16 minute read

PAGES

Sheree Renée Thomas

A conversation with the Memphis author, poet, and editor. BY JESSE DAVIS

This spring, Sheree Renée Thomas released Nine Bar Blues, a new collection of short stories, via Jack White’s Nashville-based ird Man Books, the literary arm of the Raconteurs and the White Stripes rocker’s ird Man Records label. Just a month or so after the release of Nine Bar Blues came the publication of e Big Book of Modern Fantasy from bigwig sci-fi editors Jeff and Ann VanderMeer. e collection includes a short story by omas. She is the author of Shotgun Lullabies: Poems & Stories and the editor of the critically acclaimed collections Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones. omas was also a recipient of a 2017 Artist Fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission.

ME AND MY MUSIC

Music is central to NINE BA R BLUE S. It informs the title, the prose in its lyricism, and it acts as a recurring motif that ties the collection together. e pages practically snap, crackle, and pop — like old deep-cuts vinyl on a turntable — with the sounds of the South, from country to blues to gospel to funk. And it’s in the author’s embrace of multiple genres that she stands out as a keen observer of the multihued mosaic that makes up Memphis’ culture.

“I didn’t set out initially to write a book where each story has some exploration of a genre, but I realized that was what I was doing. And for me music is such a big part of my everyday world. I was born into a family that truly, truly loves music,” omas says. “I think my fi rst memory is probably hearing if not Led Zeppelin, then hearing Parliament Funk in the house.”

About “Head Static,” one of the Nine Bar Blues’ stories in which the musical motif is most readily apparent, omas says, “I was thinking about what it might be like if your very existence depended on the ability to experience new music. … at constant innovation that humans have in expressing themselves through rhythm and tone.” Laughing, she describes fi nding a world-saving song like some hidden treasure out of Raiders of the Lost Ark, adding, “I also wanted to play on the quest story.”

“Claire had spent decades foraging through black vinyl, seeking black gold, the sound, the taste of freedom,” omas writes in “Head Static.” For Claire, the story’s protagonist, music is a sword and a shield, a way to connect and a path to forgetting. She and Animus are immortal alien music lovers on a quest to fi nd e Great Going Song, “the one that captured the true spirit of a world, its story, its many stories.” ey work as DJs, searching for songs to sample, and driving through deserts and rain, in search of underwater pyramids and ancient melodies of the future.

WRITING ON THE BORDERS OF THE NEW WEIRD SOUTH

The eclecticism of NINE BAR BLUES makes it refreshing, especially when compared with national depictions of the South. (Remember that ridiculous and short-lived Memphis Beat show where Jason Lee played a cop whose side hustle was as an Elvis impersonator? Yeah.) omas’ genius is simply in tapping into the already existing strangeness.

“I like to say that I’m writing on the borders of the New Weird South,” she explains, “which is connected to the bridge to the Old.”

“So many wonderful, truly iconic American contributions have come out [of Memphis and the South] that couldn’t have come from anywhere else. It’s just this strange alchemy of our dark and bright wondrous history and the way we have related

The New Weird to the geography here. Just the

South is a body music in our language that comes from all of the diff erent cultures of work that that tried to carve out a living is interstitial, out of the land here,” Thomas combining says. “It’s not a static thing, what we do here. It’s always changspeculative fiction ing and moving.” with a Southern omas explains that the New Weird South is a body of work

Gothic feel. that is interstitial, combining speculative fi ction with a Southern Gothic feel. It’s a subset of the New South, a literary movement away from the old “moonlight and magnolias and sticky, sultry, summer nights” clichés. Instead, in embracing the full spectrum of the Southern experience, the movement explores a more authentic, wilder, and weirder landscape.

“You hear echoes, some of our greatest hits, of course, Faulkner, Walker,” omas says. She notes that stories in the New Weird South mode are not necessarily linear, sometimes approaching their truth in a series of concentric circles. “It takes us in a space that is not rooted in the traditional modes of storytelling. ere’s more space for strangeness,” omas continues. “It’s almost like a Southern magical realism, or the marvelous real.”

