10 minute read

INEQUITIES

FROM PAGE 16 would that be worth today?” ere, he raised Wilson’s father, who was not able to attend college.

Many Black veterans faced issues using the programs o ered by the GI Bill. ey often could not access banks for home loans, were excluded from certain neighborhoods and faced segregationist policies. Instead of a home in the suburbs, and despite his service to his country, Wilson’s grandfather wound up in low-income housing.

“ e only physical thing that I have from (my grandfather) besides his DNA is a collection of hats … that shouldn’t have been the case,” Wilson said. “I should have more from him than his name, his genes and some hats.”

In that era, federal authorities also made color-coded maps that re ected the practice of restricting access to home loans in certain areas, largely based on race. is practice is known as “redlining.” People of color were also excluded from obtaining housing through “racially restrictive covenants,” or text written into property records that was used to prevent people of certain races from purchasing certain homes.

Some exclusionary policies, which have been documented in the Denver area, left a toll that’s evident in communities of color today.

Family wealth is a good measure of that. In 2019, the median White family in the country had about $184,000 in wealth compared to just $38,000 and $23,000 for the median Hispanic and Black families, respectively. at’s according to data from the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances. ese numbers speak to the notion of generational wealth. Generational wealth is anything of nancial value that is passed from one generation to another — including money, property, investments, valuable heirlooms or businesses.

“ ink about the wealth that was created during (the ‘40s and ‘50s) that White families have been able to leverage generation after generation, either the Colorado rate — many by a large margin, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

In Cherry Hills Village, a wealthy suburb that borders Denver, the number of Black Americans amounts to 0% of the population. Just a few miles away, the population is 17% Black and 44% White in Aurora, one of Denver’s most diverse suburbs.

Aurora is an exception, not the rule. Many of Denver’s other older suburbs are much less diverse.

Several Adams County cities have large Latino populations, but even though they’re suburban, the cities still tend to have lower-income neighborhoods closer to Denver and more expensive housing farther north.

Still, the suburbs don’t entirely look like they used to, according to Yonah Freemark, senior research associate at the nonpro t Urban Institute, based in Washington, D.C.

“Overall, the suburban parts of the nation have transformed dramatically and have become more diverse over time,” Freemark said. at’s in terms of age, ethnicity and race, and income, Freemark added.

In the future, some suburbs will likely undergo a “steady transformation” toward increased mobility, such as having more public transportation, Freemark said. Other changes could include more e orts to get people walking and biking, with the transition of suburban storefronts and strip malls into more walkable neighborhoods, he added. e path forward for the suburbs may involve a continued increase in diversity of residents, Freemark said. But that depends on whether states and the federal government will expand support and requirements related to a ordable housing, Freemark said.

“We’re going to need signi cant public investment and changes to public law to support those outcomes,” Freemark said. “Otherwise, little is going to change.” e a ordability issue transcends race, with many people simply priced out of the housing market and those who are in it struggling to a ord what they need for their families. In 2010, the median single- family home price in metro Denver was about $200,000. It was roughly triple that as of 2022. to send their kids to college, to be able to start a business, to writing a check for their loved ones to be able to have money for (a) down payment in order to buy their own home and continue that generational wealth transfer,” said Aisha Weeks, managing director at the Dear eld Fund for Black Wealth, a Denver area group that emphasizes homeownership. “ at wasn’t available in mass for Black and African American families.”

Coupled with a ordability is an availability issue that local rules play a role in exacerbating. Large-lot zoning — planning for houses to be built on large portions of land — is one major issue. In other words, there are too many large homes being built and too few starter homes, leaving prospective rst-time homebuyers with few options, perhaps even relegated forever to renting.

“If you have a very expensive largelot neighborhood, you don’t get young families,” Rogers said. “You don’t want your community to box out young families or new Americans. Or, you end up with, in a sense, a retirement community, and there’s nothing wrong with a retirement community, but you don’t want your entire community (to be that). You want kids to be in your schools.” e long-term trend of rising housing prices plays a role, too, as wages fail to keep pace with housing costs. at “has the potential to continue to widen inequality and even perhaps embed it,” Rogers said.

A family’s primary residence is typically their most valuable asset, according to the National Association of Realtors.

It’s not just the monetary value of a house and property that adds to wealth. ere are tax bene ts for homeowners and people can borrow against a home’s equity to start a business or to help with unexpected bills. Homeownership also provides stable housing, which has been shown to positively impact health and educational achievement. ese factors can, in turn, improve a person’s economic prosperity.

Trying to change the equation

e Dear eld Fund for Black Wealth o ers down-payment assistance loans with no interest and no monthly payments up to $40,000 or 15% of the purchase price for Black homebuyers. is program helped Wilson and his wife buy their home in Aurora.

“We acknowledge that there’s a generational wealth gap, and so Dear eld Fund is walking alongside our clients and borrowers to say, ‘We will provide that down-payment assistance,’’’ Weeks said.

In addition, the fund also o ers advice and education on how to build wealth.

