MIRAGE 2024

“I don’t like it.” Cameron clicked his blue ballpoint pen before he slid my short story back to me.

“ Why?” I asked too forcefully. This wasn’t an argument. There was no need for my guns to be drawn. “You just don’t get it. It’s a profound commentary on–”

“ That’s the issue. It’s trying too hard to mean something.” He gave two more judgemental clicks of that pen and met my blank stare.

For once, I was without so much as a single word. In a room so suffocating, I wondered how Cameron found it so easy to breathe.

“Everything means something,” I finally managed to say.

“Doesn’t have to.” Cameron shrugged and clicked that pen twice. “Some things mean nothing at all.”

–– “A Profound Commentary,” Jackie Adams

Mirage 2024 Dana Hall School

Dedicated to Cara Hanig

To Ms. Hanig,

Throughout high school, we want to explore, to fly, but like kites, we can only soar against the wind when we are anchored. You were that anchor, keeping us tethered when we were drifting among uncertainties. As a college counselor, you were dependable and wise, patiently listening to us, thoroughly answering our every question, and reassuring us that ultimately, everything will be okay. As a coworker, you never ceased to amaze with your talents, your sense of humor, and your unwavering dedication to putting students first. Most importantly, you became a friend to all of us.

As you embark on new adventures and reach greater heights, we hope you remember that our love for you is firmly anchored in our hearts. May your journey ahead be filled with joy and success.

AN AMERICAN WELCOME

Nia CaoAt age six, I did my first act of assimilation: stabbing my name in the back.

Four letters turned to three when my Kindergarten teacher stumbled over its body and gave life to a substitute: unaccented, unfamiliar, and English. She taught me a lesson that day: the Vietnamese name that flew with me across lands and seas stood no chance in America.

When I stuck by its side, knuckles rapped against wood, four letters were singled out, the whole world seemed to ask: “How do you pronounce this?”

My betrayal was easy—natural. I wanted to be called the right thing the first time. I wanted to fit in amongst the Jack’s and Jill’s.

Like Ariel who gave up her voice for feet, I traded my beautiful name for something so desirable: acceptance.

The shame silenced me, and I never fought back. Shadowed by parentheses, I refuse anyone the chance to grasp its story.

The knife only I can see remains lodged in the O. I twist it deeper by calling myself another. Forgive me.

At age six, I did my first act of assimilation: stabbing my name in the back.

STREET BEHEMOTH

Sophia (Micheline) ReidJohanna once told me, with her hastily dyed hair and her accented English; take your chances when you cross the street…no one will stop for you. I don’t remember them, all the times our feet ricocheted off the ground, peeling across the muddy road with Johanna, shearing the pavement on Vienna Avenue.

Oh, Johanna was taking her chances when her life halted in a blink, crystallized in the blinding blinkers of the car, under the pale street lights. Nothing in the road stopped for Johanna, and time did not stop for me.

Af ter she’d been lost on Vienna Avenue, what could I do? What could I live for? Shall I take a risk ever again? Do I swim in the sea with a chilling behemoth, because I want to feel the cool water across my face? Do I wear the dress that has bestowed every wearer with bad fortunes, because I want to feel illustrious? Johanna knew you could never hide from living, and should I never touch the streets, the sea or the age-old dresses ever again?

That question was the greatest gift, one asked by my dear Johanna in the middle of a daydream, one I could not answer. I take my chances every time I speak. I take my chances when I see her face in someone standing before me. I take my chances every time I cross the street.

GIGI’S CLOSET

Sloane O’Reilly

All in a neat line, row by row, white shelves hold the pairs until there is someplace they need to go.

Canvas, leather, new and old, from cherry red, to bright sunny gold. Ready for every occasion, they need no persuasion.

If these soles could talk, stories could be told of people who were met and places they’ve been to, new and old.

Time passes on while they wait for their turn. To experience the world, until it’s time to adjourn.

THINGS WE CARRY

Cassandra Sophocles

We carry each other as we go from one house to another. We carry tears as we leave, knowing we’ll be in the same spot next week. We carry the blood from our parents, two people who hardly speak.

We carry our grief, stacked on top of us and never fully healed. We carry laughter, the only thing that seems to heal us in times like this. We carry two names: one reserved for our mom, the other for our dad.

We carry bags, filled with our belongings as we move from place to place. We carry years of memories my parents choose to forget. We carry our love with us as we go, two hearts instead of one.

We carry forced smiles and reassurances, never wanting anyone to see behind them. We carry hatred for our parents, though we know it isn’t fair. We carry two lives, split in half when my parents did.

We’re children of two houses, but never a home. And we carry on our family as we move back and forth... back and forth... back and forth, in the never ending cycle.

RAMEN

Samantha MayerIn the kitchen’s embrace, where memories stir, Ramen tales of resilience and love confer. My mother’s past, woven in broth and strand, A duty she bore with a diligent hand.

Before the shadows claimed the day, Homework and shiny metal pots in a ballet. A young heart burdened, yet hands so deft. Creating dinners, homework’s silent theft.

Chashu swirls like poetry, tender and divine, Egg’s golden yolk, in a soft, savory line. Green onions waltz, seaweed adds its grace, In this ramen symphony, a culinary embrace.

Yet, now in the present, a different scene, A mother’s love in every cuisine. The broth tells stories of battles won, Ramen strands under a caring sun.

She stirs not just noodles but tales of the past, A duty transformed, a love steadfast. For you and your sister, a shift in the tide, In each bowl, a mother’s love resides.

Ramen now a bridge, not of obligation, But a legacy passed, a tender foundation. In the steam’s embrace, stories replay, Of a mother’s journey in each noodle’s sway.