A LIFELONG LOVE OF LITERATURE

Along with references to P-Funk and magical realism, Thomas mentions a multitude of writers and books in our conversation. “I have always been a reader. My mom taught me to read early,” Thomas says. Her father was in the Air Force, so the family traveled often, before resettling in Memphis when Thomas was 7 years old. Reading was a way to make sure a young Sheree would be caught up wherever they landed next — and to ensure she had easy access to entertainment to keep her occupied.

“The house was full of books,” she remembers. Her grandparents were great storytellers, too. “They were always sharing these amazing stories from their lives, which seemed like foreign lands to me because they were so different,” she says. “I learned about these different things. I learned about tent city when they were trying to vote and got kicked off the land.”

“My parents were big science-fiction fans,” Thomas recalls. “I found my way to Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov.” She particularly liked the Bradbury stories set in small towns, with the mythical hidden everywhere between a thin veneer of the mundane. That and Bradbury’s poetic prose surely influenced the speculative fiction Thomas would go on to one day collect in magazines and write herself.

“I remember the very first time they let me get a library card. It was at the Hollywood branch of the library,” Thomas says. “They would hand me science-fiction stuff because they knew I liked the scary stuff, the strange stuff.” Formative time spent at an Air Force base in White Sands, New Mexico, driving past replicas of rockets and surrounded by snow-white sands, which Thomas describes as looking like an “alien landscape,” surely made the science-fiction genre more appealing — and lent credence to the idea that the marvelous and the mundane were separated by the thinnest of barriers.

In high school and college, Thomas attempted to turn her studies toward more practical career paths — even considering chemistry. “The lab cured me of that,” the author laughs. But an encouraging creative nonfiction professor and a stint working at an independent bookstore helped push her to follow her passions.

“At the time I had like 15 jobs,” she explains. “I was valedictorian in high school, but I was also one of the few young women who was already a mom.” One of those jobs was at Gallery 250, a bookstore and art gallery on South Main, “which was like heaven because I was surrounded by books and art.”

There Thomas met fellow writer Jamey Hatley, a coworker who gave her an issue of Black Enterprise magazine that focused on women publishers. For Thomas, it was eye-opening. So, she says, “I made a plan. I was like, ‘I’m going to New York.’”

While in New York, she worked at Forbidden Planet, a sci-fi bookstore across from The Strand. “I did that and every job you could think of when it comes to writing in a book publishing house.” She wrote jacket copy, drafts of sales copy, reviewed books, and did proofreading and copy-editing. She was totally immersed in a world of words.

AFTER THE BLUES

Now, though, Thomas is back in the Bluff City. “I’m back home, and I don’t think I would have written quite the same collection if I wasn’t home,” she says, suggesting that her roots in Memphis and her time away — both as a child and working in New York — gave her perspective on her hometown.

As for what’s next after Nine Bar Blues, Thomas has a packed dance card. Along with Memphis music historian extraordinaire Robert Gordon and singer-songwriter Alison Mosshart, she will host a Zoom author event from City Lights Bookstore and Third Man Books at 8 p.m. on Wednesday, October 21st. Thomas contributed a short story to the forthcoming collection Slay: Stories of the Vampire Noire, a collection of vampire-themed stories of the African diaspora. If that’s not enough, Thomas is co-hosting the 2021 Hugo Awards Ceremony with Malka Older, where both authors will be special Guests of Honor. And she was recently honored as a finalist for the 2020 World Fantasy Award in the “Special Award — Professional” category for her contributions to the genre.

Even looking at a partial list of the imaginative author’s accomplishments, it’s clear that she has already left a lasting mark on genre fiction. Dabbling as she does in science-fiction, fantasy, and horror, Thomas’ strength is her versatility. She embraces the idiosyncrasies of Memphis and the Delta, wraps them in the cloak of fantasy, writing with musicality that makes her prose read like myths in the making. In her fiction, other realms merge with our world, and immortal record collectors and dancing dragons hidden in crystal computer caves are as real and immediate as anything in the waking world.

Perhaps, for some other hopeful young writer, Dark Matter will, like rocket replicas jutting out of white desert sands, point the way to the stars. Maybe some other little girl will see herself in Nine Bar Blues and, in doing so, realize she, too, has stories to tell. Stories that need to be heard.

