8 minute read

Pac-10s 1980 When St. Helens Blew

from Spring 2021

Monday morning wake up call. Louise (Hill) Thomas bought a copy of this Oregonian before we left Portland. Her parents and two sisters had recently moved to Vader, a few miles north of the I-5 Toutle River Bridge.

PAC-10S 1980

Advertisement

WHEN ST. HELENS BLEW

The 1980 Pac-10s were raced at Redwood Shores, 10 miles southeast of San Francisco International Airport on an attractive but narrow course suitable only for dual-race format. Finals were on Sunday, May 18. First up, 8:30am, the Men’s Heavy 8: Washington vs California. UW coach Dick Erickson recalled race conditions as “perfect.” Hint of things to come: the Huskies borrowed a Carbocraft and Karlisch oars from UBC. This was the first Husky crew that ever raced without Pocock equipment.

When the crews left the line, the Bears were favored. The Huskies trailed by a seat at 500 meters. When Cal made a move, the Huskies, under-stroking their opponent, parried successfully. At the 1,200-meter mark, the crews were trading bow balls. UW prevailed by under one second. The finish time of 5:42.17 beat the course record by 10 seconds. Minutes earlier, 700 miles north of the course, Mount St. Helens had blown its stack.

Thirty-year-old US Geological Survey scientist David Johnston was a Husky Geology PhD and one of many scientists at the USGS Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park, minutes from Redwood Shores. Assigned to the St. Helens monitoring team, Johnston believed scientists should accept risks to mitigate natural disasters. His work, and that of colleagues, persuaded authorities to close the mountain two and a half weeks before it erupted, an unpopular decision that saved thousands of lives.

On Sunday morning, Johnston was measuring volcanic emissions from an observation post considered acceptably safe, six miles north of the summit. At 8:32am, in a voice described as “excited, not frightened” by the lone radio operator who heard it, he radioed: “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!” Moments later Johnston died in a pyroclastic flow or surge: a super-dense cloud of volcanic gasses, pulverized stone, ash and magma. Most pyroclastic clouds are gravity-driven and average around 65 mph. Propelled by an explosive blast wave, the flow that killed Johnston reached speeds of 670 mph and temperatures of 680°F. (“PDC,” for Pyroclastic Density Current, is geological shorthand for these emissions, which may be hot or cold. This was a cold PDC. Thumbs up to Susan Ernsdorff (’80) for that clarification.)

First, a magnitude 5.2 quake dislodged the peak, triggering the largest landslide in recorded history. The debris avalanche exposed the cryptodome, a reservoir of semi-molten magma rich with compressed gasses that had been growing since March. Its massive lid removed, the cryptodome exploded, uncorking the

WHAT EXACTLY HAPPENED?

the volcanic vent. Almost instantly, rising magma reached groundwater. The titanic fresh-lit steam-fired blast furnace produced a lateral eruption, kicking the already fast-moving landslide in the behind. The top 1,300 feet of the cone partly slid, partly flew north, leaving a mile-wide horseshoe-shaped crater. The mixture of rock, tephra and ice was estimated at seven-tenths of a cubic mile.

Dave Emigh (rowed 1972–1973; Frosh Coach 1976–1979) was working at the Boeing plant in Everett at the time. He wrote: “For weeks prior to the eruption, Boeing test pilots would try to fly around St. Helens. Their descriptions of steam plumes, ash columns, gray fallout on the peak, would circulate through the engineering department.”

On the morning of the 18th, Emigh was his leaving his Everett home for rowing practice at LWRC. Hearing a boom, he thought someone crashed into his garage. Then he heard an echo. The second boom was louder than the first, and it wasn’t an echo: it was Spirit Lake and the Toutle River, blanketed by pyroclastic flow, exploding in a cloud of steam. Before sunset, 7,000 deer, elk and bear; 250 homes; 230 square miles of standing timber; 185 miles of highway; 57 human beings; 47 bridges and 15 miles of railway were gone.

For the Cougs back at Redwood Shores, the first hint of trouble ahead came via shop talk. A puzzled Dick Erickson told Coach Struckmeyer that his usual post-race chat with the Seattle Times sports desk never happened: “Sorry, can’t talk right now. The mountain just blew. Click.” More specific, and increasingly alarming, information accumulated gradually as the day rolled on.

1980 PAC-10 Regatta Program Cover

LONG SLOG HOME TO CLOSED WEEK

By 1:00pm, the show was over. The Men’s Light 8 were the great consolation, trailing only the Dawgs. The men’s Heavy 8 finished fifth behind UW, Cal, OSU and UCLA.

