11 minute read

News

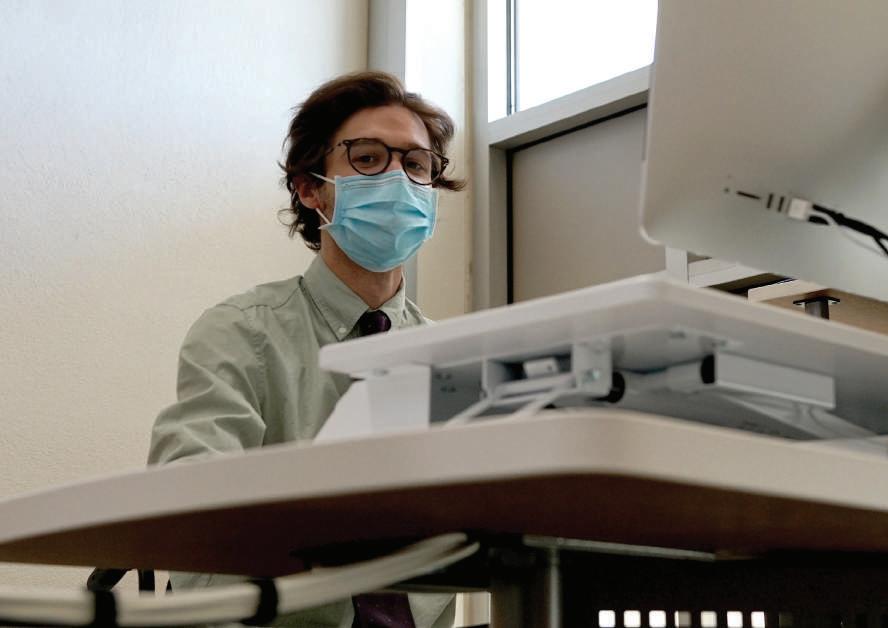

PHOTO BY BEATRICE ALCALA

Professor Nolan Trowe prepares for his “Photo 20” class at a computer station in Da Vinci Hall on April 21, 2022. VAMA is offering the photojournalism class for the first time since the fall semester of 2017.

Advertisement

Photojournalism Makes Comeback

BY BEATRICE ALCALA

Photojournalism returned to the class schedule during the spring semester afer a long break that sent students to Pierce or Valley College to complete the degree requirement.

“Photo 20” has not been ofered at L.A. City College since Fall 2017. Tis semester, Photojournalism Professor Nolan Trowe brings new energy to the class afer its long absence. He meets with photographers on Tuesdays and Tursdays in Da Vinci Hall. Te all-Mac laboratory on the third foor is brand new and bright with a slight sterile feel. Windows line one side of the classroom.

Te Internet reveals a diferent window into Trowe’s work. He favors black and white images. His Instagram page shows a collection of abstract photos from interesting points of view. His portfolio may inspire students as they develop their own style.

“It’s great to hear from the students, and I can spread the knowledge that I have and the dialogue … I really feel like I learn just as much in my class as students are learning from me,” Trowe said.

On a Tursday afernoon, Trowe returned midterm projects to students that included a 1500-word essay, and a photo that students produced. He told photographers that writing is important and helps them compete for scholarships and grants.

Lara Barney is a journalism major, and says she enjoys producing images.

“Professor Trowe has helped me apply my own values to the photos I take of the world,” Barney said.

Christian Chavez is an applied photography major. He says it is important to treat the individual or environment properly. He goes through a process of internal questions and answers as he shoots.

“I am passionate about multiple things in my photos, but recently it’s more about taking my time and properly composing my shots,” he said. “Currently, I am composing a series about the Los Angeles River, and I wish to create an honest perspective from the vantage point of a born and bred Angelino, giving the environment and its inhabitants grace and something worth remembering.”

Louis White is also enrolled in “Photo 20.” He always says he likes to shoot everything. He is a photo editor at the Collegian, the campus newspaper. White is a very active photographer who is always ready for an assignment. He attends many marches, sports and news events.

“I always try to think when shooting,” he said. “In other words, is this image necessary, why should it exist? Te way it has had some efect on my image making is that, I am even more cognizant of the humanity and dignity of an image.”

Photojournalist Delia Rojas gravitates toward the same hard news events. White and Rojas both covered the evictions of the unhoused in Echo Park by the LAPD last spring. Rojas is compelled to shoot the news she sees on city streets.

