23 minute read

Welcome, Dear Readers by Meredith

Welcome, Dear Readers

As I write these words, more than 20 years have passed since I came up with the crazy idea of putting together a magazine that focused solely on historical fiction. The concept for The Copperfield Review came by accident, as most good things tend to happen to me. I was writing my first historical novel and thought I would try to get the word out by publishing a few pieces as short stories in literary journals. Much to my surprise, I couldn ’t find one literary journal that published historical fiction. Around this time I was teaching creative writing classes at Learning Tree University in Southern California. As I read the LTU catalog I noticed a class about how to create an ezine, a fairly new concept in 2000. The class sounded interesting so I signed up. Before the six-week course was over, I knew I wanted to create an online journal of historical fiction. I even had a name—The Copperfield Review, yes, named for Dickens ' novel. I commissioned a website, I created the logo, a drawing of Dickens ' hand holding a quill, and I set about finding writers to contribute. I also landed interviews with two of my favorite historical novelists, John Jakes and Jean M. Auel. "Who is even going to read this?" I asked myself as I pieced the journal together. But Copperfield, which I refer to as the Little Journal That Could, had become important to me. I sensed that there were readers and writers who loved historical fiction as much as I do. I believed that there was a place in the literary world for The Copperfield Review, so I pressed on despite that nay-saying voice making noise in my head. I love that we ’ re featuring an interview with the beloved historical novelist Steven Pressfield in our inaugural edition of Copperfield Review Quarterly. Pressfield is also known for his books The War of Art and Turning Pro. Both books are essential reading for writers. In his books, and in his interview in CRQ with Brendan Carr, Pressfield talks about the concept of Resistance, a creative block that every artist has to deal with in one form or another. Whenever you feel as if you ’ re giving into fear-based decision-making, whenever you stop yourself from trying or creating something new, you ’ re struggling against Resistance. Man, have I struggled with Resistance over the years. In my initial conception of The Copperfield Review, I thought I would use the e-zine format until I could find a way to make bound copies. I had a lot of plans for Copperfield, and even as the journal gained in popularity (within a year we were receiving far more submissions than we could ever publish) I held back on growing it too much. I had excuses galore, some of which were legitimate, and some of which were pure Resistance. The years passed and The Copperfield Review continued to grow in popularity. The truth is, we have a strong reputation because of the writers we ’ ve been lucky enough to publish. Crazytalented authors and poets have sent their work our way, for which I’ll always be grateful. Even the works that we don ’t publish are special in their own ways, and it’ s a privilege to read them. Fast forward to 2019. I wanted to do some fun things in 2020 for Copperfield’ s 20th anniversary. And then. I don ’t need to explain what the pandemic did to all of our lives. We ’ re still coming to terms with what it meant and what it still means. Some of us were sick, some had friends and family who were sick, others lost jobs, and too many lost loved ones. Even though I' m writing about the pandemic in the past tense, COVID-19 is still very much here and more waves are rising every day. We have some soul searching to do as we make sense of this volatile disruption of what we knew to be true. While some artists were prolific in 2020, I know others, who, like me, spent weeks staring at the wall. It took a good few months of living through the pandemic, especially when we were in the strictest lockdowns, for me to find my creativity again. I also did a lot of thinking about my life and where I was putting my attention. What did I really want? I asked myself that question countless times throughout 2020 and into early 2021. Really, what did I want? The answer came back that first, I wanted to devote more time to my own writing. While I have had a wonderful career as a writer, I know there is more I can do. Perhaps I hadn

