9 minute read

MADE IN COS: Locals create beauty — and save lives

MADE IN

Advertisement

Colorado Springs Springs

Local artists, artisans and fabricators create beauty and save lives

BY JEANNE DAVANT | jdavant@sixty35media.org

THE 200 SKILLED WORKERS AT

Collins Aerospace have 702 reasons to be proud of the work they do.

That’s how many lives their product — an ejection seat for fighter, bomber and trainer aircraft — has saved.

The ACES 5 ejection seat is the newest iteration of the product line first deployed by Collins in 1978 — and this year, it made the Colorado Chamber of Commerce’s Top 10 list of the coolest products made in Colorado.

The same kind of care and attention to detail characterizes the work of artisans at Ranchlands Mercantile, a leather shop at the Chico Basin Ranch southeast of Colorado Springs.

Among Ranchlands Mercantile’s best-selling products are belts, bracelets and a crossbody satchel designed like a cowboy’s saddlebag.

The high quality of the carved, tooled and woven leather pieces won the notice of editors at Vogue magazine, which featured the shop’s work in a 2019 article.

Jannine Scott’s work with glass is as meticulous as Ranchlands’ leather work.

In her studio at the Manitou Art Center, Scott uses a blowtorch to bend and shape molten glass into items from small beads to large, complex wall pieces.

Through her business, J9 Glass, Scott has sold her pieces at boutiques, galleries and art festivals across the country and has shown her work at venues like the Sangre De Cristo Arts and Conference Center in Pueblo alongside the works of renowned artists like Dale Chihuly.

Protecting pilots

“We are in the business of saving lives,” says Don Borchelt, Collins Aerospace’s director of business development, sales and marketing for the ejection seat. “It’s a very meaningful job for the folks who make the seats we’re delivering for the service men and women around the world — not just in America, but in all of the countries that also fly on ACES ejection seats.”

Collins Aerospace is one of the largest suppliers of aerospace and defense products in the world. Headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, it’s a subsidiary of Raytheon Technologies.

The unit that makes the ejection seat in Collins’ plant on Aeroplaza Drive in Colorado Springs is part of Collins’ Mission Systems portfolio.

The ejection seat performs an extremely complex sequence of operations when a pilot makes the decision to abandon an aircraft in an emergency, Borchelt says.

Pulling the seat’s ejection handles “starts a fully automatic process of exquisitely timed actions that take place in about a second to a second and a half to get the air crew safely out of the airplane and bring them down into a main recovery parachute,” he says.

This complex technology is the work of “our very passionate engineers here and in our sister facility in Fairfield, California, that makes the rockets and pyrotechnics that make the ejection seat rocket out of the airplane,” he says.

The ACES 5 incorporates innovations applied to the original design, the ACES II, which is still widely in use in military aircraft around the world, Borchelt says. The improvements include a passive arm and leg restraint system that helps prevent injuries and a new main recovery parachute and drogue parachute, which slows down the main parachute.

The unit that produces the ejection seats moved into the Aeroplaza facility just under three years ago, he says. It needed more space to fulfill a multiyear contract with the U.S. Air Force, which is replacing all the ACES II seats in its aircraft over the next seven years — roughly 2,500 ejection seats.

Borchelt says the company is hiring additional workers to fabricate the seats.

Abby Santurbane works in the leather shop at Chico Basin Ranch. The shop is one of several side enterprises at the ranch. The ranch’s livestock operation is its main business, but sales of premium leather goods help tide it over in tough economic times.

Premium leather goods

Ranch life isn’t as dramatic as it’s portrayed in the popular TV show Yellowstone, says Tess Leach, head of business development for Ranchlands.

Leach’s dad, Duke Phillips, grew up on a ranch in Mexico.

Phillips went on to found Ranchlands, a ranch management company that operates large-scale cattle and bison ranches in Colorado, New Mexico, Texas and Wyoming.

