10 minute read

THE MAGIC OF 750CC

Words: Martin Lambert. Photos: Kawasaki Motors Europe The magic

of 750cc

ver since the first pioneers swung a leg over what were basically motor-bicycles, a cycle with an engine crudely inserted into the tubular frame, the maxim “bigger is better” has applied to the passion for powered two wheelers. And as the biking boom transferred from British control to the Japanese an “order” was establishing itself with “capacity classes” being created such as 125cc, 250cc, 500cc and 650cc.

At the “tipping point” in the early 1970’s with the dying embers of the UK industry fading and bikers experienced a tidal wave of product from the land of the Rising Sun, the three quarter litre class broadened and burst onto the scene. Taking over from the Norton Commando and Triumph Tridents of the UK and Italy’s Guzzi V7’s plus Laverda SF’s of the 70’s from that day to this the 750cc capacity has signified a gateway to the most extreme performance, the doorstep of the litre class.

Over the years Kawasaki has made many 750cc machines; Club Magazine now looks back at some of the many highs… and a few “not so highs” on a journey down motorcycling memory lane. Here is Part One of a Two Part insight.

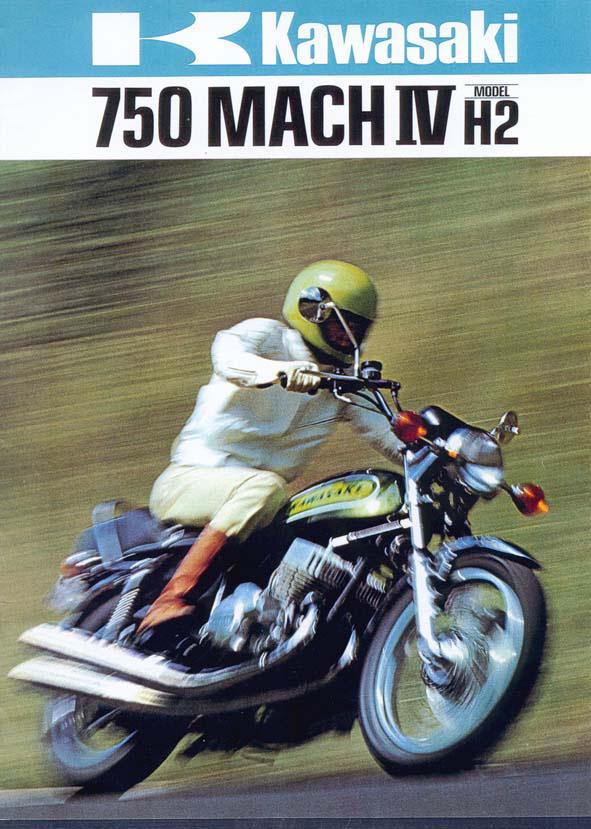

H2 Mach IV The Steroid Superbike

For many, 1972 was a definitive was cheap and wages high so the $999 year for Kawasaki. The brochure for the original stock H1 was similarly of the time ran the headline “The kept in line and “scaled up” the same year of the Tri-Stars” for this was with a retail price tag of just $1395 the season that Kawasaki unleashed for a machine that Kawasaki’s official the legendary 750cc H2 Mach IV. drag racer, Tony Nicosia, took through Alongside the diminutive 350cc S2 the timing lights at 11.95sec from a and the updated, disc braked H1 500 standing start over the quarter mile in B form, the H2 was the third at the AHRA Spring Nationals in 1972 triple in the range and lived up on machine chassis number #00012 to the hype of being the “bigger, which Kawasaki USA later gifted to badder brother” of the H1. him. There was no change in the Lasting just four iterations over four 1968 design philosophy of the model years, the legend that was already established H1 500, no the H2 evaporated in a haze of two “softening” of stance; the H2 stroke smoke, killed off by the world was basically a scaled up oil crisis in the 1970’s and the new H1, a Mach III on steroids. “eco lobby” in the USA driving down Capacity was up, carb exhaust emissions. Between the Mach sizes were up, power was IV and final H2C power dropped from up and speed was up. In 74bhp to closer to 70 and refinement the USA main market gas crept in, even the tendency to wheelie

under acceleration in the lower gears was significantly “tuned out” with something like a 2 inch longer swinging arm. No matter, the H2 was – and still is- one of Kawasaki’s (and the biking world’s) definitive 750cc machines with a legacy that reaches to current times and its ultra-performance namesake, the Supercharged Ninja H2, being deliberately named after the 70’s icon.

