25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, December 4, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, December 5, 2025, at 1:30 Saturday, December 6, 2025, at 7:30 Sunday, December 7, 2025, at 3:00

Petr Popelka Conductor

Julia Bullock Soprano

BRAHMS Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90

Allegro con brio

Andante

Poco allegretto

Allegro

INTERMISSION

AUCOIN Song of the Reappeared El mar (The Sea)

Una ruta en las soledades (A Path in the Solitudes) Rompientes (Breakers)

CSO Commission. World premiere

Commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra through the generous support of Sarah Billinghurst Solomon and Steve Novick

JULIA BULLOCK

STRAUSS Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Op. 28

Thursday’s concert is sponsored by Sheppard Mullin. The appearance of Julia Bullock is made possible by the Grainger Fund for Excellence. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

Newsradio 105.9 WBBM is a Media Partner for this event.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to Sheppard

for its generous support.

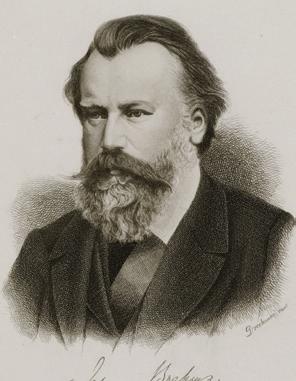

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born May 7, 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died April 3, 1897; Vienna, Austria

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra played Brahms’s Third Symphony in its very first season. By then, Johannes Brahms, still very much alive, had stopped writing symphonic music. It was a time of tying up loose ends, finishing business, and clearing the desk. (At the end of that season, in the spring of 1892, Theodore Thomas, the Orchestra’s founder and first music director, invited Brahms to Chicago for the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition, but the composer declined, saying he didn’t want to make the long trip.) It’s hard today to imagine that Brahms’s Third Symphony was once a challenging work of contemporary music. Yet several hundred people walked out of the first Boston Symphony Orchestra performance in 1884, and the critic for the Boston Gazette called it “painfully dry, deliberate, and ungenial.” (It had been introduced to America a month before at one of Frank van der Stucken’s Novelty Concerts in New York.)

Even when Brahms’s music was new, it was hardly radical. Brahms was concerned with writing music worthy of standing next to that by Beethoven; it was this fear that kept him from placing the double bar at the end of his First Symphony for twenty years. Hugo Wolf, the adventuresome song composer, said, “Brahms writes symphonies regardless of what has happened in the meantime.” He didn’t mean that as a compliment, but it touches on an important truth: Brahms was the first composer to develop successfully Beethoven’s rigorous brand of symphonic thinking.

Hans Richter, a musician of considerable perception, called this F major symphony Brahms’s Eroica. There’s certainly something Beethovenesque about the way the music is developed from the most compact material, although the parallel with the monumental, expansive Eroica is puzzling, aside

this page : Johannes Brahms, engraved portrait by Hermann Dröhmer (ca. 1820–1890) and L. Angerer (1827–1879), 1882. Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky Collection | next page : General View, Wiesbaden, Hesse-Nassau, Germany, ca. 1890–1900, where Brahms rented a studio in the summer of 1883 and wrote his Third Symphony. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

COMPOSED 1882–83

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 2, 1883; Vienna, Austria

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

40 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

April 22 and 23, 1892, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 11, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Hans Lange conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 15, 2011, Ravinia Festival. Christoph von Dohnányi conducting

October 24, 25, and 29, 2019, Orchestra Hall; October 26, 2019, Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. David Afkham conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1940. Frederick Stock conducting. Columbia

1957. Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1976. James Levine conducting. RCA

1978. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1993. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Erato

from the opening tempo (Allegro con brio) and the fact that they are both third symphonies. Brahms’s Third Symphony is his shortest and his most tightly knit. Its substance came to him in a relatively sudden spurt: it was mostly written in less than four months—a flash of inspiration compared to the twenty years he spent on his First Symphony. Brahms was enjoying a trip to the Rhine at the time, and he quickly rented a place in Wiesbaden, where he could work in peace, and canceled his plans to summer in Bad Ischl. The whole F major symphony was written nonstop.

The benefit of such compressed work is a thematic coherence and organic unity rare even in Brahms. Clara Schumann wrote to Brahms on February 11, 1884, after having spent hours playing through the work in its two-piano version: “All the movements seem to be of one piece, one beat of the heart.” Clara had been

following Brahms’s career ever since the day he showed up at the door some thirty years earlier, asking to meet her famous husband Robert. By 1884, Robert Schumann—Brahms’s first staunch advocate—was long dead, and Brahms’s on-again-off-again infatuation with Clara was off for good. But she was still a dear friend, a musician of great insight, and a keen judge of his work.

Surely, in trying to get her hands around the three massive chords with which Brahms begins, Clara noted in the top voice the rising F, A-flat, F motive that had become Brahms’s monogram for “frei aber froh” (free but joyful), an optimistic response to the motto of his friend, the virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim, “frei aber einsam” (free but lonely). It’s one of the few times in Brahms’s music that the notes mean something beyond themselves.

That particular motive can be pointed out again and again throughout the symphony—it’s the bass line for the violin melody that follows in measures three and four, for example. Clara also can’t have missed the continual shifting back and forth from A-natural to A-flat, starting with the first three chords and again in the very first phrase of Brahms’s cascading violin melody. Since the half step from A-natural down to A-flat darkens F major into F minor, the preeminence of F major isn’t so certain in this music, even though we already know from the title that it will win in the end.

