8 minute read

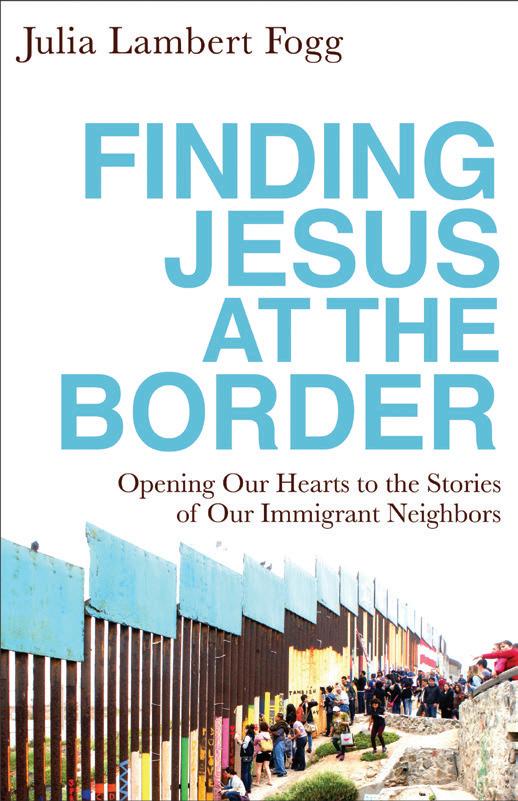

FINDING JESUS AT THE BORDER

CROSSINGS In her new book Finding Jesus at the Border, professor of religion Julia Lambert Fogg tells the stories of people caught up in the U.S. immigration system, putting today’s stories in dialogue with boundary-crossing by Jesus and Paul in the New Testament.

JOHN MOORE/GETTY IMAGES

Advertisement

Central Americans proceed into Mexico on foot after crossing the Guatemalan border in October 2018. The migrant caravan’s movements were sensationalized and viewed as threatening by some U.S. news outlets. Professor Fogg asks, How do stories like this look from the migrants’ side?

These book excerpts are abbreviated, condensed and edited. Names have been changed.

A Crisis of Belonging To hear the border narratives in our Scriptures we must listen to the stories of those who cross borders and those who live at the border of belonging: the immigrants, the undocumented, the asylum seekers, children separated from their families. With this book I invite you to make that effort. I invite you to really listen to your neighbors’ stories, to wrestle with their experiences as undocumented people, and to imagine what it’s like to walk in their shoes, navigating the public school system, the emergency room, a courtroom or an insurance claims office. I invite you to ask what it’s like seeking help from a local congregation instead of giving it, receiving charity rather than making an offering, figuring out the tax system, seeking worker’s disability or understanding tenant rights. Transformation begins here: listening to our neighbors’ stories. Along the way we will meet neighbors we may not have even known we had.

Santiago came across the border from Mexico almost 33 years ago, a baby in his mother’s arms. Her name is Maria, and at that time she was fleeing poverty and the violence of an abusive marriage to seek a better life for herself and for her son. Once she reached California, she settled in an immigrant Mexican community. She remarried. She had another son. She lost her second husband—a U.S. citizen—to military service abroad in Iraq. She moved again. Her boys grew up speaking primarily in English and some Spanish with an American accent. They went to public school, played soccer, attended church and got fairly good grades. There were gangs in the area, but Santiago managed to keep himself and his little brother out of trouble.

Around Santiago’s 15th birthday, everything ground to a halt. He found out he was different from the other kids. He had no legal documents, no birth certificate, no Social Security number, and therefore no legal identity. Everything he had always taken for granted—life in California, his friends, his education, his family, even his being American—fell away. If he wasn’t American like all the other kids, what was he? Who was he? He had no memory of Mexico or his Mexican father. In grade school, Santiago had studied the U.S. government as “our” government. He had learned U.S. history as “our” history, “our” democratic experiment, and “our” land of opportunity, but this American identity was no longer his. He was not part of “us,” and—this was the ultimate betrayal—he never had been. It was all a lie.

4 CLU MAGAZINE Santiago withdrew from his friends, his church, even his brother. Omar, three years younger, had a California birth certificate and baby photos with his American father. Somehow, Omar belonged. Santiago had no one to talk to about his discovery. His mother didn’t understand much English, let alone the future implications of his legal status. Omar had no idea his older brother had been born in a different country or that they had different legal rights. Santiago was terrified someone would discover his secret. What if his mother were arrested and sent back to Mexico? What if the police came and took him too? He couldn’t focus at school. He stayed home or sat in detention for acting out. He failed that year and attended summer remedial classes. The school held him back a grade anyway. He was a ghost, drifting through his life because none of it was truly his.

