28 minute read

LEADERS

GAME, CHANGE

These companies are winning on employee engagement by bringing play into the workplace. You can, too. BY DALE BUSS

Advertisement

UNITED NATURAL FOODS HAD A secret weapon in its $2.9 billion acquisition of SuperValu last year: a mobile-game app. The contest asked SuperValu workers multiple-choice questions about their new employer, such as, “About how many new items per month is UNFI first to market with?” Four options ranged from 500 to 10,000.

The correct answer was 1,000. Those who answered questions correctly most often won points toward gift cards—and UNFI got better-informed new workers. “Setting up an environment of competing against others fuels the desire of employees to go out and learn,” says Jeremy Ford, vice president of people and change for the Providence, Rhode Island-based distributor. “A lot of it is just doing things in a novel and different way that they haven’t seen before.”

There’s a difference between making work fun and making a game out of work. Fun is “Bring Your Pet to the Office Day” and factory-wide ping-pong tournaments. “Gamifying” work is integrating elements of play, competition and digital technology directly into jobs to engage employees, communicate effectively and save time and money—or all of the above.

It can be turning information conveyance into a quiz, with leaderboards and prizes. It can be a software hackathon. It can be applying virtual-reality simulation to any training. And it can be war-gaming how to operate a new product—or how to run a machine tool that makes a new product. By any definition, gamification is hot.

“Sometimes things can get mundane,” says Martin Woll, chief operating officer of AXA, a New York City-based insurer that uses an online gamification platform to motivate internal wholesalers and runs their individual sales results leaderboard, ticker-style, across all the computer monitors in the office. “Gamification reinvigorates the competitive spirit and individuals competing because it’s fun. They can even trash talk.”

Catherine Monson agrees. “This is the best, coolest way to deliver training and increase retention,” says the CEO of FastSigns International, a Carrollton, Texas-based franchisor of custom-graphics stores that uses three-minute quizzes on mobile apps to get employees to remember important stuff. “And that’s what we as CEOs want to do.”

Waltham, Massachusetts-based Raytheon leverages what Harry Buhl, its lead investigator for synthetic training, calls the “gaming savvy of this generation of [military] recruits” by gamifying soldiers’ training on weapons ranging from helicopters to its Patriot air- and missile-defense system, making them operate very much like popular video games.

Rockwell Automation essentially bought a company just for gamification. Last year, the Milwaukee-based industrial giant acquired Emulate3D, a UK-based concern whose software enables customers to virtually test machine and system designs before incurring manufacturing and automation costs and committing to a final design.

There are some critics of corporate gamification. “The practice has the potential to degrade meaningful and fulfilling work and vital co-worker connections,” says Reid Blackman, a corporate-culture consultant. “It can be viewed as an attempt to squeeze greater efficiency out of workers in a thoughtless way.”

CEOs who’ve gotten gaming to work offer these tips on getting it right:

Facilitate training. FastSigns is rolling out a gamification platform across various functions after successfully using it with outside salespeople. Now it’s using games to onboard new franchisees, with quizzes around toughto-teach topics such as product knowledge and advice for signing a real estate lease. “In three to five minutes, they learn something,” Monson says. “All of this information has been in a 60-page booklet that we send new franchisees. Twenty years ago, people read the booklet. Today, they don’t.”

Encourage information retention. Just like in school, employees pay more attention if they know they’re going to be quizzed on something.

“You spend $20,000 on a speaker, and he might make six great points that you want people to understand, but people are checking their phones and email as they listen,” Monson says. “So we create a game out of questions about the key points. People want to get the highest score.”

Use it for recruiting. In a recent survey by TalentLMS, 78 percent of respondents said that gamification in the recruiting process would make a company more desirable. There’s even a moniker for it: “recruitainment.”

Rockwell, for instance, in December hosted a hackathon it called 24toCode, with a $10,000 grand prize aimed at recruiting software writers. “We were leveraging the comfort of new generations with digital technologies and evaluating their performance and seeing how well they might be able to do for our company,” says Dave Vasko, Rockwell’s director of advanced technology.

