7 minute read

KANAINE: Harrison juggles school, family and business

affiliation when identifying the bodies of victims. That creates inaccurate data and prevents better understanding of violent deaths among AI/AN.

“There is no standard for how to go about identifying American Indian Alaska Natives,” Harrison said.

Two decades ago, NVDRS began collecting data on violent deaths from Oregon and five other states. Harrison is using this data to create a system that she hopes will one day expand to a national level.

While attending the Summer Research Institute at the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board (NPAIHB), Harrison learned about the IDEA-NW Project and how it works to reduce AI/AN misclassification in public health data systems.

The project uses accurate ancestry information to correct public health records and compares different sets of records, correcting inconsistencies for people who appear more than once.

Harrison hopes her research can help find ways to reduce and prevent violent deaths among Indigenous people in the future. She says her own life experience guided her focus.

“When you grow up on the reservation, you see what’s going on,” Harrison said. “You grow up knowing these people and thinking how I could have easily been one of them.”

After she defends her dissertation this spring, Harrison will have earned her fourth degree from Oregon State University. In 2016, she graduated with two Bachelor’s of Science degrees in Biocultural Anthropology and Public Health Management & Policy. In 2018, she added a Master’s of Public Health.

“I’m just excited to get [the data] out there for other people to see my methodology and why it’s important,” Harrison said. “To the average American public [data collection] may not be that important, but when you’re Indigenous from a federally recognized tribe with reservation lands, it’s very important.”

Having access to more accurate data provides vital statistics which ultimately influence how the tribe identifies and allocates resources to the areas of greatest need for their citizens.

A family of entrepreneurs

Harrison credits being a business owner with the flexibility to pursue her studies full-time while raising three young children.

“I probably wouldn’t be this far in my degree without [Kanaine],” Harrison said. “I don’t know what other job I could have done without being my own boss, that would have gotten me the funds needed to be a full-time Ph.D. student with three kids on my own.”

A citizen of the Yakama Nation, Harrison is Cayuse and Walla Walla on her mother’s side and Korean American on her father’s. Growing up, she remembers the overflowing sewing rooms of the women in her family.

Harrison’s mother, Pam, was an artist. Her father, Jimmy, was a businessman. The two met in the late 1970s at Chief Joseph Days in Walla Walla, Wash. Before the birth of their only child, the two ran their own construction business together. They built houses, cabins and motels across the Pacific Northwest.

After the tragic passing of his young wife, Harrison’s father raised his toddler daughter the only way he knew how: on the job site.

Harrison recalls spending countless weekends and summers learning to run a successful business. She balanced checkbooks, worked with her father on numerous projects and watched him make meaningful relationships with his clients.

“I grew up my whole life building houses,” Harrison said. “Understanding how things go together and how to construct something came super easily to me.”

Those skills helped prepare Harrison for the future she would build.

As a little girl, Harrison and her father attended rodeos across Canada and Montana, as well as the Pendleton Round-Up in Oregon. While he was visiting with friends and family, she would admire the fashion.

Anytime she left her home on Kanine ridge was special because she had the rare opportunity to dress up, and she wanted to make sure she did it right. She saw her clothing as a representation of herself.

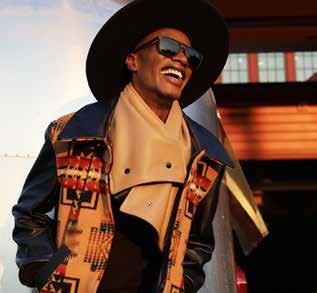

“I’ve always had sort of a unique style,” Harrison said. “I’m not afraid of colors.”

After she graduated from high school she attended Oregon State University until her junior year, when she accepted an internship as a cultural resource manager and consultant at the Hanford Site in Washington. She loved the work and eventually went full time.

At the age of 30, Harrison borrowed a sewing machine, and began developing designs for purses, wallets, shorts and jackets. She experimented with different Pendleton blankets and fabrics.

Soon, Harrison was debuting pieces at the Pendleton Round-Up. Then one year she scored a major hit: shorts made with Pendleton fabric and leather fringe. She knew she was on to something.

Halfway through her pregnancy with her second daughter, Harrison decided to quit her job as a cultural resource manager and consultant, and go back to

Continued from Page 1 college full time. She turned to her sewing machine and a local bootmaker’s leather working machine to support herself through that major change. Putting on the business hat

Harrison launched Kanaine after returning to Oregon State University in 2013, selling her pieces on Etsy and building her platform on Instagram, which now has over 25,000 followers.

In 2017, Harrison launched Buckaroo Cowls, her best-selling piece to date. She said the design originated from the desire to keep her kids warm when they refused to keep their coats and hoods on.

“I was like, ‘You know what? I’m gonna make something that has buttons that snaps on it, and you can’t get it off with your little hands,’’’ she said with a chuckle. “I made those for them and then I was like, ‘Oh, I have a couple of scraps, maybe I’ll make some bigger ones.’”

These pieces, like all of Harrison’s other handmade goods, are unique. Because of the way she cuts the Pendleton blankets, no two pieces are alike.

Like her tribe, Harrison has forged a relationship with Pendleton Woolen Mill. She says the company calls her when they have extra limited or specialty blankets.

“I get blankets that no one else sees,” Harrison said.

Popular as apparel and eventually as a standard of value for trading among numerous tribal nations, Pendleton Woolen Mills blankets have become synonymous with Native Americans even though Pendleton isn’t Native-owned.

However, Harrison’s preference to use Pendleton fabrics comes from a long lasting personal connection to the blankets and the history they hold to her people. With its original mill located less than five miles from the Umatilla tribal headquarters, the blankets have been a part of her tribe’s cultural landscape since the early 1900’s.

