11 minute read

CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S 2021 BEST

UP FOR GRABS

While the top (Texas, Florida) and the bottom (just guess) of our annual rankings remain unchanged, what has changed are the stakes, with a growing number of CEOs we polled open to a post-Covid change of locale. Governors, take note. BY CHIEF EXECUTIVE STAFF

Advertisement

DESPITE A GLOBAL PANDEMIC, near-economic collapse, civic unrest, just-plain-insane election cycle and everything in between during this crazy Covid year, when it comes to the places CEOs like to do business, the old saw is true: The more things change, the more they stay the same.

For the 17th year in a row, Texas tops Chief Executive’s Best and Worst States for Business list. Number two? Florida, once again. When it comes to the three criteria CEOs tell us they value most in site selection—tax policy (37 percent rank it first), regulatory climate (35 percent) and talent availability (25 percent)—Texas and Florida outclass all comers.

And once again—yawn—California, New York, Illinois and Massachusetts pile up at the bottom of our rankings (based entirely on polling of the nation’s CEOs) where they have dwelt for most of the list’s existence.

But while the names at the top and the bottom remain unchanged, what has changed— dramatically—are the stakes. Governors take note: Our survey—of 383 CEOs in March 2021— finds the nation’s business leaders an increasingly restless bunch thanks to Covid. They’re open to all kinds of new ideas about how—and, more to the point—where to do business.

Forty-four percent of those we surveyed report that they’re “more open than before to examining new locations” for their business, while 34 percent said they’re “considering shifting [or] opening significant operations [or] facilities in a new state.” In a world of remote work, reshuffled markets and flat-out rethinking of nearly every aspect of business, the hearts and minds of CEOs are very much up for grabs.

RANKING 2021 BEST & WORST STATES FOR BUSINESS

<<LOSS FROM 2020 RANK GAIN FROM 2020>>

Texas 1 Florida 2 Sun, fun—and open. Florida had winning optics in a dismal year. Tennessee 3 North Carolina 4 Indiana 5 South Carolina 6 Ohio 7 While Texas suffered a Nevada 8 serious setback when its Georgia 9 electricity grid failed during Arizona 10 a freakishly bitter winter Utah 11 storm in February, the state managed to hang onto its top 12 South Dakota spot again (see story, p. 51). Virginia 13 Delaware 14 Michigan 15 Wyoming 16 Iowa 17 Missouri 18 Louisiana 19 Colorado 20 Idaho 21 Wisconsin 22 Kentucky 23 Governor Kristi Noem’s defiant New Hampshire 24 stance on allowing businesses Montana 25 to carry on during Covid Oklahoma was absolutely not okay in 2021, as Nebraska Kansas 26 27 propelled national headlines— and a big jump in CEOs’ rankings. plunging global oil Oklahoma 28 prices devoured North Dakota 29 the state’s Alabama 30 economy, a Arkansas 31 boom-bust cycle other energy Mississippi 32 states have Alaska 33 learned to hedge West Virginia 34 over the past 20 New Mexico 35 years. Maine 36 Rhode Island 37 Maryland 38 Vermont 39 Minnesota 40 Pennsylvania 41 Hawaii 42 Connecticut 43 Oregon 44 A strong, pragmatic Covid Massachusetts 45 showing by rookie Gov. Washington 46 Ned Lamont impressed New Jersey 47 CEOs—and pulled tiny Connecticut out of the Illinois 48 basement this year. At the bottom? The usual bunch. Despite New York 49 powerful human capital, high costs remain a turnoff. California 50

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12

NEW DIGITAL FACTORY TOWNS

CODERS AND SOCIAL-MEDIA MAVENS are a dime a dozen in long-established high-tech outposts like Silicon Valley. But to leverage AI in manufacturing, tap into “design thinking” in product digitization and harness big data in actuarial software, companies are looking to places like Chicago, Grand Rapids and Columbus.

The capital of Ohio is employing a “legacy digitization strategy” built around the critical mass of insurance companies headquartered in Columbus, Cleveland and other Ohio cities. The long-time presence of marquee insurers like Nationwide, SafeAuto and Progressive has built a huge stockpile of industry expertise.

“You can find actuaries and people who understand the category here, and it’s a favorable state regulatory environment,” says Mark Kvamme, co-founder of Drive Capital, a Columbus-based VC firm that funded local startups like car insurer Root; moved a travel-insurance startup called Battleface to Columbus from Washington, D.C.; and launched Medicaid-insurance startup Circulo locally.