BECAUSE IT’S PRECIOUS

Jenni DingPrecious, adjective: 1. Rare and worth a lot of money; 2. Valuable or important and not to be wasted; 3. Loved or valued very much; 4. (Informal) very attractive and easy to feel love for; 5. [Only before noun] (informal) used to show your anger at another person’s overvaluation of something; 6. (disapproving) (especially of people and their behavior) very formal, exaggerated, and not natural in what you say and do.1

7. Van Gogh’s authentic paintings; 8. The vintage piano that Mozart played during his childhood; 9. Your lovely pet; 10. An unforgettable friendship.

11. You wore a lemon yellow dress, pointing at me, asking, “Who are you?” when you saw me hanging out with my friend, who lived next to you.

12. Surprisingly, we met each other again. You became my classmate in the last year of Kindergarten. You quickly came to be one of my best friends because we lived in the same neighborhood and had already seen each other before you were in my class. We stayed together and even wanted to sleep over every day. We had endless stories to share and missed each other at the moment we were separated. We never fought over anything and only gained lovely moments every time.

13. Remember you went to Changshu with me in midsummer? Mom allowed me to go with only one friend, and I chose you. She took us to a popular local noodle restaurant that had been on TV because of the delicious food. We sat outside despite the hot weather, enjoying crickets and cicadas chirping, the shade of the trees, and the wind different from the coolness of the air conditioning indoors. It turned out that we didn’t even finish one bowl of noodles. Instead, we spent our time running around, catching crickets, and looking for snacks like chips and ice cream in grocery stores beside the restaurant while Mom was enjoying her food. Both of us sweated so much our t-shirts were soaked, so we clamored for popsicles until mom couldn’t stand it anymore and bought one for each of us. The green apple-flavored popsicle had jelly outside. I have loved this type of popsicle since then.

14. The hiking journey started as soon as we finished the popsicles. The steep path made even mom pant, let alone me as a 6-year-old child. You sat beside me on the bench to encourage me when I got too tired to go further and shouted about giving up and going back. You held my hand and led me to go up step by step, saying that the closest twins couldn’t be separated from one another. At the top of the mountain, you hugged me and yelled, “We will be besties forever!” I didn’t say anything but nodded and made the same wish silently. It was the last trip we went on with each other.

15. I couldn’t believe your words at the moment you told me you would leave our city for Shanghai for primary school. It felt sudden; you never told me you planned to live there before, but that was your choice to start a brand new life in a better city. I hoped you could have a good and happy life there.

16. You still called me in first grade regularly; we shared what we learned with each other, from new English words like “apple,” “pear,” and “animal” to Chinese pinyin “sh,” “zh,” and “ü” on the phone. Every summer, I visited you for a whole day; that was a long time but not enough for two kids who couldn’t see each other for the entire year. 17. Gradually, as both of us had new friends and lots of work to do at school, we didn’t talk so often anymore. I still considered you as my best friend; I think you did, too.

18. When I looked forward to visiting you again in fifth grade, you told me you went to Ningbo, a further city, too far for me to visit you during holidays. We could only talk to each other on WeChat. You became a little actress acting as a minor character in an office drama; when the show came on TV, you asked me to watch it. I still remember your rosy red dress in the show; you looked adorable in it.

19. Since then, we have rarely talked to each other, because of the distance outside and inside. Posts on social media were the only way for us to see each others’ lives. I didn’t know how to start a conversation out of nowhere, even though I wanted to so much. 20. I knew you went to another country with your mom last year. We live in two different countries far from each other now, which is the latest news I know.

21. Last week, you found a picture of us at my birthday party; it was taken a long time ago, probably over ten years, and you shared it with me, saying “Time flies.” It seems that nothing has changed, but something has changed indeed. 22. Are we still best friends? I hope so; I don’t know. We met and got to know each other luckily by coincidence, and a year later we started to experience countless farewells, like two tracks separating further apart after momentarily joining parallels. Maybe this is so-called destiny.

23. It seems that all the memories about you are from a long time ago. People ask me why I can still remember every detail about you. I will always say, “Because it’s precious.”

FLAT EARTH

Ana LeblThe Earth is flat, it must be flat. Inconceivable, the idea that you are beneath me, so far away. Only a flat earth makes sense. How would I walk to you without following a straight path, a single branch? I can live knowing it’s flat. Knowing that you are nearby, knowing that I don’t need to roam the world in search of you. Funny to think that they deny such a land. A land I can trust from the beginning, since love was conceived by men. I promise you, my land is not round.

If I couldn’t glimpse the supposed end of the world, I would have to live in our uncertainty.

REMNANTS OF

Penny WeiDecember 1970. Peking, China

Four years into the Cultural Revolution

Yulan-Gu still recalled the glow of moonlight on the night of Ba-ba’s suicide. The celestial realm sang songs of solace, casting a layer of amber hue upon his cold, stiff body. The light illuminated all — the congesting vessels of blood around his bulging pupils, strands of gray messy hair, the firm lasting grip on his hand, and the piece of Qing-shi yan he held in it.

