10 minute read

RH Factors' 50-Year Legacy

RH Factors' 50-Year Legacy

by Rhea Hirshman

If you walk into Remsen Arena, take a few steps, and turn around, you will see a wall festooned with banners featuring the seven Choate Rosemary Hall graduates who went on to garner Olympic medals in women’s ice hockey. “Every time we step on the ice,” says current head coach Laura Troy, “those banners remind us of the heritage of this team.”

But the program that has sent alumnae to every Olympics since women’s ice hockey made its debut in the 1998 games in Nagano, Japan, began almost by accident.

As Susan (Susy) Peck Lauderdale ’75 recalls, the idea for a girls ice hockey team emerged among members of the Rosemary Hall ski team on a bus ride to the Mt. Southington ski area during her fifth form year. The weather was miserable. The slopes were icy. “And,” she says, “we hated that bus ride. We all wanted to do something else in the winter, but no one was interested in basketball or volleyball or gymnastics.” Then, Lauderdale says, someone called out “Let’s start a hockey team! Can we play hockey?!”

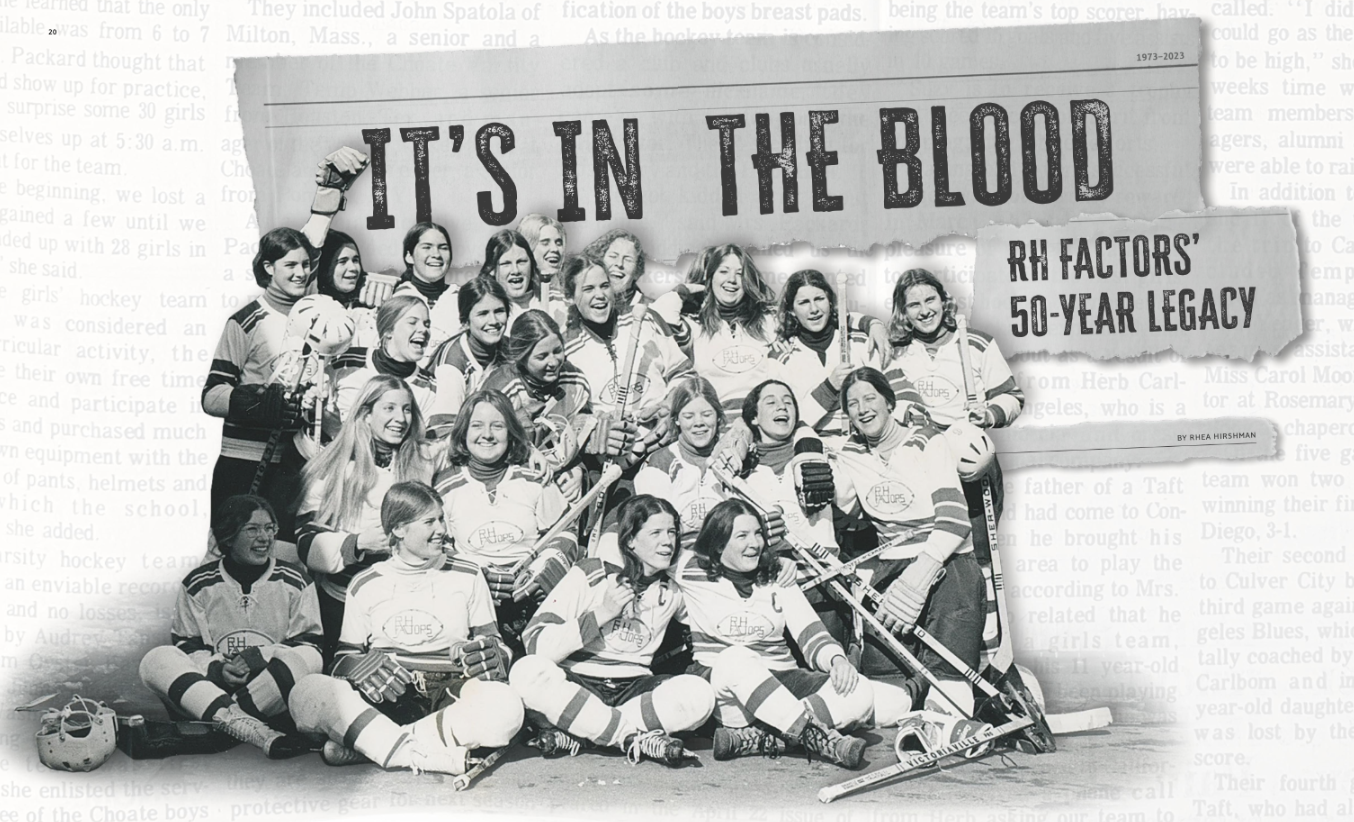

A group of students got Polly Packard (wife of sixth form dean Jeremy Packard) on board as the coach and, by December 1973, a girls ice hockey club was practicing. Calling themselves the “RH Factors” (“We’re out for blood”), they played their first interscholastic game the following January, an away game against Taft, which has since become a perennial rival. The Factors’ 5-4 win included a hat trick (three goals by one player in the same game) scored by Lauderdale, who finished the season as the team’s top scorer and remembers the moment well. “I was just coming out of the penalty box,” she says. “Taft didn’t see me. A defender was about to take a slap shot and I came in right behind her and stole the puck.” The Factors’ fans went wild. The Factors finished their first season, topped off with a trip to the first East-West Invitational Girls Hockey Tournament in California, with an undefeated regular-season record.

Because so few secondary schools had girls teams at that time, the RH Factors often played against college teams such as Middlebury, Yale, and Wesleyan. Opposing teams were not the sole challenge in those early days. The only available ice time began at 5:30 or 6:00 a.m. The girls had to provide most of their own equipment, although The Choate School athletic director Bill Pudvah ’34 was able to scrape together a few items such as helmets, pants, and socks. Rather than hockey skates, which are lighter, more maneuverable, and more protective, the players wore figure skates. Still, 28 players completed that first season, and by the following year, girls ice hockey was considered an official winter sport.