In four measures (and as many seconds), Brahms has laid his cards on the table. In the course of this movement and those that follow, we can trace the progress of that rising threenote motive, or the falling thirds of the violin theme, or the quicksilver shifts of major to minor that give this music its peculiar character. This is what Clara meant when she commented that “all the movements seem to be of one piece,” for, although Brahms’s connections are intricate and subtle, we sense their presence throughout.

For all its apparent beauty, Brahms’s Third Symphony hasn’t always been the most easily grasped of his works. Brahms doesn’t shake us by the shoulders as Beethoven so often did, even though the quality of his material and the logic of its development is up to the Beethovenian standards he set for himself. All four movements end quietly—try to name one other symphony of which that can be said—and some of its most powerful moments are so restrained that the tension is nearly unbearable.

Both the second and third movements hold back as much as they reveal. For long stretches, Brahms writes music that never rises above piano; when it does, the effect is always telling.

The Andante abounds in beautiful writing for the clarinet, long one of Brahms’s favorite instruments. (The year the Chicago Symphony first played this work, Brahms met the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, who inspired the composer’s last great instrumental works, the Clarinet Trio and the Clarinet Quintet.) The third movement opens with a wonderful arching theme for cello—another of the low, rich sounds Brahms favored—later taken up by the solo horn in a passage so fragile and transparent it overrules all the textbook comments about the excessive weight of Brahms’s writing.

There is weight and power in the finale, although it begins furtively in the shadows and evaporates into thin air some ten minutes later. The body of the movement is dramatic, forceful, and brilliantly designed. As the critic Donald Tovey writes in his famous essay on this symphony, “It needs either a close analysis or none at all.” Two things do merit mention. The somber music in the trombones and bassoons very near the beginning is a theme from the middle of the third movement (precisely the sort of thematic reference we don’t associate with Brahms). And the choice of F minor for the key of this movement was determined as early as the fourth bar of the symphony, when the cloud of the minor mode crossed over the bold F major opening. Throughout the finale, the clouds return repeatedly (and often unexpectedly), and Brahms makes something of a cliffhanger out of the struggle between major and minor. The ending is a surprise, not because it settles comfortably into F major, but because, in a way that’s virtually unknown to the symphony before the twentieth century, it allows the music to unwind, all its energy spent, content with the memory of the symphony’s opening.

MATTHEW AUCOIN

Born April 4, 1990; Boston area, Massachusetts

I first knew Matt Aucoin as a conductor. When I served as one of the judges for the Solti Conducting Apprentice position here at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2013, I had not yet heard a note of his music. His résumé was already large and full of adventure: he had played in a rock band in high school (it was called Elephantom), and he had recently graduated from Harvard, where he studied poetry with Jorie Graham and Helen Vendler; he was an assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera (while he was studying at the Juilliard School with composer Robert Beaser). Over the next few years, his career took off at rocket speed as a “quadruple threat”: composer, conductor, pianist, writer. In 2016 he was named the first-ever artist-in-residence at Los Angeles Opera, where he conducted several productions, including Verdi’s Rigoletto, Philip Glass’s Akhnaten, and his own operas, Crossing (based on Walt Whitman’s Civil War diaries) and Eurydice (a co-commission with the Met). In 2017 he and director Zack Winokur cofounded the American Modern Opera Company. He was named a MacArthur Fellow—the so-called Genius Award—in 2018 (he was the youngest of the twenty-five fellows that year). His book on opera, The Impossible Art, was published in 2021, and he is a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books, where he has written about the legendary conductor Carlos Kleiber, the operas of Kaija Saariaho, and the state of musical criticism today.

Aucoin has been commissioned by a wide range of organizations, including Lyric Opera of Chicago (for Second Nature, a 2015 work set in the future, about healing the planet), Carnegie Hall, American Repertory Theater, the Peabody Essex Museum, and NPR’s This American Life. Among his most recent compositions is the music-theater piece, Music for New Bodies, a collaboration with director Peter Sellars based on the poetry of Jorie Graham. Song of the Reappeared is his first work for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, where he worked with Riccardo Muti as our Solti Conducting Apprentice from 2013 to 2015. Matt spoke with me recently about conducting, composing, and being an artist in today’s world.

COMPOSED 2025

INSTRUMENTATION

solo soprano, 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo and alto flute), 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (glockenspiel, cabasa, castanets, snare drum, seed pod rattle, tubular bells, suspended cymbal, crash cymbals, tom-toms, vibraphone, marimba, xylophone, sandpaper blocks, whip, bass drum, claves, rain stick), piano, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 22 minutes

Commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra through the generous support of Sarah Billinghurst Solomon and Steve Novick

These are the world premiere performances.

The Chicago Symphony first knew you as a conductor, after you were picked as the Solti Apprentice Conductor in 2013. Composers as disparate as Gustav Mahler and Esa-Pekka Salonen have struggled with finding a reasonable balance between composing and conducting. How’s that going for you?

Fairly early on, I realized that at the core of my being, I am a composer. I do love conducting, and I need the catharsis and the thrill and the communal experience of performing with wonderful fellow musicians. But when it comes down to it, I’m a composer. I’m most at home sitting in front of a blank page.

When I conduct for a long stretch—for example, if I’m conducting an opera with a fourweek-long rehearsal period—at a certain point a nagging voice starts up in my head: just think of all the music you could have brought into the world if you were back at your desk composing. I mourn the pieces that I didn’t write. I feel real guilt about it. Whereas the reverse isn’t true: when I’m at home composing, I don’t mourn the concerts that I didn’t conduct. I feel entirely at peace, even when it’s difficult. So that seems like final proof of what species I belong to!

