2 minute read

FROM FELIS CATUS TO XENOPUS LAEVIS: STILL LIFES AND XENOBOTS

The earliest paintings that can be considered “still lifes” go back to the fifteenth century BCE, in Egypt, although they were actually funerary decorations and not still lifes in the modern sense of the term. The most famous of them comes from the socalled Tomb of Menna and depicts a group of inanimate objects as a sort of collection of vignettes from everyday life.

Canonically, any arrangement of inanimate objects is considered a “still life.” The notion of “arrangement” is central: that is, the composition, or the way the objects are depicted within the space delimited by the picture frame. Occasionally, among these inanimate objects and as part of the evolution of the genre a living thing may also be depicted. But to be clear: in many still lifes, living things were depicted, yet they were not represented as such, but rather as hunting trophies or food. What was new, then, was the depiction of a living being while still alive.

Advertisement

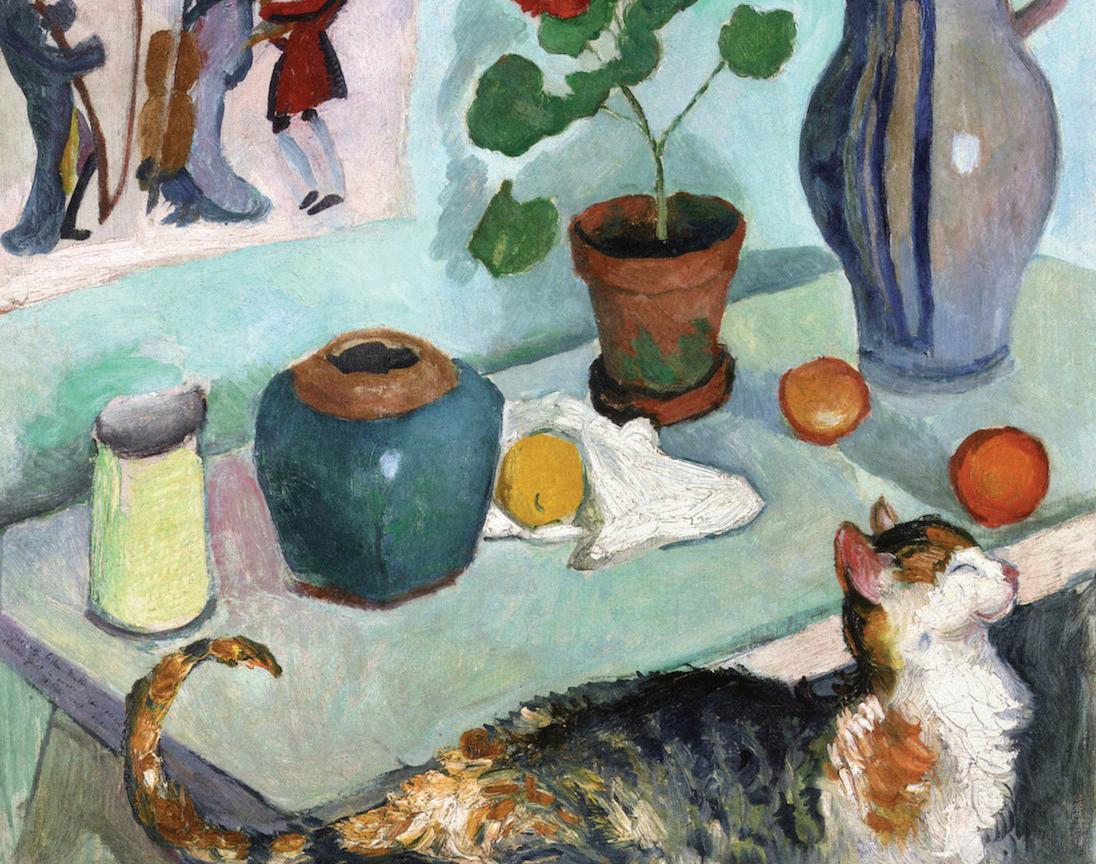

Such is the case of The Spirit of the House: Still Life with Cat, by the German painter August Macke (1867-1914). An outstanding member of the avant-garde movement Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), Macke included a frolicsome little cat in his painting. The idea was supposedly not his own, but came from his mother, who saw the painting when it was presumably finished and commented that it “lacked life” (a slightly peculiar observation in the case of a still life). In order to remedy the situation, Macke decided to include not just one life but nine lives (as we say in English), or at least seven (as they say in German and Spanish). In this way, the still life was finally completed in 1910. The cat contributed the portion of life summed in the metaphor of the title: the “spirit of the house.”

And as Macke’s mother would say, we can always affirm that “life” is lacking somewhere. Why not take it into account? Not the seven or nine lives of the cat, perhaps, but… could there be life in a robot? In a study performed at the University of Vermont, xenobots have been considered “a completely new form of life.” The name of the xenobot comes just as in the case of Macke’s painting from the inclusion of a living being: the African clawed frog, or Xenopus laevis. It is thanks to the stem cells of this spirited African frog that we now have what Joshua Bongard, a researcher at the University of Vermont, has called “novel living machines.” A beautiful way in which science and art continue to amaze us, acting on the frontiers of human knowledge, at the limits between zones still to be redefined, through a combination of research and imagination.

• Original title: Der Geist des Hauses: Stilleben mit Katze • Museum: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (Germany) • Technique: Oil (69 x 74 cm.) Ángel Ortuño

Ángel Ortuño

He has published just over a dozen books of verses in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Spain. His poems have been translated into French, English and German. His most recent book is entitled “ Gas lacrimógeno y otras cosas que no son poemas” (University of Guanajuato, 2018)