As was often the case for the RH Factors, many of the girls who wanted to play had little or no experience with hockey. Cheryl Stahl Borek ’80 had spent her childhood skating on frozen ponds with a stick in her hand, wearing too-big skates handed down from her father. “We didn’t have the kind of depth that teams have now,” she says. “Many of my friends were like I was — just learning the game.” She was cut from the squad in her first year. But she learned to play under the club program run by Bill Pudvah and made the varsity squad, coached by Ted Sherman, the following year. Her father bought her good-fitting skates. By her sixth form year, Borek was the team captain and was recruited to play at Brown.

“I loved my entire time at Choate,” Borek says, “in the classroom and on the ice. A lot of my identity was wrapped up in being a female athlete, especially in a sport that was not widespread at that time. Being in that early wave gave me confidence in other parts of my life.” While the male hockey players were supportive, and the coaches treated the girls like serious athletes, Borek also remembers significant discrepancies in the resources and facilities allotted to the girls’ team.

The team remained the RH Factors for a year or so after Borek graduated. By the 1982-1983 season, they had become the Choate Rosemary Hall girls ice hockey team and were wearing jerseys emblazoned with “Choate.” Facilities and resources continued to improve, although Kristin (Moomaw) Harder, who coached the team from 1991 to 2000, says that even as late as when she started,

I had to battle to be sure that the players were treated with respect — that they got equal access to ice time as the boys, that their uniforms were appropriate, and that they had the same access to transportation. I wanted them to be recognized for their hard work and talents, and to have every opportunity to develop as individual athletes while creating the most competitive team possible.

In a growing program, recruiting became a significant part of the coaches’ job. As more younger girls gained access to the sport through leagues, camps, and schools, coaches were traveling extensively to watch players, meet with families when they came to the Admission office, and develop relationships with youth and club coaches around and outside the area. Troy notes that the coaching staff’s objective is to recruit and support student-athletes who value both their athletic and academic commitments. “Part of our job is to help them find that balance while also preparing them for their college experiences,” she says. “In both academics and athletics, students are responsible for their own performance but can learn from each other and work collaboratively. We don’t want our players to sacrifice academics to competitive hockey or vice versa.”

