5 minute read

Yesteryear The Old Adobe: Coronado’s First Attempt at Historic Preservation

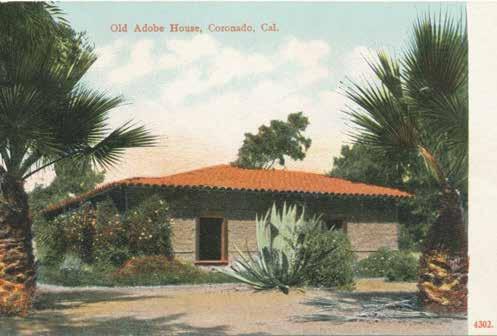

The Old Adobe: Coronado’s First Attempt at Historic Preservation

by Vickie Stone, CHA’s Curator of Collections

Advertisement

In 1887, the construction of the Hotel del Coronado was well underway. The Coronado Beach Company, in preparation for the hotel’s opening, was beginning to develop other attractions to entice guests to visit this budding resort town. Elisha Babcock, one of the founding partners of the Beach Company, was especially adamant about creating experiences that celebrated the romanticism of the West.

Inspired by the history of Spanish colonization, California’s missions, and indigenous design, Babcock commissioned the construction of an adobe building at the center of Coronado’s East Plaza, known today as Spreckels Park. Construction began in early 1887 and largely consisted of bricks made near Otay Mesa by Mexican laborers.

After Coronado incorporated, the City took over maintenance of the building from the Beach Company. However, Babcock remained devoted to his vision for the adobe building. He was able to source and obtain “time-marked” tiles from Mission Viejo and the mission at San Juan Capistrano to cover the roof of the building. In 1891, he presented the tiles to the city’s Board of Trustees as a gift to give the building “historic value” (San Diego Daily Bee March 26, 1891).

The small, unimposing building was intended to be a museum of “a collection of curiosities,” according to the earliest reports Children stand in front of the old adobe building. Date unknown. Coronado Historical Association Collection.

by the San Diego Daily Bee in May 1887. However, by the time the building was completed, there was no more mention of a museum. The building simply stood “as a relic of early times in Southern California” and was “being preserved as a curiosity” (San Diego Daily Bee June 2, 1887 and Coronado Mercury March 21, 1888).

Aside from simply standing, the building did function as a community space for a short time. One special event was when the building housed Charles R. Orcutt’s collection of cactus. The collection, claimed to be the second largest cactus collection in the United States with over 500 specimens, was gathered by the naturalist from across Southern California and Baja California. Orcutt was later a founding member of San Diego’s Natural History Museum.

By 1903, the “Old Adobe” was solidified as one of Coronado’s laid back attractions. As advertised in Tent City News, “Down on Orange avenue on either side of the car line are two exquisite little parks which are the most delightful resting places possible. In the centre of one is an old adobe, vine-covered and surrounded by trees, palms and foliage which cast the deepest shade.”

In later years, the building’s appeal faded and it was used as a tool shed and for a time, and in 1914, the building served as the location of the local dog pound. Maintenance declined and the building fell into disrepair.

In 1915, City Trustee Newton S. Gandy, a relative newcomer to Coronado at that

time, asked that the adobe building be removed, citing it as “a nuisance generally.” Trustee George Holmes, a longtime Coronado resident, went on the defense for the building saying that in its 25 years of existence it had been admired by thousands of people. (Coronado Journal January 30, 1915)

There was a small stirring from the community in opposition to demolishing the building. Not only was Geroge Holmes upset, but it seemed that other long time residents felt the same. The Coronado Journal argued, “When thousands of dollars are being spent all over the State to restore the Missions, so as to retain the early California atmosphere, it seems to us to be wrong to destroy the only relic of the early days we have” (Coronado Journal January 30, 1915).

It’s not clear how he became involved with the project, but master architect William Templeton Johnson took an interest in saving the building and agreed to make an estimate of the cost of restoring the building. His report to the Trustees was that it would cost $836 and an additional $700 to “really make use of the building as a shelter”.

Harrison Albright, another notable architect, took up the cause by writing an impassioned letter to the Board of Trustees. It read in part:

“Other towns in California are carefully preserving and even restoring such relics of a past civilization, and the great interest taken in such places by people from other lands as well as from our own State shows that there is good and ample reason for so doing. It therefore to me seems unfortunate that Coronado should wish to destroy the only relic of the sort now within its corporate limits, situated as it is on public property where its presence jeopardizes the financial interests of no individual. We should instead take steps not only to preserve this interesting bit of early California, but even to partially or wholly restore it to its original state, that the visitors to Coronado, coming from all the world, may find at least one relic of a past full of historic interest.”

Sadly, Albright’s letter arrived too late. The Trustees had already approved the building’s removal and it was demolished by the time his letter arrived. The roof tiles from the missions were saved for some time, and suggested to be repurposed for other city projects in the future, but current documentation does not cover their ultimate fate.

Trustee Holmes held a grudge about the demolishment of the old adobe building, as evidenced by his remarks at a Board of Trustees meeting a year later. When the Board was discussing possible locations for election poll stations, “Holmes suggested that if the old adobe in the park had not been destroyed it would have made a fine voting place, and everyone laughed, even Gandy joining in.” (Coronado Journal February 19, 1916)

Adobe building featured on a 1907 postcard. Courtesy of the Ann Price, Imperial Beach Historical Society.