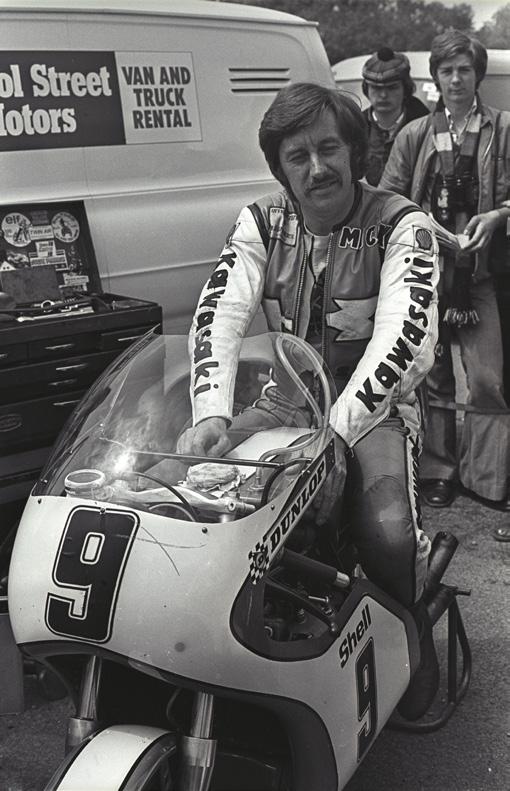

Above: Mick Grant astride a KR750 at Mallory Park

H2R / KR750 Fearsome Flexi-Flyers “It was not long before the limits of the air-cooled very much road based H2R were reached and the KR750 was developed”

Streetbike prowess in the 1970’s possessed no subtleties such as reed howl of the H2R’s of racing legends was almost exclusively built on valves to control induction and the like Yvon Duhamel, Gregg Hansford racing success. For sure Japanese days of the electronically operated and Barry Ditchburn captivated the manufacturers saw racing as a very exhaust valve were a figment of race going public as riders pushed direct route to take on and beat rivals someone’s future vision. Those first tyres to their adhesive limits and to establish performance credentials “Green Meanies” were just three big engines to as close to seizure as as well as create brand reputation. carburettors, three big pistons and possible in the fight for podium “Win on Sunday and sell on Monday” acres of inlet, transfer and exhaust supremacy. characterised the 1970’s both on dirt port area. In fact there was so little It was not long before the limits of and asphalt with Kawasaki adapting cylinder area that some ports were the air-cooled very much road based street bikes for racing duties with “bridged” with metal to stop the H2R were reached and the KR750 notable success. For the triples this piston rings, and presumably pistons, was developed. Still sharing some philosophy first created the H1R 500 disappearing like Alice’s white rabbit architecture with the street machine, racer then, as the 750cc road bike was down a dirty great hole. the KR750 possessed a waterrolled out, the H2R three quarter litre No matter that the frames of these cooled single piece cylinder block, racers. “flexi-flyers” were as crude as the magnesium crankcases, an air-cooled

Using the same basic crankcase contemporary suspension and tyres, clutch plus the benefit of a few years and gearbox construction as the road when they were “on song” in an trial and error in chassis technology. bike, the simple piston ported racers admittedly narrow power band, the Tyres were coming along too and

Below: Gregg Hansford on the KR750

tyre life across a race was more predictable; so much so that the KR750 in the hands of Mick Grant won the most arduous race in the world in 1977, the Isle of Man Senior TT. Braking the timing beams on the section between the Creg and Brandish at an incredible 191mph on his way to a race average of 112.77mph over six laps each of 37 ¾ miles. In reality this was more of a swansong for the mighty KR as other manufacturers had launched four cylinder two-stroke racers but no one can deny that the sight of Mick Grant and Barry Ditchburn in the cut and thrust of domestic racing in the 1970’s was the beginning of many a young UK spectator’s obsession with Kawasaki. Z750 Twin Balanced yet Bland

