abuse programs or PACTS providers and OAS services

9. Early Intervention or Substance Abuse Services-providers need access to trauma training

10. Need to work with The Philadelphia Department of Human Services to better address trauma experienced when a child is removed from their home.

Additional Feedback from the Gaps Analysis Discussions

1. The system needs to clearly define the word “equity” so a shared understanding is used to evaluate how services are distributed, managed, awarded, and accessed.

2. There needs to be a real conversation about those that have privilege/power and making room for people that do not have privilege/power to have a voice in creating and implementing services.

3. Include community members and community driven data in program design/development

4. Understand why some programs do well “on paper,” but are not programs that are “trusted” by the people that they serve. Understand if this is only an issue of cultural competency or other factors. Need additional or alternate evaluations to identify this challenge.

5. Larger and well-resourced organizations are better positioned to obtain additional funding. Smaller organizations that may be very effective may not have funding for evaluation and research and this decreases their potential to increase their capacity. Technical assistance and support should be provided to increase equity in awarding contracts to smaller organizations.

6. Ensure programs have trauma-reducing policies. Ensure that programs don’t “exit” people from programming with harsh disciplinary policies but instead are designed to keep people included and set up for success.

7. Fund programs that seek to “interrupt” the cycles of violence and serve the whole family, such as interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline. Serve the whole family and teach the family how to advocate for their family members and themselves.

8. Peer voices should always be included at the development level of any program.

9. Address survivorship bias. We can’t just look at people who’ve been successful in programs. We need to also look at people who weren’t successful and what about those programs/policies that did not work.

10. Understand how different systems work with each other to see the intersections that can or currently cause trauma. Overly stressed and siloed systems hide issues and practices that may cause trauma. Need to focus more on institutional coordination.

11. There is a bridge between academia and practice of about 10-14 years. We need to figure out how to more quickly apply research to practice.

12. Institute modular approaches to therapy interventions for faster results, i.e., MATCH-ADTC – Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma or Conduct problems.

Trauma Metrics

Metrics are tracked on every trauma initiative. These metrics vary based on the program with regard to number of people served, number of community events, program type, etc. In addition to tracking outputs, DBHIDS seeks to track outcomes, demonstrating the effectiveness of each of the programs administered, as well as track trends over time and overlay public data sources to increase our ability to make data driven decisions.

The current data we collect on each program as applicable includes:

1. Number of people served

2. Number of events/sessions/trainings/responses

3. Number of events per zip code

4. Number of participants served per zip code

5. Number of website visits

6. Annual program cost/costs per participant and trends month over month/year over year

7. Utilization rates

8. Recidivism rates

9. Zip codes NOT served

10. Where people live that are receiving a particular service/where people are receiving services

We are currently able to overlay our program data with following public data sources:

1. Police data – shooting, homicides, arrests

2. Percent of people living in poverty in each zip code

3. Percent of Medicaid eligible individuals per zip code

4. Percent of suicides

5. Hunger rate per zip code

6. Literacy rate per zip code

7. Overdose deaths

8. Hospital sites

9. Health centers

10. Crisis Response Centers

11. Schools

2022 Data Driven Efforts Shootings And Network Of Neighbors Responses

Below is an example of a data overlay that we are using to understand how our presence corresponds with activities in communities. Below shows Network of Neighbors responses in green triangles, per zip code, overlaid with the number of shootings per zip code, which are color coded and numbered. This type of data will help to inform our strategies around resources needed and deployed.

Significant Incident Response Model

DBHIDS is often engaged by external stakeholders and the community to provide mental health support after a traumatic event. Events such as the Fairmount fire in 2022 and the Roxborough High School shooting later that year are examples of incidents that posed significant trauma to those directly involved. To respond to external requests from the community at large for various supports and resources in the instance of serious incidences, DBHIDS has created an Incident Response Flow Chart of how requests are triaged to ensure a timely and effective response to community needs.