“We know that there are so many pitfalls and just things that, as a community, we have not learned at the dinner table like our counterparts,” Weeks said. “ ere’s a lot of power in the knowledge information transfer that happens within other communities that we need to make sure that families are understanding.” at issue of being at the proverbial dinner table comes up a lot for communities of color. Without an example to follow, some rst-time homebuyers don’t know where to begin. According to Alma Vigil, a local loan o cer assistant, families who do not own homes often do not pass along information about how to own and maintain a home.

To address this challenge, the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority o ers homebuyer education programs to teach Coloradans nancial skills and the steps to homeownership. ese classes are o ered in English and Spanish in an e ort to remedy language barriers, which can add challenges for potential homebuyers who do not speak English.

“ ere’s very (few) Spanish speaking loan o cers,” said Vigil, who is Hispanic and speaks Spanish herself. “ ere are some that claim to speak Spanish, but they’re not very uent. So it becomes a huge problem, especially with lack of understanding.” e issue isn’t just one faced by Hispanic and Latino communities. A report by the National Coalition for

In order to close the gaps, some lenders across the metro Denver area provide services in Spanish. A list of Spanish-speaking lenders can be found on the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority’s website.

Asian Paci c American Community Development found language barriers are also often a challenge for members of the Asian American community when pursuing homeownership. In addition to conversations with lenders, real estate paperwork and documents rarely come in languages other than English.

Debt-to-income ratio

Over the last couple of years, Brandon Stepter, a community consultant, has been working in Broomeld. In an e ort to bring more people of color into the community, Stepter looks at housing infrastructure, housing practices and community practices.

Stepter and his wife, Gabrielle, both of whom are Black, have been renting in Aurora but have recently been looking to purchase a home.

“We thought we would be pretty solid in that regard and we both make a decent amount of money,” Stepter said. “We thought we would be able to start looking, even in this market, to try and nd an equitable home that ts our budget.” e Black Business Initiative is a Denver-based organization that focuses on economic equity in the Black community.

Stepter, who also works as a healthcare administrator, and his wife, who works for a technology company, said they are trying to gure out how to pay o their student debt so they can get a home loan within the next couple of years.

“I think right now what we’re seeing is a lot of younger African Americans who are in copious amounts of student debt and that has been preventing them from owning a home,” Stepter said.

Debt-to-income ratio is often a signi cant barrier for Black people who are looking to buy a home because that number is assessed when underwriters are deciding whether or not to give a mortgage, according to Jice Johnson, founder of the Black Business Initiative.

“In America, you are encouraged to graduate high school and go to college,” Johnson said. “Typically speaking, because you don’t have access, when you go to college you’re not going to pay for college outright. Instead, you’re going to get a student loan … So it increases the debt side of your ratio by a lot, oftentimes preventing you from purchasing a home.”

Black college graduates tend to owe thousands of dollars more in student debt, on average, than their White peers. According to a 2016 report from the Brookings Institution, the amount can exceed $7,000 at the date of graduation.

Black and Hispanic workers also tend to be paid less than their White counterparts, according to many studies on the subject. In 2020, Black workers in Colorado earned 74% and Latino workers in Colorado earned 71% of the hourly earnings of White workers, according to numbers from the 2020 ve-year American Community Survey.

“So you go to school, you get the degree, which is what you’re supposed to do to get the high-paying job,” Johnson said. “Now you come out and you have debt and also your income isn’t as high as it should be. So, your entire debt-to-income ratio doesn’t allow for you to purchase a home.”