I feel pretty good about the balance I’ve struck lately; I probably conduct for about three months out of the year and spend the rest of the time composing. The unfortunate thing is that I can’t do both at once: when I’m on a conducting project, the music I’m conducting fills my head, even at night, even after rehearsals end, and there’s rarely any bandwidth for composition. So I do have to separate the activities.

Is it true that hearing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony first made you realize the miracle that great music is?

Yes! I remember this very vividly. I was six years old, and I heard the Ninth being played somewhere—I can’t remember where, it might have been in public, possibly even in a shopping mall—and I was just dumbfounded. I remember thinking, how can there be anything this beautiful in the world?

Ten years ago, it was commonplace to talk about how you threw yourself headfirst into the world of music at a very early age. At the time, did you ever worry about becoming overextended or overexposed, concerns that used to surface regularly?

Sure. But I worked hard to counteract that risk by withdrawing and taking the time to write the music I needed to write. It would have been possible for me to lean into the strange burst of attention that came my way when I was about twenty-five—that New York Times Magazine profile and so on—to try to become music director somewhere, or even to start a YouTube series or podcast to become a kind of influencer or whatever. But I knew that it would have been disastrous for my music making to prioritize the public-facing side of things at the expense of the private, unglamorous, but essential work of listening to silence and finding the next note. To write music, I need lots of quiet and lots of unstructured time. And also, my music, a decade ago, wasn’t done developing. I didn’t even like some of the music I was writing at that time! So I decided it was more important to write good music than to try to be as famous as possible. Now, a decade later, I’m writing music that I believe in 100 percent, and that wouldn’t have been possible if I’d given in to various temptations along the way.

What was the essential thing you learned about conducting from working with Riccardo Muti here?

There’s an extraordinary simplicity to Riccardo Muti’s conducting, an extraordinary presence and focus. He frequently obtains astonishing results through simpler means than most conductors would need; his baton technique isn’t flashy or full of complicated tricks. This directness and intensity is part of what makes him such a wonderful match for Verdi.

You have conducted major works by several composers over the years, including John Adams’s opera Doctor Atomic in 2018. What do you learn as a composer by conducting the music of others? Do you imagine that your conducting career will continue to explore music other than your own?

Yes, you learn a lot, as a composer, from conducting other composers’ music. Conducting Doctor Atomic, I remember marveling at John’s mastery of what I would call the primary colors of the orchestra: treating the horns as one distinct color and the trumpets as another, for instance, rather than piling them on top of each other in a way that would muddy the waters. You also learn a lot about what does and doesn’t work. A particular rhythm might look cool on the page, but then you try to conduct it and you find it’s practically impossible for an ensemble to execute together. So the experience of performance informs my approach to notation, orchestration, everything.

In your book The Impossible Art, you argue that opera’s almost unreasonable combination of various art forms—creating what you call “another planet” altogether—is what makes it uniquely potent. Do you never feel the urge to focus exclusively on opera, in the mold of Verdi or Wagner?

That’s a good question. I do wish I had several lifetimes, and that I could devote one of them exclusively to composing opera. But I love orchestral and chamber music too much to do that. I have quite a few orchestral pieces inside me that I think need to find their way into the world. In fact, I’m just setting out now to compose a big orchestral piece that might possibly be an S-word (symphony).

You once called your music “explosively tonal.” Is that still what it tends to be? And what do you mean by that?

Tonality usually implies stability, groundedness, even—sometimes—a kind of predictability, a sense that the piece will find its way home, eventually, to the root of the chord. And I think

my music is “explosively” tonal in the sense that it’s usually based on tonal harmonies, but those harmonies don’t always behave in a stable way. My music is full of leaps between keys or keys that are only fleetingly or partially present. There is a tightrope to walk, I think, between writing music that’s so tonally stable that it feels stuck or complacent and writing entirely non-tonal music, which can feel, to me, like a kind of freefall. I find that the point of maximum expressive intensity is often when I have some kind of relationship to a tonal center, but it’s an elusive or dancelike relationship, not an easy or preordained one.

When you were awarded the MacArthur Fellowship, in 2018, you were singled out for “expanding the potential of vocal and orchestral music to convey emotional, dramatic, and literary meaning.” Is that still a fair appraisal of what you are trying to do?

I remember being very moved when the MacArthur committee quoted that description to me in their initial call when they told me about the fellowship. They asked, “Does that sound like an accurate description of your work?” and I said: well, it sounds like what I’m trying to do, but I’m not sure I’ve done it yet.

The world of classical music has a relatively small audience, and people regularly wring their hands over its demise. Do you worry about its so-called niche status? Do you think that it is endangered?

Classical music has been on the endangeredspecies list for a very long time, but I don’t think we’ll ever go extinct. Of course, we have to be vigilant: we have to make sure that our music is reaching the ears of as many people as possible— we have to make sure that everyone has a chance to experience orchestral and chamber music and decide whether it’s for them, whether they need it in their lives—and we have to make sure that young artists have the opportunities they need to grow and flourish.

But I’m also proud of our niche status. Classical music requires deep listening; Berg

and Stravinsky and Saariaho don’t make good background music. They demand your full attention. And to really break into the mainstream in American culture, your music has to be easy to ignore, it has to work as background music, it has to be simple, it has to be loud—or rather it has to be neither loud nor soft—it has to exist in this depressingly narrow band of dynamics, so that neither loudness nor softness can really be felt. Anyway, I’m proud that we’re not simple, that we’re not just loud, that we’re not background music. It’s a niche, sure, but it’s a niche that I hope is welcoming to anyone with curiosity and patience and open ears.