The purpose of the protocol is to create a clear outline to access department wide resources by external stakeholders. Below are the Stages of the Incident Response Flow. (Appendix B)

Stage 1 - Post Trauma Impact and Needs Assessment

a. Description

Post-Trauma Impact and Needs Assessment is the first phase of the Post-Traumatic Stress Management (PTSM) continuum of trauma and evidence-informed, population, and public health community interventions, and thus communities an intervention on its own. The Post-Trauma Impact and Needs Assessment is coordinated by Network of Neighbors staff and implemented by the impacted community’s natural leadership (Community Connectors) and continues throughout the duration of the response. Since the Impact and Needs Assessment is a joint effort between Network of Neighbors staff, systems partners, and the impacted community’s leadership, at least one community point-of-contact (Community Connector) must be identified prior to beginning the process. It should be noted that the Network of Neighbors’ incident response process occurs separately for each impacted community that makes contact with the Network of Neighbors. Community here is defined as any group of people with a common affiliations or experience (e.g., witnesses, first responders, neighbors, friends, classmates, etc). This means that this process may be in effect for multiple communities at the same time who were impacted by the same incident (in different ways) b. Components i. Virtual and in-person meetings with the impacted community’s natural leadership (Community Connectors) who can serve as trusted credible messengers, advocates, and gatekeepers for the impacted community. These community members are in the best position to re-establish a sense of emotional or psychological safety after the traumatic incident, which is the first step in assisting a community after a traumatic incident. During these meetings, Network of Neighbors Staff provide technical assistance, guidance, information and referrals to Community Connectors, who in turn provide the Network of Neighbors with the specifics in reference to 1) how their community has been impacted, 2) what the needs are, and 3) norms, boundaries, culture and local context. Skipping this step risks further harm to the impacted community, as well as increased distrust between the impacted community and supports and services available to it. ii. Identification of impacted subgroups within the community based on experience, relationship, as well as gender, age and development level (e.g. eye witnesses, neighbors, parents and caregivers, classmates, friends, colleagues, etc.) iii. Technical assistance, making use of existing resources, supports, and services – including the community’s own natural strengths and healing practices – service and support referrals (for individuals and families), and overall guidance around the implementation of a traumainformed community response. c. Goals: i. To establish a non-intrusive, compassionate presence to help the impacted community to marshal their own resources as well as existing supports and services in order to manage the short and long-term impact of the trauma in a way that taps into and strengthens the community’s natural resiliency and connections. ii. Assessment of community’s capacity to handle short-term (acute) issues (and identification of needed resources) iii. Assessment of community’s capacity to handle long-term psychosocial disruptions (and identification of needed resources) iv. Identification of leadership structure (to assist with responsive planning)

Stage 2 – Response Coordination

a. Description b. Components i. Response Planning with Community Connectors – Identification of a date/time for the response (or multiple), location, recruitment of impacted community members, messaging, etc. ii. Coordination with Responding Partners (system alignment)- information sharing and coordination of supports and services around the community’s stated needs and preferences. For Philadelphia public schools, the Philadelphia School District Office of Prevention and Intervention is always a Responding Partner, as well as Uplift Center for Grieving Children (when a student or staff member has died). Responding Partners vary depending on the impacted community’s existing relationships and connections as well as their stated needs. iii. Outreach to CTR’s (Community Trauma Responders) and internal DBHIDS supports/ programs. Depending on the incident, its impact on the community in question and their stated needs and preferences, the Network of Neighbors reaches out to their network of trained Community Trauma Responders to support the community response, as well as trained DBHIDS staff and DBHIDS programs that are appropriate for the specific response. The Network of Neighbors may consider specific needs and preference when reaching out to Community Trauma Responders and internal DBHIDS staff and programs: including language, experience, professional qualifications, affiliation with the impacted community, etc. The Network of Neighbors always completes a “Response Briefing” regardless of whether the community response is supported by Community Trauma Responders or internal DBHIDS staff. However, if they are invited to support their response, their participation in the Response Briefing is mandatory to ensure consistent communication and mitigate the risk of harm.

Response Coordination involves the planning of community and group-level interventions, recruitment of impacted community members, as well as the alignment of stated community needs with the available supports and services. This phase includes ongoing coordination with Community Connectors, as well as Responding Partners, which includes stakeholders and entities involved in the response process, either at the local or system level.

c. Goals

i. Alignment of community’s stated needs, boundaries, norms, preferences, and cultural considerations with available supports and services.

ii. Planning of a community response that includes the community’s voice and ensures that the response takes place as a date, time, and location that is safe, accessible, and convenient for community members.