What Would Jesus’ Family Do? The flight of refugees recurs across the centuries and echoes through the biblical narrative. In every generation, under different empires, God’s people were on the move. In times of political turmoil, famine, and economic hardship, individuals, families and tribes in the ancient Near East—today’s Middle East—sought shelter or grazing lands in Egypt, and, when circumstances changed, they moved north and east, away from Egypt. Following the same migratory patterns both before and after the exodus,

BRIAN STETHEM ’84

Jews settled throughout northern Africa, especially Egypt, along the Mediterranean coast, through the Arabian Peninsula, and across adjacent lands. It is in this context of historical Jewish migrations and life as a religious-ethnic minority under foreign empires that Matthew, a Jew, opens his gospel with a genealogy, a roll call of Jesus’ ancestors who put their faith in God and moved when they were called to move.

Matthew’s story of Jesus’ birth bears a striking resemblance to stories of immigrant children carried across borders in their mothers’ arms today. Consider the choices the holy family had to make before the boy Jesus was even weaned. When Joseph hears of the political threats against his child (Matt. 2:13), he must decide whether to flee with his family or to send Mary and the baby away. Perhaps he should stay in Bethlehem, work, and send money back when he can. But can Mary and the child make the journey to safety alone? The roads are dangerous and it’s best to travel in large groups. Still, a traveling group can sometimes turn on you or take advantage of you while you sleep. You never know whom to trust, where to rest, what to eat. If the family makes it to Alexandria—a journey that could take weeks—they may be able to locate some distant relative in a nearby village. But these are all guesses; nothing is certain except the voice of God telling them to flee. According to Matthew, the danger to their son is real, imminent and terrifying. They must leave quickly.

Consider Mary’s prospects as a refugee in Egypt. As a new wife and mother, she leaves her home, her sisters, cousins, aunts and neighbors—all of the more experienced women who could support her and help her raise her first child. Couldn’t she just go into hiding among them? But what if King Herod’s violence spreads beyond Bethlehem? Herod the Great could be erratic and vicious when he felt threatened. But fleeing all the way to Egypt? Wasn’t Joseph strong and able to provide for his family by working with his hands? With the coming slaughter, the holy family must choose now: follow the divine dreams, flee south and save their boy, or remain where they are and hide from the coming violence. According to Matthew, they follow the divine command and flee.

Safe in His Cell During my first visit to Adelanto Detention Center in Victorville—a federal immigration facility run by the private, for-profit corporation GEO Group—I met a young man, recently arrived, whom I’ll call Jorge. Jorge had lived in a border town in Mexico. His father was a security guard for a local business. He had a younger sister at home. One day Jorge approached the U.S. border guards and asked for asylum. In speaking with me he was circumspect about the details that led him to the decision to turn himself in. But as we spoke I gathered that he had been pressured by local drug lords from a young age. His family could not protect him, and finally the cartel pulled him out of school, forcing him into illicit work. When he could no longer tolerate the cartel, he

turned himself in for protection. He was 16.

The border patrol handed Jorge over to ICE officers who placed him in a juvenile detention center for 15 months. Jorge was OK with that—in juvenile detention he could attend classes with other teens. In quiet Spanish he told me that it “wasn’t great, but it was good. I could study. I was still in the secundaria. I want to study, and I want to graduate. In juvenile detention I studied and worked. They moved us around a lot. Nine months there, six weeks there, three months somewhere else…” On his 18th birthday, ICE moved Jorge to the detention center in Adelanto. A teenager landed in an adult world. Here, among the men, Jorge kept to his cell for safety. I asked him if there was room to exercise. Not really. He told me they were allowed to leave their cell and go out into “the yard.” But, he said, his eyes inching sideways, “it’s crowded out there, and dangerous. In the yard, you have to be careful where you walk. It’s better to stay inside.” His words were chilling. In crowded gathering places like the exercise yard, Jorge was an easy target for men picking fights or recruiting for gangs.

From Jorge I learned that detention centers’ systems and protocols are similar to institutional prisons. Detainees wear color-coded clothes that

communicate whether or not they have a past criminal record, and, if they do, what kind of conviction they served time for. Jorge, like the older men in his cell, wore dark blue scrubs indicating no past criminal record. He could be in the same room with men wearing orange scrubs indicating they had, at some point in their life, committed a nonviolent crime such as a drug offense.

There was a third group of men dressed in red scrubs. The men wearing red had, at one time in their life, been convicted of a more serious or violent crime. Like the men in orange, the men in red were now detained solely on an immigration violation. Even so, men in blue scrubs could not be in the same room as men in red scrubs. With respect to the law, none of the detainees were inmates or serving time. They were all waiting to put their civil case before an immigration judge. Yet they were color-coded and wore their past records on their bodies.

Julia Lambert Fogg’s Finding Jesus at the Border: Opening Our Hearts to the Stories of Our Immigrant Neighbors (2020) is available in paperback and e-book editions from Baker Publishing and booksellers. Content used with permission www.bakerpublishinggroup.com.