The shocking image of Chilean victims falling from the sky in Zurita’s poetry that you have set suddenly seems much closer to our world. Can music make us directly confront things that maintain a certain safe distance in the daily news?

Music and other forms of art can above all embody a way of being—in this case, a fierceness and a refusal to look away from injustice—that, I hope, can have a strengthening and inspiring effect on the listener. I don’t think music ever benefits from being jingoistic or on-the-nose, and that’s why I was drawn to Raúl Zurita’s poetry. He engages with social and political questions, but he doesn’t make the mistake of thinking it’s enough to merely “engage.” It’s also necessary to make visionary and blazing and powerful art! And Zurita transforms these nightmarish experiences into almost Rimbaudlike visions; his language has a biblical cadence; it drips with surreal beauty. He transforms great suffering into great power.

And I think art always has to do this at an angle, not head-on. If Zurita’s poems were merely accusations, addressed directly to Pinochet, they would probably be dull and forgettable, no different from an op-ed column. Instead, he summons these unforgettable visions of loss and resurrection.

We live in a world where confronting power head-on can feel crushing or futile. The artists I identify with know that it can be more powerful

to approach these questions from a mysterious angle and to speak in a language that the dumb and mighty powers of the world won’t understand. It’s a frequency that they’re not privy to. It’s a human speech, a message for those who know how to listen. It’s a form of love.

Song of the Reappeared is a concerto for voice and orchestra that features both the soprano soloist and the full orchestra in all their richness and virtuosity. I composed this piece with two voices in mind: the voice of Julia Bullock, an artist who brings a unique intensity to everything she performs; and the mighty collective voice of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The text that the soprano soloist sings is drawn from the blazing, visionary poetry of the Chilean writer Raúl Zurita, and the word ‘reappeared” in the title refers to the thousands of people who were “disappeared”—that is, murdered—in Chile throughout the repressive regime of the dictator Augusto Pinochet. Zurita was a politically active student poet when Pinochet seized control of the country in 1973, and within days of the coup, the young Zurita was imprisoned and tortured. After he was released, he was banned from entering any bookstore in the country, and in the subsequent decades he found ever more creative ways to share his work with his fellow countrymen, in acts of solidarity and nonviolent defiance: he wrote phrases of poetry out of stones in the Atacama Desert, so that they would be visible from the air; and he once orchestrated the writing of lines of poetry in the sky above New York, using the contrails of multiple airplanes.

About a decade after the end of Pinochet’s regime, the Chilean government acknowledged that the bodies of many of the dictatorship’s victims had been thrown out of the sky into Chile’s oceans, lakes, and mountains. This horrifying revelation made a deep impression on Zurita, ultimately inspiring him to write the book-length poem INRI both as a memorial to those many

lost victims and also as a potent, surreal vision of resurrection.

The texts of Song of the Reappeared come from this book, which is full of poetry that is positively biblical in its overflowing musicality, its inexorable cadences, and its images of the return of the dead. It seemed to me that this was poetry that cries out to be set to music. And I found myself invigorated, in the difficult moment we’re all living through, by Zurita’s conception of art as a nonviolent and life-affirming, yet also unyielding, form of resistance.

who was also lost: he speaks “as the stones speak, as the earth speaks,” mutely, through touch alone, with infinite tenderness.

Near the end of the second movement, the piece’s trajectory shifts when the speaker experiences a vision of resurrection: “And I see you! / And looking at me, blind and looking at me . . . you see me rising and rising and your eyes see my eyes full of earth rising.” This vision of the resurrection of the dead leads into the longest instrumental solos in the piece: the brass leads a massive, steady crescendo, like new mountains emerging out of the earth, pointing skyward. A new world becomes briefly, shiningly possible.

Song of the Reappeared is organized into three movements: a brief, intense first movement; a lyrical second movement that grows from an intimate beginning into vast, expansive musical vistas; and an energetic, righteously joyous finale.

The first movement, El mar (The Sea), begins with quick, darting gestures in the strings and clarinets, like tiny forms suspended in the sky, hovering, falling. An ominous, percussive pulse undergirds the swirling string texture. The soprano’s first words paint a frightening image: “Sorprendentes carnadas llueven del cielo” (“Strange baits rain from the sky”). This “bait” is the bodies of the disappeared, thrown from above into the ocean, reduced to mere fishmeal. In each movement, there is a moment when words fail and the orchestra must take over, and in the first movement, this section is a wild, writhing dance.

The lyrical, expansive middle movement, Una ruta en las soledades (A Path in the Solitudes), features the english horn as a co-soloist, whose long, songful lines engage in dialogue with the soprano’s. Zurita’s poetry here seems to be spoken by one of the dead addressing his beloved

The movement ends in an intimate, quiet atmosphere. Zurita’s speaker promises the person he loves that, in some world or other, they will be reunited: “And I will love you again. . . . And the flesh we were will cover us again like the mountains with living lava.”

The english horn traces a fleeting, evanescent figure, turning a corner and disappearing into nothingness.

If the first movement was a descent, the third and final movement, Rompientes (Breakers), is an ascension. This is music of return, restoration, and resurrection. The Pacific Ocean, with its ferocious, unceasing energy, becomes an emblem of unquenchable, ongoing life: “ . . . because the Pacific was resurrection and the breakers of resurrection beat and thrashed against the mountains.”

The music of this last movement is defiant and joyful. The speaker bears witness both to the horrors of the past (“because they threw us into the sea and the fish were the carnivorous tombs of the sea”) and also to the reality of an unstoppable, ongoing life force that emanates from the planet itself: “the breakers of resurrection glided above us.”