Memphis author Sheree Renée Thomas (opposite page) writes with musical prose in Nine Bar Blues; her short fiction was included in the new The Big Book of Modern Fantasy.

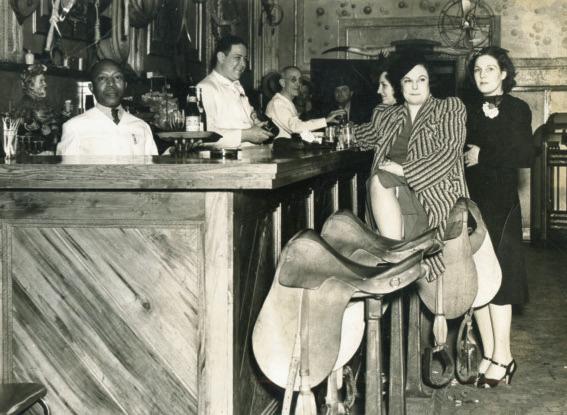

ASK VANCE Where else in Memphis could this possibly be? I remember my older relatives talking about this Stockyards Hotel memorable establishment, but they never took me there. I’m sure they thought it wasn’t a suitable place for Our history expert solves local mysteries: who, what, a young Lauderdale, though perched on a real leather saddle while enjoying an ice-cold Kentucky Nip would when, where, why, and why not. Well, sometimes. have been a treat. BY VANCE LAUDERDALE I don’t know quite what to make of this photo. By that I mean, why was it taken? Although a few people seem to be aware of the photographer, such as the lady standing DEAR VANCE: Where was DEAR T.J.: If someone bothered to write “Memphis” on at right, or the waiter behind the counter, nobody else a bar located in our city the photo, as you say, then it seems they could have is paying much attention. e well-dressed woman where the patrons sat taken the time to write exactly where this place was. perching side-saddle at the bar isn’t even looking at on saddles instead of But it’s possible they were consumed with the same the camera. In other words, it seems to me they are not bar stools? The only clue dreadful lethargy that often overcomes me obviously posing for the picture. scribbled on the back of while I am writing one of my long-winded For a while, But if it was taken so that — many years this old photo is “Memcolumns. Why, sometimes I’ll just drop into Memphis called later — readers of Memphis could admire phis.” — t.j., memphis. a deep slumber, while slumped in my La-ZBoy, and will turn in a story half-fi nished. itself the “Mule the distinctive interior of the Stockyards Hotel (or the café), it doesn’t show much, Most times, nobody even notices. [We have Trading Capital does it? If I squint, I can make out some noticed, Vance. Stop it. — Ed.] I can’t say with 100 percent certainty, but of the World.” cattle horns mounted on a back wall, an electric fan, fl oral wallpaper, and what I believe your old photo shows the unusual interior of is either an old cabinet radio or a jukebox, but that’s the Stockyards Hotel, located in South Memphis at all. e place wasn’t very large, with barely a dozen the northwest corner of West McLemore and Kansas. seats — or saddles — along the bar. With its simple Either that, or it depicts the adjoining Stockmen’s Café. furnishings and lots of bare wood, it defi nitely had a

Bar patrons perched on genuine saddles at the old Stockyards Hotel.

rustic atmosphere, as you might expect from an establishment catering to customers and employees of our city’s stockyards.

Yes, stockyards. Memphis was never in the same league as, say, Kansas City or Chicago, but in the early 1900s we had a booming livestock business here. For a while, in fact, Memphis called itself the “Mule Trading Capital of the World,” though that wasn’t a motto that the Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau bandied about too much. Downtown, a stretch of Monroe Avenue was lined with rows of “mule barns,” quite handsome brick structures where sales took place throughout the year. ose old buildings, most of them vacant for decades, came tumbling down when AutoZone Park was constructed, so you could say the mules made way for the Redbirds.

But the really big stockyards were clustered along McLemore, Trigg, and Kansas in South Memphis. ey were mainly trading centers for horses, cattle, mules, hogs, and even sheep. As far as I know, they didn’t operate as slaughterhouses or meat processing centers. e oldest of these, located at 465 W. Trigg, was Burnette-Carter Company, which claimed it was “one of the South’s largest commission fi rms.”