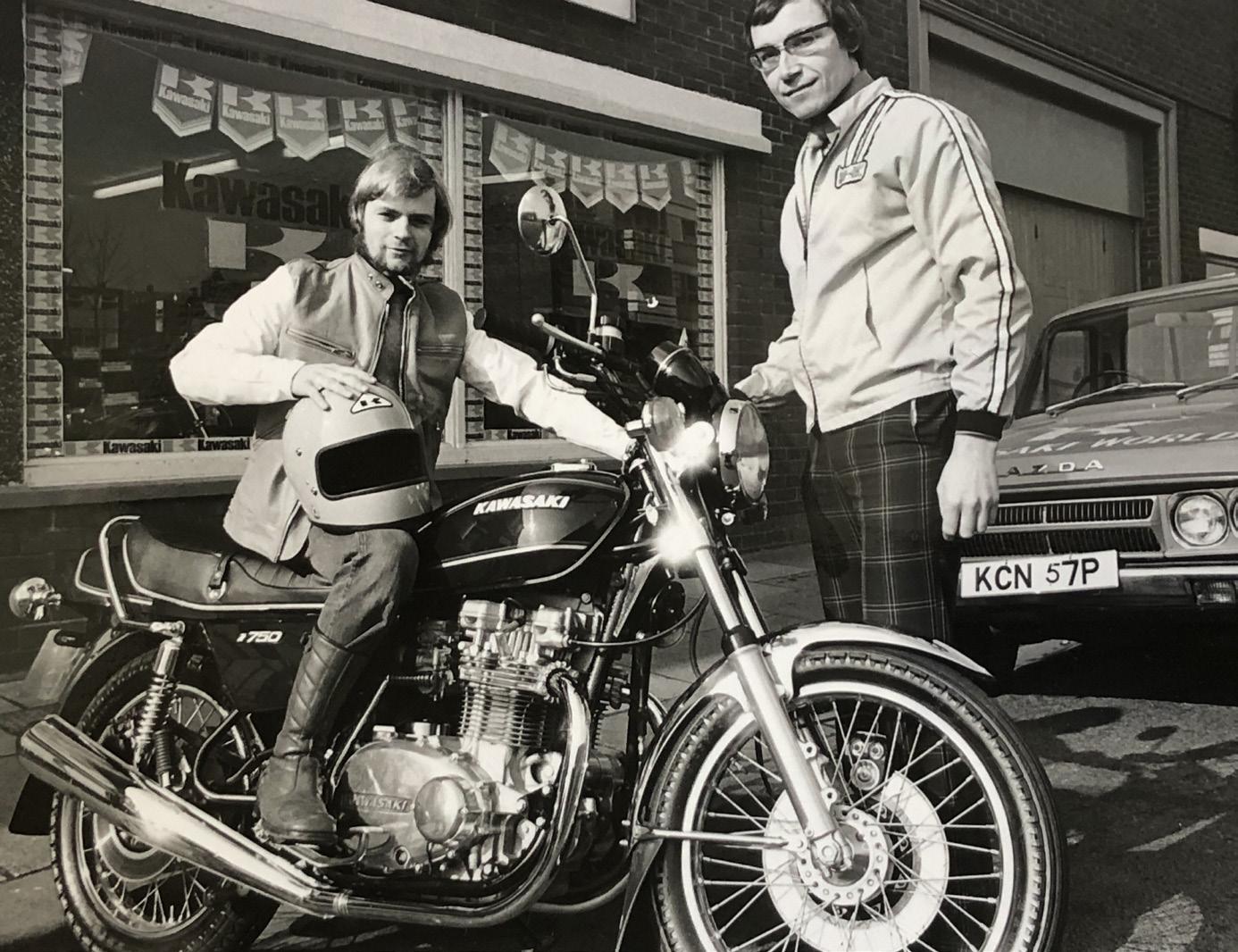

Then – seemingly as suddenly as aimed at an older generation of rider; the 1970’s had started with a perhaps even the rider who harked wild-eyed optimism, the later part after what maybe the British industry of the decade in motorcycling terms would have created had it survived. was something of a wake-up call. Benefitting from what appeared to Manufacturers were chasing buyers be the world’s largest side panels with yet more diverse products. and a seat that never really looked They sought pockets of sales not like it was meant for the machine, the yet realised while producing such Z750 was a sort of “bigger brother”, wide model lines that “internal to the already introduced Z400 twin competition” was a very real threat and sat in a weirdly zig-zagging to sales expansion; add to that global range with a 400cc twin then the trends toward cleaner running Z650 four, a Z750 twin and the new vehicles and the inevitable call for Z1000-A1 four. safer, more responsible road use Perhaps it was a case of product and the exit of the banzai H2 Mach IV in 1975 was replaced “the Z750 twin diversity, or trying to assuage the legislators, with what could only be never really hit but the Z750 twin never described as the “worthy and interesting” Z750. A very sociable twin cylinder air-cooled four the mark with buyers despite being offered really hit the mark with buyers despite being offered with alloy wheels, as an LTD custom machine stroke replaced the antiwith alloy or in one of 12 eventual social two-stroke triple wheels” guises. Only recently has offering double overhead the “replacement for the camshafts, no less than two engine H2” found a new, loyal following balancers, a comprehensive blow-by amongst the current crop of hipster gas recycling system and disc brakes shed bike custom builders who value front and rear. Compared to the its outward simplicity and inward styling of the H2, the Z750 was more technology over the more archaic upright, more “mature” and certainly British donor bikes in the field.

The Z750 twin: the answer to a question no-one asked

GPz750 air-cooled Age of the Red Zeds

The somewhat unfulfilled promise of the 1970’s made way for a new rush towards technology in the 1980’s. This was the age of such innovations mobile phones, the CD, mass use of micro-processors and widespread CNC machining technology in manufacture. R&D was suddenly accelerated by an explosion in computing power and the worldwide economy was trying to keep pace with de-regulated stock markets. People had disposable income again and wanted to spend.

