15 minute read

Going to 5

EDITOR’S COLUMN

Recently, State Rep. Bob Marshall did exactly what he said he was going to do when he ran for o ce — he introduced a bill that would require large counties to expand from three- to ve-member boards of commissioners. If the bill is approved, that would mean Douglas County will go from three to ve commissioners.

Arapahoe County already has ve commissioners, which means they would not be impacted by the bill. However, Arapahoe County operates without a lot of in-commission ghting, has good discussion and debate and is a great example of why a ve-member board can be a lot more functional.

When it comes to party lines, I would like a better balance of Republicans and Democrats on the Arapahoe board, given there is currently only one Republican, but that’s not a huge complaint.

In Douglas County, the current commissioners are great evidence of why a three-member boards is not good in representing a county with 360,000 people and growing. e argument against the bill is that it “creates more government,” not less. I get not wanting more government, but is having two more commissioners added to a currently dysfunctional board a bad thing?

I have never been a fan of the all-yes boards. I like my elected boards to have a balance of voices and opinions. If all members of a council, commission or school board have the same thoughts, beliefs and ideals — you will get a lot of rubber-stamp voting without thoughtful discussion and debate.

Local city and town councils, with fewer residents than all of Douglas County, currently have more elected ofcials looking out for their best interests.

In Douglas County, residents currently have George Teal and Abe Laydon deciding where and how money is spent. ey are making decisions on zoning, land use and water. If Commissioner Lora omas does have an opposing view or opinion — it doesn’t seem to matter as the two men on the board have clearly formed an alliance. is alliance means if one supports a project — the other will get in line to do the same. ese are schoolyard games that should never been the norm on a local, elected board. is alliance has cost taxpayers plenty of money in approving investigations against omas that have yielded nothing more than tens of thousands of dollars in wasted taxpayer dollars.

At the very least, two more commissioners being asked to approve another frivolous investigation might ask questions and vote against it.

With two more commissioners, decisions might still end the same way, but I bet there is more discussion, fewer alliances and probably a healthier representation of what residents in Douglas County deserve.

What I love about Rep. Marshall introducing the bill, House Bill 23-1180, is that he can’t be bullied. He is at the state level and the two-member majority can’t just quash it. Do I think the bill will pass? It’s early and hard to say. e argument of having more government oversight could win out in halting it in its tracks. However, I do hope our elected o cials at the state level give it true thought and consideration.

If it is passed in the 2023 session, counties that would be a ected by the bill are Je erson, Larimer, Douglas, Boulder, Pueblo and Mesa, all of which are counties with three commissioners.

elma Grimes is the south metro editor for Colorado Community Media.

LINDA SHAPLEY Publisher lshapley@coloradocommunitymedia.com

MICHAEL DE YOANNA Editor-in-Chief michael@coloradocommunitymedia.com

THELMA GRIMES South Metro Editor tgrimes@coloradocommunitymedia.com

NINA JOSS Community Editor njoss@coloradocommunitymedia.com

Letters To The Editor

Support 300

Support Ballot Measure 300. Every citizen that wants to have a democracy should support this measure because the city government does not want to listen to its citizens. e city is so afraid of this they want to pass Resolution 10-2023. It is a resolution to tell you to not even consider the ballot measure. Even though, by the time you see this council may have passed it, we all should write council to tell them it was wrong to even put forth such a resolution. I wrote the city council the following about this resolution and their disdain for the voter’s voice; it is not about the ballot measure but exempli es the council’s stance in opposition to your (you the citizen and voter’s) voice and directly shows why you should vote yes for the ballot measure.

To pass Resolution 10-2023 opposing Ballot Measure 300 is to refute all the principles of democracy as written in both the State and Federal Constitutions. e resolution is the council body saying: rst, that the City Council has no respect for the voice of “We e People.” Second, that council does not believe in the right of the citizens to disagree with the City Council. And third, that you the City Council disavows and repudiates the right of citizens to petition even as guaranteed in old city charter, ARTICLE VI. INITIATIVE AND REFERENDUM. It says, “Any proposed ordinance may be submitted to the Council by a petition signed by registered electors of the City equal in number to the percentage hereinafter required.” e petition that resulted in Ballot Measure 300 met those requirements and was written with the city Attorneys guidance to assure it met the law and the Charter’s intent, and the with assistance of the city Clerk to make sure it was written in a way that could easily become part of the City Charter and Code. In short, the Littleton City Council’s stance against this petition is a claim that the City Council should rule with absolute, autocratic authority. Any member of the City Council that votes to approve this resolution should be completely ashamed of themselves and understand that they are making a claim of dictatorial-like power! is is as un-American as it gets.