“Te circles of care have been a great assignment that has helped me come out of my comfort zone, and I’ve been able to go out and explore more with my photography skills,” Rojas said. “I’m really passionate about shooting portraits, and that’s something I decided to focus on for the fnal part of the circle of care because I really like capturing people’s emotions.”

FROM “MARCHERS DAY” PAGE 1 Protest Draws Non-Traditional Workers to DTLA for May Day

says Miguel Lopez, executive treasurer of Teamsters Local 630.

“Today we all came together and have a message that capitalism and power extract all the profts, and do not give anything back,” Lopez said. “Tey don’t even pay taxes, and working people pick up the tab.”

Local street vendors were marching and protesting for better conditions and better treatment from the police. Tey say they are harassed, and the police do not allow them to work on the street. Tey say most of the time, the carts they use to carry their products—which can cost as much as $30,000—are confscated by the police and they receive a ticket and a fne that must be paid in cash.

“It’s an honor to be part of this great and historic march,” said Rosalinda Martinez, who came to support workers and immigrants. “Many people fought and died for workers to have an eight-hour working day.” Martinez says it is a battle against “the corporates,” and the march is an important place to be heard.

“Immigrants are the building block of the wealth of the country,” Martinez said as she shouted, “Si se puede.”

People chanted and danced along the route. It was a big celebration for many of the protesters, as they hoped for an end to the pandemic. A group of strippers joined the march this year.

“We are very happy to be representing our movement and getting visibility for our cause,” said “Velveeta,” a stripper who declined to provide her real name for privacy reasons. Strippers are trying to get unionized with Strippers United, an independent union. “Velveeta” says most of the workforce are immigrants and strippers who provide essential work.

Te March ended at Grand Park in front of City Hall without incident. communities from the East to the West Coast.

“Tey lef as though they were feeing some curse,” the scholar Emmett J. Scott wrote. “Tey were willing to make almost any sacrifce to obtain a railroad ticket, and they lef with the intention of staying.”

Bronzeville sprang from the void created in Little Tokyo when the United States government incarcerated thousands of Japanese American citizens, not long afer Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. Te action forced 125,000 Japanese Americans from their homes.

It became a destination for jazz and nightlife, but a type of blight developed as more and more migrants poured into the area for housing.

In the play “Masao and the Bronze Nightingale,” by Dan Kwong and Ruben F. Guevara, based on Guevara’s short story of the same name, the audience witnesses the lived experiences of three distinct communities: Latinx, African American and Japanese Americans.

Te writers weave the narratives into a bittersweet love letter to Little Tokyo and Bronzeville. Kwong co-directed the play and says the post-war Japanese American experience was so varied and diverse, that it could be the reason Bronzeville is pretty much forgotten.

“Tere was no unifed experience of the community, so it tended to be unspoken, not talked about,” he said. “I think some of the reasons for that are just the way that the history of communities of color is generally ignored. And this is a very complex history; this intertwining and overlapping of African American and Japanese American communities is very complex. It’s not easily explained. It’s not easily described, though we may try.”

POLICE WIRE April, 19 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Student Services Building April, 21 2022 –Assault-Non Aggravated: Hands/Feet/Fist – North Park April, 23 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Student Services Building April, 23 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Student Union, Parking Lot 3 and Parking Lot4 April, 24 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Student Union, Parking Lot 3 and Parking Lot4 COMPILED BY STAFF April, 25 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Student Union, Parking Lot 3 and Parking Lot4 April, 27 2022 –Petty Theft – MLK Library and Sci Tech Building April, 28 2022 –Non Criminal Report/Injury – Cesar Chavez Administration Building

FROM “HISTORY INTERSECTS” PAGE 1

Photo by Daren Mooko, Courtesy Steve Moyer PR

Michael Sasaki (Masao Imoto) and Angela Oliver (Charlene Williams) share a scene in the World Premiere production of “Masao and the Bronze Nightingale,” a play that runs at the Casa 0101 Theater through May 15.

It helps us to understand how pivotal L.A. history is to the remaking of American history. Now, L.A. in the period I have studied anticipates the America we are experiencing at the dawn of the 21st century.

—Professor Scott Kurashige, chair of comparative race and ethnic studies, Texas Christian University

most decorated unit for its size and length of service in the history of the US military.”

Te 442nd joined with the only African American combat unit during WW II, the 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated African American unit. Te 442nd and the 92nd fought together and drove German forces out of Northern Italy.