States and cities making headway with a new strategy: assisting industries and vertical niches where they’ve already dominated—or think they can grab an edge. The playbook is gathering steam thanks to the dispersion of work—and talent—during Covid.

Alex Frommeyer, CEO of Beam Dental, calls Columbus “a goldilocks city for our business. It’s got a huge concentration of digital talent across product engineering, data science, marketing and a bunch of other fields, a university concentration in insurance and the business infrastructure. But it’s not such a ‘discovered’ city where we need to compete with Facebook, Google or Tesla for talent.”

In Michigan, digitization of legacy industries “plays to our strengths,” says Tom Kelly, CEO of Automation Alley, a public-private partnership north of Detroit. The group recently granted 300 3D printers to small manufacturers in two counties, which will then be connected to form a huge additive-manufacturing network.

Based in Grand Rapids, the Seamless Consortium combines about two dozen big local employers that depend heavily on industrial design to finance “proof of concept” engagement with startups around the world related to manufacturing technologies. “It’s easier for physical companies to integrate this stuff than for digital people to integrate all the capital in the physical world,” says Mike Morin, co-director of the group. “That’s why you’re seeing this happen here.”

The city’s history as a “design capital” helps, says Nevan Hanumara, a professor at MIT. “It’s in the DNA and in a network of professionals who hop from company to company there and stay tightly interconnected.”

A Tale of Two Besties

Florida certainly got the memo. From high-profile headhunting for high-net worth Wall Streeters to Governor Ron DeSantis’s flaunting of open beaches—and open businesses—throughout the pandemic, the Sunshine State is the clear winner in last year’s economic perception derby. Jonathan Chariff, CEO of South Motors Group, says Florida’s response to the pandemic has been “a

tremendous factor,” in his decision to expand there—some $40 million in new BMW and Honda dealerships in Miami. “Florida is blowing up. Except for the extra traffic, it’s great.”

And while Orlando’s tourism economy is just starting to rebound, the city that Mickey built is now a true comer against traditional tech outposts. Major homegrown digital companies such as Luminar, maker of lidar for autonomous vehicles, and Fattmerchant, a competitor to Square in digital payments, “have created a lot of new millionaires in Central Florida,” says Tim Giuliani, head of the Orlando Economic Partnership. The area was pursuing as many new-business leads in the first quarter of 2021 as it had in the comparable period of 2019.

“Sunshine, low taxes, Covid openness: What talent wouldn’t want to move there?” says Kathy Mussio, partner with Atlas Insight development consultants in Washington, D.C. “You can save enough in taxes compared with the Northeast to make a down payment on a house in Florida.”

Brand Texas has had a different kind of year. Despite its No. 1 ranking, the Lone-Star State suffered a serious reputational setback when its electricity grid failed during a February cold snap (see sidebar). While rival Florida broadcast-

WHAT MESS IN TEXAS?

TO ALL BUT THE MOST HARDCORE FAN, the scene in Texas isn’t pretty right now. The freak midFebruary winter storm and collapse of its power system delivered a haymaker and wobbled the Lone Star State in the opinion of CEOs across the country for the first time since the 1980s.

Texas’s dominant oil-and-gas business busted on cue, as Covid stalled the global economy— and kept millions of drivers off the roads for months. America’s growing immigration problem is massing mainly at Mexico’s border with the state. And for the first time, key outposts such as Austin are showing signs of growth fatigue. Things got so bad in February that even Texas superbooster Elon Musk seemed a bit grumpy on Twitter with his new home state.

Any other place would be worried about losing its longstanding billing as The Best State for Business. But Texas? Hell, no.

“These things aren’t going to affect our standing at all,” Governor Greg Abbott tells Chief Executive. “People know one-off events occur, and what matters most is what our response is. Texas is responding very aggressively and strongly and will ensure a stable power-grid system that will be the most robust in the United States,” especially after the state legislature finishes grappling with solutions in May.

In fact, Abbott says, despite the failure of wind power in Texas’s numbing outage, by next year the state will be No. 1 in generation of solar as well as wind energy. “That will help keep us the top energy state,” he says, “and much of the transformation is being led by some traditional energy companies that are transforming their portfolios, knowing that fossil fuels will be required for years to come—but also alternatives.”

As for the problem of illegal immigration, Abbott insists it “ebbs and flows” over the decades and “is something that affects the entire nation. Congress and the administration hopefully will be looking for solutions.”