For the sake of our democracy, every voter should speak out against the resolution and vote for the ballot measure.

Michael Goldberg Littleton

Look under the legalese

Artful use of language is something most enjoy. It makes us smile, and we each have our favorites. But some aspects of the language arts are less endearing.

Most nd the lengthy “whereas” statements found in o cial government documents less than enjoyable reading. Sometimes this actually informs, but it can also hide things and mislead.

Littleton City Council’s February 7 Resolution No. 10 illustrates. It urges a “no” vote on Ballot Question 300. Voters should take a careful look — both at what is there and for what is missing.

TAYLER SHAW Community Editor tshaw@coloradocommunitymedia.com

ERIN ADDENBROOKE Marketing Consultant eaddenbrooke@coloradocommunitymedia.com

AUDREY BROOKS Business Manager abrooks@coloradocommunitymedia.com

ERIN FRANKS Production Manager efranks@coloradocommunitymedia.com

One does not have to be a fan of courtroom drama to appreciate verbal skills used to craft this resolution. Even Raymond Burr would crack a wry smile. And few would want to argue the resolution’s factuality. What’s not there, however, is another story all voters should know.

Legalese (de ned by Cambridge as legal language “di cult for ordinary people to understand”) in the resolution’s fth “Whereas” states: “the City of Littleton already conforms to State Law in requiring at least 5%, as referenced in C.R.S § 31-11-104, of the registered electors to advance petitions and initiatives.” is statement artfully avoids the impetus for Question 300. Of course, as a Home Rule Municipality — a rmed by the resolution’s fourth “Whereas” — Littleton “has the right and authority to govern its own elections and signature requirements.” But greater candor would have revealed that, for years, the city has actually imposed “greater” requirements than the “at least 5%” of registered voters required by State Law.

Indeed, for referendum petitions, the city requirement is twice the state minimum, 10%. And for initiative petitions, it requires three times the state minimum, 15%. Now it appears the city has grown even more fearful that voters might call its undesirable decisions into question (i.e., referenda) and push it to take neglected actions residents want done (i.e., initiatives).

But why? Why would the City of Littleton be so afraid of having residents make their voices heard? Not a few residents perceive they are being inadequately represented by o cials’ heads lopsidedly turned more to outside interests than to caring for Littleton’s existing character, its neighborhoods, and its quality of life as well as curtailing high-density development and its adverse impacts.

Amazingly, that powerful block, emplaced and supported by outsider interests, is now telling residents how to vote. Don’t be misled. Vote “yes” on Question 300.

John Marchetti Littleton

Housing and diversity

Kudos to Colorado Community Media for a piece of ne local journalism with “ e Long Way Home” series examining Colorado’s housing crisis. e January 26 articles detailing racial inequities in Denver’s suburban communities like the Littleton area, where I live, provide important insight — and highlight the need for all of us to redouble e orts for social change.

As the series illustrates, Littleton and surrounding towns didn’t become lily-white by accident. Government policies assured racial and economic segregation via redlining, racially restrictive covenants, and large-lot zoning. Today, Denver metro is highly racially segregated, ranks 13th among the most highly economically segregated urban areas, and 40th among U.S. large metro areas for upward mobility of below-median-income families.

SEE LETTERS, P21

Columnists & Guest Commentaries

Columnist opinions are not necessarily those of the Herald.

We welcome letters to the editor. Please include your full name, address and the best number to reach you by telephone.

Email letters to letters@coloradocommunitymedia.com e meth closures in Colorado made national news, from People magazine to e New York Times. Public reaction vacillated between accusing the libraries of causing hysteria to wondering how far society has sunk.

Deadline Wed. for the following week’s paper.

Pikes Peak Public Library District said Jan. 19 it would remain open as samples are taken from all 15 locations in Colorado Springs as a “proactive action” though there was no known meth exposure. It later scaled back, deciding to test only the bathrooms at three of the most popular branches.