Equipment loaded, two chartered Greyhound Scenicruisers hauled the Cougar rowers a few minutes south to Menlo Park, where Bill and Jeanne Lane, parents of JV oar Bob Lane and publishers of Sunset Magazine, treated the entire squad to a lavish buffet. Sunset’s “Laboratory of Western Living” was a park-like nine-acre campus a few blocks from David Johnston’s USGS office. Coach Ken and co-pilot JV Coach Doug Engle (rowed 1975–79) left the party early in the signature green Chevy pickup, shells and blades in tow. Splendid late lunch in California sunshine concluded, the highway stages loaded once more and commenced the 900-mile journey north.

The convoy next rendezvoused around 6:00pm at an enormous truck stop near Dunnigan, CA. There, according to several different rowers, we first learned St. Helens had erupted. A convenience store cashier ringing up mass quantities of beer and munchies asked our destination and replied we might have trouble getting home. Our response was bemused skepticism. We’d been hearing false alarms for a couple of months.

The next leg-stretcher, two hours plus north, was likely at a big I-5 rest stop close to Redding, CA. While carefree bus riders were doing the party-hearty, Ken and Doug were navigating the shell trailer and listening to the radio. It was likely here Ken advised us that main routes to eastern Washington were closed. According to Women’s Coach Gene Dowers: “It wasn’t until well after dark that we knew we wouldn’t be able to go back to Pullman. Ken was more worried than I’d ever seen him.”

Around six in the morning, exhausted Cougs flooded the Greyhound bus terminal in Portland, the coming hours of their journey now a completely open question. Many tried to sleep on uncomfortable plastic chairs. Thanks (probably) to the efforts of Ken Abbey back in Pullman, arrangements had already been made for the team to bivouac at Husky Hilton. At daylight, we would drive due north for Seattle, gambling that the I-5 bridge over the Toutle River would be open and we would be permitted to cross.

By 9:00am on Monday, May 19, barely 24 hours past the most violent phase of the eruption, we boarded our buses and got back on I-5. East of the mountain, the big concern was volcanic ash, so heavy in places like Ephrata (four inches), that it turned midday into darkest night and blanketed everything in a choking, abrasive powder of cement-like consistency. More than 500 million tons had already dropped on parts of Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

St. Helens aerial view looking north. Mt. Rainier in the background. CREDIT: United States Geological Survey