Music by Matthew Aucoin Based on Poems by Raúl Zurita

Sorprendentes carnadas llueven del cielo. Sorprendentes carnadas sobre el mar. Abajo el océano, arriba las inusitadas nubes de un día claro. Sorprendentes carnadas llueven sobre el mar. Hubo un amor que llueve, hubo un día claro que llueve ahora sobre el mar.

Oí un cielo y un mar alucinantes, oí soles estallados de amor cayendo como frutos, oí torbellinos de peces devorando las carnes rosa de sorprendentes carnadas.

Santo es el mar, santas las llanuras de frutos humanos que caen, santos los peces.

Oí infinitos días cayendo, cuerpos que caían con cielos . . .

La zarza del mar de Chile arde, arde sin consumirse.

Fueron arrojados. Como prendidos de extrañas semillas, campos arados cubren el mar.

Strange baits rain from the sky. Surprising bait falls upon the sea. Down below the ocean, up above unusual clouds on a clear day. Surprising baits rain on the sea. There was a love raining, there was a clear day that’s raining now on the sea.

I heard a sea and a sky hallucinated, I heard suns exploding with love fall like fruits, I heard whirlwinds of fish devouring the pink flesh of surprising baits.

The sea is holy, holy the wide plains of human fruits that fall, the fish holy.

I heard infinite days falling, bodies that fell with skies . . .

The bush that is the Chilean sea burns and does not burn up.

They were thrown. Heavy with strange seed, plowed fields cover the sea.

Así como las piedras hablan, así como la tierra habla, así yo te hablo. Y la ceguera de mis dedos hablándote recorren tu cráneo, tus narices, las fosas de tus ojos, y de bruces es el infinito del cielo . . . y entonces así, como las piedras hablan, como la tierra habla, yo te hablo cadáver de mí, amor de mí, huesos de mí, pequeña pupila redonda de todo el amor que sube y es el canto de los ojos de ti mirándome.

. . . y mi boca te dirá: te mataron y ahora vives. Y como el cielo, como la nieve, como un país de témpanos que nace tu boca me dirá: estabas muerto y hoy estás vivo.

¡Y te veo!

Y mirándome, y ciegos mirándome, y ciegos como entero el cielo mirándome, me ves subiendo, y me ves subiendo y subiendo, y tus ojos ven mis ojos llenos de tierra subiendo . . .

Y te amaré de nuevo. Y desde nuestras pupilas muertas se abrirán los cielos. . . . Y me mirarás, y me mirarás de nuevo. . . . Y las carnes que fuimos nos cubrirán de nuevo como de lava viva las montañas. . . . Y te amaré de nuevo.

. . . . Y se trazará una ruta en las soledades.

In the same way that the stones speak, that the earth speaks, I speak to you. And the blindness of my fingers speaks to you as they feel their way over your skull, your nose, your eye sockets, and the infinite sky has collapsed . . . and then, as the stones speak, as the earth speaks, I speak to you, corpse of me, love of me, bones of me, small round pupil of all the love that rises and is the song of your eyes looking at me.

. . . and my mouth will say to you: they killed you and now you are alive. And like the sky, like the snow, like a country of icebergs being born your mouth will say to me: you were dead and today you are alive.

And I see you!

And looking at me, blind and looking at me, and blind like the whole sky looking at me, you see me rising up, and you see me rising and rising and your eyes see my eyes full of earth rising . . .

And I will love you again. And from the dead pupils of our eyes the skies will open. . . . And you will look at me, and you will look at me again. . . . And the flesh we were will cover us again like the mountains with living lava. . . . And I will love you again.

. . . . And a path will be traced through the solitudes.

Hablemos entonces del vuelo del nuevo océano y de las rompientes en el cielo. De los cuerpos arrojados sobre los volcanes, ríos y lagos de Chile y que ahora son el mar y vuelven. Del amor del que fuimos asesinados y que ahora vuelve. De la vida que vuelve . . . de las carnes para peces que fuimos y del Pacífico porque era el Pacífico la resurrección, y las rompientes de la resurrección flotan en el cielo . . . y las rompientes de la resurrección aleteaban azotando las montañas.

Escuchen ahora las olas azotando las cumbres, las playas nuevas que no estaban contempladas porque las rompientes flotan sobre el cielo y son un mar.

Sí, porque tirados cielo abajo escuchamos el silencio de las rompientes y el estrépito de las enmudecidas rompientes batía huracanando las cordilleras igual que pastos bajo el viento. Y viento tras viento, pasto tras pasto, la aurora emergiendo del mar nos tiró los párpados secos. . . . Y las montañas mudas subían sobre las montañas. Y las rompientes mudas subían sobre las rompientes . . . y las caras y las espumas y la muerte se nos iban amontonando abajo como si una ola de luz se nos fuera a reventar cantando en los ojos.

Y entonces, llovidos desde feroces nubes nuestras pupilas vacías oyeron aletear las suspendidas rompientes. . . . Porque nos lanzaron al mar y los peces fueron las carnívoras tumbas del mar. Porque nos lanzaron a los volcanes y fueron los cráteres las carnívoras tumbas de las volcanes.

Sí, porque nos mataron y morimos y las rompientes de la resurrección nos volaban por arriba . . .

Text

by Raúl

Zurita

©

Raúl Zurita.