Show them the money. Workers tend to value monetary prizes most. “Point systems and virtual rewards and the AT LEFT: Rockwell awarded a $10,000 prize to the winner of its “24toCode” hacakthon.

ABOVE: FastSigns Quiz app help new franchisees get up to speed on products and practices.

Gamification companies like Mivation turn product knowledge into quizzes and scoring methodologies.

like aren’t what people want,” says John McKnight, a professor at the Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, in Pennsylvania. “They would rather have actual bonuses.”

Equivalents such as trips, gift cards and iPads also appeal. And employers shouldn’t sweat the outlays. “There’s not a big financial investment required to drive these games,” says Brian Hamilton, vice president of Ramsey Solutions, a Nashville-based provider of financial-literacy programs. “Do a $25 gift card giveaway each day, and it’s only $700 over a month.” Do it yourself. While he likes the concept of gamification, CEO Scott Moorehead decided that Round Room, a smartphone retailer based in Carmel, Indiana, would do its own. “It’s easy to do in Excel, and cheaper,” he says.

United Natural Foods wanted to create a gamelike video for orientation of distribution-center workers but saved tens of thousands of dollars by creating its own instead of outsourcing the project, strapping a VR camera to a drone and then to a box making its way through the warehouse.

Beware a ho-hum reaction. While much gamification leverages consumers’ recent experiences with gamification by brands and the interest of younger workers in digital games, those advantages may disappear with Generation Z. “They’ve grown up with them so they’re very savvy customers of online games and consumer apps,” McKnight warns. “They’re on to all the techniques, and many see them as phony and manipulative.”

Update continuously. Players want to know where they stand at the moment, not just periodically. “It’s important to give people real-time updating of their standing on the leaderboard because then they know if they stay an extra hour or come in earlier, they can beat the competition,” Woll says. “And that’s good for us because it helps motivate them.”

Outsource the task. Turnkey providers such as 1Huddle and Mivation will take any pile of corporate information, create quizzes out of it, maintain scoring and help clients communicate with players. “We enable you to set up competitions on any metric you can track,” says Seth Preus, senior adviser to Spokane, Washington-based Mivation. Take an ethical approach. Blackman worries that gamification can “harm a company’s overall people strategy” by “breeding a lot of unhealthy competition among employees.” For example, he says, “If the game looks like it’s supposed to be fun and about points, but it actually has an effect on your bonus or promotion, then you’re playing the game for the wrong reasons.”

CE Don’t use it as a crutch. Gamification shouldn’t try to compensate for work that isn’t interesting per se, Blackman argues. “Ideally what people want is intrinsically motivating work,” he says. “Gamifying it may just tell workers that their work isn’t intrinsically interesting.”