Stage 3 - Community Response

a. Description

Community response involves community and group-level interventions that take place wherever the impacted community regularly meets or feels comfortable at a date and time that they have chosen. These interventions vary in their purpose and goals (according to the phase of the community’s healing process, or the time elapsed since the traumatic incident).

The goal section outlines the goals (and purpose) unique to the different kinds of interventions (PTSM, PIES and PGA). Overall, the goal of these interventions is to: i. Protect the space for the impacted community to come together for comfort, healing and connection. ii. Reduce and mitigate the impact of the trauma (stress) iii. Provide accurate information, either about the incident or about common reactions to overwhelming stress and practical strategies for coping. iv. Foster peer connection and healthy coping v. Identify community members who may benefit from additional support and services or higher levels of behavioral/mental healthcare. vi. Provide support within the context of the community so that the information and the resources are sustained with the community past the duration of the response. b. Components i. PTSM Orientation Sessions – 0-72 hours, or up to one week post traumatic incident open to the entire impacted community ii. PTSM Stabilization Group/s - Up to two weeks post traumatic incident – small group discussions for the groups with homogeneous exposure iii. PTSM Coping Group/s and PTSM Follow-Up Coping Groups – Two to three weeks – three month/one year post traumatic incident – small group discussions for groups with homogeneous exposure. Include suicide specific protocols. iv. PTSM Compassion Care Discussions – can occur anytime (preventative) or after a traumatic incident, depending on the nature of the impact and the experience of the community members. These discussions focus on the how the “work” you do impact you, which can include the work of being a part of a certain community of performing a certain job/role. v. PTSM Pre-Intervention Overviews – Structured information sessions/meet and greets, designed to build trust and safety with impacted community members before a PTSM small group discussion. vi. P.I.E.S. Discussion – P.I.E.S discussions are not part of the formal PTSM evidence and trauma informed curriculum but are used to build safety and trust with impacted community members before a group intervention. P.I.E.S discussions are also used within classroom setting and whenever the experience, relationship, and degree of impact of community members is unknown. vii. PFA Response – Psychological First Aid (PFA) is a one-to-one intervention (also appropriate for working with families), that is used by the Network of Neighbors during the Post Trauma Impact and Needs Assessment process, as well as during the P.I.E.S and PTSM intervention on an as-needed basis. However, PFA Responses involve dispatching Network of Neighbors (or PFA trained DBHIDS staff) to community events organized outside of the department to provide PFA support as needed.

c. Goals

i. PTSM Orientation Sessions – Dissemination of accurate information from stakeholders that can provide needed information (e.g. Philadelphia Police Department, Parks and Rec, Risk Management, Licenses and Inspection, etc.) to calm rumors and reduce orienting the community to additional supports, and identifying “Community Connectors” or potential subgroups of impacted community members.

ii. PTSM Stabilization – Emphasis on grounding and mindfulness techniques to reduce stress and arousal and safety plan for the short-term aftermath, including preparation for the funeral (if applicable) iii. PTSM Coping – Opportunity for similarly impacted community members to tell their story, discuss thoughts and reactions (normalize reactions), reduce stigma, received accurate information and support, discuss coping strategies and begin the healing process. iv. Compassion Care discussion – Address stress associated with the “work,” as well as challenges and rewards of the “work.” Compassion care discussions are preventative but sometimes utilized in the aftermath of an incident depending on the community’s unique situation and experience. v. P.I.E.S Discussion – Opportunity for community members to share thoughts ad reactions, support each other and assess/identify the impact as well as community members who cannot identify safety or support. vi. PFA Responses – PFA responses occur in community settings, designated events or in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic incident. The goal of PFA is to assess immediate needs of survivors and connect them to safety and support.

Stage 4 – Post Response

a. Description b. Goals i. Connection to long-term supports (e.g., internal DBHIDS programming, Uplift Center for Children and ongoing grief groups, or any supports or services that can fill gaps identified during the response process) ii. Ongoing technical assistance and Post-Trauma Impact and Needs Assessment iii. Trainings (in topic identified by the community to include Psychological First Aid and/or Post Traumatic Stress Management training) iv. Surveying of the Community Connectors for outcome and evaluation. c. Goals i. Provision and connection to long-term supports in a manner that respects the impacted community’s timeline, boundaries and stated needs and preferences. ii. Increased trust between the impacted community and existing support and services.