Advertisement

Second, I decided that 2021 would be the year that The Copperfield Review became the digital and print journal I always meant it to be. Yes, it would be a lot of work, and yes, I still felt Resistance, but I also had a sense that, you know what? It’ s time. Fortunately, I gained enough resilience over the years that I can now mostly fend off Resistance. I haven ’t eradicated it completely (no one can), but now I can lower the volume of the noise and be productive anyway. And in the 20 years since I began Copperfield, technology has evolved and it’ s easier now to create digital and print versions of journals and magazines. I’ m a big believer that everything happens in its own time. Even though this is what I wanted for Copperfield 20 years ago, it feels right that it’ s happening now. Now I’ m coming to the experience of creating a magazine with two decades of running a literary journal under my belt. Now I have a better sense of what I’ m doing. I still have a lot to learn, and I’ m always looking for ways to improve my writing, my editing, and myself, but I’ m excited about this new venture in a way I wouldn ’t have been even a year ago. Instead of shying away from challenges, I’ m learning to look them in the face, see them for what they are, and try new things anyway. I hope you ’ ve had similar discoveries that are pushing you in new, wonderful directions. Now that the inaugural edition of Copperfield Review Quarterly is ready for its close-up, I’ m spending some time this summer hanging out by the swimming pool, reading some good books, and writing the next draft of my latest historical novel. And then it’ s back to work getting the next edition of CRQ ready for its October release. I hope you enjoy this first edition of CRQ. We have the interview with Steven Pressfield that I mentioned, and we have a feature and a new poem from one of my favorite living poets, Ann Taylor, who has been a long-time contributor and friend of Copperfield. We also have a wonderful selection of short historical fiction and poetry for you. Whether you ’ re reading a digital or bound version of CRQ, I welcome you to this new incarnation of The Copperfield Review. What have you learned as a result of the pandemic? Has Resistance been a factor for you? Let me know your thoughts at copperfieldreview@gmail.com. We can all learn from each other. I wish everyone some fun in the sun this summer. I’ll see you in October for CRQ’ s Autumn 2021 edition. Meredith

Meredith Allard Executive Editor, Copperfield Review Quarterly

Available now at https://copperfieldreviewcourses.teachable.com/p/an-introduction-to-writing-historical-fiction

A N I N T E R V I E W

W I T H S T E V E N P R E S S F I E L D

By Brendan Carr

Steven Pressfield is the author of Gates of Fire, a historical novel that has sold more than a million copies. Pressfield is also known for his much-loved books for creatives, The War of Art and Turning Pro. You can learn more at StevenPressfield.com.

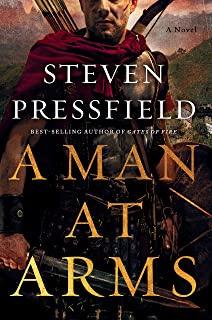

In this interview, Brendan Carr and Steven Pressfield discuss Pressfield' s newest novel, A Man at Arms, along with Pressfield' s writing process and what it means to overcome Resistance, that little voice that tells us to resist our creativity.

Brendan Carr: Telamon of Arcadia is a mercenary in your newest book, A Man at Arms. What are you saying about warriors by making your archetypal warrior into a mercenary?

Steven Pressfield: What I was hoping to do as far as characterizing Telamon was to present him as a guy who exhausted the warrior archetype. He fought under flags that he believed in, fought for commanders he believed in, and had that come to naught. He committed crimes and he committed honorable acts. But he was still a warrior, he was not going to leave that aspect of it and that brought him to become a soldier for hire, a man at arms. He was in it for the fight alone, like a samurai when they no longer fought for a particular noble house but were just freelance guys who were cast out on the road. In other words, it’ s a dark place for him to be. I’ m not holding that up as an ideal. In my mind, it’ s the stage that a warrior or a hero is in when he ’ s trying to find his way and hasn ’t found it yet, a kind of a lost place. That was why I made him a mercenary.

B.C.: You ’ ve been wanting to write a book about Telamon for a while. What is it that draws you to him?

Pressfield's latest historical novel

STEVENPRESSFIELD

CONTINUED

S.P.: That’ s a great question! I feel like he ’ s a bit of an alter ego for me as a writer. The way he views himself as a soldier, he ’ s in it for the fight alone. He ’ s not in it for the money although he ’ s a mercenary. We don ’t know what he does with his money, but he doesn ’t have anything except the clothes on his back. It’ s not like he ’ s getting rich; the money is really just an excuse for him. It’ s a way to keep a distance between himself and his commander ’ s ambition. He says, “I’ m just doing it for the money, ” but he ’ s in it for the fight alone. I’ m kind of in writing for the work alone. So, I think that’ s one of the reasons why he appeals to me. He also has a kind of a dark view of life and I do too.

