4 minute read

VOUCHERS

Jack Regenbogen, deputy executive director at the Colorado Poverty Law Project, said he and other advocates consider this behavior to be a form of discrimination.

“ ey’re not saying anymore, ‘We won’t accept Section 8,’ but they are discriminating based on the amount of income,” Regenbogen said.

Although many voucher holders can’t meet income requirements, Marosy from the Denver Metro Fair Housing Center said the voucher itself is a dependable sign that the tenant will be able to pay their rent each month.

“If you look at it from the landlord’s point of view, this is a guaranteed source of income,” he said. “ ey know for a fact that this individual has this voucher and that money will be there for months and months to come.” is legal blurriness has created a situation where landlords can reject a voucher holder for not making three or more times the full rent amount in income.

But House Bill 20-1332 sets no limit to the income level a landlord can require. And for people with vouchers, there’s no clarity about whether a minimum income requirement applies to the whole rent, or just the portion of rent a voucher holder is paying out of pocket.

A new law rough months of lobbying and testifying, the Colorado Coalition for the e Colorado Apartment Association, a leading state group for landlords, was a vocal opponent of the bill. Spokesperson Drew Hamrick said the income requirement cap — which will allow people to spend 50% of their income on rent — will set tenants up for failure.

Homeless and the Colorado Poverty Law Project worked with legislators on a new law this year, Senate Bill 23-184, that addresses income requirement barrier for voucher holders. It will go into e ect in August.

“It caps the minimum income requirement at two times the cost of rent,” Wilde said.

“Anyone signing a contract that they’re promising to pay that much of their income in rent is going to default under it,” he said. “No one can afford to do that.”

Hamrick said landlords do not care about the source of a tenant’s money — but they care that they get paid.

In landlords’ eyes, he said, the housing voucher program adds the risk of additional expenses they might not be compensated for. ese potential expenses include rent lost while o - cials inspect a unit to see if it meets federal standards. He added there are other risks, like the chance that a tenant might not be able to pay for repairing property damage. Instead of mandating that landlords accept vouchers, Hamrick said, legislators should work to make the program more nancially attractive for landlords.

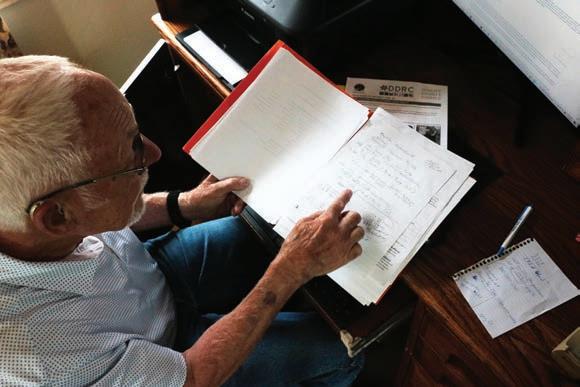

George Vonesh shows handwritten math problems calculating payment standards, income levels and his grandson’s voucher subsidy — complex calculations required to find his grandson a home.

He said the new cap is not a sustainable decision for rental housing providers, who will have to accept tenants more likely to default on rent. He added that more defaults would likely make rents rise across the market over time.

“ e Colorado legislature has substituted their own business judgment for the judgment of the entire market and made a bad business decision here,” he said.

Regenbogen, however, said he thinks people paying half their income on rent will still be able to make ends meet. Low-income people, he said, have always had to be resourceful — and housing is a necessity they deserve the opportunity to have.

“(Paying half of one’s income on rent is) not ideal, but what’s worse was the previous status quo where if people weren’t earning an arbitrary multiplier of what rent is, then they could very possibly nd themselves either in the homeless shelter or on the street,” he said.

He added that the new number re ects a reality in Colorado — where more than half of households are rent-burdened, meaning they are paying more than the recommended 30% of their income on rent, according to recent U.S. Census Bureau data.

For people with vouchers, the new law also clari es that minimum income requirements must only apply to the portion of rent the tenant pays out of their own pocket.

In addition, it prohibits landlords from considering the credit score of an applicant who is on a voucher. Wilde said credit, like the minimum income requirement, has historically been a barrier for voucher holders in nding housing.

Hope for Justin

Vonesh said the new law is good for people at low income levels like Justin.

Since voucher holders generally pay 30% to 40% of their income on rent, the vast majority will now always qualify in terms of income.

“I think (the law) will have a fairly signi cant positive impact,” Vonesh said, re ecting on the times Justin has been turned down on the grounds of income. “ at new provision, I think, takes that o the table.”

Vonesh said the more he knows and understands the laws, the more he is feeling prepared and empowered going into conversations with apartment managers.

“I was just waiting for them to say ‘We don’t accept vouchers,’” he said, describing one recent meeting. “I was ready to pull out my printed-out copies of the statutes that are all highlighted.”

But people who don’t know their rights don’t have that opportunity to stick up for themselves, he said.

To help educate more tenants and landlords on the rights and rules related to housing discrimination, the Denver Metro Fair Housing Center launched a campaign in April about source-ofincome discrimination.

“Most prejudice is rooted in the lack of knowledge,” Marosy said. “We’re optimistic that as we get more knowledge out about the voucher program, we’ll see a decrease in the discrimination that we’ve been seeing against voucher holders.”

As months have gone by, laws have been passed and Vonesh has gotten help, he has maintained hope for Justin — but it hasn’t been easy.

With the number of apartments that have not worked out for his grandson, Vonesh was hesitant to say one law would x the whole process.

“I think some of these folks can be pretty creative if they really don’t want to accept vouchers,” he said.

But the new law is a step forward, he said.

Armed with his stack of papers and knowledge of his rights, Vonesh is dedicated to continue trying — for the sake of himself, for the sake of Justin and for the sake of other Coloradans who have struggled to put a roof over their heads.

WHY CHOOSE A VECTRA BANK CD:

•

• Predictable: Maximize your savings for an established period of time.

• Attractive Rate: Get a competitive APY on your money!

Visit a branch today or contact your local banker to get started. Visit www.vectrabank.com/CDSavings to learn more.