12 minute read

Artful Sukkahs

Past and Present

by goldie gross

Two-tone canvas tarps mounted on tubular poles. Vinyl-covered T Two o-t ton ne ca anvas tarps mounted on tubular poles. Vinyl-covered fiberglass panels held together by a matte aluminum frame. A fiberglass panels held together by a matte aluminum frame. A roll-up bamboo mat retrieved from the corner of the basement: rollupbamboomatretrievedfromthecornerofthebasement: these are the trappings of the modern Sukkah.

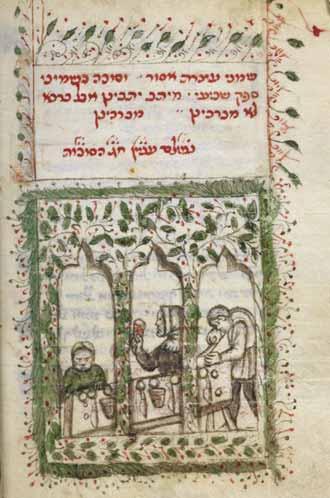

But were things always this way? The answer is a resounding no. The Sukkahs that dot Jewish backyards, roofs, and porches are inherently modern inventions, a contemporary way to celebrate an ancient holiday. So how were Sukkahs built in past generations? One of the best ways to study the practices of the past is through art (their halachic status is beyond the scope of this article). For looking at medieval times, illuminated manuscripts serve as a helpful guide for getting an idea of how holidays were celebrated. Engraved works (prints) rose in popularity with the rise of printing and also offer a more detailed picture than miniature paintings in manuscripts can offer. Finally, we are lucky to have some surviving examples of Sukkahs from Eastern Europe that weren’t destroyed during the Holocaust. A number of Italian illuminated manuscripts contain illustrations of Sukkahs. One Italian siddur from 1383 shows several suggestions of a Sukkah, but not a complete picture of how it would have been built [Figure 1]. In this illustration, we see three pointed trefoil arches. These elements belong to a Gothic style of architecture, something of an “ecstatic Classicism.”1 This style is a sort of revamping of more traditional forms with an emphasis on soaring arches, columns, and points, a “mysticism made possible by advances of engineering” that began in the middle of the 12th century.2 Whether this painting is a peek from the square-headed window of an Italian home or a peek into an architecturally complex Sukkah is hard to tell.

Figure 1: Forli Siddur, 1383, British Library

The plant-based sukkah, the one smuggled out of Germany, the attic sukkah in Belarus, the stained glass porch Sukkah in Poland and Sukkah City in Manhattan

Another illustration in an Italian manuscript from 1374, several years earlier, shows us a more complete Italian Sukkah. This painting shows both a Sukkah and a man in profile with a lulav and esrog [Figure 2]. This Sukkah, which looks like it could be hexagonal in shape and is only visibly furnished with a bench, is very botanical, reflecting Ezra’s commandment to “go out to the mountain and bring olive leaves and leaves of oil trees, myrtle leaves, date palm leaves, and leaves of plaited trees, to make booths, as it is written.”3 Indeed, a Sukkah must be made of organic materials, as it is written directly in Devarim: “You shall make yourself the Festival of Sukkot for seven days, when you gather in [the produce] from your threshing floor and your vat.”4 This has been interpreted to mean that “the Sukkah must be from materials similar to whatever you’ll pick up from your threshing floor.”5 We see that the Sukkah in this painting adheres to the pasuk, using plant matter that was hardly altered for this construction. Another work in a northern Italian machzor shows both a completed Sukkah and a Sukkah in progress [Figure 3]. Interestingly, although these Sukkahs have no walls, they are written underneath text that lays out specifications for what the walls of a Sukkah should be.6 The completed Sukkah on the left shelters a family, and one of its sides features an arch for additional support. The boys on the right appear to be a medieval variation of modern-day Sukkah-building bochurim.

Figure 2:

Figure 2 (above): Pisqei Rabbi Yeshayah Aharon, 1374, British Library Figure 3 (below): Northern Italian machzor, c. 1465–1470, National Library of Israel

Figure 3:

Moving forward a few hundred years, we find Sukkahs that bring illuminations to life by painting them on their walls in the tradition of painted wooden shuls popular in Europe between the 1600s and the 1800s (many of these shuls were destroyed during the Holocaust).7 One surviving Sukkah is the Deller Sukkah, commissioned in the second half of the 19th century by the Deller family in Fischach, Germany [Figure 4]. This Sukkah was smuggled out of Germany in 1935 by a family immigrating to Israel that took it with them in a crate packed with their belongings.8 One wall features a painting of Jerusalem copied from a lithograph by rabbi and artist Yehosef Schwartz; on other walls are scenes of Fischach and its local people.9 Interspersed amongst these scenes are images of various holidays copied from seforim printed in Sulzbach in 1826.10