Ranchlands owns one of the ranches and partners with private owners to run livestock operations on the others. In Colorado, Chico Basin Ranch is owned by the state of Colorado. The Zapata Ranch in the San Luis Valley is owned by the Nature Conservancy. Ranching is the main business, but Phillips and his family have created complementary enterprises. One is hospitality — they host individuals and families who can participate in a range of activities from simply enjoying the natural surroundings to working alongside wranglers and ranch staff. They also book meetings, retreats and special events like a sandhill crane weekend, happening March 10-12 this year; lead ecotours and hunting and fishing expeditions; and produce and sell ranchthemed leather goods.

The leather products are produced at Chico Basin and sold primarily on the ranchlands. com website but also are featured at Ranchlands Mercantile at Chico Basin and a brickand-mortar store at Zapata Ranch.

Phillips’ leatherworking skills came in handy on the ranches for repairing bridles, tack and the like, but he also made gifts such as leather bags for Leach, her sister and her mother.

In 2015, what was a hobby became an enterprise. The Phillips family partnered with Nest, a nonprofit that works with fledgling artisan businesses, which helped formalize designs and set up the shop.

Leach’s sister-in-law Madi Phillips, who learned leather craft from her father-in-law, is the head maker and runs the shop along with Leach.

Besides the crossbody saddlebag, one of the shop’s big sellers is a billy bag — a semicircular pouch meant to hold a tea canister. Phillips and his son, also named Duke, got the idea for these bags while working on ranches in Australia.

These products, which are lined with a second layer of leather, are designed to last a lifetime.

Several years ago, a guest at the ranch contacted someone they knew at Vogue magazine about the unique leather bags.

The result was an August 2019 article and photo spread titled “Inside the Leather Shop at Colorado Springs’ Ranchlands, Where American Craft Meets Modern Design.”

The writer, Brooke Bobb, had this to say about Ranchlands’ leather enterprise: “Their new collection of tanned leather satchels would look just as cool walking through downtown Manhattan as on horseback.”

