4 minute read

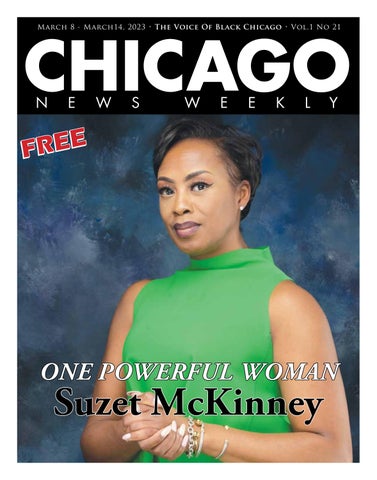

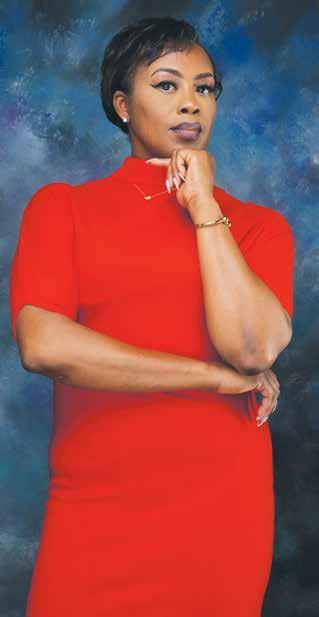

SUZET McKinney One of Chicago’s Most Powerful Women

“Crain’s Chicago Business named you one of 50 Most Powerful Women in Chicago,” how does that happen?

Perfectly poised and professional, Suzet McKinney comfortably begins to spin her backstory. “Well, I think that my career path has been very circuitous and also a bit unconventional.”

Advertisement

Like other brilliant scientific thinkers, Suzet expressed an interest in pursuing a career as a medical doctor. She was an established biology pre-med student, with the intention of going to medical school to be a neonatologist. However, because she attended a school where most of her graduating class was also applying to medical school, she says, “I knew that I needed to do something to differentiate myself from everyone else applying to medical school.”

Serendipitously an internship at Harvard Medical School afforded her the opportunity to learn about public health. As she weighed the pros and cons of choices before her as to how to best distinguish herself, she chose to return to Chicago where she enrolled in a graduate program that awarded her a master’s degree in public health, and coupled with one year of experience in public health, would not only make her a better clinician and help her get into medical school, but also distinguish her from everyone else.”

One month later the anthrax attacks in New York, DC and Florida happened. To her good fortunate she served as the bioterrorism Regional Coordinator for the city of Chicago. Suzet shares, “The 911 anthrax attacks, informed the federal government that the United States was not prepared for another bioterrorism attack,” admits Suzet.

Consequently, Congress appropriated $1 billion to flood into the US public health system and build up the country’s capacity to respond to a bioterrorism attack. Four cities- Chicago, New York, LA, and Washington DC, were determined to be at a higher risk than other places and appropriated additional funding to be utilized to develop and improve their bioterrorism preparedness programs; and if they had none, then they were to initiate one. “So,” Suzet says, “The position that I assumed had not existed. I was the first person in that role at 27-years-old.”

Prior to her position she admits that like most people, she assumed that Bioterrorism was a law enforcement issue. It is not. The weaponization of chemicals and organisms released in open public places makes it a public health issue because terrorist’s incite panic by causing large numbers of people to be infected with an illness and sometimes die. Suzet admits, “I found it fascinating.” Suzet extended her commitment to a second year. The world was facing ‘chemical terrorism,’ talks about nuclear and radiological terrorism and Suzet, found each form of bio-terrorist episode fascinating based on how they affect people’s health and impacted society. Two-years out, and she just couldn’t tear herself away from the work that she was so immersed and had grown to love, to leave for medical school.

She replaced her plan with a new vision and identified that each position that interested her had a doctorate degree in some relevant related area and that’s when, “I realized, that I’d pursue a doctorate degree in public health.”

Suzet says, “When I completed my doctorate, I’d been promoted to the 3rd promotion as a deputy commissioner in the city’s public health department that she began to build a national profile, because that role, put her in a position on par with colleagues in the other four cities.

And anytime the federal government wanted to test something out or needed some advice about something pertaining to her expertise, “In Chicago, I was the goto person. And I started serving on various advisory committees for CDC, for HHS, as well as other federal agencies,” says Suzet, in January of 2009, Suzet, officially became deputy commis-

Continued from 11 sioner and was set to defend her dissertation, graduate and move on that May. She, sat back and took a deep breath and says, “That April, my boss who was the health commissioner for Chicago, informed me, that I was charged with leading the city’s response to any threats because he had to manage the messaging via the media circuit.”

Suzet recalls, “I got a call from DHS in 2010 who had a new upgraded system to detect chemical and biological agents just in the ambient air and they wanted to do a field test in Chicago putting me in the lead position. Being in her presence you sense her composed and collected manner as she says, “I’ll just say that it was a scary time. Because while the threat was the Public Health Department’s responsibility, under my leadership, I knew, that we needed the support of the full public safety community in Chicago. After talking with them about what this would do for us the police chief and the fire chief both said to me, we’re going to support you in this. But if anything goes wrong, it’s your ass on the line, not ours.”

“The four-month testing was successful, and the Feds decided to expand the testing in other big cities when, they realized that I was the only public health person in the entire United States who had led the testing.” SUZet taKeS a DetoUr

“I was asked to move to Washington to serve as a senior adviser to the Department of Homeland Security,” she says. “As Sr. Advisor for Public Health and Preparedness at the Tauri Group, I provided strategic and analytical consulting services to the U.S. (DHS), BioWatch Program.” cHalleNGe

She returned to Chicago and Ebola happened. “That was the thing that was never supposed to happen. As Deputy commissioner she led the public health response to Ebola. In reflection she says, “The State Department and the DHS decided to reroute all travel from West Africa to the United States, to five cities of which Chicago was one.” This forced Suzet to dedicate several members of her team to airport duty to work with the CDC quarantine station. The responsibility was immense. Finally, Ebola ended in 2015. She had survived the challenges and navigated Chicago through the worst of the worst, the thing that was never supposed to happen and she emerged victorious.

“I needed a new challenge” rolled off Suzet’s tongue smoothly succinct. A few months later she was recruited to assume the position of CEO of the Illinois Medical District in the fall of 2015. Suzet, articulates, very mindful of her leadership skills, “My first charge as the new CEO was to execute a complete financial turnaround, financial transformation of the organization, the institution that is the Medical District, that included 560 acres of medical research facilities, labs, a biotech business incubator, universities, raw land development areas, four hospitals and more than 40 healthcare-related facilities located on the near west side. She continues, “Unaware when I accepted the position, that the Medical District is an independent unit of local government just as Chicago is a local government.” So as CEO, she was the mayor. Within two years of leadership, Dr. Suzet McKinney accomplished a finan-

Continued on 14