Luxury vacation homes, experiences, and so much more

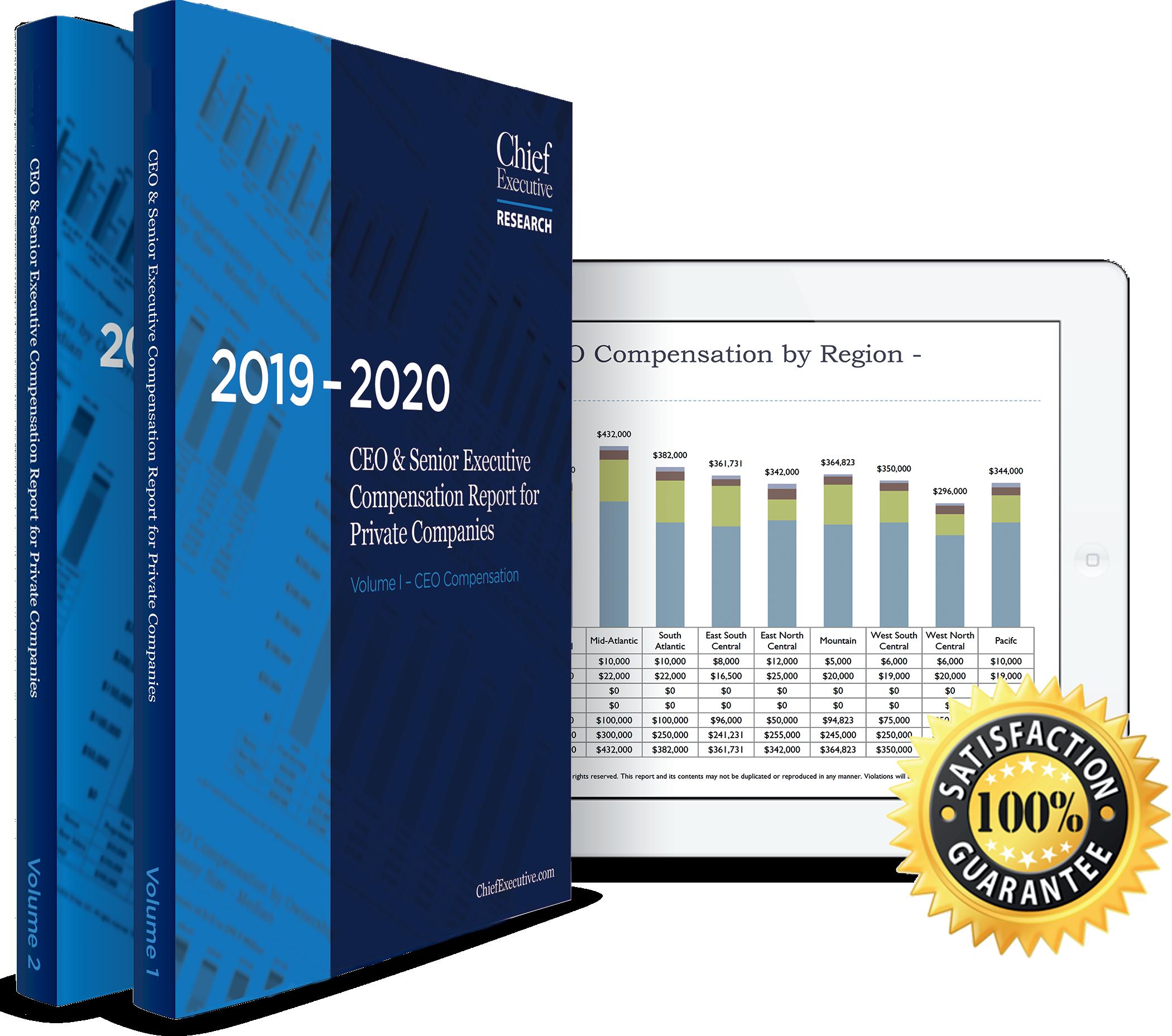

The information you need to make critical talent retention and recruiting decisions.

You won’t find a resource like this anywhere else.

With more than 35,000 data points—including values by industry—this resource will allow you to structure the right combination of salary, bonus, benefits, perks and equity incentives to attract top talent and retain the talent you have.

The new 2019-2020 CEO & Senior Executive Compensation Report for Private Companies reveals how the absolute dollar amounts and mix of components vary by position and:

• Company annual revenue • Number of employees • Industry • Geographic region • Type of ownership • Revenue growth • Profitability margins • and other key factors

To order your copy of the report, call 615-592-1169 or visit: chiefexecutive.net/compreport

RESEARCH

LAW BRIEF \ DANIEL FISHER SAVED FROM THE STATES

How a lawsuit playing out in an obscure Minnesota jurisdiction could bring a reprieve from product liability lawsuits.

Daniel Fisher, a former senior editor at Forbes, has covered legal affairs for two decades. SOMETIME THIS SPRING, THE U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case that could fundamentally change how product liability lawsuits are handled in U.S. courts. It involves the seemingly

arcane subject of jurisdiction, or whether a court has the authority to decide a case. In Ford v. Bandemer, the Minnesota Supreme Court decided that Ford Motor Co. could be sued in state court over a 2015 accident in which Adam Bandemer was injured after the 1994 Crown Victoria he was riding in slammed into the back of a snowplow. Bandemer claims the Crown Vic’s airbag failed to deploy.