B.C.: And lost characters are often depicted alongside a redemptive character. How did you develop the character of the young girl, Ruth, in your story?

S.P.: I very much did that on purpose with the idea of juxtaposing archetypal characters on my mind. I knew for years that I wanted to do a book that was only about Telamon because I was curious about where he would go after appearing in two other books of mine. He was in The Virtues of War and Tides of War and I was fascinated by his odyssey, but I couldn ’t find a story for years.

I would take a shot at an outline asking,

“What if I set him in Britain in the year 22 or something?” When I finally thought of this character of the young girl, it made a great dynamic of different archetypes. An innocent girl, that’ s sort of the virgin archetype, and then this warrior archetype together created a lot of interesting tension and chances for growth on both sides as they interact with each other.

B.C.: What draws you to Carl Jung ’ s archetypes? And how can writers use them?

S.P.: Let’ s talk about the archetypes for a second. The archetypes of the collective unconscious are these super personalities that we ’ re born with and that are Types, capital T, like the Wise Man, the Warrior, the Virgin, the Divine Child, like Jesus or Krishna.

There are many archetypes and I believe that we don ’t realize it but we ’ re being powered by them.

Speaking of the Warrior archetype, when a young man and I think a young woman, too, hits the age of 12, 13, 14 they can feel that sort of thing. They ’ re not aware of it, but a young guy wants to try out for the football team, wants to drive fast, wants to hang out with his homies. We think we ’ re choosing that but we ’ re not, we ’ re being driven by archetypes.

Back to writing, a really interesting way to power a scene is to have a clash of archetypes. I’ ve been watching Game of Thrones and last night one of the scenes showed the young girl Arya Stark serving as a cupbearer to her worst enemy, Lord Tywin Lannister. The scene between the two of them is a great scene because of the two archetypes.

A better thing might be Obi-Wan Kenobi and Luke Skywalker. A young Warrior archetype and the Sage archetype, and there ’ s a lot of great energy when you do that in a scene. If you look at practically any great movie or book, the characters are almost always archetypes. Think about the major characters of The Godfather and their enemies, the five families, they ’ re all archetypes. That gives the story its power.

I’ m also a big believer in just reading great stuff and watching great movies if you look at them through the lens of the archetypes to educate yourself.

For example, with To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch is sort of the archetype of the Knight, the upright and honorable man. The other characters are archetypes too. Try to educate yourself that way. Of course, you want to create nuanced real characters, but I do think that what gives characters power is that sort of archetypal energy.

B.C.: After writing several non-fiction books, you ’ re returning to the craft of writing historical fiction. How do you make history feel so real in your books?

S.P.: It’ s the imagination. It’ s trying to imagine yourself back in that world, whatever world it may be. Arthur Golden, a Jewish male writer, wrote this wonderful book Memoirs of a Geisha. It was a bestseller. Basically, he beamed himself in imagination back into the mind of a Japanese geisha female courtesan in the 1930s and when you read it you completely believe everything.

So, I think he did a lot of research, he found out all the details of what the true world was like, but then he just used his imagination. In a way, that’ s a quality of any storyteller. So, I think he did a lot of research, he found out all the details of what the true world was

STEVENPRESSFIELD

CONTINUED

like, but then he just used his imagination. In a way, that’ s a quality of any storyteller. When we were kids, if we got caught by our mom stealing something or caught by the principal, we would stand in front of the principal and just lie like a son of a bitch, right? So, it’ s that quality of imagination, which is a lot of the fun of it. I wish I could get in a time machine and go back to ancient Athens and see what it was like to walk out in the morning and talk to people, but I can ’t. So, I do it in my imagination and try to write with that.

B.C.: How do you choose what projects to pursue?

S.P.: I’ m a believer in the Muse. I believe that it inspires from some other dimension of reality and I never really know what the next project is going to be. I tune into the cosmic radio station and receive my assignment. I’ m always looking for something that’ s going to make me stretch a little bit, something I haven ’t done before. I certainly don ’t want to repeat myself, but usually when an idea comes, it’ s a surprise.