Used by kind permission

Let us speak then of the flight of the new ocean and of the breakers in the sky. Of bodies thrown out over the volcanoes, rivers, and lakes of Chile and that now are the sea and return. Of the love from which we were murdered and which now returns. Of the life which returns . . . of the meat for fish that we were and of the Pacific because the Pacific was resurrection, and the breakers of resurrection float in the sky . . . and the breakers of the resurrection beat and thrashed against the mountains.

Listen now to the waves thrashing against the peaks, the new beaches that had not been dreamt of because the breakers float over the sky and are a sea.

Yes, because thrown out of the sky we heard the silence of the breakers and the roar of the mute breakers beat like a hurricane against the cordilleras like wind on fields of grass. And wind upon wind, field upon field, the dawn emerging from the sea tore at our dry eyelids. . . . And the mute mountains rose up on top of the mountains. And the silent breakers rose upon the breakers . . . and faces and foam and death piled up beneath us as if a wave of light had broken and was singing in our eyes.

And then rained down from ferocious clouds our empty pupils heard the beating of the suspended breakers. . . . Because they threw us into the sea and the fish were the carnivorous tombs of the sea. Because they threw us into the volcanoes and the craters were the carnivorous tombs of the volcanoes.

Yes, because they killed us and we died and the breakers of resurrection glided above us . . .

English translation by William Rowe, New York Review of Books, 2018

RICHARD STRAUSS

Born June 11, 1864; Munich, Germany

Died September 8, 1949; Garmisch, Germany

Had Strauss’s first opera, Guntram, succeeded as he hoped, he surely would have gone ahead with his plan to make Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks his second. But Guntram was a major disappointment and Strauss reconsidered. We’ll never know what sort of opera Till Eulenspiegel might have been—the unfinished libretto isn’t promising—but as a tone poem it’s close to perfection.

The failure of Guntram hurt—Strauss wasn’t used to bad reviews or public indifference. Now, more than ever, he refused to give up on his hero, Till Eulenspiegel, an incorrigible prankster with a certain contempt for humanity, who sets out to get even with society. (There was a real Till Eulenspiegel who lived in the fourteenth century.) But Strauss was no longer certain that the opera stage was the best place to tell this story—“the figure of Master Till Eulenspiegel does not quite appear before my eyes,” he finally confessed—and he returned to the vehicle of his greatest past successes, the orchestral tone poem. Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks is arguably his greatest achievement in the form.

Ferruccio Busoni, the pioneering Italian composer, said that in Till Eulenspiegel Strauss reached a mastery of lightness and humor unrivaled in German music since Haydn. The humor wasn’t so surprising—although some listeners had found the deep seriousness of Death and Transfiguration, Strauss’s previous tone poem, worrisome—but to achieve such transparency with an orchestra of unparalleled size seemed miraculous.

At the time of the premiere of Till Eulenspiegel, Strauss resisted fitting a narrative to his music, but he later admitted a few points of reference. He begins by beckoning us to gather round, setting a warm “once-upon-a-time” mood into which the horn jumps with one of the most famous themes in all music— the daring, teasing, cartwheeling tune that characterizes this roguish hero better than any well-chosen words ever could. The