Ford doesn’t deny it made the car. But it says the auto was manufactured in Ontario, sold in North Dakota and only wound up in Minnesota after 17 years and several transactions on the used-car market. While Ford sells thousands of cars each year in Minnesota, it didn’t sell this car, the company argues, and it shouldn’t be forced to appear before a potentially unfriendly Minnesota jury to defend itself.

A decade or so ago, this argument would have been laughable. Generations of judges and legal scholars had established the idea that companies could be sued over products they released “into the stream of commerce,” as courts put it, regardless of where they were based or where the products were made. The foundational decision also involved a car: In MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co., Justice Benjamin Cardozo, then a New York judge, ruled the Detroit auto manufacturer could be sued in state court after the wooden wheel on the plaintiff’s 1909 runabout fell apart, rejecting arguments that the customer could only sue the New York dealer that sold him the car.

State courts soon became an arm of the regulatory machine, handing down expensive verdicts that plaintiff attorneys and their academic supporters said provided an important check on corporate greed. California, ever the tort law innovator, edged toward imposing strict liability for any product a hypothetical “reasonable” person would find dangerous. Lawyers started gathering plaintiffs from multiple states and even foreign countries in “magic jurisdictions” known to deliver hefty jury verdicts.

Then, the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in. Citing the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of due process, the high court ruled companies must be have “continuous and systematic” connections with a state to be sued there, and state courts can only exercise so-called “specific jurisdiction” over cases involving activities that occurred within the state.

Now, manufacturers and business associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce are urging the Supreme Court to go a step further and set boundaries on what constitutes an activity within the state.

“Ford had nothing to do with the fact the car ended up in Minnesota,” says Andrew Pincus, an attorney with Mayer Brown who has filed briefs in Ford v. Bandemer on behalf of the Chamber. “Our whole theory is the company’s activities in the state must have a sufficient connection to the plaintiff’s claim in order to subject the company to personal jurisdiction.”

Minnesota’s highest court said it was enough that Ford sold lots of cars in the state and ran advertising urging Minnesotans to buy more. But Ford says there has to be a more direct link to the injuries it is being blamed for causing. Will the Supreme Court agree? Doing so could dramatically change the fate of product-liability litigation in the U.S.—and, not incidentally, put a dent in the income of some of the nation’s richest and most powerful lawyers. CE

‘THERE ARE THREE THINGS I BELIEVE’ In this latest installment of our series of interviews with high-performing members of the CEO1000, leaders of the 1,000 largest U.S. companies by revenue, new Domino’s CEO Ritch Allison talks about handling the company’s challenges—and following an excellent predecessor.

RITCH ALLISON BECAME CEO OF DOMINO’S IN JULY 2018 at a challenging moment. His predecessor had just led the company on a very successful 10-year tear. And third-party home food-service delivery was becoming a hugely disruptive competitive challenge for the Ann Arbor, Michigan-based leader of the global pizza business.

But Allison has reaffirmed Domino’s dedication to handling its own delivery and to relying on home-grown digital technology to expand and streamline how customers can order and receive pizzas. “Fundamentally, I don’t want to put another entity between Domino’s Pizza and our customers,” says Allison, who was co-leader of the restaurant practice of Bain & Co. before joining Domino’s in 2011 and soon becoming president of the chain’s immense international operations. And the 52-year-old has already put his stamp on the CEO job at Domino’s, including appearing in one of the brand’s TV ads.

Allison’s approach to leadership is an amalgam. “I’ve tried to take the best elements I’ve observed in leaders I’ve worked for and avoid those I thought were the least productive, blend them in with my own philosophy and personality, and make them my own,” says Allison, No. 790 on our CEO 1000 list.