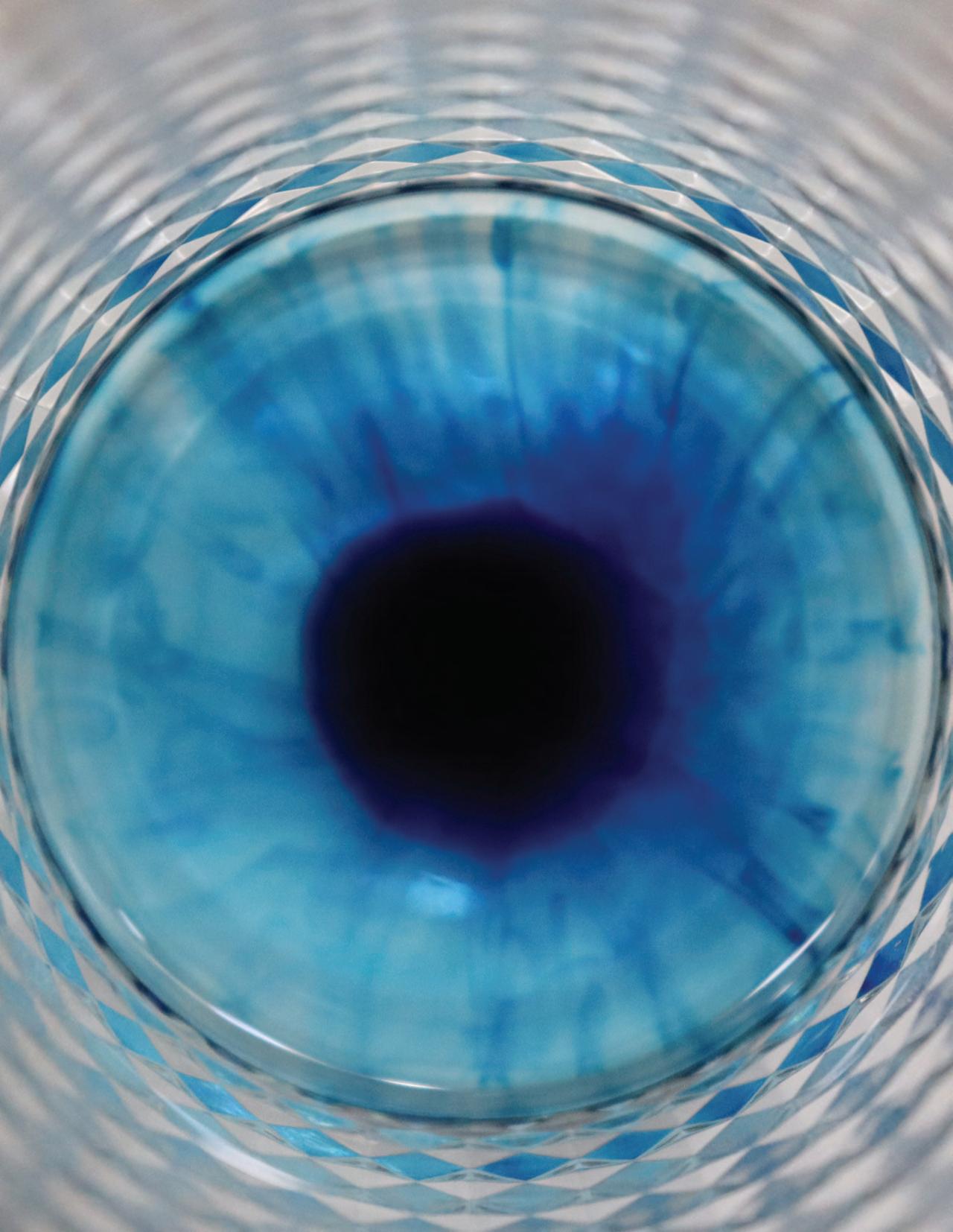

The Qing-shi yan was now dangling on her neck. Looking down, the gem glimmered a radiant blue hue like the waves of an untouched ocean. She wrapped her hand around it, the warmth of the palm lingering even after she took her hand away.

Ba-ba’s death seemed decades ago.

If it were not for the gem, she might have forgotten all together.

Yulan stood in the factory, observing Ma-ma weave, her creased hands– now weathered from laborious toils– were threading yarns of warp through the heddle, intertwining dull threads until they formed intricate tapestries. Ma-ma always beamed at the delicacy of beautiful textiles. She was not smiling now.

Never-ending, non-stop. Ma-ma was young no more. The lightless chambers, home to ignoble dealings of blood and banknotes have drained her soul. She was crammed with dozens of women, row after row, body after body, in damp, humid air. Sometimes, Yulan searched for something in her mother’s eyes, whether it was wrath, loathing or misery— she found only vacancy. Ma-ma was no more than a corpse. So was Yulan herself.

Ma-ma told Yulan to go home and wait. So she did. She had nowhere to go, she had nowhere to stay. Outside the factory stood her old school. A pristine layer of snow lay on its facade, weathered and worn. The building stood dormant, serene, useless. Years of raging protests have long sealed the entrances to school gates. She was left wild, with two possible trajectories: to join as a Hong-wei bing or to stay wild.

She took the road less taken.

Her thin tunic didn’t shield her from the January wind, permitting gusts of frigidity to thrash at her face until what was pale morphed into sour-red. She did not care. In the corners of this dilapidated city, Hong-wei bing bound the hands of intellects with coarse ropes, unmoved by the pleas of wives and cries of children. Heads of wisdom yield to conformity. She looked to the side. Dense plumes of acrid gray rose from crackling flames, the very same flames that devoured the studies and books of Ba-ba.

Books. It has been long since she ever touched one. It was as if just seconds ago she tiptoed beside Ba-ba, curious about the manuscripts piled on his desk. Ba-ba was a history professor in Peking University, one of the few in the country. From a young age she knew that Ba-ba roamed in the world of the past, diving into scrolls and codices drafted with characters she barely understood.

“Ba-ba what are you studying about now?” She would ask at the age of seven.

“ The Xia-dynasty, all of our ancestors who made us who we are now.” Ba-ba gave her head a pat. “I sense your boiling curiosity Lan-lan. Are you interested?”

She nodded and Ba-ba pulled her onto his firm lap, a place she sat for years and learnt about the history of her nation and neighboring nations and exotic nations until she grew too heavy to be held. She never listened carefully, all she knew was that Ba-ba smelt of pure sunshine.

Though none of that mattered now.

The attic, one of the few remaining properties she and Ma-ma owned, had seen better days. Now the walls were dingy, the curtains tattered. Furniture was scarce: in the corner stood a little wooden desk, and beside it rested a closet too worn to be opened. She sat by the desk now vacant from disuse. The attic was no good for a home. Yet, it was the attic where Ba-ba used to commit himself in hours of study until the brush of his Maobi splintered.