Post response is also an ongoing process, as multiple “responses” may take place over the course of several months or years. The process involves ongoing communication and checking in with the Community Connector/s who can monitor “the pulse” of the community and assess interest in additional interventions or supports.

External Stakeholder Learning Collaborative And Subcommittees

The External Stakeholders Learning Collaborative (ESLC) serves as an external engagement mechanism to discuss and receive feedback on the vast array of trauma activities funded and/or planned by the department, as well as an opportunity to discuss best practices, leverage opportunities to work with partners and increase knowledge across all stakeholders in addressing trauma. This group meets bi-monthly with the intent to exchange information and stay abreast of current programming and issues related to trauma, in the city.

The collaborative is comprised of 100-plus members: including community members, advocates, staff from community-based organizations and hospital systems, academicians, local subject matter experts and DBHIDS staff.

Subcommittees were developed to focus on specific priorities identified by the ESLC and subcommittee members. Subcommittees meet monthly and have thus far provided recommendations that DBHIDS has developed into multi-year work plans – what we refer to as “recommendations to action” to address the following areas:

1. Prolonged trauma

2. Trauma impacting children and families

3. Secondary trauma

4. Trauma related to violence

5. Defragging the system

Prolonged Trauma

The charge for this committee is to identify policies and practices to address prolonged trauma in Philadelphia. Below are the main recommendations. See appendices for the full Prolonged Strategy report.

1. Develop External Stakeholders Trauma workgroup. Include academicians, practitioners and community members.

2. Start with clear definitions of equity, power, privilege, diversity, and inclusion.

3. Identify various stakeholder groups for which trauma awareness training/trauma 101 and implicit bias training should be prioritized.

4. Develop trauma informed resources/trainings for pre-schools and daycares (ECE)

5. Identify specific, standardized metrics that are asset-based.

6. Standardize metrics that are collected related to trauma related from DBHIDS provider network.

7. Identify and provide specific resources to address STS and vicarious trauma among the peer provider workforce.

8. Develop trauma certification for CPS, CRS.

9. Revise polices that expel individuals for non-compliance with programmatic restrictions (not trauma informed) i.e., review policies with providers to ensure opportunities for further engagement versus expelling people from programs.

Children and Family Trauma

The charge for this committee is to identify areas to improve and/or expand DBHIDS services for children and families.

1. Young children 0-5. Need for immediate response to daycare and pre-k programs in events where young children are exposed to traumatic events.

2. Build capacity for trauma training of child and family serving organization and family members.

3. Expand TF-CBT into underserved areas, i.e. Southwest Phila – PACTS now has providers to serve these communities. PACTS will update maps.

4. Address workforce trauma training

5. Disseminate educational materials more broadly and widely, including community level.

6. Need for additional in class clinical support for ECE level providers.

7. Modify PACTS trainings to incorporate focus on racial trauma.

8. Children’s Mobile Crisis team- identify possible need for trauma specific training.

Secondary Traumatic Stress

This charge for this committee is to recommend best practices and provide resources for social service professionals.

1. Speaker’s series in the External Stakeholder Learning Collaborative.

2. Directory of supports for staff – Behavioral Health Community Supports Directory (Will be made publicly available on dbhids.org this year)

3. Partner with NAMI and NASW around messaging for the behavioral health workforce related to secondary trauma.

4. Social media messaging and infographic to access supports.

Defragging the System

The charge of this subcommittee is to recommend activities to reduce traumatic experiences and barriers people may face while trying to access services, through multiple systems.

1. Systems Mapping – DBHIDS plus other city health and human services agencies (Will be made publicly available at dbhids.org this year)

2. Identify systems to defrag (i.e., hospitals, schools, universities, city agencies, etc.).

Trauma Related to Violence

The charge for this committee is to understand how to serve and provide services and resources to individuals, families, and communities impacted by the trauma of violence.

1. Focus group with people who have perpetrated crimes to understand their perspectives and how they could have been helped.

