8 minute read

Harrisburg and the Underground Railroad

by Jacob Clagg

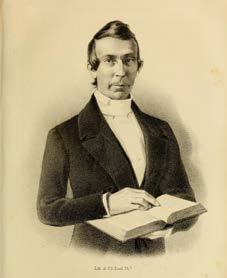

It just so happens that while the instrumental people, institutions, and networks of the Underground Railroad were being put in place, the Churches of God was also being established. The Churches of God’s creation was entirely a reformist movement by John Winebrenner and those who supported him, but we cannot miss the significance of the CGGC’s historical penchant for social involvement, or put another way, for how Winebrenner believed the Churches of God ought to play a part in societal reform as well as religious reform.

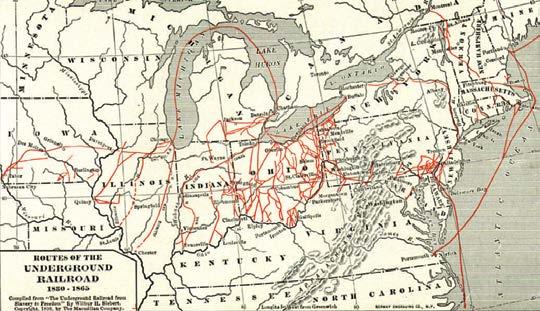

A number of our earliest churches (and many which still stand today) run up and down the Cumberland Valley. This valley is shaped by the North and South Mountains which bend and snake across four states: Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Towns like Hagerstown, Chambersburg, Shippensburg, and Carlisle were natural stops along the road, and all lead up to or away from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s capital. Harrisburg was built upon the Susquehanna River, a natural transport highway, and likewise, by the end of the 1830s, the city was connected by a railroad to the rest of the country. By the 1850s, Harrisburg had become a hub for rail traffic, and would become a nexus of Union supplies during the Civil War. A freedom seeking slave from the South might reasonably pass by a number of these towns in hopes of making it to Harrisburg, and eventually taking road, rail, or river to any number of locations, like Philadelphia to the East, Pittsburgh to the West, or Canada to the North. It was common knowledge that if one made it past Harrisburg, they would effectively be untraceable, and therefore safe from slave catchers.

Despite this corridor’s prevalence, anthropologists and historians have known for a long time that stories of the Underground Railroad are just as likely to be unverifiable folklore as they are legitimate historical facts. The “holy grail” of any historian interested in the Underground Railroad then is to find verifiable evidence that a physical location was used to harbor, hide, or help freedom seeking slaves. One account from the History of the Salem United Church of Christ, previously the Salem Reformed Church that John Winebrenner served at, tells an oral history of the church cellar, through which “fleeing black slaves were warmed, clothed, fed, and sent on their way.”1 Just after this though, the authors put the story in doubt, saying that the church, largely of GermanSwiss descent, was unlikely to have taken a position on the issue of slavery. The difficulty of evaluating the veracity of oral story telling is put on display.

There are multiple reasons why strong evidence is so difficult to come by. The most significant reason is the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required law enforcement in all states to aid in the capture of runaway “fugitive” slaves, and which made it a punishable offense for free civilians to aid these “fugitives.” Accusations made under the Act required no evidence besides the testimony of the prosecution, and “fugitives” were unable to speak in their own defense, resulting in a kangaroo court given that commissioners tasked with carrying out the arrests made twice as much from guilty verdicts as non-guilty ones.

On the other hand, the Fugitive Slave Act also galvanized abolitionist societies. The Act was met with much uproar, particularly in Northern states, who reacted by creating or doubling down on Anti-Slavery societies, publishing papers, tracts, and other materials, and, occasionally, civil disobedience. One famous story from Harrisburg in 1851 resulted in the unfortunate capture of three black men who were accused of being runaway slaves. The three men were subjected to a complicated trial and became the center of a riot outside of the Harrisburg jail. Free black and white abolitionists came together and went toe to toe with a smaller group of southern slavers. One of the defendants escaped in the scuffle but the other two were re-arrested, along with many of the rioters. Anti-slavery individuals signed a petition pleading for the two black men to be released and freed, the names of those individuals are still available, and some of which were part of the Salem United Church of Christ, Winebrenner’s first pastorate. Unfortunately, the petition went unheard, and the two black men were unjustly taken to Virginia.

The lamentable Act did have a couple of additional unfortunate impacts. As Todd Mealy points out, “The many stories that were kept in personal diaries were destroyed after 1850 for fear of that law.”2 Likewise, it was this law that drove so many helpers of the freedom seekers truly underground in the first place. The result is that much of the evidence for antislavery activity does not come in the shape of secret tunnels, but in public facing activism. If we accept the idea that the Underground Railroad was as much about public support for freeing slaves as it was providing the means of escape, as Todd Mealy suggests, then John Winebrenner’s own contribution to the Underground Railroad is obvious.

John Winebrenner was a founding member of the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society (HAS) in 1836, which made it their object to see slaves “instantly to be set free and brought under the protection of the law.”3 Likewise, the HAS was not interested in compensation to slave owners for the freeing of their slaves, and instead desired to see the compensation given to the “outraged and guiltless slaves, and not those who have plundered and abused them.”4 At time of signing, these were contentious positions to take, even among abolitionists, who were likely to hold a spectrum of beliefs about the best way to abolish slavery without collapsing society writ large. Winebrenner continued to be active with the group, and simultaneously began a long printing campaign, using the The Gospel Publisher (a previous name of this very periodical) to consistently report on local, national, and international concerns about slavery, news about slave legislature, biblical understandings of slavery, the church’s stance on slavery, and featured other abolitionist thinkers, and occasionally stories of slaves, including injustices perpetrated on black men and women. Winebrenner’s publications loudly, and sometimes contentiously, published the church’s stance on abolitionism, in one issue saying, “It is the imperative duty of every minister of Christ and all Christians to bear their testimony against this sin [slavery], and to use all righteous means in their power for its total extinction.” This was a resolution passed by the Eldership in 1845.

The Gospel Publisher’s anti-slavery rhetoric was noticed far beyond the borders of Pennsylvania when in Charleston, South Carolina, riots broke out from the increasing frustration of pro-slave southerners who were fed up with the amount of abolitionist tracts that were making their way south. One quote from the Charleston Courier reads that the rioters, “seized the bags containing abolition tracts and made a public bonfire the whole last evening.” Apparently, The Gospel Publisher was among the burned tracts.

Despite the controversy, Winebrenner never saw the abolition of slavery as a necessary pretext to war and despised the idea of civil wars in general. Sectarianism in general was an anathema for Winebrenner and his stance on Anti-Slavery was to hold slave owners close, in the hopes of changing their hearts and minds about the issue, particularly if they were of Christian conviction already. Like most people, it seems unlikely then that Winebrenner would have broken the laws of the time to bring about his Anti-Slavery desires. Instead, Winebrenner worked within the confines of the law, doing all he was legally able to do to bring about an end to slavery. Unfortunately, John Winebrenner never lived to see the full fruits of his labors in this area, having passed away on the eve of the American Civil War. Yet, Winebrenner’s legacy is one that stands alongside staunch Black and White abolitionists who endeavored to create the Underground Railroad.

1 A History: Salem United Church of Christ (German Reformed) Harrisburg, Pennsylvania from 1787 to 1988, by Joseph J. Kelley, Eleanor E. Kelly.

2 Biography of an Antislavery City: Antislavery Advocates, Abolitionists, and Underground Railroad Activists in Harrisburg, PA, Publish America, Baltimore by Todd Mealy, 2007, Pg. 104

3 Proceedings of the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society, pg 3.

4 Ibid.