It was the attic that preserved the remnants of Ba-ba best.

At the age of eleven, she climbed all the way up the stairs to the attic, and Ba-ba shared with her the history of his favorite gemstone, the Qing-shi yan, how it came from Northeastern Afghanistan and symbolized everlasting courage and truth. She asked.

“Ba-ba, what is the purpose of learning history? Isn’t the past always going to stay the past?”

Ba-ba’s articulating mouth came to a sudden halt.

“ You’ll see Lan-lan. You’ll see.”

But she never saw.

Her fingers brushed away the ashes accumulated on the rough surface of the wooden desk, just as Ba-ba used to.

In 1963, after her eleventh birthday, her Ba-ba Jiegang-Gu published the Gu-shi bian. While his writing, a challenge of past historians, made little sense to her, she understood the aftermath: in the years that followed, Ba-ba was defamed and reprimanded, his opponents ignorant, his audience mundane. One would yell on the streets to assassinate Ba-ba, while another would write him letters of deprecation, full of vile words.

“All these will not kill me Lan-lan, your Ba-ba’s too strong of a kind.”

Yulan frowned. What was the point of all this, if Ba-ba would only get hurt in return?

Now, her fingers traced the patterns on the curtains. Rays of winter sun pierced the thin layer of fabric, its warmth resembling the ones from many years ago.

On the bright, warm days of May 1966, when rays of sunlight pierced the unfurling leaves of spring, came surges of revolutionary uprisings: the eyes and voices of young men, determined and ablaze. Yulan overheard her maids murmuring of a movement to clear the dictatorship of the “bourgeoisie” and defeat “monsters and demons.” Yulan nodded, admiring these acts of justice. Or at least, what she thought to be justice.

But Ba-ba was one of their first victims.

One day she came home from school, beaming about the perfect score she got on her dictation quiz, only to see Ma-ma’s weeping figure curled on the ground.

She ran up to her.

“Ma-ma what happened?” She looked around. “Where is Ba-ba?”

Ma-ma kept on weeping. A haunting, raw melody of despair. The roaring crowds outside the window.

She did not go see Ba-ba’s struggle session. But the maids whom they no longer could afford gossiped about Bab-ba. They said he was beaten, tortured in the face of hundreds. They said he wore a dunce cap taller than all the scrolls and codices he had ever read packed together. They said that at the end, Ba-ba lay on the ground in dripping black blood.

Ba-ba committed suicide the very next day, in the attic where he used to study, with a brushless Maobi he shredded into the tip of a knife. After his suicide came more: schools were closed, shrines were torn, books were burnt, and more of the bourgeoisie class were persecuted. All of Ba-ba’s work vanished in quick, fiery flames.

All of their assets were divided among the people. They were wealthy no more. The only thing she kept was Ba-ba’s Qing-shi yan, which she later threaded into a necklace she wore on her neck. Whatever Ba-ba clenched in his firm grip, she did too.

Yulan looked down at the Qing-shi yan hanging on her neck.

R adiant blue hue like the waves of an untouched ocean.

In a moment of resolve, she decided to take it off, the first time in years.

She held it with both hands. The gemstone was too heavy for a normal stone. Yulan studied it, her fingers tracing through its edges and rounds.

Click.

The gemstone cracked into pieces on her palms. She shook in a moment of misery. What had she done? But then, beneath the thin layers of stone, lay a metallic key and a note.

Through the blurry writing, she read: Closet.

Closet? She moved towards the only closet in the attic, the closet too stubborn to be opened however they tried. She turned the key and opened the door. Concealed inside were hundreds of scrolls and codices.

In the midst of them, she saw in bold letters: Gu-shi bian. She took the scroll out and flipped through its damp pages, soaked with the humidity of time and Ba-ba’s dedication.

Now, she finally comprehended Ba-ba’s work. At the age of 18, she knew. She knew that Ba-ba doubted the authenticity of ancient chinese historiography, that he questioned philosophies of antiquity schools, that he criticized intellectuals who aligned with aristocracy instead of pursuing truth. He walked against the crowds of conformity, with unyielding steps but wet hands, the latter in which only Yulan knew, as what he held in his hands were hers.

Ba-ba was defamed and reprimanded by opponents. Amongst all this Ba-ba did not care. He held Yulan’s hand in his, his steady eyes in hers.

The attic door creaked open, and then followed familiar scents of yarn and textile.

“ Ten other women joined the factory today–”

Ma-ma’s hoarse voice came to a sudden halt.

In the solitude of the attic, dust particles danced in slanting sunlight. The two stood in front of the opened closet. They stared at yellow scrolls that told what was unspoken, what was silenced.

In the solitude of the attic echoed the pounding heartbeats of three.

Yulan turned around, only to see Ma-ma blink.

Yet Yulan was sure she saw a flicker of something more.

May 1971. Peking, China

W inter slipped away through the crevices of Yulan’s palms and along with it, gusts of roaring wind yielding to the warmness of spring. Things merely changed: Hong-wei bing still reigned the streets, altering fates of the innocent, as more books vanished in the thick, choking flames. Ma-ma still worked in the factory, threading yarns of warp through the heddle, with more women joining them every hour.

All was the same, except Yulan no longer followed Ma-ma to the factory anymore. She sat herself in front of a rugged, wooden desk, her fingers wandering over the pages of ancient scrolls and codices, comprehending what she never comprehended before. She learnt about the ancestors of the Xia-dynasty, she learnt how the Qingshi yan originated from the Northeastern Afghanistan, she learnt about the history of her nation and neighboring nations and exotic nations. She excavated Ba-ba’s works, studying, foraging, navigating, until the brush of her Maobi splintered from use.