2. Focus group with people who have been victims of crimes to understand their experiences of pre and post their trauma, including survivorship guilt.

3. Focus group with youth to understand their experiences with trauma in their neighborhoods and school environments, what supports they need and what they want adults to know about how to support them.

4. Public Service Announcements of DBHIDS resources.

5. Gun shootings mapping and responsive actions.

6. Annual TEC conference

7. Social media and infographic to access supports.

Proposed New And Innovative Programming

DBHIDS is also seeking funding for opportunities to create new programming to address youth experiencing trauma. Below are two new proposed programs and one program expansion that we see as urgent in implementing now to alleviate trauma for youth living in neighborhoods highly impacted by trauma.

1. Program - Trauma to Triumph

This program will disrupt the pervasive presence of trauma for low-income BIPOC people highly impacted by trauma by acknowledging their traumatic experiences, celebrating their strengths, and encouraging their hope and belief in themselves for a positive and productive future. The resources will be delivered with behavioral health supports.

The program will be designed to work in partnership with local nonprofit organizations and behavioral health providers that have demonstrated excellence in youth-focused, trauma-driven programming throughout the City of Philadelphia.

The program will serve 100 people between the ages of 10-24 over the course of 12 months. Selection of applicants will be prioritized for youth living areas that have high poverty and crime rates.

The program will consist of the following modules: a. Post Secondary Transition Supports b. Trauma Support Groups c. Turning Pain into Art d. Black Boy & Girl Joy

The anticipated outcomes include: a. Positive engagement of youth that promotes healing and well-being b. Increased hope for a positive and productive future as reported by youth c. Increased overall engagement in positive and productive activities as reported by youth

2. Trauma-responsive and Trauma-mitigating Programming with Community-based Organizations

This activity will address the pervasive trauma experienced by individuals and communities and must also include the work and efforts of existing community-based organizations engaged in gun violence prevention work. This recommendation comes from both the ESLC and Councilman Kenyatta Johnson’s panel. We see operationalizing this recommendation by: a. Soliciting 501(c)(3) organizations addressing trauma through: i. Innovative, non-conventional activities for at-risk youth in high crime areas. ii. Group supports for grieving families. iii. Piloting new ideas developed by people with lived experience to prevent and end gun violence.

3. Community Wellness Engagement Unit Youth Focused Support Team a. The team will engage children in settings such as: i. Schools (prioritizing community schools) ii. Out-of-school time programs iii. Recreation centers iv. Playgrounds and other public places b. Youth will be offered coping and life skills, referrals to services, and supports for the challenges children face including: i. Stress ii. Trauma iii. Social media-related issues including bullying, drill music, and damaging self-esteem messages. iv. Basic needs related to the social determinants of health and v. Behavioral health referrals included but are not limited to Tier 2 and T3 supports in and out of schools. c. The team will consist of a clinical-level supervisor, behavioral health workers, and community wellness specialists that will deliver in person programming. A family navigator will provide supports that will include the interest of the child and extend to the needs of their families as needed. And a program evaluator will ensure the goals and outcomes of the program are tracked, enabling the team to ensure that the programs’ strategies are effective and impactful. d. We anticipate this specialized team will bridge the gap in connecting behavioral health and related resources needed for children and families supporting children to have better academic and health outcomes. e. This work will help to reduce racial disparities by providing resources in communities that have experienced disinvestment due to structural and systemic racism. Addressing the social determinants of health and will support low income and BIPOC children who experience disproportionately higher levels of poverty access basic needs that can support their health and well-being.

This team will provide wellness supports in a variety of settings where children live, learn, and play. This work will complement available behavioral health supports and will focus on wellness and prevention. The CWEU Youth Focused Team will create a schedule and rotation each academic year ensuring there is capacity for all schools to be provided in person supports. A branding strategy will also be implemented to ensure all schools and families are aware of all of DBHIDS’ resources and availability to respond to school-wide and individual (parent, child, teacher) level concerns.

Achieving Equity

DBHIDS seeks to shift our systems to reduce behavioral health disparities through a variety of approaches and by intentionally addressing structural racism and advancing health equity and justice. We aim to make services more available and accessible to individuals and communities that have been historically underserved, close service gaps and improve service delivery.

