5 minute read

Dr. Michelle Arnold: Colostrum and the Newborn Calf

Colostrum and the Newborn Calf

Dr. Michelle Arnold UK Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Early and adequate consumption of highquality colostrum is considered the single most important event in determining the future health and survival of the newborn calf. “Colostrum” is the first milk produced by the cow after the birth of her calf. It is an essential source of dietary nutrients and, more importantly, it contains the antibodies the newborn calf needs for protection from disease until its own immune system is functional. A newborn calf’s small intestine is designed to temporarily allow the absorption of colostral antibodies or “immunoglobulins”, directly into the bloodstream. This is called “passive transfer” of immunity and only occurs during the first 24 hours after birth. Colostrum contains several different types of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM), but IgG accounts for roughly 85% of the total volume. IgG absorption is most efficient in the first 4 hours of life, it declines rapidly after 12 hours and, at 24 hours, the gut is completely “closed” and there is no more IgG absorption into the circulation after that time. “Failure of passive transfer” of immunity (also called “FPT”) occurs when a calf does not absorb enough IgG. FPT has been linked with increased calf morbidity (sickness), mortality (death), and a reduction in calf growth rate and feed efficiency. It is estimated that approximately a third of calf deaths in the first three weeks of life are due to inadequate colostrum intake. Any factors that prolong the time between birth and first suckling such as poor mothering ability (heifers), poor udder and teat anatomy, and dystocia (difficult birth) will increase the chances of FPT. Calves born in very cold weather or those experiencing a difficult, prolonged birth often need to be hand fed promptly due to their delayed ability to stand and nurse.

The most important factor affecting colostrum absorption efficiency is the age of the calf. The goal is for beef calves to stand and nurse within 1-2 hours after birth and again by 6 hours at the latest. If this does not occur, the dam should be restrained, and the calf helped to find and suckle the teat. If the calf is unwilling or unable to suckle, the cow should be milked by hand and the calf fed colostrum with a bottle or an esophageal feeder. It is generally accepted that either method of feeding achieves acceptable results as long as a sufficient volume is consumed. Although there is quite a bit of variation in colostrum from cow to cow, studies have found that when a beef calf receives 5% of its birth weight in colostrum within 1 hour of birth (1 quart colostrum per 43# body weight) with subsequent suckling of dam or receives a 2nd feeding within 6 hours of age results in adequate passive immunity. An excellent video “How to Feed Newborn Calves (esophageal feeding)” is available on the Beef Cattle Research Council website at https://www.beefresearch.ca/blog/imagevideo-library/#calving along with many other educational videos. If using an esophageal feeder, make sure it is only used to feed colostrum to newborns and a separate feeder is used to treat scouring calves with electrolytes. If the dam does not have enough colostrum or it is not possible to milk the dam, the next best option is to use fresh or frozen colostrum harvested from a mature, healthy, and wellvaccinated herd mate. Older cows tend to have “better” colostrum than first calf heifers, as

they have been exposed to a greater number of pathogens (bad bugs that cause disease) during their lifetimes and so make more antibodies and a greater variety of them. To collect and freeze high quality colostrum, milk the cow within 1-2 hours after calving with a maximum delay of 6 hours. The concentration of IgG is highest immediately after calving but decreases over time. Make sure the teats are clean prior to milking to minimize bacterial contamination. Bacteria will bind up the immunoglobulins in the gut so they do not pass into the bloodstream and contaminated colostrum may contain infectious agents that cause diarrhea and septicemia such as Salmonella and E. coli. If not fed immediately, colostrum should be frozen in 1-2 quart containers or refrigerated within the hour. Frozen samples may be used for up to one year provided there is no freezing and thawing. The IgG in colostrum is considered stable in the refrigerator for approximately 1 week although bacteria counts may reach unacceptable levels if not cooled quickly enough. Immunoglobulins are sensitive to very high temperatures so a warm water bath (110 degrees) and frequent stirring, rather than a microwave, should be used when thawing frozen colostrum. Producers should be prepared for times when clean, high-quality colostrum is unavailable. Commercially available colostrum products are labeled as either a colostrum “supplement” or a colostrum “replacement”. A colostrum replacement product is designed to be fed when no maternal colostrum is available. Replacement products should contain at least 100-150 grams of Bovine IgG, protein, minerals, vitamins, and energy. This should not be confused with a colostrum supplement product that is designed to be fed in addition to and after natural colostrum. Colostrum supplements are significantly less expensive than replacement products because they contain less than 100 mg IgG per dose and have no added nutritional value. Producers should use supplements to fortify poor-quality colostrum, or when inadequate amounts of fresh or frozen colostrum exist.

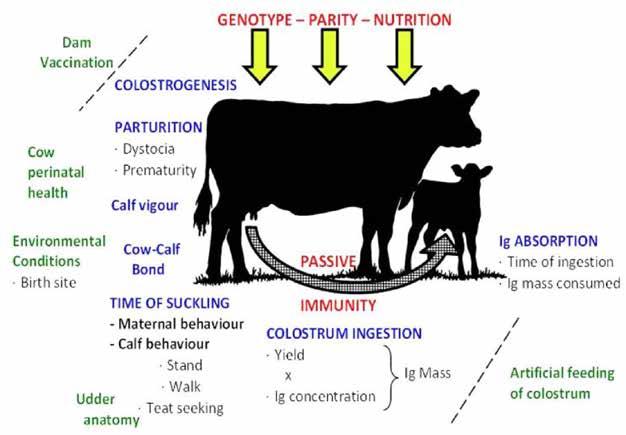

Figure 1 is a summary of the many factors affecting passive immunity in calves. The factors in green print (dam vaccination, cow perinatal health, environmental conditions, udder anatomy, and artificial feeding of colostrum) are factors the beef producer has at least some control over. The factors in red print (genotype, parity and nutrition) are the important “cow” factors prior to labor and delivery. The factors in blue print (colostrogenesis, parturition, calf vigor, cow-calf bonding, time of suckling, colostrum ingestion and IgG absorption) are the critical elements that must take place at birth for successful passive transfer of immunity.