5 minute read

SYMPHONY

History of the Colorado Symphony e Colorado Symphony has a rich history that dates back to 1922 when its predecessor, the Civic Symphony Orchestra, formed in Denver. Prior to 1922, there were several semi-professional music acts scattered across Denver, but no formal orchestra. At the height of the Great Depression, Helen Marie Black, publicist for the Civic Symphony Orchestra, helped form the Denver Symphony Orchestra in 1934. Her goal was to consolidate the local musicians, boost audience attendance and guarantee union wages. e orchestra held its rst concert at the Broadway eater in Denver on Nov. 30, 1934, led by Conductor Horace Tureman.

After a 55-year run, the Denver Symphony Orchestra disbanded in 1989 as the result of nancial hardship. It led for bankruptcy on Oct. 4 of that year. Musicians left the Denver Symphony Orchestra for the newly-formed Colorado Symphony, which played its rst concert on Oct. 27, 1989. e following year, the two groups merged to form one organization.

Since its inception in 1989, the Colorado Symphony has had ve recorded principal conductors, beginning with Marin Alsop in 1993. e current principal conductor, Oundjian, has served in the role since 2022.

One hundred years ago, the symphony in Colorado was di erent than it is today. From a small group of semi-professional local musicians, the Colorado Symphony has grown in size and in the diversity of its members. e Symphony currently has 80 full-time musicians, representing more than a dozen countries around the world.

The Colorado Symphony today Denver is a vibrant city full of people who yearn to experience the arts. From taking in contemporary paintings at the Denver Art Museum to seeing hip hop concerts at Red Rocks, and from watching classic works performed by the Colorado Ballet to laughing at stand-up acts at Comedy Works, locals love to get out and experience the best of Colorado arts.

“Twenty years ago, people said Colorado was just a great place for the mountains — a great place for sport. at is what people were interested in. I feel there has been a huge shift in what people in Denver want,” Oundjian said. “We had the biggest crowds ever at Boettcher Concert Hall last year. Nobody moves to Denver to just sit inside and watch TV. Colorado is all about getting out there.” roughout the 100 years of symphonic music in Colorado, performances and o erings have shifted and grown to meet the needs and wants of the changing audi- ence. e Colorado Symphony not only performs classical works from composers like Mozart, Brahms and Tchaikovsky, but it also performs contemporary pieces, pop songs and soundtracks from fan-favorite lms. is year the Colorado Symphony will have several performances outside of the classical genre. ese include “Star Wars: A New Hope in Concert,” “Disney in Concert: Time Burton’s e Nightmare Before Christmas” and “Home Alone in Concert.” ere will also be performances for children like the “Halloween Spooktacular,” “Elf in Concert” and “Peter and e Wolf & e Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.”

“In the last 10 years, there has been a tremendous shift from the Colorado Symphony. It is one of the great leaders in the evolution of programming. ey collaborate with musicians from every possible musical genre and from lm,” said Oundjian. “We have abso- lutely cutting-edge music, world premieres and also the beautiful performances of the great classics. Sometimes we perform these classics juxtaposed to a contemporary piece. We try to keep the program very alive so that the people are attracted to as much of it as possible. You’re not going to appeal to every person in Denver, every night. We try to present, over the course of the season, all of the great elements of the musical art form.”

Oundjian said the Colorado Symphony’s milestone could not have been reached without the longstanding and overwhelming support of the community.

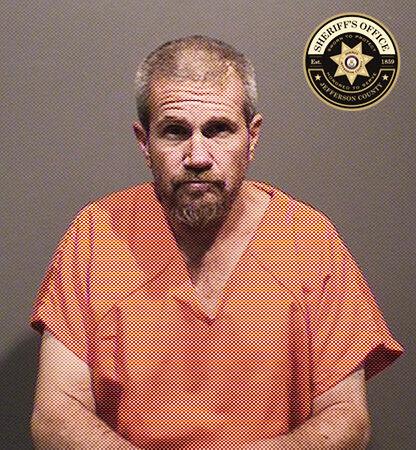

“ is season carries special signi cance as we celebrate 100 years of music and look ahead to the next century of music making in Colorado,” said Oundjian. “ is celebration belongs as much to you and our state as it does to our orchestra, and we can’t wait to share the excitement with you all season long.” the RV, and Montoya told investigators Harris didn’t come back to the hotel room that night and didn’t answer his phone. e next morning, the RV was gone and Harris wouldn’t tell Montoya where he’d been.

Erickson said both Harris and Hire’s phones were recorded at the Wooly Mammoth lot between 3-3:30 p.m. March 26.

A few hours later, the Golden Police Department contacted Harris at Home Depot, where he was transferring items between Hire’s Jeep and Montoya’s Jeep. At the time, GPD didn’t know he was connected to Hire, and arrested him on outstanding warrants in Denver.

When JCSO investigators examined the items Harris had when he was arrested, they found a jacket with Hire’s blood on it, Erickson explained. Harris also had Hire’s cell phone and keys to storage containers inside Hire’s RV.

Investigators also reviewed messages and calls Harris had sent and received while he was in jail, where he coordinated with friends to try to hide the evidence, such as the RV itself and Montoya’s Jeep, Erickson said.

In searching Montoya’s Jeep, investigators found a .22-caliber revolver that’s believed to be the murder weapon. It had a single spent casing in it while the others were live rounds, and the red shot matched the bullet fragments found in Hire’s body. It also had both Hire and Harris’ DNA on it, Erickson continued.

Among the friends Harris reportedly coordinated with to hide evidence, one told investigators about how he and someone else had tried to move the RV from the Wooly Mammoth lot twice, and both times had bad feelings and “felt sick.” us, they ultimately left the RV where it was, and deputies discovered it and Hire’s body a few days later, on April 14.

Erickson said the autopsy found that Hire died from a single gunshot to the head, and that the gun was red at close range, but couldn’t give an exact distance.

Defense’s arguments

Harris’ defense attorneys admitted there was strong evidence on the possession of a weapon by a previous o ender charge, but contested the rst-degree murder charge. ey said there was speci cally little to no indication of any premeditation or planning, and stressed how there wasn’t any physical evidence Hire was murdered in the RV.

Erickson con rmed there was no visible blood spatter in the RV, and all the surfaces and areas JCSO tested were negative for blood. ere also wasn’t anything to indicate a gun had been red inside it, or that it had been cleaned, the defense argued.

“ ere’s no evidence this homicide even happened in Je erson County,” one of Harris’ attorneys said. “ … e prosecution hasn’t presented any evidence as to where the homicide might have occurred.”

Carrithers explained how, in preliminary hearings, he’s required to view evidence “in the light most favorable to the prosecution.” us, he found there was probable cause that Harris murdered Hire sometime between March 25-26, and scheduled Harris for his Sept. 27 arraignment.

++ 0 10 15% %%