6 minute read

Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics – To take or not to take?

Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics – To take or not to take?

By: Mi Kyung Lee, BSc (Nutrition and Food Sc), GradDip (HSc), MA, PhD

Advertisement

The term ‘probiotic’ means “for life” in Greek. It is currently used to describe bacteria which are associated with beneficial effects for humans and animals. The original observation of the positive role played by some selected bacteria is attributed to Elie Metchnikoff, a Russian scientist, who worked at the Pasteur Institute at the turn of the century. He is best known for his pioneering research in immunology and was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

At the same time, a French paediatrician, Henry Tissier, observed that children with diarrhoea had in their stools a low number of bacteria (bifida) which were found to be abundant in healthy children.

Probiotics are defined as ‘live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host, when administered (in a viable form and) in adequate amounts’ (FAO/WHO, 2002).

The FAO/WHO Working Group specified the following key aspects of this definition for food use (FAO/WHO, 2002):

• Taxonomy (strain identification): A probiotic must be a taxonomically defined microbe or combination of microbes (genus, species and strain level)

• Safety: a probiotic must be safe for its intended use

• Substantiation/Scientific evidence of health benefits: A probiotic must have undergone controlled evaluation to document health benefits in the target host

• A probiotic must be alive when administered Prebiotics are defined as ‘non-digestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacterial species already established in the colon, and thus in effect improve host health’ (Gibson and Roberfroid, 1995 – cited in (FAO/WHO, 2006).

Synbiotics are defined as products that contain both probiotics and prebiotics (Zhang, Ju, & Zuo, 2018).

Probiotics have been consumed by humans since time immemorial, for example as fermented milks, yogurts and kimchi. Breastmilk is an example of a synbiotic as it contains living bacteria (bifidobacter, lactobacillus) and prebiotics (oligosaccharides). This is one of the reasons why breastmilk is so superior to the artificial formula.

Use of Probiotics in preventing or treating illness/conditions

Recent systematic reviews have reported the following beneficial use of probiotics:

• Prevention and treatment of Paediatric diarrhea (Guarino, Guandalini, & Lo Vecchio, 2015)

• Treatment of Infant colic (Schreck Bird, Gregory, Jalloh, & Risoldi Cochrane, 2017)

• Prevention of Antibiotic induced diarrhea both in children and adults and moderately reducing the duration of diarrhea (Guo, Goldenberg, Humphrey, El Dib, & Johnston, 2019)

• Improvement in Abdominal pain, especially in children categorized as having irritable bowel syndrome (Mellis, 2017)

• Prevention of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in adults (Barker, Duster, Valentine, & Hess, 2017)

Not conclusive

• Prevention of traveller’s diary (McFarland & Goh, 2019);

• Influence of gut bacteria on the brain: Therapeutic potential for depression, anxiety, autism and other psychological disorders (Butler, Cryan, & Dinan, 2019).

Use of Probiotics in otherwise Healthy People

It is currently not clear if the regular intake of probiotics, as a supplement, has any long term benefit. The FAO/WHO Working Group stated that the use of probiotics should not replace a nutritious diet and a healthy and active lifestyle in otherwise healthy people. There are inherent biological difficulties in the administration of probiotics. The gastrointestinal tract develops its microbiome early in life and by two years age immunological tolerance has developed for the 1000 or so types of bacteria living in a healthy gut. After that time the introduction of new bacteria is usually unsuccessful and to have any effect probiotics have to be given daily or even more often. Thus, the use of probiotics likely confers more temporary than long-term effects, and so if long term benefits are identified, continued intake would be required.

Food Sources of Probiotics

The most common bacteria included in commercial foods or added in dietary supplements or drugs are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Food sources of probiotics (live organisms) include yogurt and some fermented food and drinks.

Not all fermented foods can be considered as probiotics, but they can have health benefits (Chilton, Burton, & Reid, 2015). Eating fermented foods could increase the number of microbes in the diet by multiple folds. Food processing, including pasteurization, destroys microbes eliminating any probiotic function. The most abundant microbe in kimchi (fermented cabbages consumed in Korea) and sauerkraut is Lactobacillus plantarum. As a Korean-born Australian, I am happy to see kimchi on the list of beneficial food for gut health. However, one caution of the fermented products is that they are usually high in sodium content, especially when consumed in a large quantity. Consuming sodium reduced fermented probiotic-rich products as part of a regular diet would be the best outcome.

Probiotic Supplements and Regulation

Is there a regulation of probiotics used as supplements? A recent review of the current regulation of probiotics used for the dietary management of medical conditions concludes that the current regulation of probiotics is inadequate to protect consumers and doctors (de Simone, 2019). Overall probiotic use is safe in most of the cases. However, probiotic use should be avoided in some people who are immunologically compromised.