In our charge to identify and change processes that create disparities, we:

1. Created the Social Determinants of Health Equity Unit in 2022 – this unit promotes health equity by connecting individuals with behavioral health needs to resources that address the social determinants of health.

2. Created the Forensic Equity Unit in 2023 – this unit will address the deep racial inequality within the justice system for people with serious mental illness by preventing incarceration for those at risk of justice involvement, reducing the length of stay for incarcerated individuals, reducing reincarceration for the justice-involved, increasing connections to treatment and support for those returning to the community from institutional settings, and targeting social determinants of health (SDOH). The unit’s focus on social determinants of health directly aligns with the Commonwealth’s Health Care Reform Recommendations by addressing food insecurity, health care, housing, transportation, childcare, employment, utilities, clothing, and financial strain within the justice-involved population with behavioral health challenges. These initiatives will ensure the success achieved in resolving the NSH waitlist is sustained while addressing the deep racial disparities within the justice-involved Philadelphia SMI population.

3. Transformed our crisis systems by: a. Expanded our Community Mobile Crisis teams to serve the entire city b. Implemented and promoted 988 and have seen a considerable increase in call volume with positive success stories and outcomes

4. Seek to engage BIPOC Providers (DEI and Racial Equity Change Team) a. Expanding our behavioral health provider network to include more BIPOC-owned and operated community-based behavioral health organizations that focus on a culturally and linguistically centered continuum of quality care to increase utilization of non-acuity behavioral health services and change the behavioral health service experience of Philadelphia’s BIPOC adults. b. Increased intentionality on BIPOC community collaboration and partnership. We are seeking to explore and develop new and innovative diverse community outreach and engagement strategies that advance knowledge and enhance awareness of our department and the vast array of resources, services, and treatment modalities we provide while recognizing the unique perspectives and needs of BIPOC communities in the way we serve their cultural differences. We are also committed to enhancing mechanisms to monitor the BIPOC Treatment experience to eliminate bias, racist, and discriminatory practices.

5. Included information on how to connect with BIPOC providers on Healthy Minds Philly

6. Use data to understand where there may be service desserts and/or where we may need to right size resources

7. Operate a Housing Unit – addresses the social determinant of health – housing, for street homeless individuals who are largely BIPOC.

8. Operate a DEI unit that houses Immigrant and Refugee Affairs and Language Access ServicesAssesses the needs of immigrant and refugee communities as well as service providers, to identify gaps and determine how DBHIDS can deliver culturally and linguistically appropriate services to the communities

9. Expanded Network of Neighbors in 2022 which allows the team to meet the needs of every community across the city through a regionalized approach.

10. Fully operationalized the Community Wellness Engagement Unit – regionalized throughout the city providing coverage to every council district to meet the needs of every community across the city.

11. Created the Racial Equity Opioid Overdose Committee in 2022 to address the rise in overdose deaths in BIPOC communities and equity in services and delivery.

In our charge to review and evolve hiring, contracting and community engagement processes and practices to reduce disparities, we are committed to what we call “conscious contracting” that aims to remove barriers and promote equity.

Additionally, we work internally to ensure that staff across all divisions and levels of leadership are representative of the communities of we serve.

2023 Minority, Women, Disabled/Disadvantaged Business Enterprises Statistics for our provider network and DBHIDS.

1. Over 90 percent of DBHIDS funds support non-profit agencies

2. 79 percent of DBHIDS staff are minority

3. DBHIDS Executive Leadership – 75 percent minority, 50 percent women

4. D DBHIDS Contracted Agencies – a. Workforce – 52 percent minority, 65 percent women b. Executive – 33 percent minority, 59 percent women c. Board of Directors – 40 percent minority, 44 percent women

Moving forward in 2023, we plan to:

1. Continue DEI efforts to increase diversity in the provider network.

2. Host focus groups with BIPOC providers to understand challenges and barrier with becoming part of the network with the goal of increasing the number of providers.

3. Conscious contracting - work to increase diversity in the provider network by valuing cultural competence, community presence and other factors that are consistently valued.

4. Develop monitoring tools that track data points that can ensure services are equitable delivers in every community.

5. Continue data-driven responses to racial and geographic disparities.

6. Continue our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts to address racial equity in the overdose epidemic.