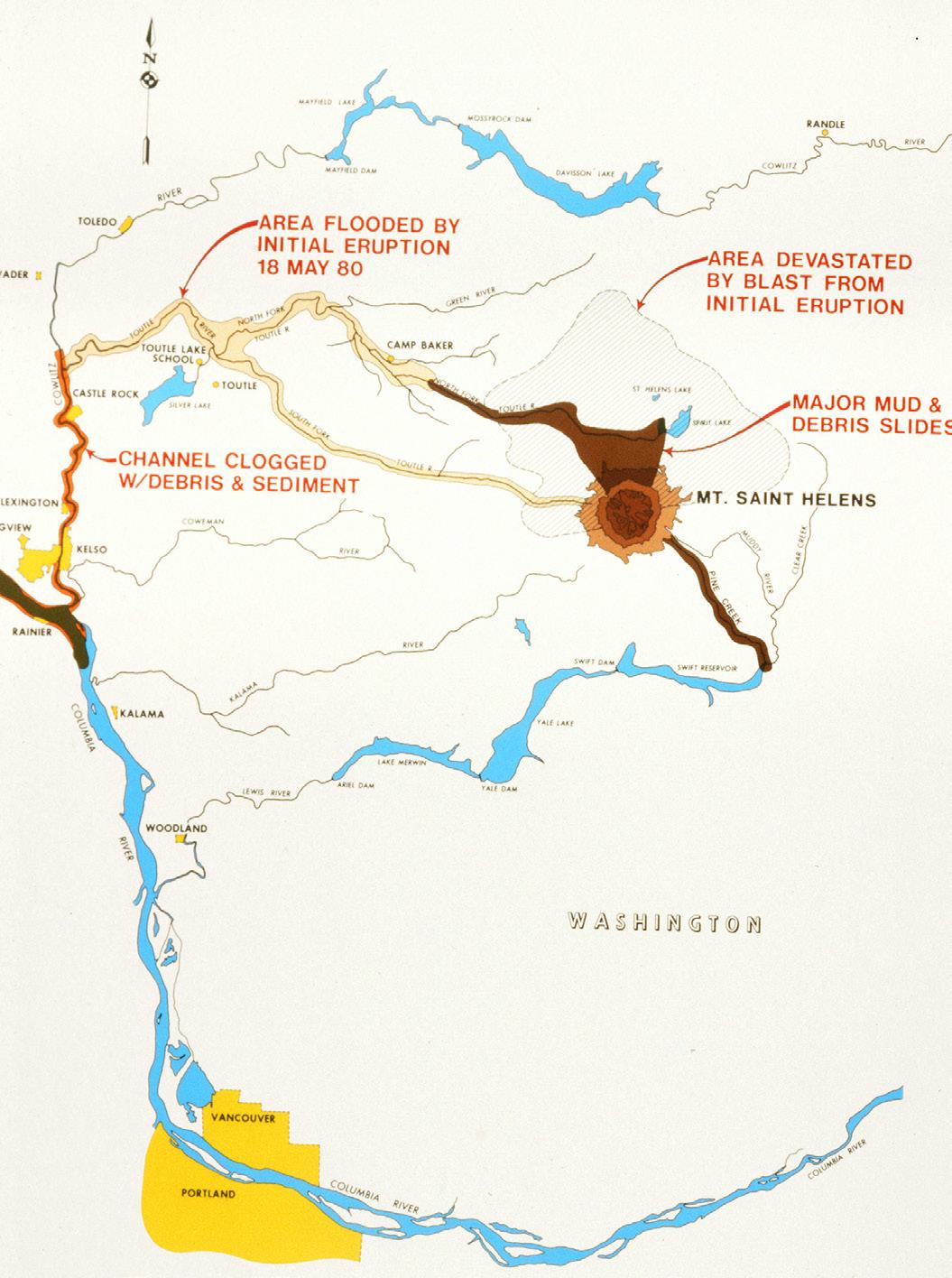

West of the mountain, all eyes were on the North and South Forks of the Toutle River, where initial volcanic lahars (hot mudflows) had filled miles of the watercourses with debris to depths of 600 feet. Melting snow had increased the normal volume of water, over and above the massive mudflows, leading to numerous instant lakes and ponds, any of which might drain suddenly without warning. The I-5 bridge over the Toutle, 60 miles north of Portland, stands immediately east of where the Toutle joins the Cowlitz.

Until we arrived at the bridge, we had no way of knowing whether we would be allowed to cross. We crawled forward slowly on queue, but probably within half an hour a state patrolman waved us through. We were home free. Well, almost.

Once in Seattle, some of the crew stayed in the Husky house. Some rejoined family. Everyone waited and watched the news. By Tuesday it was clear that I-90 would not reopen anytime soon. Early Wednesday, we clambered aboard our Greyhounds and rode back to Portland, then east to Walla-Walla. At the WallaWalla Greyhound terminal, drivers advised us that the route through Colfax was impassable and we would re-route through Lewiston. The southerly route was judged superior, but arrival in Pullman could not be guaranteed. This news so frustrated one weary oarsman that he punched the window next to him, damaging the glass. What happened to his hand is a mystery to the author. Fifteen hours after leaving Seattle, Cougar Crew had returned to home base.

Tina (Randall) Monsaas recalls: “By the time we arrived it was dusk or dark. Drop-off was far away from my dorm. Dust billowed whenever I stepped off the sidewalk. No one was outside. It was like the Twilight Zone.”Our long bewildering trip had ended. It was the week before finals.

David Johnston at USGS observation post Coldwater II, 1900 hours, May 17, 1980. Coldwater II was re-named “Johnston Ridge” in his honor. The US Forest Service Johnston Ridge Observatory is now the interpretive visitor center for St. Helens. CREDIT: Harry Glicken. Public domain. Mapping the damage. CREDIT: US Army Corps of Engineers

—Rich “Flip” Ray (’80)

EXTRA NOTE

Readers may be wondering: Did Flip take Geology 101 (“Rocks for Jocks”)? No, I didn’t. Maybe I should have. Many teammates helped me remember this story. Special thanks to Randall sisters Kathleen and Tina (now Monsaas) and Louise (Hill) Thomas. Thanks as well to Tom Anderson, Dave Arnold, Eve Boe, Lisa (Coble) Curtis, Gene Dowers, Dave Emigh, Doug Engle, Susan Ernsdorff, John Holtman, Mike Pabisz, Mark Petrie, Kari and Steve Ranten, Tim Richards and Ken & Marj Struckmeyer. If I have forgotten someone, please accept my apologies.