Generally randomised controlled trials of probiotics have been disappointing. Probiotic containing foods are associated with health benefits in longitudinal studies. When probiotic bacteria are isolated and given for preventive and therapeutic purposes the results are mostly disappointed with few positive Cochrane reviews. This is similar to many other individual nutrients confirming that a healthy, balanced diet is likely to be the best treatment(Binns, Lee, & Lee, 2018).

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) recommends to review the following four criteria before choosing a probiotic:

1. “Probiotic strain: Not all the probiotics are the same. Match the particular strain with published scientific research.

2. Proof of efficacy: Probiotics must be tested and be shown effective in humans to determine health benefits. Look for information such as scientific evidence and what health claims on the products mean.

1. Quality and quantity: Choose a quality product at the right quantity. Probiotics can be effective at varying strengths. Scientific studies have determined health benefits from 50 million to more than 1 trillion CFUs (colony forming units, which is the measure of viable microbes in a probiotic) per day. A probiotic with higher CFUs doesn’t necessarily equal better quality or effectiveness.

2. Package information: Pick quality packaging and a trusted manufacturer” (ISAPP, 2016)

Key messages:

• Gut microbiota may influence many areas of human health from innate immunity to appetite and energy metabolism, but in most areas conclusive proof is not yet available.

• Diet (and different components of food) and medication have a strong influence on gut microbiota composition

• Eat healthy diet (e.g. Mediterranean diet, DASH diet) rich in fresh fruit, vegetables, fish, less meat and less fast food

• include fibre rich food in the diet (whole grains, fruit and vegetables, etc.)

• Include fermented products in your diet e.g. yoghurt, kimchi, sour kraut, etc.

• Probiotic supplements – it is not worth taking unless you have gastro-intestinal problems where therapeutic benefit has been established.

Conclusion

Probiotics may be beneficial to health, however, even more important are the dietary factors that help maintain a diverse and healthy microbiome. Instead of looking for one component in food to boost health, eating healthy diet (and healthy dietary pattern), being physically active and leading health-conducive lifestyle should be emphasized for the prevention of lifestyle associated non-communicable diseases.

Useful Resources

• Gut Microbiota for Health (Public Information Service from European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility): https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/ en/home/

• A consumer’s guide for probiotics: 10 golden rules for a correct use: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.07.011