Others included the Memphis Union Stockyards, Dixie National Stockyards, T.D. Keltner Livestock,

Lightfoot-Howse, William Lundy Company, Wade Tribble, and South Podesta Horse and Mule. At one time, there was even a street called Stock Yards Place, running south off McLemore. Other fi rms were located across town, such as the Dixie National Stockyards on Hollywood.

In 1923, a Mrs. Blanche Stoner purchased the property at 150 West McLemore and opened the Sterling Hotel. Two businesses — a grain company and chemical fi rm — occupied the site, but neither one seems (to me) easy to convert to a hotel, so I assume she built a new structure. e Sterling only remained in business until 1929, when Edward A. Laughter bought the hotel and changed the name to the Stock Yards Hotel (later melding that into one word: Stockyards) while also occupying one of the rooms.

I don’t want to say what year he added the Stockmen’s Café to his enterprise, because I’m not sure of it, but Laughter ran the place until the early 1940s, when other owners took over. If this photo was taken after 1945, by then James B. Goodbar was running the hotel, and Morris and Lula Gammon were in charge of the café.

In 1955, the old hotel became the Terminal Hotel and Café, though I don’t know why it was called that. No railroad or barge terminals are in that area. e name was appropriate, though, in another way. By 1960, the hotel was gone. at entire block of West McLemore was cleared to make way for Gordon’s Transport, a national trucking company.

Over the years, the stockyards also closed, and Memphis lost its claim as a mule-trading center. eir former locations are now parking lots, trucking and shipping fi rms, and home to other industries. At certain places along McLemore, though, old concrete fence posts around empty lots stand as reminders when cattle, hogs, and sheep jammed the stockyards of South Memphis.

Mystery Plate DEAR VANCE: I recently bought a vintage Memphis license plate, which is unusual because it also carries the letters LE and BH. What were these extra initials for — the car owner’s name? — h.g., memphis. DEAR H.G.: This wasn’t actually a license plate. It wouldn’t make sense for everybody in our city — not the way we drive! — to have car tags that spelled out “Memphis.” Just think of the chaos if you were reporting a wreck, or trying to identify a runaway car. What you’ve purchased was called a “plate topper,” probably dating from the early 1950s, and you bolted it above the regular license plate on your car.

And those LEBH initials? ey stood for Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital. Now, I know you might think they should instead be “LBCH” but no, that’s how the good folks at the hospital wanted it, and it was one of their most profi table fund-raising campaigns. You paid extra for those plates, with the money going to the hospital.

I don’t have space here to share the incredible success story of one of this city’s most remarkable hospitals. For that, I recommend e Power of One: Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare: Our First Century (the two hospitals merged in 1995, you see).

But I have space to share this. What began in the 1920s as a women’s sewing circle, which produced sheets and garments for the Leath Orphanage, developed into the Le Bonheur Club — meaning “the good hour.” roughout the 1930s and ’40s, the group came up with innovative ways to raise money to help this city’s needy children, and in 1952 their eff orts paid off with the grand opening of Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital. e “plate topper” campaign began in the early 1950s and eventually expanded into special Le Bonheur bumper stickers and decals that were sold for the same purpose.

Thanks to other successful fund-raising efforts — the Le Bonheur Charity Horse Show (which became a nationally recognized event), profits from a popular toy store on Union Avenue called the Doll House, the hard work of the still-active Le Bonheur Club, and other special events — Le Bonheur ultimately transformed from a one-story building in the Medical Center into the nationally recognized hospital that treats hundreds of young patients every single day. In its own small way, H.G., your old plate topper played a role in that success.

left: Old posts and fences remain from the city’s stockyard district. above: A Le Bonheur license plate topper from the 1950s.

Got a question for Vance?

EMAIL: askvance@memphismagazine.com MAIL: Vance Lauderdale, Memphis magazine, P.O. Box 1738, Memphis, TN 38103 ONLINE: memphismagazine. com/ask-vance