For the past several years, ice time, facilities, and other resources have been equal for the girls and boys hockey teams. Recruiting efforts have brought in athletes already skilled in the game, including the seven Olympians: Angela Ruggiero ’98, Kim Insalaco ’99, Julie Chu ’01, Hilary Knight ’07, Josephine Pucci ’08, Phoebe Staenz ’13, and Sammy Kolowrat ’15.

James Stanley, who teaches history and economics, has been an assistant coach with the program for many of his 23 years at the school. “When I think about girls hockey here,” he says,

I recognize that ours has been a pioneering program. Our players have helped show other young women around the country what they could do. There is self-knowledge that comes with sports. In competition, players learn that they can push beyond their ideas of their own limits — and see that they can accomplish more in all aspects of their lives than they previously realized.

Stanley remembers his first time seeing Angela Ruggiero in action — when she was a third former playing against a very good team from the school where he was then working. “I thought, this is something different,” he says. “This is taking the game to a whole new level.”

Recruited by a Choate coach who saw her playing at a summer hockey camp in Connecticut, California native Angela Ruggiero had played hockey since she was seven. Winner of four Olympic medals, including the gold in 1998 while she was still a high school student, she is the recipient of many other accolades and awards in her college (Harvard) and professional careers, including induction into the United States and international hockey halls of fame.

An author, business owner, and sought-after public speaker, Ruggiero gave the 2012 commencement address at Choate. Still, she says, as someone from a blue-collar, working-class family, coming to Choate Rosemary Hall for her was not primarily for sports but for the academics. “Choate changed my life,” she says. “It was the nurturing environment I needed, especially being all the way across the country on my own. I knew that I was getting the chance of a lifetime academically. My experience at Choate was about developing as a person, learning how to study, and helping me find confidence. It flipped a switch in my head about how I saw myself and what I could accomplish.”

Kim Insalaco, Ruggiero’s teammate on Team U.S.A. in 2006, a first-generation college student who came to Choate as a fifth former, says of the 1998 Olympics team: “It put Choate girls ice hockey on the map, and the visibility of that event was incredibly powerful,” she says. “It showed me that I could get to the pinnacle of the sport I loved. Choate helped me get there.” She credits her teachers and coaches — particularly Kristin Harder — with helping her “form into the person I wanted to be.”

One year behind Ruggiero, Insalaco set out to break her friend’s single-season scoring record. When she did so, with 51 goals in her sixth form year, Kristin Harder commented, “Well, it looks like we are headed in the right direction!” Insalaco went on to play hockey at Brown, where she sometimes found herself on the ice opposing Ruggiero and Julie Chu, who also went to Harvard — “not easy playing against them, but fun and rewarding,” she says.

Four-time Olympian Chu grew up playing basketball, hockey, and soccer. While sports helped her feel a sense of community as she adjusted to boarding school life, she also relished the full range of academic offerings, and experiences such as checking out the School’s improv scene and watching her peers perform in plays and concerts. When she entered Harvard after deferring admission for a year so she could train for and compete at the 2002 Olympics, she says, “The foundation I had built at Choate helped me take full advantage of the college student-athlete experience.”

After Harvard, Chu played professionally. She has received many honors, including being chosen to carry the American flag during the closing ceremony of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, and having the national rookie of the year award named for her. Now a full-time coach at Concordia University in Montreal, Chu sits on the National Hockey League’s Player Inclusion Coalition, a group of current and former NHL players and women’s professional hockey players “who work to advance equality and inclusion in the sport of hockey on and off the ice.”

Harder, who traveled to the Olympics three times to cheer on the players she had coached, says, “It was amazing to have a front row seat as so many barriers were broken for women in the sport — first Olympics, first gold medal, a professional women’s league, Hall of Fame Honors for female players — none of which existed when I started coaching at Choate.”

Lauderdale adds,

Who knew that a few restless ski team members and several other determined young women would be willing to buck traditional gender roles and do whatever it took to create the team that they wanted? I think I speak for everyone who participated in the Factors’ creation — the players and all who supported and taught us — to say that we are so proud of everyone who has made the program what it is today. We hope that you all had as much fun as we did because we had a blast!