9 minute read

COVER STORY “ON PLACE & NON-PLACE” BY JON W. SPARKS

COVER STORY BY JON W. SPARKS

+ON PLACE NON-PLACE

Nelson Gutierrez, the Colombia-born artist behind the 2021 Projects gallery on Main Street, discusses fi nding inspiration in his homeland and history, and making a space for other artists to grow.

June 3-9, 2021

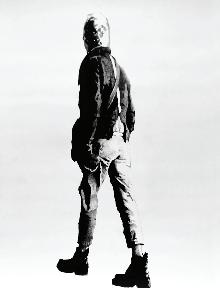

Artist Nelson Gutierrez

was born in Colombia and worked in various places around the world and in the United States before coming to Memphis six years ago. But you’ll be hard-pressed to nd anyone as devoted to local artists and art.

Gutierrez has an exhibition opening this weekend at 2021 Projects, a gallery at 55 South Main Street. at space is not the usual art venue, however, and that’s due to the artist working with the Downtown Memphis Commission (DMC) and numerous other artists in town to make it an attraction on several levels. at otherwise vacant space is part of the Open on Main retail initiative, a project that goes to the heart of the DMC’s mission to boost the economic presence of Downtown. ere are, as any who stroll along Main Street will attest, plenty of empty storefronts. Open on Main makes it possible for entrepreneurs, artists, and small business owners to take a low-risk chance on testing their concepts Downtown in some of these storefronts.

Open on Main

Brett Roler, vice president of planning for the DMC, says, “Blight and vacancy drag down property values, curtail a vibrant street life, and make it harder for our existing businesses to thrive.” It is clearly better to have open doors and engaged pedestrians. e program has helped more than 30 store operators test the retail market

Downtown, with more than 80 percent participation by minority/ women-owned business enterprises. Open on Main typically provides rent-free opportunities for tenants to have their pop-up businesses on

Main Street. e arrangement is usually for a month, but Gutierrez was able to secure a six-month plan since he was having rotating exhibitions of about a month each. His stewardship began in January and has gone well enough that the DMC has

PHOTO BY JON W. SPARKS Nelson Gutierrez’s art explores human identity, experience, and history.

agreed to let him continue using the space through December.

“What they’re doing is letting entrepreneurs use the empty spaces temporarily in order to test businesses,” Gutierrez says. “It’s not speci cally for art, but as that’s my eld, I said that that would be a good thing to do.”

He was talking with the DMC last October when so much was still closed to public activity, but they realized it was the time to start looking at ways to reactivate the art scene. “I knew there were going to be a lot of obstacles and limitations due to the pandemic, but we had the tools to do a lot of things virtually. It wasn’t just the exhibitions or the physical space, but also the social media that we would promote, and the interviews we’d do, and promoting the website.”

Gutierrez got together with artist Carl Moore and discussed who could be part of 2021 Projects. “We wanted to help the artists that are not represented by a commercial gallery, so that was our main criterion,” Gutierrez said. “Carl has been here for a very long time, so he knows more people than I do a er only six years that I’ve been in the city. We made a list of people that would be able to participate. Another criterion was the quality of the work, so those people had more need to nd spaces to execute their work or to reach the public.”

Artists who have exhibited so far are Andrea Morales and Khara Woods (February-March), Maritza Dávila and Carl Moore (MarchApril), and Johana Moscoso and Scott Carter (May). Gutierrez’s retrospective show runs from Friday, June 4th, through Friday, June 25th.

Portrait of the Artist

Gutierrez’s work is very much grounded in his experiences in Colombia, which have been, he says, in a type of civil asymmetrical war among the Colombian government, le wing communist guerrillas, right-wing paramilitary groups, and the drug cartels.

“It’s a really complex con ict,” Gutierrez says. “And I grew up in the middle of that. e government was ghting to provide order and stability. e guerrillas claimed to be ghting to provide social justice. e paramilitary groups were reacting to threats by guerrilla movements and to protect private interests. e drug cartels were ghting to protect their own businesses. And basically the people that most su ered were the civilians at large.”

He says most ghting was happening in remote rural areas in mountains and jungles. “ ere were several cases of terrorist attacks in big cities, which increased in the mid-’80s to the early ’90s. I was a ected directly by that violence. Everybody in Colombia knows someone that at some point was kidnapped. Everybody in Colombia knows someone that at some point was badly hurt or killed by these types of situations. So that was our reality.”

In the late 1990s, Gutierrez le his homeland and went to England to study for his master’s degree. It was transformative. “When I started seeing the whole thing from outside, everything changed because when I was living in Colombia, I was used to it,” he says. “ at was what we were seeing every single day in the news. We didn’t even have a sense of shock anymore. at’s not normal.”

He started to do some work on the subject of kidnapping. “ ere were about 1,500 people kidnapped,” he says, “so the work is about that and the spaces where people are kidnapped and how families su er — all the psychological impacts of these particular crimes in a society.” And there were the land mines. Gutierrez says more than 11,000 people were killed or wounded by land mines in Colombia. While in England, he did an installation for UNICEF and the Colombian

Embassy regarding that. Despite a 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, the United States, along with China, India, Pakistan, and Russia, have not signed the treaty. Colombia, however, did sign it.

The Road to Memphis

A er his master’s degree, Gutierrez went back to Colombia to teach for a couple of years, and he met his wife. ey moved to Miami where he worked for an educational foundation. A er four years there, he went to Washington, D.C., for eight years, continuing to do his art and to teach. His wife worked with nonpro ts, including United Way International, until she received an o er from the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), the fundraising organization for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

And that’s how they came to Memphis.

