7 minute read

Taki Kitamura

from Discover 13.1

In a Constant State of Grace

Written by Grace Talice Lee | Tattoo photography by John Agcaoili | Portrait photography by Daniel Garcia

Advertisement

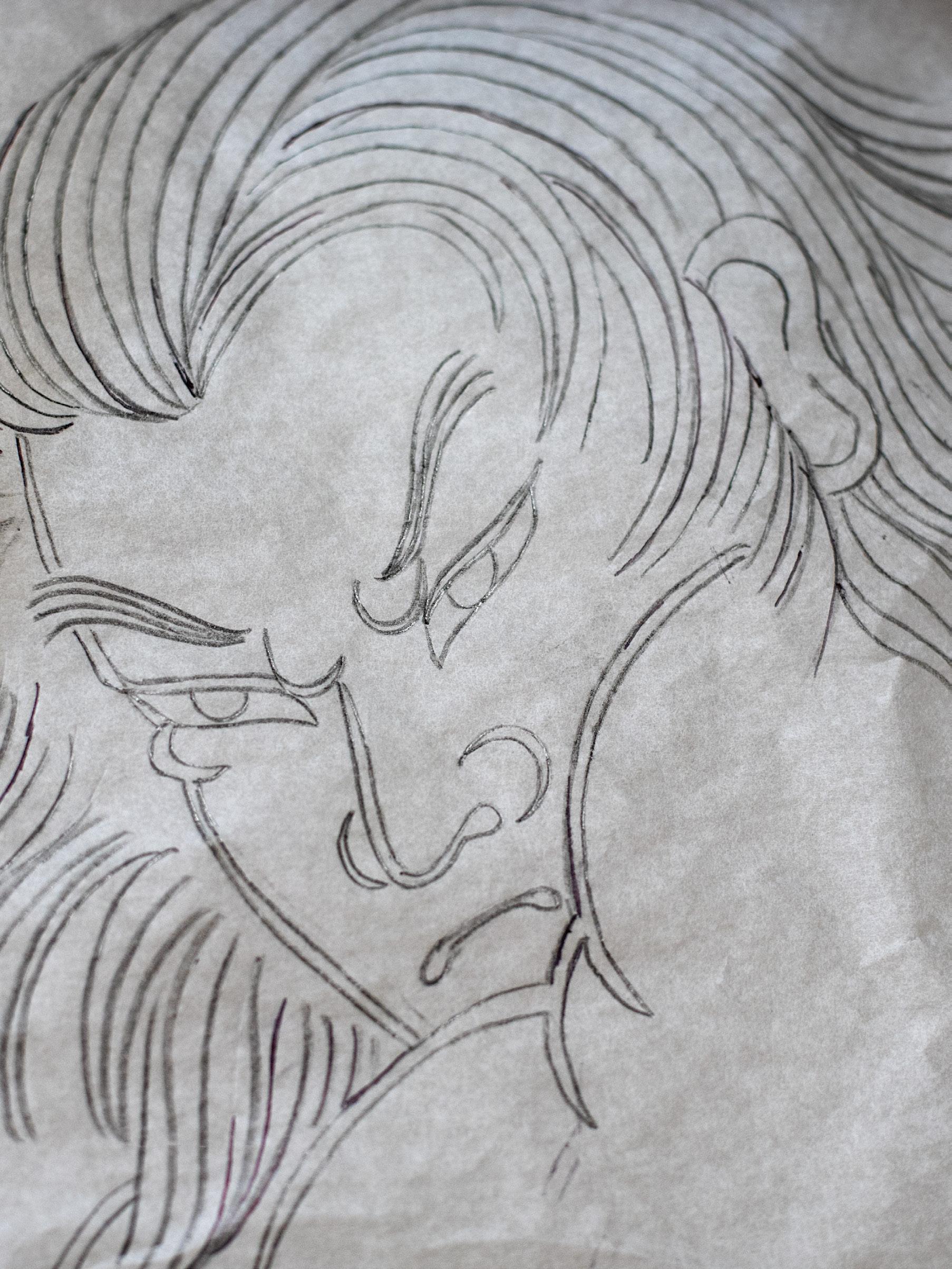

At first glance, Taki Kitamura might be exactly who you’d expect to own State of Grace, one of the shops that brought traditional Japanese tattooing to this side of the Pacific. He apprenticed for a decade with Horiyoshi III, the living legend of the style. Taki has adored the art form since childhood, when he drew back pieces on his friends with thick felt pens. And of course, he shows a clear love for his craft, as he is covered head to toe in several layers of tattoos. But if all you knew was Taki’s familial background, you would never guess his profession. Both of his parents served as pinnacles of social acceptability. His mother operated a ballet supply store and bussed the kids between Boy Scout meetings and youth symphony rehearsals. His father was a tenured professor of civil engineering who earned high honors from Kyoto’s mayor. And—having grown up in Japan where only Yakuza criminals got tattoos—neither of them would’ve ever, ever condoned the art form as a career for their son. Yet it was exactly that illicitness that Taki found so enticing. As a teenager, he got sick of finishing his parents’ extra math drills while all his friends went swimming and skateboarding instead. So, he rebelled. He shaved off half his hair, dyed his mohawk pink, and got his very first tattoo on the side of his head—a jagged design that he doodled during class. He was underaged, and he prayed the whole time that he wouldn’t get carded. Taki’s rebellion continued until the end of high school, when he lobbied to take a break before college. But his father flat-out refused, insisting that one gap year could too easily turn into two or three or more. So, the next fall, Taki enrolled in the University of California Santa Cruz, where he majored in community studies, which examines cultural identity with a heavy emphasis on field research. This taught him to commune with people unlike himself; to observe with the humility of a student and the criticality of a scholar; to learn from others while respecting their ideas, hopes, and histories, tools that would serve him well for the rest of his life. After receiving his bachelor’s degree, Taki moved to San Jose and found retail jobs selling car parts and working at a supermarket gift shop. But his love for tattoos never waned, and he often got fresh ink from Paco Excel at Newskool Studios. On one of those

visits, Taki let slip that he might be interested in pursuing the art form more seriously. “It was just one of those things where I was like, ‘Man, I want to learn how to tattoo!’ ” said Taki. “And I kind of just said it like, whatever, but [Paco] went ‘Yeah? You draw, huh? Bring in some of your drawings!’ And he agreed to teach me.” For the next few months at Newskool, Taki swept the floors, cleaned the bathrooms, and talked with customers. Most importantly, he had to draw, draw, draw. “One of the things Paco said was, ‘Before you can even touch the machine, you need to make ten sheets of flash designs,’” said Taki. “Then after about nine months of doing that, I was kind of let loose.” Soon, business picked up. Within a year, he even saved enough money to make something of a pilgrimage—to visit Yokohama and spend 10 days getting a tattoo from the master of traditional Japanese style, Horiyoshi III. Taki would be the second foreigner ever to receive a back piece from this titan. “For me,” he said, “it was like meeting God.” When the day