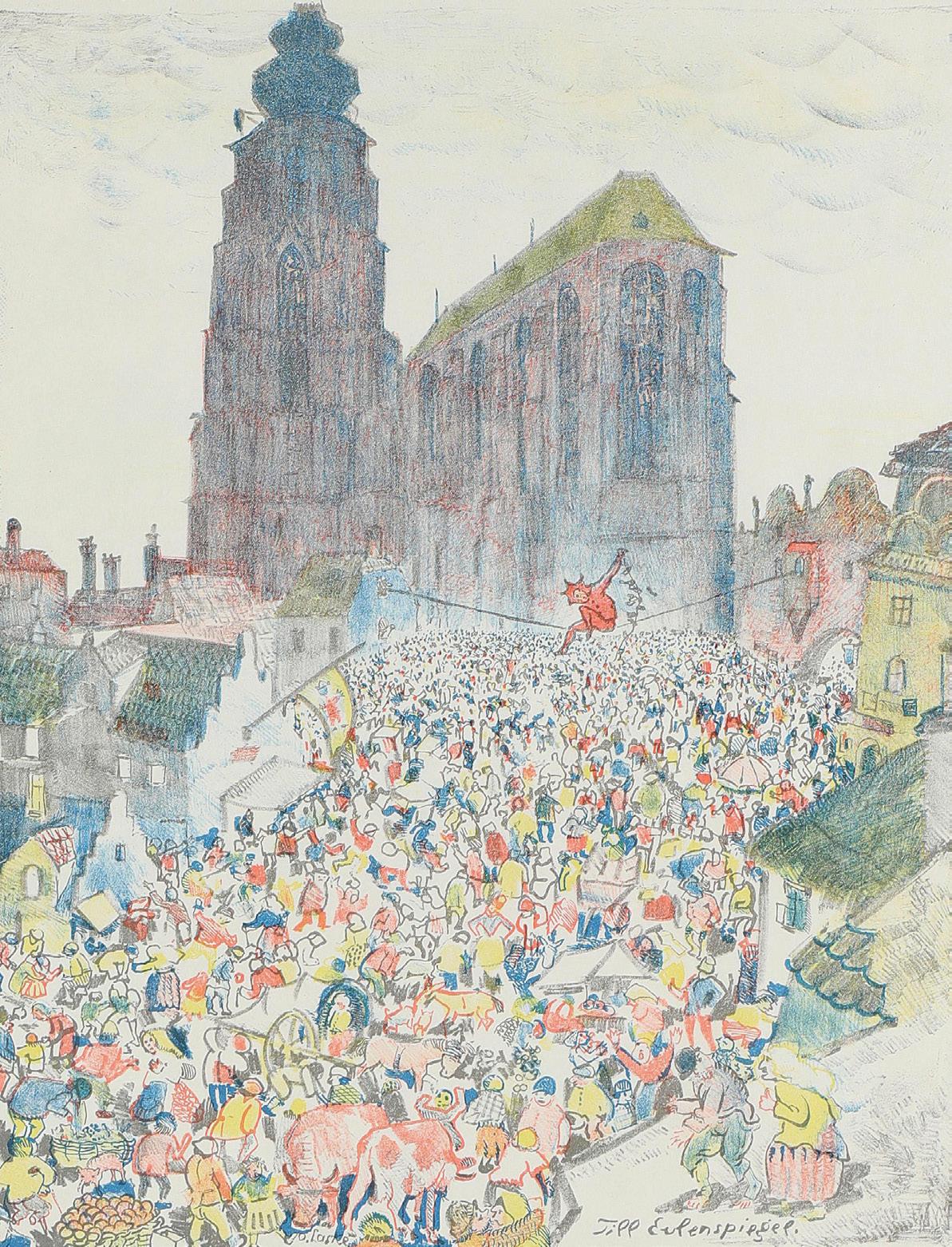

this page : Richard Strauss, cabinet photograph, 1894. Atelier Hertel, Weimar, Germany | opposite page : Till Eulenspiegel, lithograph by Viennese painter and printmaker Oskar Laske (1874–1951), 1935, showing the trickster suspended on a wire high above the crowd

COMPOSED 1894–95

FIRST PERFORMANCE

November 5, 1895; Cologne, Germany

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes and piccolo, 3 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, 3 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, large rattle, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 16 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 15 and 16, 1895, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting (U.S. premiere)

July 26, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Henry Weber conducting

CSO PERFORMANCES, THE COMPOSER CONDUCTING April 1 and 2, 1904, Auditorium Theatre

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 12, 2006, Ravinia Festival. Yoel Levi conducting

November 11, 12, 13, and 14, 2015, Orchestra Hall. Edo de Waart conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1940. Frederick Stock conducting. CSO (Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years)

1957. Fritz Reiner conducting. CSO (From the Archives, vol. 11: The Reiner Era II)

1975. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1977. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London (video)

1990. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Erato

1995. Pierre Boulez conducting. CSO (From the Archives, vol. 19: A Tribute to Pierre Boulez)

portrait is rounded off by the nose-thumbing pranks of the clarinet.

From there the music simply explodes, as the orchestra responds to Till’s every move. When he dons the frock of a priest, the music turns mock-serious; when he escapes, down a handy violin glissando, in search of love, Strauss supplies sumptuous string harmonies Don Juan would envy. Rejected in love, Till takes on academia, but his cavalier remarks and the professors’ ponderous deliberations (intoned by the bassoons and bass clarinet) find no common ground. Till departs with a Grosse Grimasse (Strauss’s term) that rattles the entire orchestra, and then slips out the back way, whistling as he goes.

After a quick review of recent escapades—a recapitulation of sorts—Till is brought before a jury (the pounding of the gavel is provided by the fff roll of the side drum). The judge’s repeated pronouncements do not quiet Till’s insolent remarks. But the death sentence— announced by the brass, falling the interval of a major seventh, the widest possible drop short of an octave—silences him for good. It’s over in a flash.

Then Strauss turns the page, draws us round him once again, and reminds us that this is only a tone poem. And with a smile, he closes the book.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

You can order drinks and snacks before the performance or during intermission at various bars located throughout Symphony Center, including the Bass Bar in the Rotunda and most of the lobby spaces in Orchestra Hall.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

March 1 and 2, 2024, Orchestra Hall. Mendelssohn’s The Hebrides Overture, Schubert’s Symphony no. 6, and Beethoven’s Symphony no. 7

Chief Conductor Petr Popelka’s 2025–26 season is underscored by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra’s 125th anniversary celebration with a gala concert in October followed by a European tour, which continues to Asia during the spring of 2026. In addition to performances at the Konzerthaus and Musikverein in Vienna, Popelka and the orchestra launch their second edition of the Primavera da Vienna Festival in Trieste following its success last season.

Further highlights of the season include Popelka’s debuts with the Berlin and Munich philharmonic orchestras and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, as well as his return to the Cleveland Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. With the Czech Philharmonic, he embarks on a summer tour to the Grafenegg and George Enescu festivals.

An acclaimed opera conductor, Petr Popelka led a new production of Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Die Fledermaus with the Vienna Symphony at the

Theater an der Wien in October. In addition, he conducts Puccini’s Tosca at the Berlin State Opera and returns to the Bavarian State Opera for Dvořák’s Rusalka during the 2026 Munich Opera Festival.

Previous debuts have taken him to the Staatskapelle Berlin, Staatskapelle Dresden, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, TonhalleOrchester Zürich, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, and the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Tokyo, among others. Last season, he was featured in such televised events as the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra’s Velvet Revolution concert and the 2024 Nobel Prize Concert with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra. He also made guest appearances at the Zurich Opera House (Mozart’s Don Giovanni), Bavarian State Opera (Janáček’s Káťa Kabanová), Deutsche Oper Berlin (Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde), Semperoper Dresden (Shostakovich’s The Nose), and Theater an der Wien (Weinberger’s Schwanda).