While Japanese Americans were in internment camps, African Americans who were barred from living in all but a few zip codes in 1940s Los Angeles moved into Little Tokyo as they arrived in waves of the Great Migration from the South. It is the history that intersects and speaks to the same issues, years apart.

From the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941 to the second wave of the Great Migration and the reshaping of an entire community turned Little Tokyo into Bronzeville, the Collegian looked at how World War II events shaped and transformed the city, even when some of the events happened thousands of miles away.

Te history of Bronzeville—which is not discussed much or very wellknown, even by native Angelinos, is the focus of a play which is currently running at CASA 0101 in Boyle Heights through May 15, “Masao and the Bronze Nightingale.”

Executive Director Emmanuel Deleage ofers his own theory as to why much of the local history that led to the existence of Bronzeville is forgotten.

“It highlights the internment of the Japanese,” Deleage said. “Tat’s something that is historically seen as wrong, to incarcerate the Japanese Americans who had nothing to do with bombing Pearl Harbor. Tat is a dark chapter of American history.”

Long before the attack on Pearl Harbor, which was a turning point in America’s involvement in WWII, at home, African Americans in the South were trying to escape Jim Crow. For more than half a century, from 1915 to 1970, the Great Migration incoming migrants reshaped

Scholars Revisit Los Angeles History

Scott Kurashige is the author of “Te Shifing Grounds of Race,” a book that describes the roles of African Americans and Japanese Americans in the political and social struggles of 20th Century L.A. He says most of Los Angeles housing was exclusively white and closed to Japanese Americans in the 1940s.

Over time, Boyle Heights ofered the best housing opportunities for people of color because there were no racial covenants. Many Jewish Angelinos lived there and Kurashige says it was popular because single-family houses could be sold to Mexicans, African Americans and Japanese Americans. Kurashige is the chair of comparative race and ethnic studies at Texas Christian University. He ofers context for the reception of the returning Japanese American internees. Los Angeles was not a multicultural Mecca as it is sometimes perceived today.

“Some leaders in L.A. [would] do anything to prevent the return of Japanese Americans to the city … White politicians and media fgures argued that violent clashes were bound to erupt if Japanese American residents returned to Little Tokyo, now home to 25,000 or more African Americans,” Kurashige said in a lecture at the Japanese National Museum in Los Angeles in 2011. “And to be certain, housing was indeed scarce, during the war for Black residents in L.A. who found themselves routinely excluded from 70 to 95% of the housing stock.”

Niulan Wright studies at NYU, and she is a reporter for the campus newspaper, the Confuence. In an article last November, “From Little Tokyo to Bronzeville and Back Again,” she discussed housing restrictions, restrictive covenants, and the borders of the historic African American and Japanese American communities in L.A.

“Both groups tended to live in the unrestricted Eastside,” she wrote. “In this area lay Little Tokyo, the commercial and social district of the Japanese, and Central Avenue, the Black center for culture and community in Los Angeles. Lying adjacent to each other, the border between these two communities ofen blurred and cross-cultural relations increased. For example, Black and Japanese adolescents were brought together by youth clubs like sports.”

Te experience of Tomas Robinson, an African American teenager who lived on the cultural L.A. border is telling. Te residents who were expelled by Order 9066 were his neighbors because he was a member of the youth groups of the Japanese Christian Church on 20th Street in the Central Avenue area. “When he saw his friends detained at the Santa Anita Racetrack, the teenager gathered food and supplies on a regular basis sneaking them into the makeshif camp for the family and other internees,” Kurashige said. “Such acts of solidarity helped Japanese Americans to carry on through difcult times and carrying with them little doubt how they cemented lifelong relationships such as these. I think we need to continue to recapture these stories.”

Clock Runs Down on Pearl Harbor History

Lou Conter arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii on Feb. 3, 1941 aboard the USS Arizona. He was almost 20. He had reported to the Naval Training Station in San Diego for basic training, two years earlier.

Te Collegian sat down with the 100-year-old veteran in January in Grass Valley, Calif. He is one of the two remaining survivors of the USS Arizona. Te Collegian met with Conter at his home. A born storyteller, Conter has advice for everyone: “Always do your best at all jobs,” he said.

Conter remembers the last time the big guns on the USS Arizona would sound. It was during a night-fring exercise, on Dec. 4, 1941. Te ship was supposed to re-