7. Publish the Behavioral Health Supports Directory which lists providers by categories including: LGBTQ, BIPOC, Seniors, Immigrants and Refugees, Intellectual Disabilities, Secondary Traumatic Stress, Deaf/ Sign Language Needs, Children’s Supports, Sight Impaired, and Domestic Violence.

8. Host TEC tours in neighborhoods across the city to understand the unique needs of the people and the identities of those communities in addressing trauma and delivering services.

9. Seek sustainable funding sources to continue to address the social determinants of health for the people we serve.

Engaging Community

We work across the city every day through numerous teams and in a variety of formats. We seek solutions from and sustain solutions in communities. We also actively seek to embed sustainable funding and operational activities within our providers and community-based organizations where possible.

Below are some of our programs that actively engage and work in partnership with communities. A listing of all the programs across the Department organized by TEC category can be found in the P.A.C.E. /TEC Crosswalk. (Some programs that engage communities are also noted and already defined in the trauma section of this report)

1. Engaging Males of Color

2. Community Affairs – provides behavioral health resources and information at community events across the city.

3. Community Wellness Engagement Unit

4. Faith and Spiritual Affairs (FSA) - Engages the faith-based community, organizes the FSA Advisory Board, hosts an annual conference, and is dedicated to: a. Enhancing understanding of behavioral health conditions b. Reducing the stigma associated with behavioral health challenges. c. Promoting inclusion and connectedness in one’s community, d. Aiding in the integration of spirituality into behavioral health care and treatment

5. Porchlight program with Philadelphia Mural Arts

6. Immigrant Refugee Wellness Academy- In 2022, DBHIDS launched the Immigrant/Refugee Wellness Academy (IRWA) pilot program. IRWA is a free training program designed to empower and prepare Philadelphia’s multilingual/multicultural immigrants and refugees with knowledge, resources, and tools necessary to engage in activities that address behavioral health and intellectual disability challenges, trauma, and inequity experienced within the immigrant and refugee community. The benefits of this certificate program include behavioral health and intellectual disability knowledge and understanding,

7. Peer Culture and Community Inclusion - PCCI is a community partnership promoting pathways to wellness. Our goal is healthy individuals, families, and communities, free of stigma, with equal access to health resources sharing their lived experiences for continued holistic wellness. In order to realize this mission, the PCCI Unit actively engages, supports, and models the promotion of hope, wellness and empowerment throughout the Behavioral Health system of Philadelphia and beyond

8. Mobile Outreach and Recovery Services

9. Homeless Outreach and Huddles - Street outreach engages homeless individuals living on the streets of Philadelphia. Staff offers emergency housing and treatment options as well as water and assistance meeting their immediate survival needs. More important for persons experiencing chronic street homelessness, street outreach represents building reliable relationship that assist individuals in addressing barriers to coming inside. Outreach assists persons in identifying their needs, wants and desires as they recover their lives. Outreach acts as a bridge to a life beyond street homelessness. Outreach Special Initiatives Unit along with AR2 and the Managing Director’s Office

10. Philadelphia Systems of Care/Councils - (PSOC) - Community-driven councils that are representative of local neighborhood families, youth, and partners, who are committed to community empowerment and to addressing the social determinants connected to youth behavioral health, resiliency, and wellness

11. Youth M.O.V.E. Philadelphia - is a local chapter of Youth M.O.V.E. National (Motivating Others through Voices of Experience). YMP is devoted to improving services and systems that support positive growth and development by uniting the voices of individuals who have lived experience in various systems including mental health, juvenile justice, education, and child welfare.

12. Suicide Prevention Task Force - The Philadelphia Suicide Prevention Task Force (P-SPTF)’s mission is to work toward zero suicides in Philadelphia. This mission will be achieved through a collaboration of all stakeholders and by engaging in a coordinated and integrated approach across the city.

13. TEC Talks and Community Conversations hosted by Dr. Jill Bowen - engages community members, staff and our provider network in addressing TEC

14. Family Committee - Family Member Committee is comprised of family members of children with a variety of behavioral health needs. These meetings provide an opportunity for family members to network with each other, receive support and to also provide input into policies and programs of DBHIDS affecting children and families. It is a safe forum where family voice is heard and can move our system in directions that better serve children and families.