“If you look at the history of the local tribes here, the blankets were made to trade with the Indians,” Harrison said.

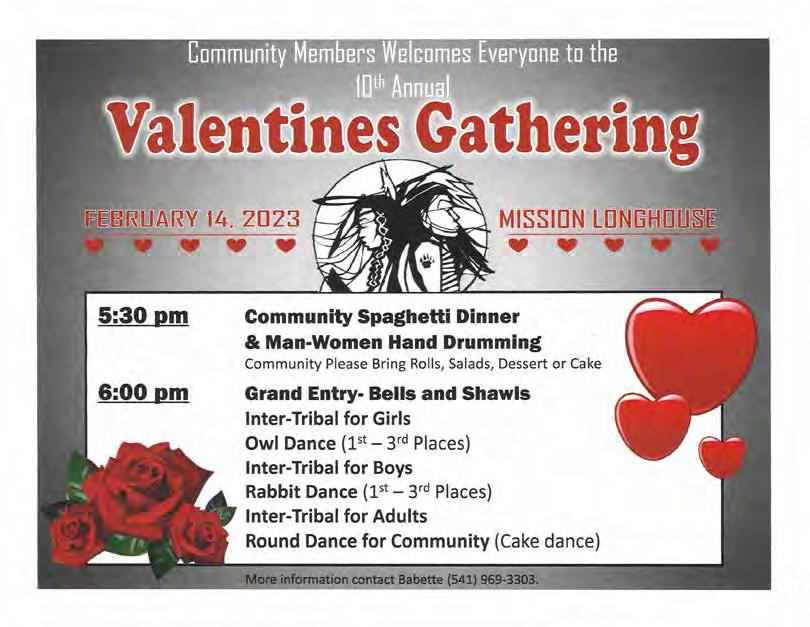

17 years, February 11th HAPPY ANNIVERSARY!

“To

CONTINUED From Page 4

Indigenous communities and Pendelton have a complex relationship. For more than 100 years, Pendelton has profited off of tribal designs and names. That has sparked debate over the widespread problem of cultural appropriation and how it intersects with cultural appreciation.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, over one hundred years after Pendleton began operations, that the company began hiring Native artists and compensating them for their authentic artwork and designs.

But Harrison says there is more to it than that.

Over the generations, Pendleton blankets have become prized posses sions for many Indigenous families. The blankets are used as gifts during giveaways, at graduations or when giv en to swaddle a newborn. The blankets also hold meaning during various cer emonies such as being wrapped around a new couple during their wedding or used during burials.

Harrison recalls many markers of her life being established on a Pendleton blanket.

“You can just see that history of reci procity a little better when you’re from here,” she said. “I can definitely also see the other side of the coin, where people say they take these names and designs without consulting the tribes or without that money going back to the tribes.”

Harrison thinks there is always room for improvement, but said she has seen the company shift in recent years toward increased cultural competency.

Today, Pendleton’s partnerships include the American Indian College Fund, the Native American Rehabilita tion Association and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American In dian. And the company hires Indigenous artists to create new designs.

When asked why she uses majority Pendleton fabrics, Harrison said the qual ity of the materials has a big influence.

“I have used other blankets,” Harrison said. “But the quality of the blankets and the tightness of the weave that comes from a Pendleton blanket lends itself much better to being cut.” the team in 2017. The organization provides Native entrepreneurs access to tax professionals and training on digital marketing and newsletter automation, among other things.

Harrison creates heritage products that hold value, show history and tell stories, said Amber Faist, Coquille tribal citizen and technical assistance program manager at Oregon Native American Chamber (ONAC).

“We have so much richness and vibrancy in our communities,” Faist said. “Sydelle is a positive representation of who we are as Native entrepreneurs in the Pacific Northwest region.”

Over the years, Harrison has worn a construction hard hat, vintage Navajo

Happy Birthday to the two best kids in the whole world! We love you so much Kiya & Grey!

Love, Mom, Dad & Simon

Are you 26 or younger?

There's still time to protect yourself against 6 types of cancer and genital warts by getting the HPV vaccine. All young adults 26 and younger need the HPV vaccine. And the sooner you get the vaccine, the better it protects you against cancer. Persons aged 15 are able to consent to get their own vaccinations.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE HPV VACCINATION VISIT WWW.CANCER.ORG

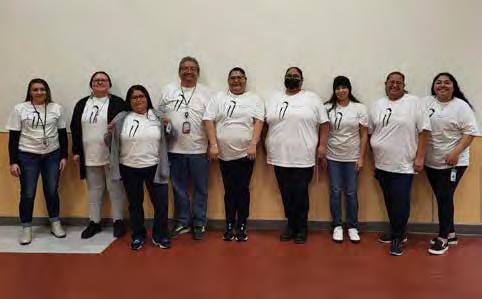

Kátkaatma Wápšašni Boys with Braids

The CTUIR Education Department set forth to create a project with the objective to recognize, encourage and support the Indigenous men, young men and boys with long hair of this community. With the hopes of also fostering a sense of pride and empowerment throughout the community, neighboring communities and schools. On January 12, 2023 that objective came to reality. The young children of the community wore T-shirts to support the cause. Children from the ages 0 to 8 years and Education staff wore their t-shirt in honor of our men, young men and boys that wear long hair. This is one of the many projects that the Education Department has planned to promote cultural identity and to make those important cultural connections within our own community, schools, and neighboring communities.

Beginning April 1 Oregon will start to mail information to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Eight-year-old Tipiyelehne Wildbill said, “ Mom, I got the coolest shirt today!” The t-shirt reads, “Inmí Tútanik, Inmí wáqišwit,” “My hair, My life.”