That’ s why I’ ve been bouncing back and forth between things that are about the creative process like The War of Art and novels like A Man at Arms. I never know what’ s coming next, but I know when I look back over the progression it all makes sense in some crazy way. Look at the whole through-line in Bruce Springsteen ’ s albums and there ’ s definitely an evolution. It’ s the same theme he ’ s obviously obsessed with. He ’ s evolving and treating them in deeper and more nuanced ways.

B.C.: When you are writing, what does that process look like?

S.P.: I have two ways of approaching it. One is a very blue-collar way, I have a saying, “Put your ass where your heart wants to be, ” which means you sit at the keyboard and just show up every day.

The other half is that I’ m definitely a believer in the Muse and that you get inspiration and that when you ’ re working well you don ’t even know what you ’ re doing. You go into another state of mind and you ’ re channeling stuff. What I’ m trying to do as a writer when I’ m actually sitting down at the keys is to get out of my own way, get my ego out of it completely, and even get my identity out of it. I’ m in a state of imagination and in a very real sense, I think you start to see the story that you ’ re telling and you ’ re guided by your own instincts. From my experience in the Marine Corps, I have a sense of what men are like in the field, what the humor is like and how everything goes wrong. It’ s kind of a mysterious thing, getting into a state where you partly surrender your own control over to what’ s going to come out on the page, but at the same time you ’ re bouncing between your right brain and left brain. You ’ re trying to control it a little and if the scene starts going in the wrong direction you try to rein it back a little bit and remember where you want it to go. I know it’ s kind of a vague answer.

B.C.: Interpreting the Muse is obviously a big part of your process. How do you discern what’ s coming to you?

S.P.: I always keep a file I call “ new ideas. ” Let’ s say I’ m working on A Man at Arms, I’ m constantly looking out in my head for what’ s next. I’ll have a bunch of candidates in my “ new ideas ” file, maybe a movie that I want to do, or a small book I want to try, or a video series, or a collaboration. I’ll put all those things down and check in with them from time to time and ask myself, “Does this make sense? Could I do two years of my life on this particular project?” At times I’ ve found that at first an idea leaves me cold, but sometimes it takes quite a while for things to sink in.

Actually, the next project that I’ m going to do is an autobiographical project. But here ’ s the interesting thing, my girlfriend Diana urged me to do this and I’ ve been resisting it for months.

But little by little I recognized that as my own Resistance with a capital R, meaning that it’ s a good idea and I’ m afraid of it. I’ m putting up this selfsabotage in my mind. It took me six months, but I finally bought into the idea and I am going to do it. This might be a bomb. I might spend two or three years and it might just totally lay there, but I’ m at the stage where I’ m willing to take that chance.

t’ s a challenge and I want to give it a shot. I ask myself,

“Do I really want to work on this thing for another day?” I recognize my own Resistance there because I’ ve seen it enough in my 50 years in this racket. So, I say to myself, “Okay, let me push through it. "

STEVENPRESSFIELD

CONTINUED

Another big thing for me is dreams. I’ m a big believer in paying attention to your dreams because it’ s coming from your unconscious. It’ s coming from that deep source that knows you better than you know yourself. Paying attention to your dreams is an amazing practice that people don ’t necessarily pick up very often. I’ m a child of the 60s, and certainly a number of different friends have sat me down and given me the talk about paying attention to your dreams. I’ ve tried it enough in my own life and it’ s worked a bunch of times. Dreams have steadied me on a course, but when I was doubtful a dream would tell me to keep going too. It’ s worked for me.

B.C.: What advice do you have for writers contemplating big projects, such as a work of historical fiction?

S.P.: In my book The War of Art I talk about this concept of Resistance with a capital R. Resistance in my definition is that negative voice we hear in our heads that tells us we shouldn ’t do this project. As I plan my next book, I’ m getting this voice in my head saying,

“This is a dumb idea. Nobody ’ s gonna care about this. It’ s been done a million times. You ’ re going to look like an idiot. ” That’ s the voice of Resistance and one of the laws of Resistance that I have found over the years is that the more Resistance we feel to a project the more important that project is to the evolution of our soul.

So, big Resistance equals big idea. In other words, if you ’ re feeling a lot of Resistance to something, that’ s a good sign.