In these excerpts from a recent interview, Allison discussed his management principles and challenges. (The full interview is available at ChiefExecutive.net/CEO1000.)

What’s your approach to leadership with your senior executive team?

I try to be empowering, and by that I mean there are three things I believe I need to do in that capacity. First, I’m responsible for setting a vision and a set of objectives for the business, both in the long term and also with near-term waypoints to get there. Second, I believe it’s my duty to ensure that my team has the resources and capabilities to achieve that vision and those objectives. And third, I then need to hold the team—and their support teams along the way—accountable. If I can stay aligned with my team in that way, we can be successful. What did you learn from heading international operations that you now apply to running the entire Domino’s business?

A lot of American companies fail internationally because they assume everyone else will like what Americans like or assume we can just send expats around the world to show them what we do. We have taken a different approach. We try to recognize that good ideas come from all over the world and don’t just originate in Ann Arbor. We try to accelerate the transfer of good ideas and best practices from around the world to maximize our potential overall as a brand.

Domino’s now has more staffers involved in digital tech than food development—or anything else. Did you know you’d be running a tech company?

In a tech-enabled world, the rollout of a new platform or ad campaign that’s tech-enabled demands a cross-functional effort across a company. People have to be much more adept at cooperating with their peers from other parts of the company, who have very different backgrounds and experiences and skills. As leaders, we have to blend them into an effective team.

What has it been like following Patrick Doyle, who really turned around Domino’s as CEO?

With a company that already was performing well under a great leader, I could come in without having to restructure or make a radical change early on. That gave me the time to really think about how we accelerate the things that are working really well and about what additional changes we might want to make as we drive the business forward.

DO A CULTURE AUDIT PERFORMANCE \ RAM CHARAN

CEO focus on the business buzzword of the decade isn’t helping improve actual performance. Here’s what will.

Ram Charan is a worldrenowned business adviser, author and speaker who has spent the past 35 years working with many of the top companies, CEOs and boards of our time. His latest book, The Amazon Management System (Ideapress, 2019), was a Wall Street Journal bestseller. ON BOEING’S RECENT Q4 EARNINGS call, an analyst asked CEO David Calhoun a simple, difficult question: “How do you change the culture of a big organization?”

“Boy, is that a big question,” he responded. And it is. Culture is the most-discussed issue facing business leaders right now. From #MeToo to motivating millennials, leaders are being asked to create “purpose-driven” cultures that innovate, grow, respect and, in some cases, flat-out love one another.

Yet, these discussions give CEOs little help in actually homing in on what’s driving their organization. That’s because they encourage CEOs to look in the wrong places. If you really want to know what’s going on in your organization, you need to do what I call a culture audit.

Culture Shock Let’s step back. What are we talking about when we talk about culture? Whenever two or more people work together, their work together has a social architecture. What is it? How do they interact with each other, trust each other? Who dominates, and why? How well do they debate and create? What data or unwritten rules do they use in making decisions? What are their motivations, and how driven are they? That’s a lot.

A larger team brings still more elements. Team members change. They may be from different functional silos, with different backgrounds and access to different sets of data. Many don’t communicate well, or at all. People from all over the world bring elements of their national cultures. There is often unhealthy competition within teams, and some members may take shortcuts that come to haunt the entire company, as happened at Volkswagen, Wells Fargo and Boeing.

Let’s stick with Boeing for a minute. Lots of people suggest that what happened with the 737 Max was a “result of the culture.” That isn’t really useful in helping leaders make meaningful changes. How do they ensure a similar problem doesn’t happen again? Decision Points The answer is to look in the right places, where the elements of culture matter most. In examining Boeing, I would focus on the decision points that resulted in the problems—not the decisions themselves, but the circumstances that produced the decisions. To fix what ails Boeing, you don’t need to understand the whole of Boeing, but you do need to understand where and how it makes key decisions. To monitor culture, monitor decision points. The culture at each decision point in the company is what drives corporate performance, what drives output. It can be the intersection among silos where decisions get made. It could be a flow of decisions before a final decision. Ask: Who is involved? Who ultimately makes the decision? How? What data is used? What behaviors are used? What are those interactions like? Is there intimidation? Do some people dominate? Through interviews at each decision location in the company’s architecture, you can see the spots that are good and the spots that are not. That’s the culture audit. Then you can start to monitor those areas, maybe quarterly or annually. (Full disclosure, I am working on a software tool to facilitate culture audits. It is being tested in two companies.)