Our model of ranching is looking at the land as a

MULTIDIMENSIONAL RESOURCE. — Tess Leach

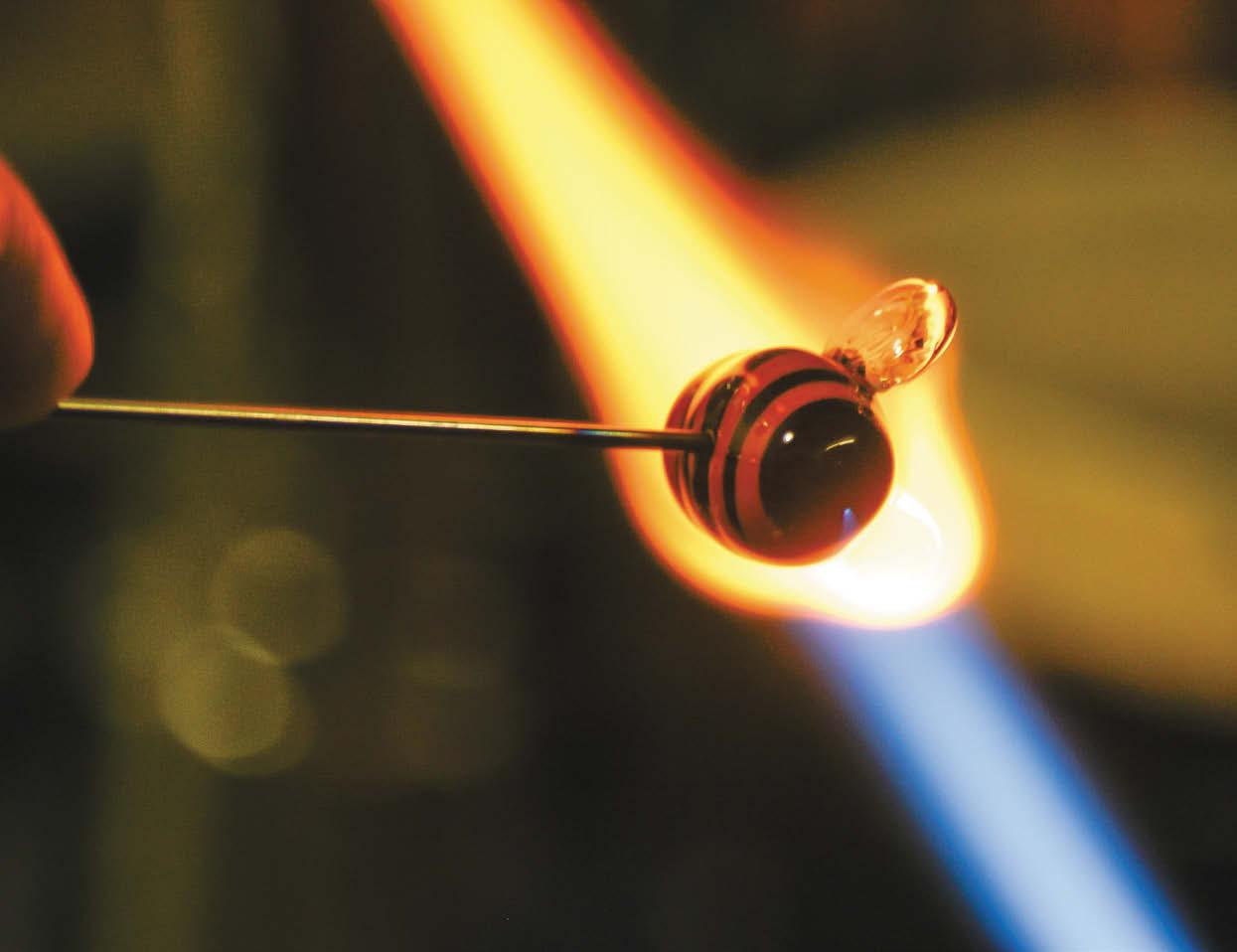

Jannine Scott melts a glass rod with a blowtorch in her studio at the Manitou Art Center. Bryan Oller Scott uses a process called lampworking to shape items from beads to large installations.

Fire and glass

Jannine Scott manipulates molten glass with a blowtorch, a process called lampworking, to make exuberant and colorful items like hair ornaments, glass straws, decorative plant pokers, pipes and glass neck chains, as well as ornate wall pieces.

She uses various techniques such as latticino, a traditional Italian art glass method, but what makes her work different is the hot strip method she uses to create the small bees, ladybugs and clouds puking rainbows that embellish her pieces. Executing the hot strip technique involves many time-consuming and complex steps, and Scott has mastered it.

She was introduced to lampworking by a bead maker in Dillon, Colorado, while she was working in Vail, and opened her first studio in Red Cliff, Colorado, in 1999.

Scott later lived in Oregon, near Medford. and opened Alpine River Glassworks. She sold her work at arts and crafts shows in Sedona, Arizona; Napa Valley, California; and other locations across the country. She moved back to Colorado in 2005, landing in Manitou Springs.

For years, her art glass work was part time.

After relocating to Manitou, she managed Safron, a clothing and accessory boutique.

Now, J9 Glass is her sole focus. Scott has begun attending shows again after a pandemic layoff, as well as marketing her work through the Manitou Made website.

Most of her work time is spent making the smaller items, like the spiral hair noodles that have been her best seller for 20 years, and plant pokers adorned with bees.

Besides the usual business practices, Scott notes that entering art shows requires entry fees, additional licensing and tax procedures that must be set up in advance — and, she says, the galleries take up to half of the proceeds of sales.

Scott’s goal is to boost sales of her larger, sculptural pieces, which she describes as “mixed media pieces with glass coming out of them three dimensionally.”

While Scott doesn’t subscribe to the starving artist model, she says money isn’t the only object.

“I feel like the things that you gain are unique experiences that normal people don’t get to experience, like large projects together with other artists to make things just for the sake of making it,” she says. “Knowing people that do amazing things and being around them all the time is really amazing.”