The analogy I make is to think of a dream that we have for a project as a tree in the middle of a meadow on a sunny day. As soon as that tree goes up the tree is going to cast a shadow. That shadow is Resistance, but there would be no shadow if there wasn ’t a tree first. So, Resistance always comes second. When we ’ re feeling big Resistance it’ s because there ’ s a big dream. In the project I’ m working on I’ m using that to encourage myself, because I say, “Oh, if I’ m feeling that much Resistance this project must be important to me. ” There ’ s really no substitute in this case for willpower and whatever it takes for each of us to find his or her way to work through something like that. Some of us hit it head-on, some use kind of a jiu-jitsu method, but somehow, we ’ ve got to find a way to get through that Resistance and keep working.

So, if you ’ re feeling big Resistance, that’ s a good sign. If you ’ re very much afraid of something, that’ s a good sign.

Brendan Carr is a podcast host, writer, and military veteran. He holds a Master ’ s degree from Columbia University. To see more interviews, check out http://youtube.com/BrendanCarrOfficial.

WHATISHISTORICAL FICTION,ANYWAY?

By Meredith Allard

What is historical fiction? On the surface, it seems like an easy question to answer. According to masterclass.com, "Historical novels capture the details of the time period as accurately as possible for authenticity, including social norms, manners, customs, and traditions. Many novels in this genre tell fictional stories that involve actual historical figures or historical events. "

While the definition from Master Class gives us the nuts and bolts of what we mean when we discuss historical fiction, the truth is there is no one answer to the question "What is historical fiction?"

Everyone who loves to read or write historical fiction has their own thoughts and opinions about how they define the genre, which is a very good thing for those of us who love to read and write historical fiction.

There are a few basic guidelines when considering whether or not stories fall into the historical fiction genre. The story should take place in a clearly defined historical era. Part of the joy of reading historical fiction is learning about the details such as events, places, and dress that could have only come from that era.

Through fictional snapshots, we can connect to a time that we couldn 't experience any other way. We can be time travelers with one foot in the present and another in the past while we learn about people ’ s day-to-day lives. As far as I' m concerned, historical fiction is the best of all worlds. Maybe you think historical fiction is the best of all worlds too.

For CRQ' s inaugural edition we asked readers and contributors for their answers to the question, "What is historical fiction?" We received some great responses. Here ' s what they said.

Jennifer Smythe: Historical fiction means learning about our place in today ' s world while seeing how things have changed over time.

Lynda Gosselin: Historical fiction is emotion. I can learn about facts in history books but I can only learn about how people felt through fiction.

Billie P.: Historical fiction is engrossing fiction. I can learn and visit another world at the same time. Ann Taylor: The first necessity, I think, for historical fiction or poetry is genuine curiosity about the historical record, some interest in what has been said and in what else may be said, and a desire to say it in an engaging and thoughtful way. All good literature is an expression of some kind of hope, the desire to say something worthwhile and to be read. As Seamus Heaney said in his The Cure at Troy, “History says / Don ’t hope on this side of the grave / But then, once in a lifetime / The longedfor tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme. ” Hope and history can rhyme too in successful historical literature.

Martha Wilcox: Historical fiction is pure escape for me. When I' ve had a hard day or I need to kick back I reach for a historical novel.

Tom B.: Historical fiction is life as it was and as it is. I think the reason I like historical fiction is because I like to learn new things.

Rachel Smith: Historical fiction can give voice to those who were marginalized at the time– the people whose stories didn ’t make it into the history books. Not only that, but it can expose patterns and parallels between then and now, illuminating the ways in which the past has shaped the present and reminding us of the price of not learning from our mistakes.

Jane Wilder: Historical fiction is hard to define for me because it' s so many different things. Mainly, historical fiction is a great story wrapped up in fascinating facts about the past.

Mary Ressenor: Since I read and write historical fiction exclusively, I would say that I define historical fiction as my life ' s blood. It satisfies my curiosity about how people survived in difficult circumstances and retained their humanity. We still need that lesson today.

Nick Link: Historical fiction is a dip into life in the past.

Historical fiction means different things to different people. There ' s something for everyone in this beloved genre, which is why readers and writers are drawn to historical fiction again and again.