The CEO must get his CFO and CHRO together to define the network of decisions in their areas. They should start from the top down, looking at the decisions the CEO and his or her direct reports are making. Dig in on something common, like pricing. How do these choices get made? What are your decision points? Who exerts influence and who makes the final decision? What information is brought to bear, and what is the behavior of those involved?

Then you can chart decisions about promotions. What is the culture around deciding who will progress? Go to each decision point, and you will see, over time, how clean that process is. This is where—and how—to look at your culture. And how to actually do something about it. CE

Risk shouldn’t be a guessing game. Make sure you know your score.

You can't manage what you can't measure, so why don't more organizations measure and correlate human behavior to risks? It’s time to handle people risk the same way you handle the rest of your business decisions…with data.

True Office Learning extracts behavioral analytics from everyday training, and brings it together with other data to help you create a comprehensive risk scorecard for your organization.

Ready to take the guesswork out of risk? That’s where we come in.

SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I GO? ON LEADERSHIP \ JEFFREY SONNENFELD

What to think about when timing your exit.

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld is senior associate dean, leadership studies, Lester Crown professor in management practice at Yale School of Management, president of the Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute and author of The Hero’s Farewell. Follow him on Twitter @JeffSonnenfeld SURELY THE CLASH, AN ENGLISH punk rock band, had CEOs in mind with their 1982 No. 1 hit “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” This new decade launched with the news that CEOs of varied iconic firms as IBM, United Airlines, Boeing, T-Mobile, L Brands, Bridgewater and NBCUniversal were stepping down in 2020.

This stream of departures is perhaps not surprising, given that average CEO tenure has fallen to five years at larger companies—somewhat disturbing when research suggests it takes roughly two years to truly master the job. Last year, 1,640 CEOs stepped down, a 12 percent jump over 2018—which itself was a record year.

As always, some exits were forced, but the vast majority of prominent departures were voluntary—which begs the question: How do you, as the boss, know when it’s time to go? I wrote a book on different CEO departure styles called The Hero’s Farewell 30 years ago—recommended reading for any CEO stepping down—but it didn’t address that question. However, working with CEO successions over the past 40 years has surfaced five key sets of motives:

1) Quitting while ahead 2) Mentors passing baton to colleagues 3) Skills changes for sea changes 4) Exhaustion from a fractious board 5) Hostile activist shareholder base 6) New compelling missions 7) A health or family crisis TV host Johnny Carson set a great model for CEOs considering the quit-while-ahead path. After a great 30-year run, while still king of late night, Carson saw competition cutting his audience by 42 percent over five years and advertiser rates falling. In May 1992, 67-year-old Carson made a surprise announcement: “Everything comes to an end. Nothing lasts forever... it’s time to get out while you are still on top of your game.” Surely, Indra Nooyi’s highly profitable mar- ket triumphs coupled with the ESG model of “performance with purpose” reign represented similar career gratification.

Regarding those who pass the baton, inspiring CEOs like Anne Mulcahy of Xerox, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and John Legere of T-Mobile each told me that while they did not feel their missions were complete, they had made a commitment to successors who deserved a chance. Had they stayed on longer, they would have blocked such opportunities. Others leave to bring needed skills into the corner office. Ginni Rometty of IBM believed a cloud/AI computer scientist with business leadership skills was the right leadership profile for the company she transformed. Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg realized he had hit such wall of credibility with regulators and air carriers that his chairman, a battled-tested, trusted former CEO, would bring a new voice. The CEO’s job is far less fun than the old days of secure stature, fancy clubs and modest travel. Jeff Kindler, former CEO of Pfizer, confided to simply being fed up with the constant backstabbing on his board, crushing scrutiny and governance politics, plus 200 days a year on the road.

