4 minute read

James Lovelock’s One Hundred Years

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Tim Cuff/Alamy.

by Dolores Garnica

Advertisement

James Lovelock’s temperature varies —according to the American Medical Association— between 36.5 and 37.2 degrees Celsius. The cells of the English scientist, meteorologist, writer, inventor, atmospheric chemist, and environmentalist, who recently turned one hundred, continue to regulate his temperature in spite of his surroundings and the time of day, his age and his ailments, his level of stress and other factors that may raise or lower the degrees of body heat that keep him alive.

The fact that cells maintain his temperature, as they do for all of us, seems miraculous to many, even as it constitutes a given to his doctors, a challenge for manufacturers of pharmaceuticals, and an inspiration for the recipient of the Wollaston Medal in 2006 for having, according to the citation, “opened up a whole new field of Earth science study.” Lovelock is the ideologue of the Gaia hypothesis, which proposes, in broad terms, that our planet regulates its own temperature by means of its cells, just as our bodies do, a fact that entails significant changes in how we define, observe, and study the earth. As he wrote in The Ages of Gaia (1988): “If we see the world as a superorganism of which we are a part —not the owner, nor the tenant; not even a passenger— we could have a long time

ahead of us and our species might survive…”

For Lovelock, this self- regulation would explain the vast climatic changes we are undergoing and, although it augurs still worse ones for the future, it suggests, far from certain pessimistic, apocalyptic theories, that it is precisely through the study of this planetary cellular self-defense mechanism that the care of the earth might be ensured. According to Lovelock (The Ages of Gaia), “the self-regulation of climate and chemical composition is a process that emerges from the tightly coupled evolution of rocks, air, and ocean —in addition to that of organisms. Such interlocking self-regulation, while rarely optimal —consider the cold and hot places of the earth, the wet and the dry— nevertheless keeps the Earth a fit place for life.” Precisely. For Lovelock, the planet regulates itself in order to preserve the

life existing on it, and that is perhaps the most controversial feature of a theory used, for example, to buttress the idea of a god that created human life and seeks to preserve it, or the existence of an energy that cares for the planet. Theories such as these, formulated outside of the scientific limits within which Lovelock works, show how influential his hypothesis has been since the 1970s, when it brought the issue of a planetary environmental crisis to the forefront.