Yulan’s fingers lingered over the Qing-shi yan, its weight now absent from her neck. Her thoughts wandered to the possibility of a different future.

Maybe. She thought. Maybe someday she would be able to bring Ma-ma out of the lightless chambers, to stop all this turmoil. Maybe the stories in the dusty scrolls, the wisdom of history, the courage of Ba-ba, could all blossom in the sunlight and inspire hope in these trying times. A flicker of hope to mend what was broken.

Af ter all, with Ba-ba’s hands in hers, what was there to be scared of?

I prayed to God and begged for death, so he sold me off to bullets and bets

I am the exotic creature you “rescued” from a rural village amidst a crumbling country (the one you decimated),

and when your eyes descended upon me, ransacking my body, I became aware of my fate: an extra in this cinema of horror.

You made my land a battleground, dropping bombs that fall loud as the cries of wide-eyed children for their mothers

and quick as the times it takes for the stench of decaying bodies to waft through smoke-filled air: when will it be enough?

I was not human but a liquid smooth beauty, smothered in silky napalm and naivety, possessed with a duty to serve you and all your needs.

I know you. I know you.

You like us Oriental girls with Agent Orange in our blood. You like us Oriental girls with our thick accents and minds rocked dumb after you decided

to pop ‘em all up. You like us Oriental girls that are ripe and ready for you to ravish, made from your war and your guns and your ambitions.

I will become a statistic like my sisters before me, and you will go home to your wife and kids once you’ve done your duty.

My family is dead, my people are dwindling. God has abandoned me.

You never even asked for my name, and that’s why you’ll call me baby, temptress, fantasy since I’m nothing more

than what you imagine me to be.

to the progeny we cannot sever Yufei (Caitlin) Kuang

when you came into this world, did you pass by my heart? did you wander through my body, play hide-and-seek between my bones? did you swim through my veins, and wade through my waters? did you claw through my flesh, buried alive in a living grave? and was my blood the only thing warm and vivid enough to feign love? was my blood the only thing that connected your heart to my own?

you erupted from me like an aneurysm, all covered in blood, so shriveled and bloodied, with such thin, fragile bones. i gazed upon your body, which i birthed from my own, as they placed you in your cradle, velvet-cushioned like a grave. you soon learned to cry to replace the lost warmth of waters, and my milk soon ran dry, so you sucked out instead my love.

your birth was announced like an eulogy: somber and grave. the words washed over me in a tide, a flood of killing waters. i was sick for weeks after, in my heart, in my blood, in my bones, and yet you thrived robustly, on that red knot of a heart that used to be a knot in my stomach, but lives now on its own, and yet i’m still chained to you by the obligation of love.

your neck was wrapped in a cord; ’twas i who felt a noose around my bones. a noose called motherhood, a supposed synonym of love eroding my being, long a tumor in my heart, eating away my tombstone. the only name left on my grave: “loving mother of you,” as if i were something that you own (when i want to be buried by sea, swept away by its wild, free waters).

do you remember that once, you and i were one, my love? and perhaps we still are, for your blood first ran from my own. your flesh was peeled from my belly; your skeleton stemmed from my bones. you once drank from me life, drank my milk like water. you were a backwards thorn pulled out, now a scar in my heart, permanent as folds on my torso, marks of you in me, until i fade in my grave. when you came into this world, you shattered my lower bones. you opened your eyes, eyes that would see me to my grave. you bit at my flesh, so hard my eyes began to water, and you clasped onto my heart, clutched it, clenched it, called it love. i held you in my arms, as delicately as i would my heart, and finally there was a tragedy that i could call my own.

do you love me? you would ask me. my child, i love you to your bones, since you were a sinful cell in my waters, until my heart withers in my grave. and i hate you, my cage, for your life is a reminder, that once, my body had not been mine to own.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EDUCATION

Hilary ReuterEvery early August, Osma Harrell, accompanied by his parents and four siblings, would make the trek from their hometown in urban Georgia to rural Georgia to see his grandparents. Every year he would wait with apprehension, until the moment when the paved roads turned into winding, dusty paths, overrun with blades of sunstreaked grass that were just a few too many inches overgrown. When the sharp smell of gasoline-powered automobiles became the scent of freshly picked tobacco and peaches. Until packs of mosquitos swarmed the humid evening air, covering the star-filled sky with a layer of haze. Sitting out on the porch, awed by his grandparents’ stories that were colored by deep southern accents and cigar smoke, Osma soaked up these memories. He cherished these moments with his grandparents when he was little.

However, by the age of seven, he began to recognize the harsh realities of this lifestyle. The ongoing labor it required. The constant buzz of a tractor. Even the rolled-out green fields that once seemed bright and cheery, now simply served as a reminder to Osma of just how far from civilization he truly was. After countless summers of laboring in the tobacco fields with his siblings, while his grandma scrounged for enough ingredients to feed the hungry faces each night, Osma realized that his own life would echo many of the experiences he endured at his grandparents’ home if he didn’t make a change.

On special occasions, his grandparents would pick one hard-working grandchild to spoil and take out into town for the day. “Town” consisted of a market and a doctor, but Osma always loved these excursions. He would immerse himself in the black and white magazines that featured new innovations and sharp men in suits. Osma would often envision himself being one of those successful businessmen, imagining the people he would meet from all around the world. These childhood fantasies are what sparked his initial interest in the possibility of school. However, because his father was a shoe shiner and his mother was illiterate, his family was too poor to afford to send all of their children to school. Osma knew better than to expect this dream to ever become a reality.

On those rare occasions when rain coated the ground enough to produce mud, Osma would rip a stick off a mossy tree on the outer perimeter of the property and practice tracing words he had seen in his father’s most prized possession, the family bible, in the wet earth. He loved the curve of each letter: the small scoop of a “J,” the symmetry of a capital “H.” Osma found each letter to be pleasingly unique.