A CEO of a huge travel industry firm told me that, despite loving the job, when his ownership base became 40 percent activists, he had no choice other than to get shareholders a great stock price by selling out to a competitor. Then, there are those lured by a challenge, such as Dave Cote, who left TRW to turn the troubled industrial conglomerate Honeywell around, and former eBay CEO John Donahoe leaving ServiceNow to take the helm at Nike. Finally, there’s “spending more time with family,” especially common among CEO when they or loved ones face a health crisis. Starbucks entrepreneur Howard Schultz, Verizon transformer Ivan Seidenberg, BNSF’s Mike Rose and Dunkin Brands’s Nigel Travis all exited voluntarily to enjoy family and spend time pursuing other life interests.

Increasingly, CEOs realize their identities are not defined by their business cards and titles. And that is a healthy trend. CE

CREATING SHAREHOLDER VALUE THROUGH M&A—AND BEYOND

OST ACQUISITIONS by public companies fail to create long-term value for their shareholders. However, a few companies have demonstrated the ability to consistently generate shareholder value through inorganic investments. What distinguishes these companies is a set of decision standards and integration skills that lead to outstanding returns on external investment. M

How are value-creating acquirers different? Value-creating corporate M&A programs focus on three key deal requirements:

• Attractiveness: What are the economic profit pools in the target’s market, what is the level and driver of the target’s share of those economic profit pools, and how does the target’s business model align with the acquirer’s?

• Affordability: What are the opportunities to recapture acquisition premiums and how do they compare to the transaction price?

• Integration: What are the key actions needed to align the company’s strategy, operations and governance in order to improve cash flow and re-capture the control premium associated with most acquisitions?

When deals fail to create value for the acquirer, it’s usually because one or more of these considerations has been overlooked or insufficiently vetted. The most common problems are:

1) Strategy Failures: Buying companies that are exposed to markets with limited economic profit pools and/or have little ability to capture share of those economic profit pools. This often occurs when management pursues topline growth without fully understanding the concentration of profit pools in the target’s markets and where and why the target captures share of those profit pools.

2) Pricing Failures: Paying transaction prices that exceed the value of the target after accounting for all combination benefits and costs. This is usually the result of overly optimistic assumptions about the size of cost and revenue synergies, the incremental investment that may be needed and especially the time required to realize those opportunities. It can also be due to internal political pressure to “get the deal done” that makes it more difficult for well-intentioned managers to walk away from deals when prices become economically unattractive.

3) Integration Failures: Failing to define the actions and accountabilities needed to align strategies and operations of the combined business and establish the governance conditions to track integration, manage performance commitments and drive further value creation post-integration.

Acquirers who consistently create shareholder value recognize these challenges and use repeatable, systematic processes, prescribe required deal information and set clear decision “gates” with explicit go/no-go criteria to develop thorough plans for integrating both operations and strategy well in advance of the deal close. Most importantly, executive management and Boards of these companies constantly reinforce the discipline to stick to these governance standards.

What governance conditions and leadership characteristics ensure disciplined M&A practices are followed?

Clear definition of winning: Successful acquirers begin with a clear understanding that “winning” means sustainably creating more shareholder value than peer companies. They also know that “winning” in the capital markets requires “winning” in their product and customer markets—by creating more value for customers and capturing a larger share of the resulting profit pool than competitors. They also “win” with employees, attracting and retaining talent better than competitors. When companies do so, they build a reinvestment advantage that strengthens their competitive position and drives superior shareholder returns over time.

TransDigm Group, a highly acquisitive provider of commercial and military aerospace components, is one such company. Management and the Board set the clear objective of delivering “Private Equity-Like Growth in Value with Liquidity of a Public Market” and target total shareholder returns of 15 to 20 percent per year. The company exceeded that goal over the last 10 years, delivering compounded annual total shareholder returns over 35 percent, well above its peers and in the top decile of the S&P 500.

