5 minute read

MEDICAID CLIFF SURVIVING THE

the gardens proper. In fact, most of the conservation work is o site.

By documenting plants broadly across the southern Rockies to the Denver metro area, the gardens can determine how healthy a landscape is based on biodiversity in the area. e gardens’ teams conduct an annual census of a few rare species for the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service so these entities can make informed decisions based on scienti c data of how their management is impacting these species.

e Denver Botanic Gardens has discovered that local biodiversity has varied, with some areas seeing greater or less biodiversity over time.

“A lot has to do with urbanization, so it is important to protect greenways which allow for wildlife and plants to thrive,” said Neale. “A healthy ecosystem is one that does not require human intervention in order to continue.” e horticulture team at the Denver Botanic Gardens has worked with local municipalities to design sustainable landscapes to support biodiversity. In Lakewood, for example, publicly- owned medians were landscaped using native plants with low water requirements. e Denver Botanic Gardens even participates in sustainable agriculture by blending agriculture with biodi-

A regional conservation program at the Denver Botanic Gardens assesses existing protected areas and the need for action to create wildlife corridors. is program measures areas that are already protected and determines where more wildlife protections are needed to provide a cohesive habitat for wildlife, allowing animals to travel through urban areas without having to interact with people.

Biodiversity on a global scale

In December, Neale went to Montreal, Quebec, Canada, to attend a global conference with a focus on biodiversity. At this conference, called the United Nations Biodiversity Conference of the Parties, various groups had speci c topics where they discussed measurements that will dene milestones and determine when targets and goals have been reached. At this conference, the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was nalized, which establishes goals to conserve as much biodiversity as possible. is framework is set up so that all participating countries, regardless of wealth, will have guidelines and resources to support healthy biodiversity. While the U.S. is not an o cial signatory on the GBF, there is plenty that people can do locally to promote biodiversity.

What local residents can do to support Denver’s biodiversity

Biodiversity is seen in Denver’s urban areas. Various trees, birds and reptiles can be found along greenways, open spaces and areas that have been left untouched or abandoned. e High Line Canal is the most commonly used urban greenway in Denver and runs 71 miles from Highlands Ranch to Denver International Airport. According to Neale, the canal includes multiple ecosystems as it spans from a higher elevation to short grass prairie. Denver Botanic Gardens has documented a couple hundred plant species along the Highline Canal.

Plant native plants

“Nonnative plants can have a positive e ect in an ecosystem, but they don’t have as strong of a relationship with the local ecosystem as native plants do,” said Neale.

Nonnative plants have zero connection to the local area’s birds, butteries, ladybugs, bees and other insects because they have not evolved in the same location. According to Neale, plants from di erent areas that are not local to Colorado don’t support the local food chain because they are unfamiliar. Additionally, bees don’t pollinate nonnative plants.

Although native plants are the preferred choice, it is still more important to have a diverse landscape, even if nonnative plants are the only option.

“A dense array of organisms is the highest priority,” Neale said.

Don’t plant invasive plants

Many invasive plants were brought from Asia and other areas as ornamental plants. Once removed from predators, the plants are able to thrive and take over.

“ ings that go unchecked can be really harmful,” said Neale.

Neale points to the treeline around Grand Lake in Granby.

“ e impact of the mountain pine beetle has been particularly astounding,” Neale said.

Being a Colorado native, Neale has noticed the treeline turn gray due to beetle kill, resulting in dead - potentially re prone - pine trees.

Neale suggests purchasing plants from local garden centers with sta knowledgeable about Coloradospeci c plants that will support local biodiversity.

Take pictures, not things

While enjoying nature, in addition to “leave no trace,” it’s just as important to leave wildlife in nature. When people pick owers or take things home as a souvenir, not only is there less left for others to enjoy, there is an impact on wildlife.

“ ese small acts have long-term impacts on the system,” said Neale.

Taking a rock may seem harmless, but rocks are shelters and habitats to worms and insects. Flowers are where seeds are stored. Every time someone picks a ower, fewer seeds are left to disperse in that area, resulting in less wild ower reproduction.

Instead of taking objects from nature, Neale suggests to take pictures and actively engage and contribute to science by using the iNaturalist app. Uploading wildlife pictures to the app can help the user identify plants, while making a record of the species. is provides a crowd-sourcing way of tracking global biodiversity and there have even been some new scienti c discoveries made via the app, said Neale.

Get involved

A hands-on way to help local biodiversity is to participate in programs like the Denver EcoFlora project, which encourages participants to pay attention to their environment, learn species names and contribute to the documentation of biodiversity. In April, a three-day global contest called the City Nature Challenge will take place. is will challenge people in cities across the globe to document the most species. As part of the event, people can join in on hikes and “bioblitzes” hosted by the Denver Botanic Gardens.

`Give your yard over to nature’

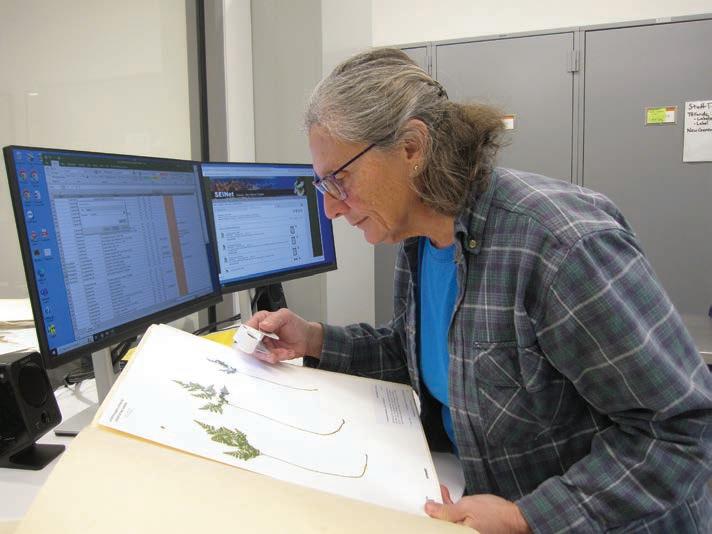

Another way to get involved in biodiversity conservation is to become a volunteer at the Denver Botanic Gardens. Sue Janssen of Centennial was an aerospace engineer and wanted to keep the science side of her brain active after retiring, she said. So in 2016, she became a weekly volunteer. As a volunteer, Janssen does some eld work but primarily helps in the herbarium, supporting botanists by collecting and processing plant specimens. e knowledge Janssen has gained from volunteering has helped her have a better understanding of how to manage her own land. With time, her property has become a sanctuary for local wildlife and an environment that supports local biodiversity.

“Give your yard over to nature,” Janssen said. “Nurture it and change the world.” is is something Janssen learned from Doug Tallamay’s book, “Bringing Nature Home.” e property has become home to many wildlife species including various birds, raccoons, muskrats, foxes, coyotes, deer and bunnies. Since changing the landscape, Janssen has noticed an increase in birds, which is directly related to a higher accessibility of food: fruit growing on trees and insects from host plants with visiting moths and butter ies, for example. Janssen has even seen new plants growing, including a clump of native bluestem grass.

It is too expensive to regularly irrigate the two-acre property, so Janssen and her husband removed the bluegrass lawn and replaced it with bu alograss, which is a native grass. Now they only have to mow their yard twice a year. ey also planted an orchard of apple, peach, plum and cherry trees, as well as wild owers and other native grasses.

Janssen encourages others to join in her quest to support local biodiversity.

“If everyone planted one native plant in their yard, it could transform the city.”