Of the four libraries that closed, only Boulder has reopened, though the bathrooms are sealed o by a temporary wall and plastic until they are cleaned by a professional meth lab remediation company. e Boulder library was closed for three weeks. Englewood has been shut down for nearly a month, and Littleton for two and a half weeks. Arvada closed more than a week ago.

Boulder library director David Farnan doesn’t regret closing the doors, even though he said he learned from local and state health o cials within a few days of the closure that no one’s health was ever at risk. After 14 incidences of drug use in about three weeks, he’d already had a policy in place to shut down the bathrooms and not let anyone — even the cleaning crew — enter if there were fumes in the air.

But just because no one’s health was at risk, that doesn’t mean it’s acceptable, he said.

“We have to do everything we can to prevent this from ever happening again,” Farnan said. “We can’t have a public library and have meth use going on in the bathroom. at’s just a nobrainer.”

So the library will again nd a way to adapt. e plan is to keep the restrooms closed to the public, except for children accompanied by their parents and people who have a medical condition. It’s the best way Farnan sees to preserve the library’s mission to serve all, whether they are parents and kids coming to story time, seniors using the internet or people who sleep outside.

“It’s one of the few places where anyone can go, everyone is treated with decency and you don’t have to buy anything,” he said. “ at’s rare. e value of having a public place is extraordinary.”

Colorado’s standard for meth contamination isn’t based on public settings

Here is how many reports of patrons a ected by meth contamination the libraries received: Zero.

Two Boulder library employees reported feeling “dizzy” after walking into a smoke- lled room in late November and were checked out by paramedics, but both had normal vital signs and no evident symptoms of narcotics exposure.

And for public health experts who have studied meth exposure, that doesn’t come as a surprise.

“I think the health risks when we nd that amount — by design — are negligible,” said Mike Van Dyke, whose research on meth exposure helped establish the state’s decontamination procedures and sampling requirements.

In Colorado, a space is considered contaminated if meth residue is detected at levels above 0.5 micrograms per 15.5 square inches. e threshold is based on a child being exposed for a long period inside a home.

“It was really established for the worst-case exposure, which would be a toddler living 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in a contaminated home crawling over carpets, putting their hands in their mouth, doing all of those things,” said Van Dyke, now a professor at Colorado School of Public Health.

But public restrooms are a far di erent setting than one’s living room.

Nonporous tiled oors and countertops make it easy to wipe o meth residue, which is very water soluble. People don’t spend much time in a public restroom and typically try to avoid touching surfaces to limit the spread of germs.

“So let’s say you touch a surface, you wash your hands before you leave. You’ve generally washed the vast majority of meth o of yourself even if you were exposed,” he said.

“ ere’s really low opportunity for exposure.” resholds requiring a space to decontaminate detected meth residue vary per state, with some states having much higher limits than Colorado. In Wyoming, for example, the threshold requiring decontamination is set at 1.5 micrograms, according to a 2019 review by e International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Even so, libraries are being held to an “inappropriate” standard not designed to measure meth exposure in public settings.

“ e only standard they have is one that’s inappropriate, and from a riskmanagement perspective, their only real recourse is to clean it up to that one standard that exists,” Van Dyke said.

At the libraries in Boulder, Littleton and Englewood, meth residue that exceeded the state’s threshold was detected in the exhaust ducts in the bathrooms and on bathroom surfaces. Cleanup will cost tens of thousands. Englewood received an estimate of $38,000 to $45,000 for state contractors to decontaminate the library, according to an email sent to its sta . Boulder’s bill is tallying $105,000 so far, with an additional $68,000 in cleaning costs expected.

But few, if any, have standards set for public spaces.

Colorado’s threshold is used for all spaces where meth is detected, but it was designed around longer exposure times, speci cally where someone is exposed to that level of meth for 24 hours, then reduced by 25 as a safeguard for toddlers, said Dr. Karin Pacheco, an allergist and occupational medicine expert at National Jewish Health.

“And that’s the case for most of these government levels — there is a protection factor built in to account for the more vulnerable people who may be exposed,” Pacheco said. “We need to look at where it’s being used and make sure that that usage is reduced, but the actual exposure itself, it’s unlikely to be harmful.”

Symptoms after being exposed to meth for a short period of time can include irritability, jitteriness and a fast heart rate. For kids, symptoms will likely be more severe.