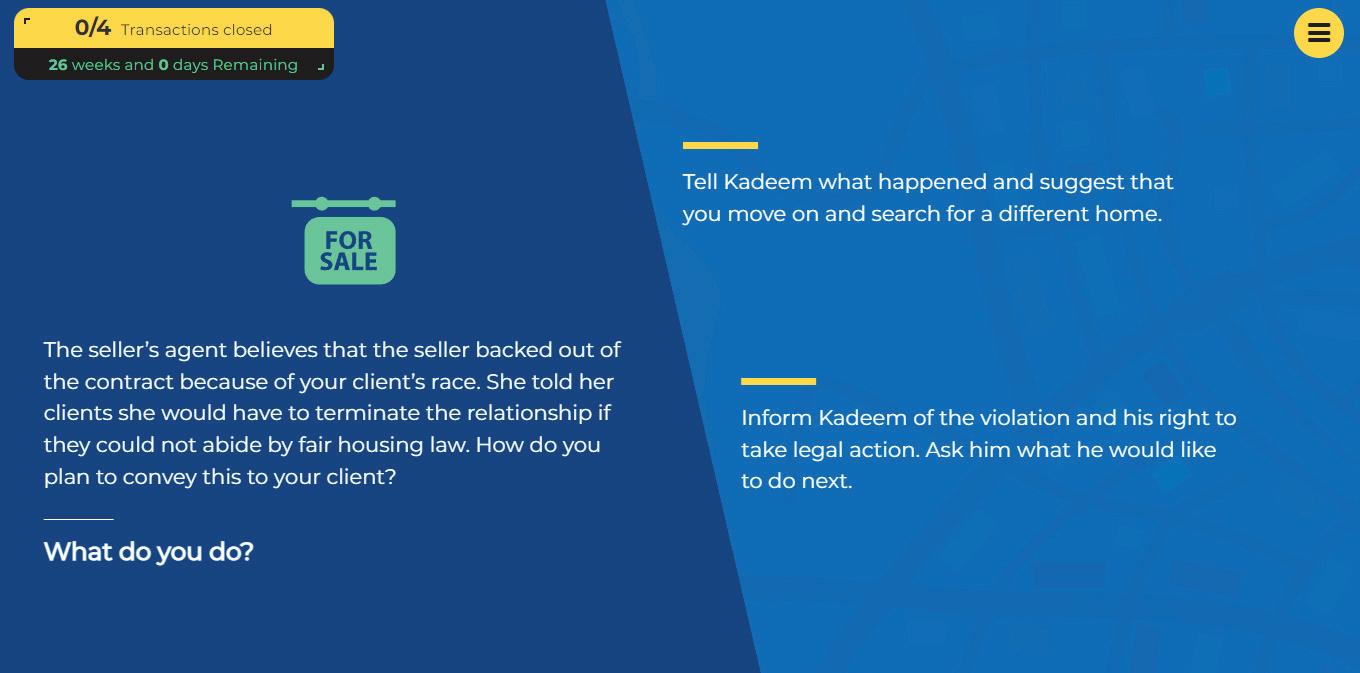

Discrimination

In a national statistical analysis of more than 2 million conventional mortgage applications for home purchases, a data-based news publication called e Markup found that lenders were 40% more likely to turn down Latino applicants for loans, 50% more likely to deny Asian/Paci c Islander applicants, 70% more likely to deny Native American applicants and 80% more likely to reject Black applicants compared with similar White applicants.

Even for families of color that may not struggle immediately with wealth and knowledge disparities, discrimination persists in the housing market. People of color are often treated di erently in appraisals, lending practices and neighborhood options.

Stories about what that looks like in the Denver area abound. Johnson of the Black Business Initiative lived in Westminster before moving to Aurora. When she was staging her home to sell, her real estate agent gave her some advice.

“It was encouraged for me to make sure I had no family photos up,” she said.

Meanwhile, she visited homes for sale that had photos of White families.

Johnson said it was good business advice. Her Black Realtor, Delroy Gill, understood the landscape and was looking out for her.

“ at’s my Realtor trying to get me top dollar,” she said. “ e question is, why would (leaving) my photos prevent me from getting top dollar?”

Gill said the practice of taking down photos removes potential hurdles that could occur for his clients. For Black clients, race is sadly one of those hurdles that could a ect how appraisers, inspectors and potential homebuyers view the home, he said.

“We do know racism is a real thing,” he said. “And it exists in every facet of life. So therefore, when you are faced with the unknown, it’s better to make the adjustments based on how society is versus taking the risk of creating more damage on Black wealth by them receiving less funds for their homes.” e advice Gill gave Johnson was not unique. Paige Omohundro, business development manager at the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority said her team heard similar stories in recent focus groups with real estate agents, nonpro ts, lenders, housing advocates and people trying to achieve homeownership in Black and African American communities. She said these stories were shared by members of Hispanic and Latino communities as well.

Gill said that because of his precautions, discrimination rarely impacts his clients’ sales. One time, however, the preparation was not enough.

A couple of years ago, Gill was working with an interracial couple to sell their home in Parker. When the appraiser arrived, the Black husband was leaving the property.

“I own investment properties in the area, so I know the area very well,” Gill said. “And I used to live in the neighborhood. So the value that we gave to the house was very appropriate — and the appraisal came in $100,000 less (than our value).”

According to Gill, the buyers, who were White, decided to pay the extra $100,000 out of pocket because they knew the original asking price was fair.

“ e agent and the buyers thought that the price was reasonable and that the appraiser made a big mistake,” Gill said. “We tried to dispute the appraisal and failed. He said he’s not going to change it.” e study found that, based on over 12 million appraisals from Jan. 1, 2016 to Dec. 31, 2020, 8.6% of Black applicants receive an appraisal value lower than contract price, compared to 6.5% of White applicants. In the study, Freddie Mac said it would be valuable to conduct further research to understand why this gap exists.

Gill said the homebuyers noted that the low appraisal was probably due to racial discrimination.

According to a 2021 study by Freddie Mac, a government-sponsored mortgage-buying company, this experience was not rare. Black and Latino mortgage applicants get lower appraisal values than the contract price more often than White applicants, according to the study.

In a report by the National Fair Housing Alliance, however, personal stories like that of Gill’s clients

FROM make the case that the appraisal gap comes from racial or ethnic discrimination. e lower value appraisal report explicitly compared the home to others in a nearby predominantly Black neighborhood, even though that’s not where the house was located.

One of these stories, originally reported by the Washington Post, was about a mixed-race couple in Denver. An appraiser greeted by the White wife valued the house at $550,000, whereas one greeted by the Black husband valued it at $405,000.

Since 1968, housing discrimination