Kawasaki’s answer? - “The Red Revolution”, a new approach to bike branding creating a new, distinctive look and feel for a range of machines quite apart from the long established – and for some quite staid – Z range which, to be fair, had debuted the latest air-cooled 750 in the guise of the Z750L bearing the bluff, unapologetic slab sided styling so redolent of the age – a far cry from its beloved and almost Rubenesque Z650 forebear.

GPz evoked performance, technology and style. It eschewed Kawasaki’s lime green heritage, gave no care for the fact that other manufacturers had claimed the colour and

presented a range of bright pillar box red machines that, in the UK, took the market by storm. Not only did Kawasaki become number one in the market thanks to GPz but the market share for the smallest of the “big four” was significantly over 20%, for sure something to cause shockwaves in Hamamatsu and Iwata.

In truth – and aside from some snazzy meter panels with asymmetric speedometers and rev counters plus partial LED displays - the initial GPz bikes in a range of capacities were simply a distillation of what Kawasaki engineers had gathered over many years of making two valves per cylinder, air-cooled performance motorcycles.

Higher lift and longer duration camshafts, better gas flow technology and the possibility to mass-produce to incredible tolerances thanks to the latest raft of computer controlled lathes and milling machines aligned itself to Kawasaki’s burgeoning reputation for appreciating the value of chassis, brake and suspension technology.

The first GPz 750 machines were almost “Red Zeds” with twin rear shock absorbers, bikini cowls redolent of the ground breaking Z1R and 1980’s “essentials” such as acres of “black chrome”.

Transitioning to Uni-Trak rear suspension, the design of the GPz750 became more “rangy” with the rider in more of a racing stance and the bikes in what can only be described as a very fulsome range spiralling in capacity all the way to 1100cc.

While the Z750 of 1977 can best be described as never fulfilling its promise, the GPz 750 in both twin shock and Uni-Trak guise should be considered as unjustly overlooked. The GPz550 was quite simply a rocket ship in terms of performance per cc while the range topping GPz1100 had the benefit of category crushing power and speed. A shame as the further refinement of the air-cooled Z650 engine unit to create the GPz750 bestowed upon it all the attributes of a genuinely accomplished sporting all-rounder that is still sought after by enthusiasts to this day.

But the enemy was within and pretty soon the Kawasaki water-cooled dam would burst consuming the aircooled GPz and many others. For the H2o iterations, one last hurrah for the air-cooled 750cc generation and a further focus on the many three quarter litre Kawasaki motorcycles in a long, rich manufacturing history, we will keep our powder dry for the following issue and part two of “The magic of 750cc”. n