15. Community Autism Peer Support (CAPS) - program pairs an individual with autism who has completed a peer support training program, with other individuals with autism to achieve personal wellness and community participation goals

Moving Forward in 2023, we plan to:

1. TEC Talks and Community Conversation - conversion and expansion to podcasts

2. Distribution of materials in new spaces this year- i.e. 52 public schools, more playstreets.

3. Create an external facing web page for the community to learn about and have the opportunity to join our community groups.

4. Ensure ongoing representation, post TEC tours, at community led events, as requested by communities.

Tec Workplan

Short-term 1 to 12 months (green); Mid-term 13 to 24 months (blue); Long-term 24+ month (dark blue) Implementation Schedule

Trauma

Prolonged Trauma

1. Develop External Stakeholders Trauma workgroup. Includes academicians, practitioners, and community members

2. Start with clear definitions of equity, power, privilege, diversity and inclusion

3. Identify various stakeholders and groups for which trauma awareness and training 101 and implicit bias training should be prioritized.

4. Develop trauma informed resources/trainings for pre-schools and daycares (ECE)

5. Identify specific, standardized metrics that are asset based.

6. Standardize metrics that are collected related to trauma from the DBHIDS provider network

7. Identify and provide specific resources to address STS and vicarious trauma among the peer provider workforce.

8. Develop trauma certification for CPS, CRS.

Children and Family Trauma

1. Young children 0-5. Need for immediate response to daycare and pre-k programs in events where young children are exposed to traumatic events.

2. Build capacity for trauma training of child and family serving organizations and family members.

3. Expand TF-CBT into underserved areas, i.e. southwest Phila.

4. Address workforce trauma training.

5. Disseminate educational materials more broadly and widely, including community level.

6. Need for additional in class clinical supports for ECE level providers

7. Modify PACTS trainings to incorporate a focus on trauma.

Committees or other Recommendations or Activities Term

8. Children’s Mobile Crisis team - identify possible need for trauma specific training

Trauma Related to Violence

1. Focus group with people who have perpetrated crimes to understand their perspectives and how they could have been helped

2. Focus group with survivors of crimes to understand their perspectives and how they could have been helped

3. Focus group with youth to understand their experiences with trauma in their neighborhoods and school environments, what supports they need and what they want adults to know about how to support them.

4. Public Service Announcement of DBHIDS resources

5. Gun shootings mapping and responsive actions

6. Annual TEC conference

7. Social media and infographic development on supports

Defragging the System

1. Systems Mapping of DBHIDS and other city health and human services agencies. Make DBHIDS mapping tool publicly available on DBHIDS.org

2. Identify systems to defrag (i.e. hospitals, schools, universities, city agencies, etc.)

Secondary Traumatic Stress

1. Speakers Series in the External Stakeholder Learning Collaborative

2. Directory of supports for staff - Behavioral Community Supports Directory. Make publicly available on dbhids.org

3. Partner with NAMI and NASW around messaging for the behavioral health workforce related to secondary trauma.

Committees or other Recommendations or Activities Term

Gaps and Recommendations

New and Innovative Programming

Equity

1. Develop a plan to prioritize and implement feasible recommendations

1. Seeking program funding and support. If awarded will implement within 6-12 months, post award.

1. Continue DEI efforts to increase diversity in provider network.

2. Host focus groups with BIPOC providers to understand the challenges and barriers with entering the network – with the goal of increasing the number of providers

3. Conscious Contracting- work to increase diversity in the provider network by valuing cultural competence, community presence and other factors that are consistently valued.

4. Develop monitoring tools that track data points that can ensure services are equitable delivers in every community.

5. Continue data driven responses to racial and geographic disparities

6. Continue Diversity, Equity and inclusion efforts to address racial equity in the overdose epidemic.

7. Publish the Behavioral Health Supports Directory which lists providers by categories including: LGBTQ, BIPOC, Seniors, Immigrants and Refugees, Intellectual Disabilities, Secondary Traumatic Stress, Deaf/Sign Language needs, Children’s Supports, Sight Impaired and Domestic Violence

8. Host TEC tours in neighborhood across the city to understand the unique needs of the people and the identities of those communities, in addressing trauma and delivering services.