Aside from these muddy days, he and his siblings spent their days doing household chores and reading his father’s bible. His family was highly devout, and Osma’s mother spent a large portion of her day mumbling prayers in hopes God would someday bless their family with prosperity.

One day, Ms. Harrell’s prayers were seemingly answered, and everything changed. The family rarely received mail, so when a letter addressed to a Mr. Osma Harrell showed up on a particularly warm Tuesday evening, the Harrell family was bewildered. Ms. Harrell originally assumed her youngest son had gotten into trouble and was about to yell at him when Mr. Harrell let out a whoop of joy. Some mysterious benefactor, potentially an anonymous relative or friend, had mailed the Harrells a hefty check intended to cover school expenses for Osma to attend the University of Georgia.

Osma wholeheartedly embraced this opportunity and was able to pull himself from poverty. He gave away large portions of his money to those in need, and before his death at 72, he set up a free medical clinic for people who couldn’t afford medical care in an empty building adjoining the parking lot of his church. Although he also sent money back to his family at every opportunity he could, by the time he could afford to educate his family, his siblings already had families of their own. Osma was the only one who ever truly made it out of that town.

Osma is my mom’s grandfather. His education had a bigger impact on his legacy than anyone could have ever predicted. He was extremely fortunate to receive this opportunity, but his hard work and continued generosity set up his future family for success. From dirt roads in Georgia to running his own practice, his infectious love for people and healthcare earned him his long-standing nickname, Doc. His success allowed his four sons and daughter to attend college, and he put all of the rest of his money in an account to help pay for the college education of all fifteen of his grandchildren.

The importance of a solid education has been instilled in my brain as the key to a successful future. But to me, the story of my great-grandfather’s life extends beyond education. Osma was a person of grit and bravery, but his hard work would have been nothing without a stranger’s selfless action. The fact that someone could give up so much of their own finances to give a child a chance at a better future, has always really touched me.

My grandparents built upon this selflessness. Every few years our grandparents will give each of us children one hundred dollars to give to a charity of our choice. This gift always intrigued me, and I often wondered why they didn’t just give the money to a few charities themselves. In the past few years, however, I have come to the conclusion that they did this to further instill in us kids the importance of helping others.

The experiences I shared, and the stories I was told growing up truly opened my eyes to the vast influence of a kind action; through these donations, my grandparents emphasized to me the importance of helping others, and because of this, in recent years, I have begun to volunteer more of my time and energy in environments where people face adversity. The Prison Book Program is an outlet where I push myself to live beyond my own bubble and use my privilege to improve the lives of prisoners. Responding to gratitude-filled letters from imprisoned people, and personally picking books for them to read has been a hugely fulfilling and humbling experience. My family’s and my own interest in helping others stems from stories like Osma’s in which we saw the true impact of a selfless action, and I hope to continue to bring a piece of my family’s humility with me to every challenge or experience I face.

WORK TILL YOU DROP

Sadie SaaronyWe carry our books, pencils, computers, and notebooks. Our bags hold it all together.

We carry our heavy backpacks through the halls. Our shoulders can bear the weight.

We carry our knowledge, intuition, and curiosity. Our minds keep it vivid and safe.

We carry our grades, maintaining our A-statuses. Our willpower keeps our determination strong.

We carry our heads high and proud, but my neck is feeling sore and

We carry our bodies, walking with one foot in front of the other, but my legs are beginning to ache and

I carry all my emotions, calmly and quietly, but I’m finding it harder to keep them in and

I carry–Oh, I dropped it.

wachusett mountain Izzy Ding

i am one of the tiny people i saw on the chairlift. standing on top of the sunset, i drink the icy air and forget.

head empty, only adrenaline and rapid heartbeats. like an unfinished dream. the bottom of hitchcock is nowhere to be seen.

perhaps it’s my muscle memory or survival instinct because my arms are now pushing on the poles as my skied, too-long feet tilt downward. somehow, i live. as if i’ve done this for years, the arches of my feet take turns tilting inward and i coast down, skidding up a fine powder of ice and snow behind me.

but the story’s too boring, so i slowly lose control as my path narrows and the people multiply. suddenly, i’m still as the world turns to a blur.

wind whips my exposed skin like an ice-cold sheet of sandpaper and no amount of swerving will allay this impending doom.

yet joyous screams from the id escape my mouth and i’m free.

the steel chains, my superego tries so hard to latch on, but i’m too fast and they slide off my invincible body.

perhaps this is what euphoria feels like. i hope so.

STAR-FACED

Jasmine QianUpon the salt of the seas’ wide mouths, a stitch of stars and the swell of tide, I am taught the means to float.

Dawn cracks night’s canvas and the stars splash, like the sky is of water, and we, of air.

What ease it would be to fall into blue, to not know we are dying until already dead, to not know we are drowning until we have no breath.

It had been bound to happen eventually. The ventilation was poor, and it had not yet been discovered that lead was poisonous. None of this occurred to Perenelle until the name Nicolas Flamel had long passed into legend, and the Philosopher’s Stone was considered the domain of crackpots. At the time, Perenelle, at the age of twentyfour, was mostly concerned with whether her husband would want his supper brought to his laboratory while he was working.

Perenelle had cooked one of his favorites that night. It was a fileted haddock drizzled with the juice of a lemon she’d happened upon at the market that morning. Perenelle wiped her hands on her skirt. She finished tidying up. She hung her prized iron skillet on its hook. Perenelle went outside to toss seed to the chickens, who had been clucking impatiently for the past half-hour. When she came back inside, the haddock was still laying on its wooden trencher. Its beady eye regarded Perenelle with disdain. Perenelle hurried to cover it up with a cloth before it cooled, though her husband probably wouldn’t care anyway. She glanced out the window. The sky was beginning to turn orange. Perenelle deliberated for a moment. Then she picked up the trencher and marched out the door.