arrived to meet his hero, Taki came fully prepared and bearing gifts. He gave a bottle of whiskey to Horiyoshi III and a Tiffany necklace to his spouse. As Taki said, “I feel like my parents, one of the ways that they raised me was manners. In the Japanese tradition, when you visit somebody, you bring a gift. And I’m not stupid—I’m not going to forget the wife.” Still, it was somewhat of a surprise when—after their second day of tattooing—Taki was invited to dinner with Horiyoshi III. And then welcomed to visit the studio early and just hang out. “So I get there the next day,” said Taki, “and I drew my ass off. Immediately I just took his drawings and redrew them in my sketchbooks, because in Japan it’s a very big thing where in the beginning, you copy your master, you copy the classics. And then at some point he says, ‘Hey, can you help me with these?’ and he hands me a stack of letters. So I spent all day answering fan mail.” Thus began a decade-long apprenticeship, with a few in-person visits a year and a continuous correspondence via fax. Taki received the training to uphold Horiyoshi III’s legacy—and in return, the disciple would bring this practice to the Americas. “When there’s stuff like this master-apprentice kind of thing, the apprentice is looking to learn something—but how useful are you to the master?” said Taki. In his case, it seemed like the teacher and student were a destined match. “My master wanted to go global, but he didn’t know how. And then, I came through the door.” A scant four years into his career, Horiyoshi III pushed Taki to start his own tattoo shop—State of Grace. “Oh man,” said Taki. “I’ll be honest; I think opening State of Grace was really challenging because at the time, I just had no idea what I was doing. I just knew I had to open the shop. We didn’t really think about it. We just went and did it.” In the 18 years since its inception, State of Grace has become

-Taki Kitamura

a true reflection of Taki’s values. The crew is small and familial, with seven artists on staff, including some who earned green cards based on their exceptional abilities. The space is minimal and clean, with lots of blonde wood and natural light—intentionally reminiscent of Shinto shrines and temples. The location is both accessible and just obscure enough, nestled amidst the small businesses of San Jose’s Japantown, atop a flight of stairs that almost shroud the shop in secrecy. “It’s amazing—those stairs will just cut so many people,” said Taki, with a chuckle. “We don’t have sale signs, we don’t have Groupons, we don’t do Friday the 13th promotions. We only want to work with serious people. If you want what we put out, it’s the friendliest place you can be in.” But if you really want to know what this shop is about, look no further than the richness in its name. “I think ‘State of Grace’ is what we are all searching for,” said Taki. “We all need to feel that balance, fulfillment, peace—whatever you want to call it.” It’s about straddling two seemingly contradictory sides, and bearing that tension with thoughtfulness, dignity, and respect. For Taki, it’s about being Japanese enough to receive his master’s teachings, yet American enough to start an enterprise in the West; being grateful to his parents for his strong work ethic, yet rebellious enough to follow a controversial path; being hungry for the next challenge, yet finding ease in exactly where he is—most likely in his second-floor shop, crouched beside a client, working on his next tattoo. C

stateofgracetattoo.com

stateofgracetattoo.com | monmoncats.com | 221 Jackson Street San Jose, 95112 | Instagram: stateofgracetaki & stateofgracetattoo