He got an o er to work with ArtsMemphis as an artist advisory council member in 2016. “I was helping

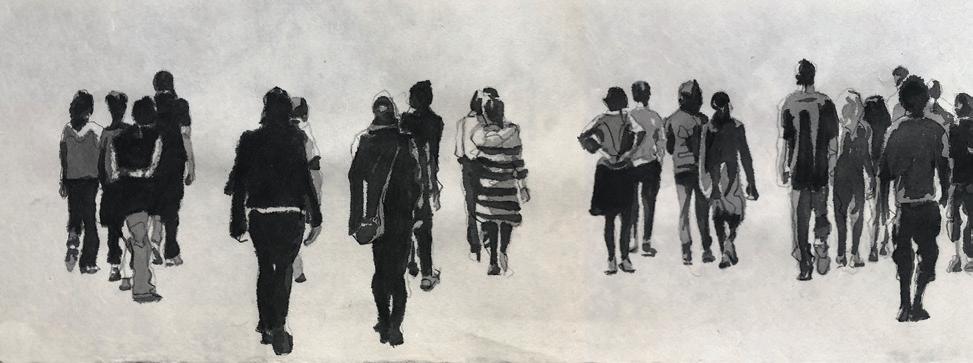

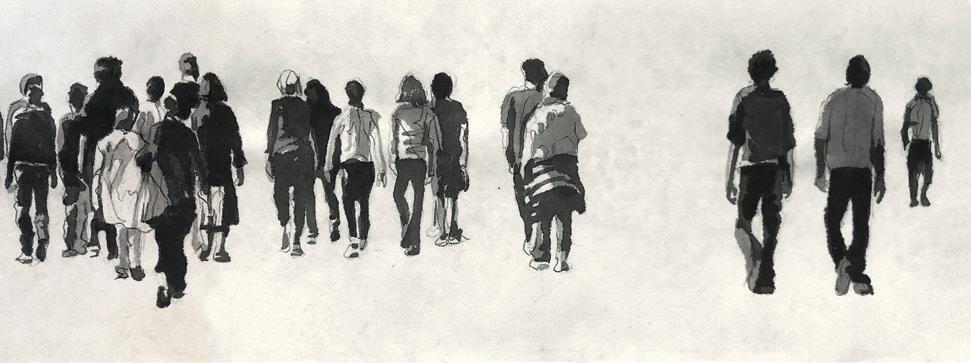

(above) e Walk, ink and pencil on paper, 54 x 8 inches, 2021; (le ) Norma Constanza Esguerra, plexiglass and MDF, 25 inches diameter, 2019

memphisflyer.com

COVER STORY

Youth, acrylic on paper, 25 x 25 inches, 2021

to understand better the situation of diversity in the city and in the county and how we could impact, in a more balanced way, the artists in the city based on that,” he says. In those years, he met artists and did work with the UrbanArt Commission. One of those artists he met was Carl Moore, who told Gutierrez about the program.

Being able to secure 2021 Projects for an additional six months was a de nite win for Gutierrez. “When we rst made the list of artists, the list was really extensive,” he says. “It’s not just the people that we’re showing now — there are a lot more people that we would like to support and show their work.”

Sorting Through His Passions

As for his own work, he continues to address the issues in his home country. “Having lived that con ict from inside and then seeing it from outside and seeing it now a er 20 years, how do I feel about that?” he wonders. “I don’t feel like I’m a hundred percent Colombian anymore — it’s not that I’m not

The smart money is on four in a row.

Powered by

June 3-9, 2021 January 28-February 3, 2021 After three straight Best of Memphis wins, the odds of Southland winning Best Local Casino again are pretty good. So pick a winner and nominate us again for 2021.

Must be 21+. Play responsibly; for help quitting call 800-522-4700. Then join us for the 10 Minute Cash Dash, 7-9 PM every Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday in June, where you can win $500 in cash.

CRAPS | BLACK JACK | ROULETTE | SLOTS | SPORTSBOOK

Colombian, but I don’t feel as I used to feel before. ings have changed, and I have changed. I’m trying to understand that and understand the history of the country and understand that as an outsider-insider. I don’t know — is that like a weird situation of non-place?” ese are the musings of an artist sorting through his passions. But it is what artists do, and Gutierrez is not idling. “Some of the work that I’m doing now, some of the drawings that I’ve been working on are based on photographs from the 1940s and 1950s,” he says.

Some of those photographs were taken on April 9, 1948. A political assassination that day sparked violent riots that came to be known as “El Bogotazo.” It changed history.

“ at started the violence that we’re living in now,” Gutierrez says. “So that’s what I am working on now. And how am I seeing that from the outside 75 years later? Even a er 75 years, you see repercussions of those acts.”

Whatever questions he still has, Gutierrez knows this about his art: “ e intention of the work is to point to this reality and to engage people in a critical debate around it changing in the public their habitual way of looking and thinking, in an e ort to create empathy again.”

Another view comes from Marina Pacini, who was chief curator at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art from 2001 to 2019. Speaking of a recent series, she says, “Like his earlier works, the images are a graphic exploration of human interconnections, and they emphatically demand close attention from viewers, who are rewarded for their e ort. With a simplicity of means, Gutierrez packs both a literal and a metaphorical punch.”