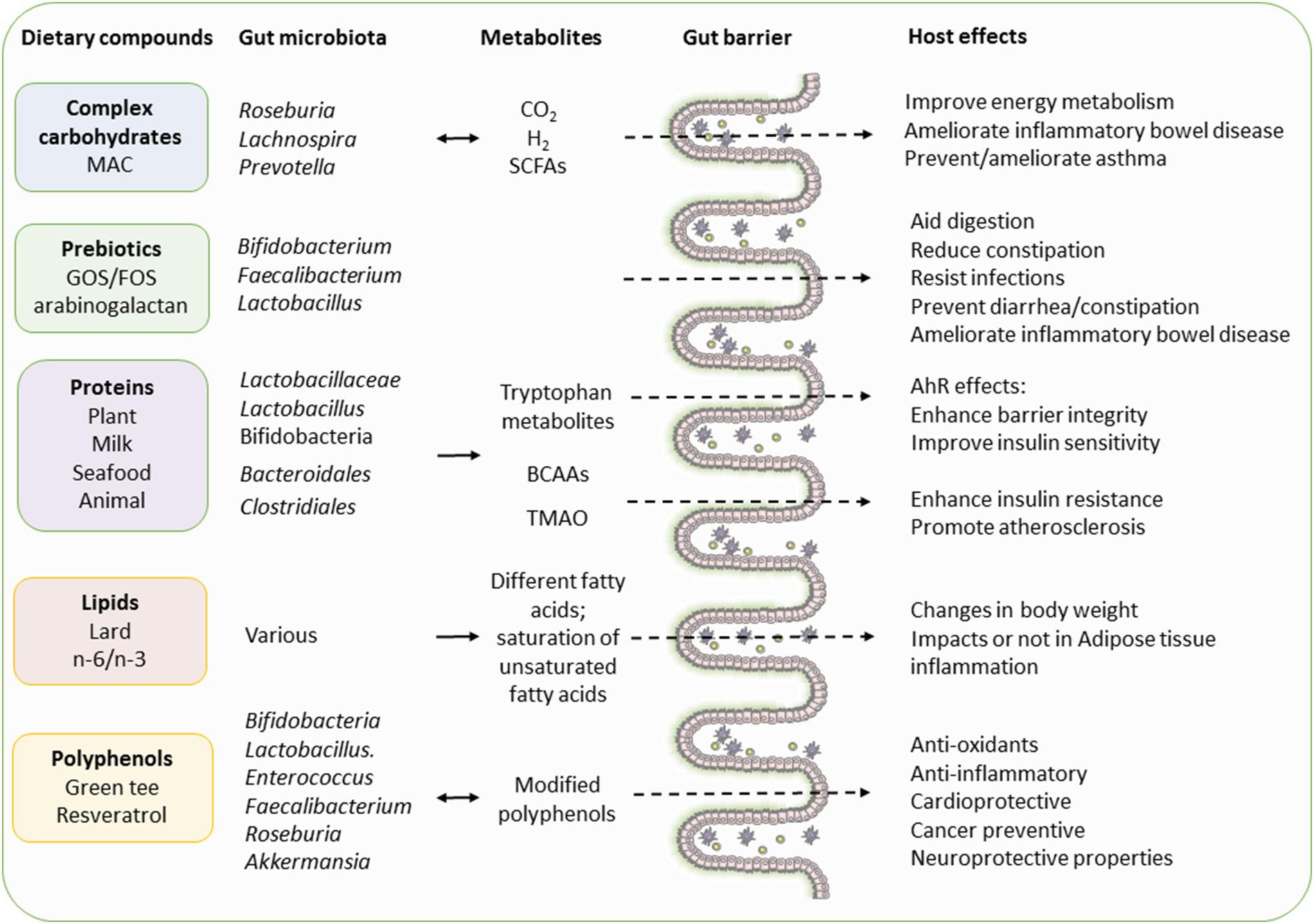

Fig. 1. Overview of the interplay between food components, gut microbiota, metabolites, and host health. Dietary compounds may elicit changes in the composition and the activity of the gut microbiota resulting in the generation of secondary metabolites that modulate host responses. Arrows indicate interaction between gut microbiota and metabolites. Ahr: Aryl: aryl hydrocarbon receptor; BCAAs: branched-chain amino acids; MAC: microbiota accessible carbohydrates; SCFAs: shortchain fatty acids; TMAO: trimethylamine oxide.

REFERENCES:

1. Barker, A. K., Duster, M., Valentine, S., & Hess, T. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of probiotics for Clostridium difficile infection in adults (PICO). Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 72(11), 3177-3180. doi:10.1093/jac/dkx254

2. Binns, C. W., Lee, M. K., & Lee, A. H. (2018). Problems and Prospects: Public Health Regulation of Dietary Supplements. Annu Rev Public Health, 39, 403-420. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013638

3. Butler, M. I., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2019). Man and the Microbiome: A New Theory of Everything? Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), null. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095432

4. Chilton, S. N., Burton, J. P., & Reid, G. (2015). Inclusion of Fermented Foods in Food Guides around the World. Nutrients, 7(1), 390-404.

5. Danneskiold-Samsøe, N. B., Dias de Freitas Queiroz Barros, H., Santos, R., Bicas, J. L., Cazarin, C. B. B., Madsen, L., . . . Maróstica Júnior, M. R. (2019). Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Research International, 115, 23-31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.043

6. de Simone, C. (2019). The Unregulated Probiotic Market. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(5), 809-817. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.018

7. FAO/WHO. (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Retrieved from London, Ontrario, Canada: https://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/ en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf

8. FAO/WHO. (2006). Probiotics in Food: Health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. Retrieved from Rome: http://www.fao.org/tempref/docrep/ fao/009/a0512e/a0512e00.pdf

9. Guarino, A., Guandalini, S., & Lo Vecchio, A. (2015). Probiotics for Prevention and Treatment of Diarrhea. Journal of clinical gastroenterology, 49, S37-S45. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000349

10. Guo, Q., Goldenberg, J. Z., Humphrey, C., El Dib, R., & Johnston, B. C. (2019). Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic‐associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004827.pub5

11. ISAPP. (2016, 2015). Probiotics: Consumer guide for making smart choices Retrieved from https://isappscience.org/clinicians/consumer-guidelines-probiotic-2/

12. McFarland, L. V., & Goh, S. (2019). Are probiotics and prebiotics effective in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis, 27, 11-19. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.09.007

13. Mellis, C. (2017). Probiotics for recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Journal of paediatrics and child health, 53(7), 722-723. doi:10.1111/jpc.13623

14. Schreck Bird, A., Gregory, P. J., Jalloh, M. A., & Risoldi Cochrane, Z. (2017). Probiotics for the Treatment of Infantile Colic: A Systematic Review. Journal of pharmacy practice, 30(3), 366-374. doi:10.1177/0897190016634516

15. Zhang, N., Ju, Z., & Zuo, T. (2018). Time for food: The impact of diet on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrition, 51-52, 80-85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nut.2017.12.005