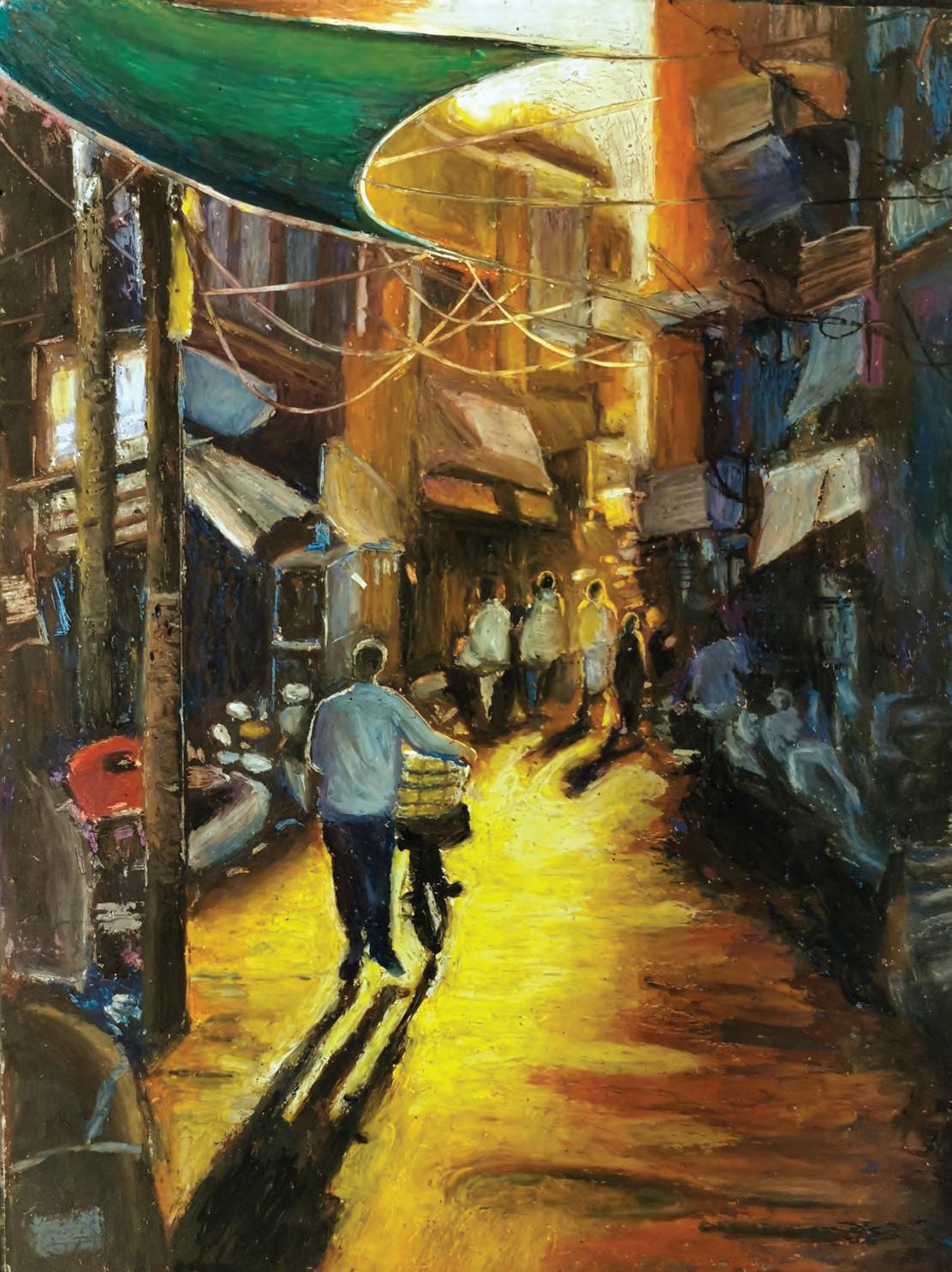

A cart rattled by. A baby wailed. The church bells clanged. Vendors hollered to passers-by. Perenelle twitched and drew her hood up. She kept her head down and stepped into the mud.

It was a balmy day in early summer, but late enough in the day that the light breeze made Perenelle shiver. She covered her husband’s dinner with the corner of her cloak to shield the smell from the stray dogs that had begun to gather. The boldest of them came a little too close for Perenelle’s liking. She strode on. It followed. She walked faster.

Two streets later, Perenelle turned into an alleyway. At the end was a squat stone building with a heavy wooden door. She knew he didn’t like to be disrupted. She knocked anyway. There was no answer. She stepped closer. Inside, there was a faint bubbling. She knocked again, more firmly. Nothing. It wasn’t unusual for Nicolas to completely disregard her presence, but with the door in the way, he wouldn’t be able to tell it was someone so inconsequential as his much-younger wife.

Perenelle cleared her throat. “Nicolas?” Again, silence.

In her distraction, the dog made a try for the haddock. She lifted it over her head and shoved the dog away with her foot. It fled, yipping. Perenelle straightened her clothes, unlatched the door, and shouldered it open. As she stumbled into the room, she started coughing. A sickly, sweet smell suffocated the entire room. Perenelle put her sleeve over her face and shuffled deeper inside. The room was dimly lit. A few torches were bracketed along the wall, and several candles were scattered here and there. The hearth roared beneath a large pot. Flasks and papers were scattered across heavy, stained wooden tables.

“Nic –” Perenelle broke off spluttering. She moved slowly throughout the room, clutching the trencher to her ribcage.

A book lay open on the table. Its pages contained intricate, circular diagrams and letters Perenelle didn’t recognize. A shiny silver powder sat in a bowl next to it, labeled “Stage 2.” An empty bowl lay on its side, likewise labeled “Stage 3.” Nicolas liked to indulge his paranoia by ensuring he was the only one who could decipher his work.