Tests are limited in what they reveal — meth contamination could be present for long periods of time before it’s ever detected. Like in air ducts, for example.

“Exhaust vents really show what’s been in the air for a week, two weeks,” Pacheco said. “It doesn’t tell you the time of the exposure.”

Libraries found needles, white rocks, bag of meth ere’s no state regulation that requires public spaces to be tested regu- larly for meth, so testing won’t happen unless there is reason to believe meth is being used in a speci c area. is story is from e Colorado Sun, a journalist-owned news outlet based in Denver and covering the state. For more, and to support e Colorado Sun, visit coloradosun.com. e Colorado Sun is a partner in the Colorado News Conservancy, owner of Colorado Community Media.

At Boulder Public Library, the rst to close for cleanup, sta suspected drugs were being used inside the restrooms at the main branch downtown for months.

Incident reports e Sun obtained under the Colorado Open Records Act show that 19 people were banned from the library for 364 days under drug-related suspensions last year — with most of them in November and December with seven suspensions respectively.

Burned aluminum foil was found in the stall Dec. 1. On six separate occasions that month, sta complained of a strong chemical smell coming from a stall where someone was inside. Library workers heard people discussing drugs in the bathroom stalls.

Last January, police found a woman inside a bathroom stall with a needle in her arm and three other syringes with meth in them, reports from the library show. Six months later, a patron told the library’s security that they needed help and turned in a bag of meth.

In September, someone reported that drugs were being used in the second- oor men’s bathroom and guards said they started experiencing symptoms from the smoke and fumes. Sta closed, the restrooms, but the person left the library before employees could issue a suspension.

Similar problems were reported in Englewood, where last July, workers and patrons saw a man using a small, white tube to snort a white powdery substance o a table in the back of the computer lab. In September, the city’s library sta found a pile of burned tin foil, a capped syringe and a plastic capsule of saline inside a handicap bathroom stall. Sta also found a backpack with needles and drugs inside the lobby, where security footage showed a man and a woman using the drugs minutes earlier.

More than once, patrons slipped sta notes saying that they believed drugs were being used in the men’s bathroom.

Less than a month before shutting down, a patron said he found what he thought was “a cooking kit.” Inside the small, black zippered case, there were several blades, a small plastic tube and a few small white rocks.

Days later, a nurse visiting the library advised workers to shut down the bathrooms because two people had been smoking fentanyl in the men’s room and the smoke was at dangerous levels.

BY CORINNE WESTEMAN CWESTEMAN@COLORADOCOMMUNITYMEDIA.COM

While working out at a gym in Golden recently, someone approached Ty Scrable and asked if he was associated with Colorado School of Mines. Scrable had to explain that, no, he’s just a Golden resident.

Unfortunately, Scrable said, this isn’t the rst time it’s happened.

“I get that a lot,” he said. “People think I’m a student, professor or tourist because I’m Black.”

Systemic racism stubbornly remains in Golden. But, as Scrable said, it has morphed from Ku Klux Klan demonstrations in the 1920s and racist housing policies in the 1940s to something less overt but still widespread and endlessly frustrating.

Because White people make up the overwhelming majority in the city and, thus, are seen as the norm, Scrable said, “many people don’t view me as part of my own community.” e newspaper, which now is part of Colorado Community Media, isn’t immune to biased coverage. is report is the product of its journalists attempting to examine the paper’s coverage of the Black community since the Civil Rights era and own up to its mistakes.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the summer of 2020, many cities and newspapers across the United States have started reckoning with their pasts, examining how they’ve contributed to systemic racism, learning what they can do to be more inclusive and fair. e Golden community has started the process, and now it’s the Golden Transcript’s turn.

Since 1866, the Golden Transcript — known as the Colorado Transcript for its rst 103 years — has been a record keeper for Je erson County. While its stories are extensive and valuable, the paper contains original and reprinted content that was harmful to the Black community and other marginalized groups.