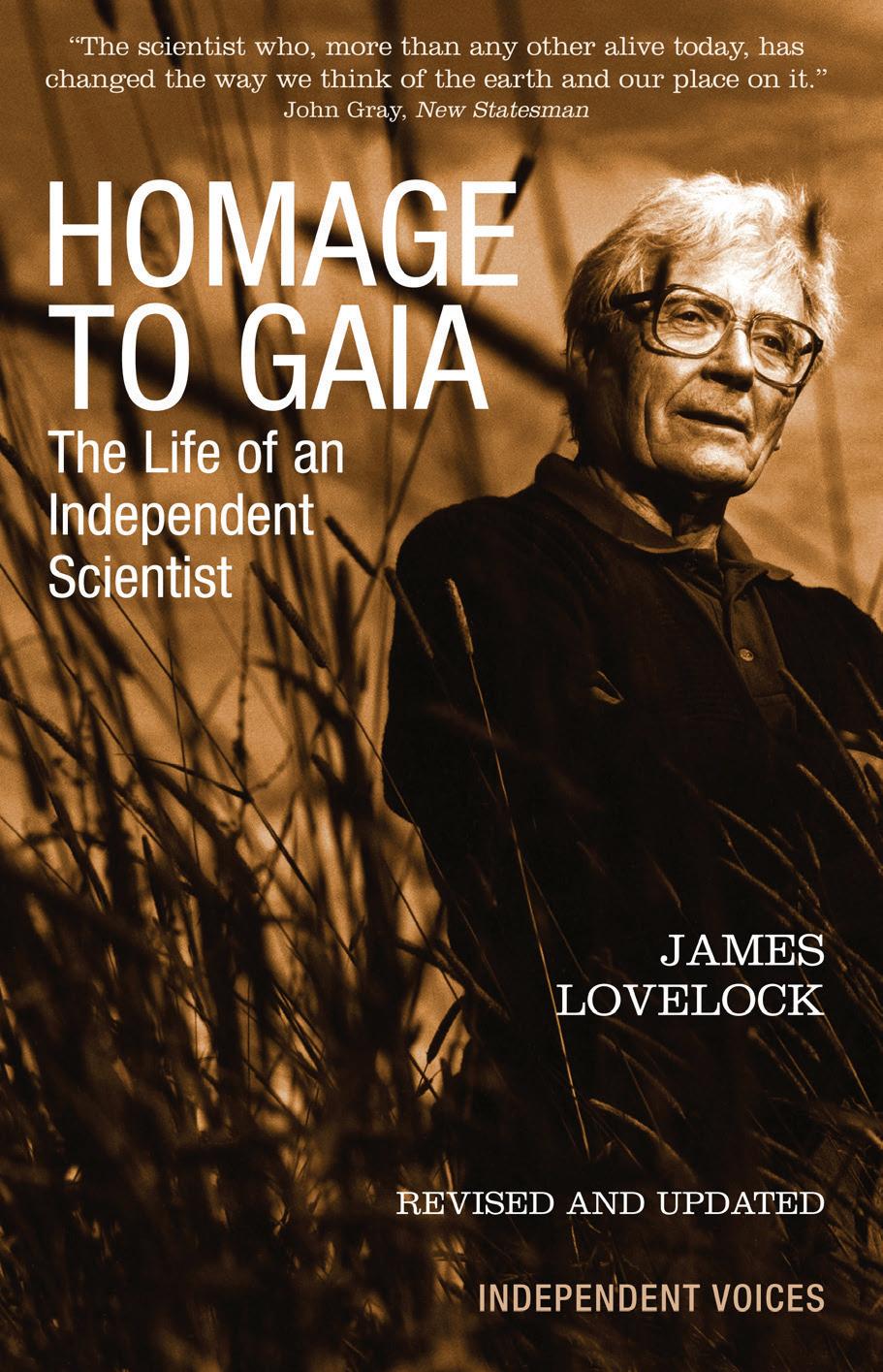

The story of the Gaia hypothesis began with one of the inventions considered a key to the twentieth-century ecologist narrative, also created by James Lovelock (a Commander of the Order of the British Empire since 1990): the electron capture detector, the use of which led to the discovery of the distribution of pesticide residues in the environment, one of

An electron-capture detector (ECD) for a gas chromatograph, invented by James Lovelock. Science Museum London.

the inspirations for the book Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, known as the founder of the environmentalist movement, whose temperature was also regulated by her cells until her death in 1964.

The detector was so important to science that Lovelock, who was working at the time for NASA in the United States, had to surrender the patent, along with many of the results of the climate studies that led him to formulate his hypothesis. “I suspect the Earth behaves like a gigantic living being,” he told his friend and neighbor William Golding, whose cells were also maintaining his body temperature, and who suggested the name Gaia to Lovelock in the late 1960s. In 1979 Lovelock published Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, followed by The Ages of Gaia in 1988 and The Revenge of Gaia in 2006, in addition to many other books and more than two hundred articles.

Ninety years ago, James Lovelock’s father gave him a kit for performing household electrical experiments, stimulating an interest in scientific work that has earned him eight honorary degrees, though no Nobel Prize. Currently Hon- orary Visiting Fellow at Green Templeton College, Oxford, but still an independent researcher, at one hundred, James Lovelock still has a great deal of work to do, as reflected in his optimism about nuclear energy, not as an armament, but as a contribution to the reduction of fossil fuels. As he explained in an interview: “There have been seven disasters since humans came on the earth, very similar to the one that’s just about to happen. I think these events keep sepa- rating the wheat from the chaff. And eventually we’ll have a human on the planet that really does understand it and can live with it properly. That’s the source of my optimism.” Lovelock’s wise cells continue to regulate his temperature.