Perenelle picked her way towards the fire. The cloying scent intensified as she drew nearer. She peered into the cauldron. Inside was a metallic, dark gray substance flecked with gold. It bubbled lethargically. Each subsequent burst of liquid magnified her headache.

She stepped back. Her heel bumped into something soft. Perenelle turned. The thing she had almost stepped on was shrouded in shadow. She dropped her sleeve from her face, shifted her haddock, and picked up a candle from the table. Perenelle knelt down and almost dripped hot wax on her limp husband.

“Nicolas?” Perenelle’s hands were full, so she nudged him with her knee. He didn’t move. She nudged him harder. He remained unresponsive. Perenelle set the candle down on the floor and tapped Nicolas’s face. She felt his brow. It was warm and a little clammy. Perenelle placed her hand under his nostrils. He wasn’t breathing. She gently patted over his body. No wounds. She lifted up his head. The back of his skull was perfectly intact.

Something glinted on the floor near the fireplace. It was a rock, deep-red, pitted, and angular. As Perenelle watched, the rock slowly faded to black. She picked it up. It was warm to the touch and a little rough. It wasn’t sharp enough to cause any damage.

Perenelle shifted back to her dead husband. Nicolas’s eyes had landed closed. Even so, his brow was knit and his mouth set. His expression created wrinkles that betrayed his real age, counteracting the effects of his alchemical breakthroughs. Perenelle held the stone up to his face. She pressed it into his forehead, then his cheek, then his chest. Nothing happened.

Perenelle did the only thing she could do, as a woman who was about to inherit a small fortune upon being widowed for the third time. She stood up, threw the contents of every little bowl into the fire, gathered every loose paper, closed every notebook, hid them beneath a table draped in cloth, and stuffed the stone down her shirt. She clutched her husband’s dinner tighter and knelt down next to him again. She raked a hand through her hair to dishevel it a little. Then, Perenelle screamed.

Such a sound was not unusual in most of Paris, but in this district, it would certainly be noted. And it was. Perenelle continued to shriek, staring up at the ceiling in concentration as fists pounded on that huge wooden door.

The door appeared to be stuck. Perenelle added in a sob for good measure. She raised a hand to her chest and felt where the stone was pressed up against her skin. Even as Nicolas’s wife, she didn’t know much more than the rumor-mongers. She didn’t know if anyone but Nicolas could use the stone, or if he could use it on anyone else. Was it that he didn’t want her to be frozen at twenty-four forever? Or was it that he didn’t want to be tied to her forever?

It didn’t matter. Perenelle hunched herself over, but not enough to squish the fish. She tensed her shoulders so hard they started shaking and wailed again. The door slammed open and hit the wall. In rushed Alain, a stocky young man who ran the inn down the street.

“Madame Flamel!” he called. “Somethin’ wrong?”

Perenelle groaned in response. The fumes from the fire were making her feel dizzy. The smell of the haddock only made her more nauseated, but she couldn’t let go of it.

Alain knelt beside her. “Oh, merciful Lord…” he murmured. “Come on, lovely. Let’s get you outta here.” He wrapped an arm around Perenelle’s shoulders. Perenelle stiffened at the contact, but allowed herself to be pulled up. Every step felt shaky. When they reached the door, she allowed herself to breathe again. Instead of overbearing sweetness, she smelled horse manure. As Alain gingerly let go of Perenelle, she listed sideways, let go of the haddock, and fell directly into the wall.

By the next af ternoon, Perenelle had recovered from whatever had come over her the previous day. Grief, Alain had called it, panic arising from the third sudden death of her third supposed life partner. Women weren’t meant to be left alone like that – except, Perenelle’s first two husbands hadn’t exactly left her by dying; it was the other way around.

It had been lead poisoning, Perenelle determined some six hundred years later. Despite having spent the better part of said six hundred years in solitude, Perenelle had never quite thought herself alone. Over the centuries, many things remained constant – greed, love, and the mild taste of haddock. Besides, she had the memory of her three dead husbands to chide, mock, and ignore her, respectively. She’d never wanted to share her third husband’s discovery with anyone – the Elixir of Life, the Philosopher’s Stone, the Fountain of Youth –whatever people were calling it these days. The world simply couldn’t be trusted with it.

Instead, Perenelle hummed to herself as she squeezed the juice of her favorite variety of lemon into a bowl. The haddock sizzled on the stove to her left. Once the fish was done, she brushed it with the marinade. Perenelle dumped the pan in the dishwasher and sat down to eat dinner alone.

MY TEARS FLOW ENDLESSLY OVER AND OVER

Asumi YazakiMy tears flow endlessly over and over.

I pass through airport security with my passport and student visa.

The distance is getting further and further.

I will no longer see them if I turn that corner.

Goodbye to my sister’s innocent smiles. Goodbye to my mom’s warm miso soup. Goodbye to my dad’s annoying jokes.

I can still see them waving their hands.

My tears flow endlessly over and over.

But I wipe my tears and turn the corner.

STAFF PAGE

CO-EDITORS IN CHIEF:

Qihan (Angel) Fu ‘24

Yufei (Caitlin) Kuang ‘24

ART EDITORS:

Mengqi (Sophia) Gu ‘24

Aylin Hamzaogullari ‘24

LIT EDITORS:

May Gong ‘24

Xiangyi (Nina) Wang ‘24

EVENT COORDINATORS:

Sophia Bowman ‘26

Yvonne Hao ‘25

STAFF:

Jenni Ding ‘26

Arya Lal ‘25

Sophia (Micheline) Reid ‘26

Penny Wei ‘27

Genevieve Wu ‘26

FACULTY ADVISORS:

Mary Ann McQuillan

Julia Ryan