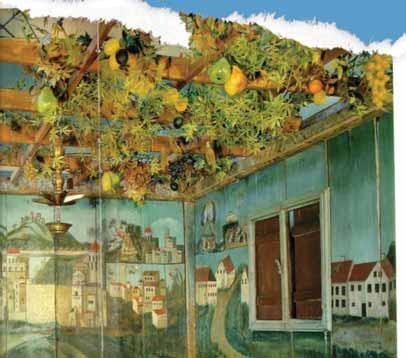

Another Sukkah like this, which currently lives in Paris’s Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme, also connects Israel with the old country. Unlike the Deller Sukkah, the Sukkah in Paris, created in southern Germany or Austria for a wealthy family in the middle of the 1800s, more visibly links these two distinct places, smoothly transitioning Jerusalem gates to European houses in a corner of the Sukkah [Figure 5].11 The painting of Jerusalem here, too, was inspired by a lithograph by Rabbi Yehosef Schwartz.12 When these Sukkahs were filled with families and tables, the lower portion of their walls would be hidden from sight, which explains why these paintings only begin a few feet off the ground. Both of these Sukkahs clearly emphasize their commissioners’ connection to their towns and to Israel, and also bring a sense of permanence to a structure designed to be temporary. These Sukkahs’ numbered panels reveal their intended longevity;13 they were designed to be taken apart and put back together year after year, and one can only wonder how many more Sukkahs like these were commissioned and lost.

While these two Sukkahs both have

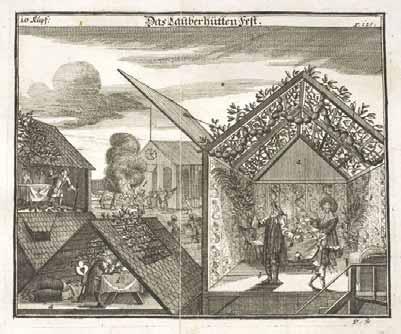

extraordinary interiors, their exteriors are plain. What architectural innovations were developed in pursuit of the ideal Sukkah? Today, some choose to install retractable roofs or skylights in their homes that allow them to turn a room into a Sukkah as needed. This practice dates back to at least the 1700s. In the 1724 edition of Paul Christian Kirchner’s Jüdisches Ceremoniel, an expository book on Jewish customs in Germany in the early 1800s, a series of etchings prepared by Johann Georg Puschner illustrate Jewish life.

Figure 5: Sukkah, mid-19th century, painted conifer, approximately 87 x 112 inches, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme, Paris,

In the book’s print about Sukkos, we see attics built specifically for use during this holiday [Figure 6]. Furthermore, in photography, we see that this was also the custom in some parts of the shtetl, for example in Ivanava, now in Belarus [Figure 7], and in Eisiskes, now in Lithuania [Figure 8]. In parts of Poland, especially in Płock, where Jews were once required to file permits to build Sukkahs, a number of 19th century Sukkahs still stand today.14 These Sukkahs jut freely from the sides of houses or are supported by pillars, and one of the most interesting Sukkahs still in existence from Płock long stood at the corner of Tumska & Królewiecka streets [Figure 9]. The intricate stained glass and cozy construction would have made this Sukkah a treat to look at in its heyday. This dilapidated Sukkah was acquired by the Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw in 2017, which intends to restore and

Figure 4: Deller Sukkah, second half of the 19th century, oil on wood, approximately 79 x 114 x 114 inches, The Israel Museum

Figure 6: Johann Georg Puschner, Das Lauberhütten Fest, c. 1924, print, in Jüdisches Ceremoniel (Nürnberg: Peter Conrad Monath, 1724), University of Chicago Library

Figure 7 (above): Sukkot in Iwanowa, 1916, postcard, National Library of Israel Figure 8 (below): Yitzhak Uri Katz, Members of the Lubetski Family Stand Outside their House, 1931, photograph, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

exhibit the Sukkah.15

Now, in the 21st century, it can feel like a lot of the attention to detail and labor that made Sukkahs unique is lost. This is not without its perks: having a Sukkah is easier now than ever, and thus more accessible to more Jewish people. However, at times, it feels as though nearly all Sukkahs follow similar unimaginative templates and are more like temporary tents than sacred structures.