Focus on where and why shareholder value is being, or can be, created: Over 100 percent of the value of most businesses is generated by less than 40 percent of employed capital, while 25 to 35 percent of employed capital often destroys shareholder value. Successful acquirers

understand that value is concentrated. They begin with a granular and quantified view of where and why the markets, products and customer segments in their own business, as well as the target’s, are and are not economically profitable over time.

A robust understanding of these concentrations provides useful due diligence intelligence and builds a concrete understanding of where and how to improve the value of the combined businesses. This value growth “agenda” of opportunities sets a clear upper limit for the transaction price and helps the company build specific and robust integration plans well ahead of close.

Illinois Tool Works (ITW) employs its “80/20 Front to Back” process to identify the 20 percent of its businesses, markets, products and customers where profit, growth and value are concentrated. Following its process, ITW selectively pursues acquisitions that will be accretive to its long-term organic growth and where it can improve profit margins to ITW-caliber returns. ITW aims for its acquisitions to match its own margins by the end of year seven and generate a 10-year return on invested capital above 20 percent. As a result, ITW has grown economic profits by 14 percent compounded annually over the last five years, nearly triple the rate of its peers, and delivered top quartile shareholder returns.

Manage to a continuous value growth agenda: Having already identified and defined plans for realizing the largest value creation opportunities in the combined business, upon closing these acquirers can immediately begin executing the required integration actions. This provides clear direction and structure for post-close activities, including accountability for achieving each opportunity and managing progress of each initiative against strategic and financial objectives.

The same process that helped form this integration agenda also drives additional organic value growth post-integration. By updating key facts about where and why value growth opportunities are concentrated in the combined business and adjacent markets, management can refresh its value growth agenda with new opportunities, evaluate new strategy alternatives and resource allocation choices, and continue managing execution. Danaher Corporation uses its Danaher Business System (DBS) to guide the company’s culture, organic growth and M&A activity. The company implements DBS across its entire portfolio, describing it as “who we are and how we do what we do”, and uses it to drive “a never-ending cycle of change and improvement”. This dis

Danaher, ITW and TransDigm Total Shareholder Returns vs Peers

As os 12/31/2019 1-Yr TSR 3-Yr TSR 5-Yr TSR Danaher 49.6% 26.1% 19.3% Weighted Peer Average 31.5% 25.7% 18.6% S&P 500 31.4% 5.3% 11.7% Danaher Outperformance vs. Peers +18.1% +0.4% +0.7% ITW 45.6% 16.4% 16.3% Weighted Peer Average 37.2% 15.3% 10.8% S&P 500 31.4% 15.3% 11.7% ITW Outperformance vs. Peers +8.4% +1.1% +5.5% Transdigm 84.4% 39.7% 30.5% Weighted Peer Average 31.0% 19.1% 14.6% S&P 500 31.4% 15.3% 11.7% Transdigm Outperformance vs. Peers +53.4% +20.6% +15.9%

Source: Company Financials, Factset

ciplined and continuous approach to managing the value of its businesses has helped Danaher deliver compounded total shareholder returns of 19 percent over the past five years, outperforming the S&P 500 by nearly 8 percent.

Implement differentiated business models and differentially allocate resources: TransDigm, ITW and Danaher are examples of firms with distinct and disciplined management processes. These capabilities lead to highly differentiated business models and disciplined allocation of resources and enable M&A to contribute to shareholder value growth long after acquisition integration, resulting in sustainable shareholder returns well above their peers.

Sharpen organizational conditions and capabilities: Mergers and acquisitions are inherently challenging and require a disciplined focus on execution long after closing the transaction. Ultimately, the success of the deal and continued value creation of the acquirer depend on a culture where employees think and act like entrepreneurial owners. When continually applied, the same principles and processes that help make value creating acquisitions also build the ongoing management capabilities that maximize organic value creation and ultimately create a formidable reinvestment advantage that is difficult for competitors to overcome.