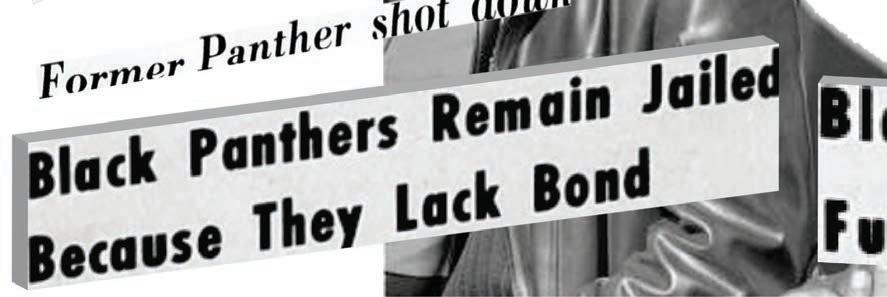

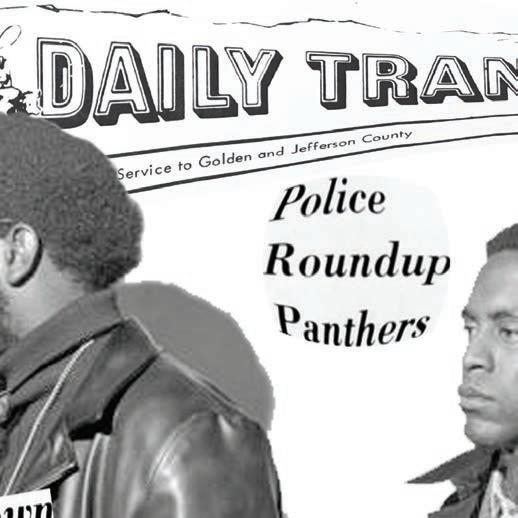

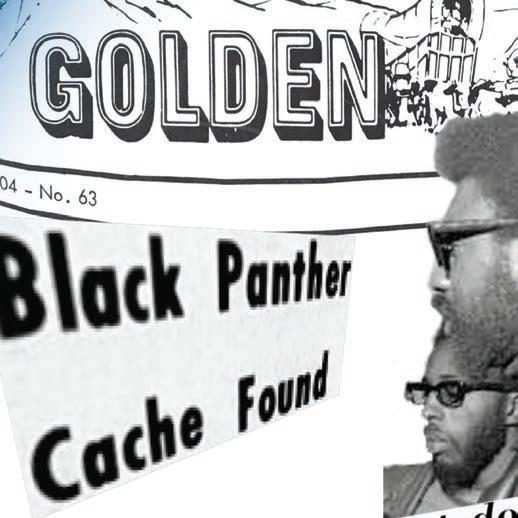

Just one example is its coverage of the Black Panther Party, a group that gained national attention in the late 1960s for its response to policing in Black communities across the country.

Between 1969-1971, the newspaper published approximately 170 articles that referenced the Black Panther Party. Nearly all of these articles

BEYOND THE GOLDEN TRANSCRIPT: Our efforts to reconcile racial mistrust begins with this story

In our newspaper this week, you’ll see an article about the Golden Transcript. It’s one of two dozen newspapers owned by Colorado Community Media, which also owns this paper. The article tackles the issue of systemic racism in the Transcript’s pages.

The idea for the project started in 2020, when the Colorado News Collaborative, Colorado Media Project and Free Press convened the Black Voices Working Group, which was made up of Black leaders, community members and journalists. The group addressed media coverage and focused on how to improve trust in mainstream media among the Black community. Acknowledging past harm was the No. 1 recommendation made by the group.

A few months later, I attended a Denver Press Club event where Jameka Lewis, a senior librarian at the BlairCaldwell African American Research Library, illustrated biases in mainstream local media coverage of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s and ’70s while exhibiting rare prints of the Black Panther Press. Many of Lewis’ examples came from the Transcript. Most articles were wire stories from other cities, but editors still chose to run them, affecting perceptions of the party in Golden.

We pursued and were awarded a grant from the nonpartisan Colorado Media Project to explore, uncover and analyze this issue in the form of the special report that is in this edition of your newspaper.

Our newsroom, which is predominantly White, also participated in the Maynard Institute’s diversity, equity and inclusion Fault Lines training along the way. West metro editor Kristen Fiore was a speaker at the Advancing Equity in Local News convening with journalists from publications like the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Washington Post to talk about this project.

We believe this story is important beyond Golden — and we hope to spark conversations in our communities across the Denver area about race and inclusion and how our news coverage impacts those issues.

Linda Carpio Shapley is publisher of Colorado Community Media, which runs two dozen weekly and monthly publications in eight counties. She can be reached at lshapley@coloradocommunitymedia.com