Glenn Hamer, president and CEO of the Texas Association of Business, sums up the everboosterish mood at the top: “Mother Nature can humble any country or state,” he says, “but the fundamentals of the Texas economy are as strong as ever.”

So far, so right. Blackout or not, Texas outscored every other locale in the nation again this year in our annual CEO poll. But after the travails of 2020, among many business leaders—both in the state and outside—there is an emerging realism that low taxes and high confidence alone won’t cut it going forward. “There’s going to be a painful adjustment for a number of years because of the pain inflicted on businesses and homeowners” by Texas’s failure during the storm, says Calvin Butler, CEO of Exelon Utilities, a major conventional power generator in Texas that sustained a pretax loss of as much as $700 million amid the chaos.

The state’s phenomenal growth is beginning to yield some strains. These are most apparent in Austin, where tech companies are flocking from California and elsewhere in search of capable digital workers in a fertile business climate. Among the effects have been skyrocketing real-estate costs and big new encampments of homeless.

“A lot of native Texans have had enough,” says Steve Murphy, CEO of Epicor Software, who relocated to Austin from San Mateo, California, three years ago. “The price of housing in Austin has pretty close to doubled in the last five years. The commutes have gotten bad, and when people go back to the office, they will be worse.” How much worse? Time will tell.

Tech companies are flocking to Austin from California and elsewhere in search of capable digital workers in a fertile business climate.

ed sun, sand and surf, Texas emitted pure misery, images of frozen residents standing in lines for clean water amid one of the largest public infrastructure collapses in the nation’s history—one critics say was largely predictable and preventable.

CEOs noticed. Texans “are saying this is a blip they can fix,” says Josh Brumberger, CEO of Utilidata, a utility-software outfit based in Providence, Rhode Island. “But they should be leading with, ‘This was a colossal failure, and we own it, and here are the things we’re doing to fix it.’”

The Covid Factor

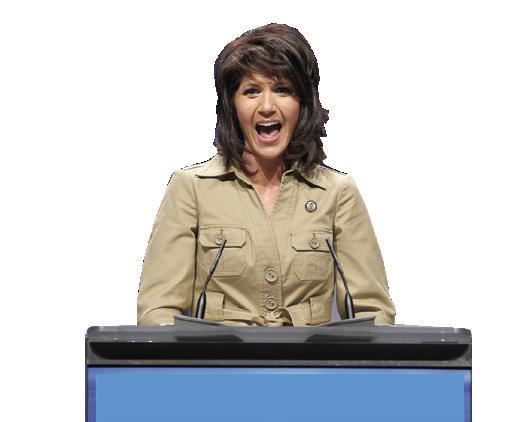

A few states that prioritized remaining open during the pandemic were able to realize a significant bump in this year’s ranking. South Dakota, where Governor Kristi Noem was defiant about allowing businesses in her state to carry on, jumped 12 spots to No. 12 thanks to national headlines—and praise from business leaders. “We’ve been free to operate as we choose, not just through the pandemic, but long before as well,” says Travas Uthe, CEO of Trav’s Outfitter, a big-box outerwear store in Watertown, South Dakota.

Rhode Island, which maintained a more open attitude than its neighbors, climbed to No. 37 from No. 40. “We never shut down our manufacturing sector or construction activities, which was rare among the states, because we partnered quickly with industry on safety protocols,” says Stefan Pryor, Rhode Island’s commerce secretary.

Some expect the bump from strong pro-business leadership during Covid to last. “We won’t know for a couple of years for sure,” says Larry Gigerich, managing director of the Ginovus economic-development consultancy in Fishers, Indiana. “But states that had strong and balanced leadership during Covid will probably be the best positioned for short- and longterm economic growth.”

The virus may finally be easing, but a huge new wildcard in the economic-development game could be how states and cities spend the funds they’ve been promised under the Biden Administration’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package. Port Huron, Michigan, may refund all 2020 property taxes with its $19 million windfall, for instance. Westchester County, New York, plans to use its $187 million to nip and tuck its economic platform via everything from expanding broadband capabilities for remote work to aiding small businesses.

“We’re well-positioned to roar back,” says Bridget Gibbons, economic-development head of the suburban New York City region that is already home to many of the nation’s most storied companies. “Companies with large headquarters are studying whether they want 10 floors in midtown Manhattan or a hybrid model so they can downsize their space—and come to us.” If, of course, Florida doesn’t get them first. CE