There have been a number of initiatives in recent years to try and combat this. Sukkah City is perhaps the best-known of these efforts [Figure 10]. Twelve winning Sukkahs were chosen from over 600 entries to stand for two days in Union Square, with the People’s Choice winner (chosen from over 17,000 ballots) remaining up for the duration of the holiday.16 The twelve winners, some Jewish, some not, totally reimagined what a Sukkah can be within the confines of Halacha (using some loopholes that I don’t quite have the certification to qualify as either Kosher or not), including a Sukkah topped simply by a log with holes drilled through it [Figure 11].17 The People’s Choice Sukkah, designed by Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan, is an explosion of marsh grass and phragmites [Figure 12]. The architects designed this work, titled Fractured Bubble, with a Sukkah’s ephemerality in mind, drawing inspiration for this design from a bubble.18

Sukkah City had a far-reaching influence, provoking a large response from both Jewish and secular media sources. For several of the architects, this was their first time building a Sukkah; doubtlessly, for many visitors, this was the first time they interacted with a Sukkah. Sukkah City also served as an impetus for a wave of Sukkah design competitions that continue until today. Similar competitions have popped up in Detroit, Dallas, Saint Louis, and Toronto.

Figure 9: Sukkah in Płock on the corner of Tumska and Królewiecka streets, JewishPlock.eu

Closer to home, Rabbi Herschel and Raiza Malka Hartz of Chabad of Inwood organized Sukkahwood for the past three years (unfortunately, this year’s event was cancelled due to the pandemic) [Figure 13]. Rabbi Hartz, inspired by Sukkah City, felt the need to organize Sukkahwood because he noticed that for many people, “art is something outside the purview of a religious lifestyle.”19 Rabbi Hartz and Raiza Malka, who received her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, sought to rectify this by founding Jewish Uptown Arts and hosting events like Sukkahwood and the Uptown Jewish Film Festival in order to “put on the same programming that other Jewish organizations who are not inclined religiously [put on]... but put it on with very proud, Jewish,

Figure 10

and family-friendly programming.”20ly programming. ” Indeed, as the curator for the first and rator for the first and second Sukkahwood, I can say with ood, I can say with (admittedly biased) confidence that d) confidence that Sukkahwood and events like it help us events like it help us re-imagine and relate to our history and ate to our history and traditions, particularly how changes in arly how changes in the circumstances that governed Jewish that governed Jewish life changed the way we celebrate our way we celebrate our holidays today. ys today.

Figure 11: Kyle May and Scott Abrahams, LOG, 2010, cedar wood and laminated glass. Figure 13: Shayna Denburg, Chained Together, 2017, wood, hooks, rope, plants, chain, and paint

Goldie Gross is an artist, curator, and student of Art & Business at Baruch College where she founded The Art Club. A member of The Met Collective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, she curated and co-produced exhibitions for the Jewish Art Salon and the annual Sukkahwood.

Endnotes

1 Denis R. McNamara, A Crash Course in Ecclesiastical Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 2017), 38. 2 ibid., 38, 171. 3 Shulamit Laderman, “The Sukkah as Sacred Architecture,” in Jewish Religious Architecture, ed. Steven Fine (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 357-358; Nechemiah 8:15. 4 Devarim 16:13.

5 Tzvi Freeman and Chananya Groner, “Sukkology 101: Sukkah Building Basics From the Inside Out,” accessed August 24, 2020, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/2720149/jewish/Sukkology-101.htm. 6 Laderman, “The Sukkah as Sacred Architecture,”358. 7 Mimi Levy Lipis, Symbolic Houses in Judaism: How Objects and Metaphors Construct Hybrid Places of Belonging (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011), 49.

8 Richard McBee, “Deller Succah Paintings At The Israel Museum,” RichardMcBee.com, September 30, 2001, https://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1945/item/deller-succah-paintings. 9 “Sukkah,” The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, accessed August 24, 2020, https://www.imj.org.il/en/ collections/199807.

10 “Sukkah,” The Israel Museum. 11 “Hut for the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkah),” Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme, last modified May 14, 2020, https://www.mahj.org/en/discover-collections-key-works/hut-for-the-feast-of-tabernacles-sukkah. 12 “Hut,” Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme. 13 Lipis, Symbolic Houses in Judaism, 50. 14 “The Sukkot of Płock,” JewishPlock.eu, Nobiscum Foundation, October 13, 2019, https://jewishplock.eu/en/ plock.eu/en/ the-sukkot-of-plock/.

15 “The Sukkot of Płock.”

16 Ariel Kaminer, “Injecting a Sense of Play in Religious Tradition,” New York Times, Sep. 24, 2010, https://www. 2010, https://www. nytimes.com/2010/09/26/nyregion/26critic.html.

17 Heather Ring, “Sukkah City,” Archinect, September 17, 2010, https://archinect.com/features/article/101234. tures/article/101234. 4. 18 Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan, “Fractured Bubble,” Sukkah City, accessed August 24, 2020, https:// 24, 2020, https:// sukkahcity.com/sukkah/fractured-bubble.php. 19 Rabbi Herschel Hartz, voice message to author, August 23, 2020. 20 Rabbi Herschel Hartz, voice message to author, August 23, 2020