6 minute read

13 Trotting Horse

Trotting Horse

13

Advertisement

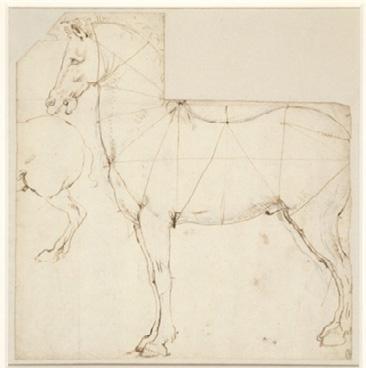

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A horse in profile divided by lines, pen and ink over black chalk, c. 1480. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A horse in left profile with measure-ments, c. 1490 both Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) Studies for an equestrian monument, pen and ink over black chalk, c. 1517 – 18. Recto: a study of a horse, moving in profile to the right, and two studies of horses moving to the right, seen in three- quarter view from the rear. Verso: a study of a horse in profile to the left, and an equestrian figure riding in profile to the right, his right arm outstretched behind, and a fluttering cloak. c. 1517 – 18, Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016.

13

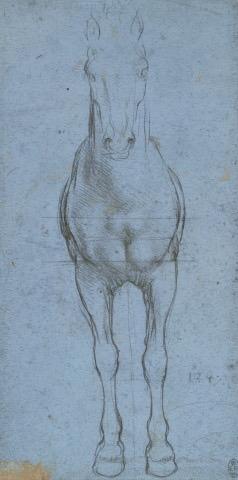

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A quick study for a horse walking in profile to the left, pen and ink, c. 1490. Fragment from the Codex Atlanticus, 147 recto-b; Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016 Leonardo da Vinci, (1452 – 1519) A Horse divided by lines, metalpoint on blue paper, c. 1490

Leonardo da Vinci, (1452 – 1519) A horse in profile and from the front, c. 1490, metal- point on blue paper, both Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016

Trotting Horse

TROTTING HORSE

Italian (Florence or Milan) Circa 1500

Bronze, direct unique cast Height 27.8, length 31.5 cm

Provenance: Marczell Nemes Collection, acquired at auction at Mensing, Amsterdam, 13–14 November 1928, lot no. 113 (as being by a ‘Milanese Master’) for 7140 Reichsmarks by Heinrich Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon; thereafter through the family until 2006

Related literature:

xxx

The horse was produced using the direct casting method with which a figure is modelled in wax directly on a so-called casting core. An outer casting mould, a so-called investment, is then placed over the wax and held in place by core pins. This is followed by the firing process during which the wax runs out. Afterwards, bronze is poured into the hollow form created. The direct casting method has certain characteristics such as somewhat more solid walls of slightly varying thicknesses. In the case of our horse sculpture, an original, corrected and barely visible casting error has been identified behind the right ear. This was probably where a large part of the casting core was removed. No other corrections are discernible.

Indicative of the anonymous artist’s great talent are the outstanding, individual modelling of the mane and tail as well as the unusually realistic depiction of the hooves. In addition, the whole body has a delicately hammered surface structure. As the design, skilled production and artistic quality of this horse are exquisite it must have been created in the workshop or in the vicinity of one of the great Renaissance masters. In the Renaissance there were only a few statues of mounted riders or horses considered as prototypes. These include the Quadriga, comprising four gilded bronze horses, taken from Constantinople in 1204 for St. Mark’s in Venice and the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome dating from Antiquity. In 1453 Donatello completed his bronze equestrian statue of the mercenary leader Gattamelata and, up until his death in 1488, Andrea del Verrochio had been working for ten years on a memorial to the condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni. This was first completed and cast in 1496 by another sculptor, Alessandro Leopardi. All of these equestrian figures, however, stand on three legs, not least of all to provide stability. What makes our horse so special is its elegant stride, with a diametrically opposed rear and front leg raised at the same time.

The movement of this step is reminiscent of the so-called piaffe in dressage that was already being taught in the Renaissance. The ‘Regisole’ (Sun King) monument in Pavia, that also dated from Antiquity but was destroyed in 1796, was probably the only one also showing two legs raised simultaneously. In looking for an artist who could have manufactured our bronze, one soon arrives at the circle of Leonardo da Vinci. Throughout his life Leonardo was preoccupied with creating the most anatomically precise depiction of a horse possible and made numerous sketches and designs of horses in various positions and gaits. The bronze cast for an equestrian statue to honour Francesco Sforza in Milan, in particular, for which Sforza’s sons sought an appropriate master of his craft after 1473, was a challenge to the universal genius.

In 1482 Leonardo writes to Lodovico Sforza in Milan offering his services as an architect of fortresses but also mentions the ‘bronze horse’: “... to [mark] the immortal glory and in eternal honour of your father as well as of the virtuous House of Sforza.” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 391r-a, cited in: Ladislao Reti (ed.), Leonardo. Künstler, Forscher, Magier, Frankfurt a. M., 1974, p. 88). Leonardo is called to the court and remains there for sixteen years.

13

During this period he repeatedly works on a design for the equestrian memorial that, at Ludovico Sforza’s request, was then to be much larger than life-size with a height of seven metres. Numerous studies and sketches still exist that interestingly also show the piaffe step sequence. Together with Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Leonardo visits the city of Pavia in 1490 where he is deeply impressed by the so-called ‘Regisole’ equestrian monument mentioned above. He writes: ”What one has to marvel at in particular about the horse in Pavia is its movement … its trot is precisely like the trot of a living horse.” (Cited in Reti, 1974, p. 94). A drawing is held at Windsor Castle that Leonardo could have made of this monument. It shows a trotting horse that is lifting its front left and rear right legs. After seeing the ‘Regisole’, Leonardo switches from his original design for a rearing horse back to one trotting. He develops innovative casting and modelling methods in order to be able to cast a horse four times its real size. He describes this in detail in the Codex Madrid II, which he illustrates with drawings. He is, however, never able to turn his ingenious concept into reality. The bronze for the cast that had already been delivered is used instead to make cannons to fight the French King Charles VIII. After Ludovico Sforza’s defeat, Leonardo leaves Milan in 1500.

It is possible that Leonardo also created a bronze model of a striding horse with which our unknown artist may have been familiar. It is known, for example, that Leoni Leoni (1509 – 1590) of Milan owned several of Leonardos horse bozzetti. Whether a comparable horse was among these can no longer be verified. The lively execution of its step, the precisely modelled head with its open mouth and snorting nostrils, as well as the detailing of the hooves suggest an extremely talented artist. These could include a master sculptor in the circle of the Court of Milan or a successor to Andrea del Verrocchio of Florence. The technical execution of this single cast could only been achieved by an experienced craftsman who certainly would not have been working on his own but would have received an apprenticeship within the circle of artists already mentioned.