Petr Popelka began his conducting career during the 2019–20 season after serving as deputy principal double bass at the Staatskapelle Dresden from 2010 to 2019. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed chief conductor of the Norwegian Radio Orchestra in Oslo from 2020 to 2023 and now is also chief conductor of the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra since the 2022–23 season. He received his musical training in his hometown of Prague and in Freiburg, Germany.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCE

July 22, 2021, Ravinia Festival. Mahler’s Symphony no. 4, Marin Alsop conducting

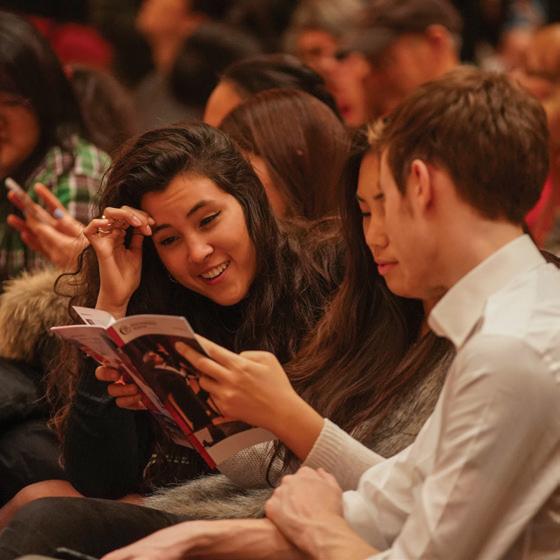

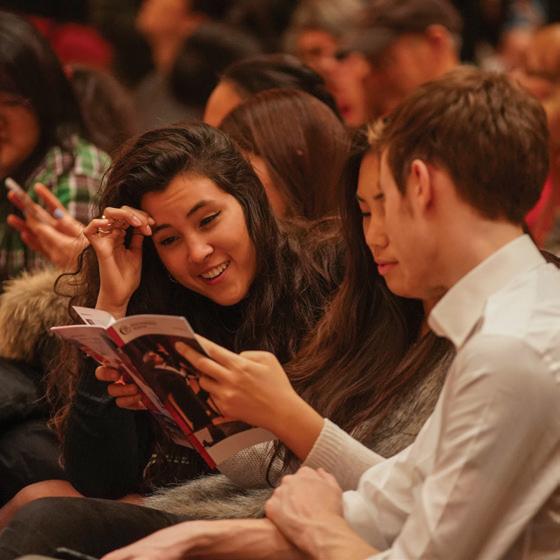

These concerts mark Julia Bullock’s subscription concert debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Grammy Award–winning

American classical singer

Julia Bullock, a prominent voice of social consciousness and activism, combines versatile artistry with a probing intellect and commanding stage presence. As well as headlining productions and concerts at preeminent arts institutions around the world, she has held positions as artist-in-residence of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Cal Performances in Berkeley, and the San Francisco Symphony.

Bullock’s career spans repertoire from the baroque canon to contemporary works written expressly for her. This season, she joins the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Petr Popelka for the world premiere of Song of the Reappeared, a song cycle commissioned by the CSO from Matthew Aucoin, who composed it for her, and sings Poulenc’s La voix humaine with the Gävle Symphony Orchestra and Christian Reif, her husband, in Sweden. She premieres a commission by Tania León on a U.S. recital tour, reprises signature projects at the Adelaide Festival in Australia, and curates the Cincinnati Symphony’s May Festival. Recent operatic highlights include headlining John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra and El Niño at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and creating important new roles in Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, Michel van der Aa’s Upload, and Adams’s Girls of the Golden West.

In concert, Bullock has performed with ensembles including the Los Angeles and New York philharmonic orchestras; the Baltimore, Boston, London, NHK Tokyo, and San Francisco symphony orchestras; the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; and the Philharmonia Orchestra and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in London. Past solo highlights include tours with the American Modern Opera Company, of which she is a founding core member; the American, British, Belgian, and Russian premieres of Zauberland; and recitals at Carnegie Hall in New York, Disney Hall in Los Angeles, the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, the Celebrity Series of Boston, the Kennedy Center in Washington (D.C.), and Wigmore Hall in London.

Bullock has developed and launched three signature projects, all flourishing nationally and beyond. Her multimedia ensemble program, History’s Persistent Voice, addresses the transatlantic slave trade through songs by people enslaved in the United States and through visual art, poetry, and new music by Black female composers. Devised with Reif, El Niño: Nativity Reconsidered is a chamber-orchestra arrangement of El Niño that amplifies the voices of women and Latin American poets. Perle Noire: Meditations for Joséphine, created with Tyshawn Sorey, Claudia Rankine, Michael Schumacher, and Peter Sellars, reexamines the life and legacy of Joséphine Baker. Bullock’s solo album debut, Walking in the Dark, recorded with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Reif for Nonesuch, won the 2024 Grammy Award for Best Classical Solo Vocal as well as Opus Klassik and Edison Klassiek awards. Her discography also includes Grammy-nominated recordings of Adams’s Doctor Atomic and Bernstein’s West Side Story, while other honors include the Sphinx Medal of Excellence, Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award, and first prize at the Naumburg International Vocal Competition.

The CSO Latino Alliance is a liaison and partner organization that connects the CSO with Chicago’s diverse communities by creating awareness, sharing insights and building relationships for generations to come. The group encourages individuals and their families to discover and experience timeless music with other enthusiasts in concerts, receptions and educational events.

Be a part of the season with concerts across musical genres highlighting world-class performances and compositions from Aida Cuevas, Sinfónica de Minería, Pablo Sáinz-Villegas, Gonzalo Rubalcaba and more!

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

The CSO African American Network aims to engage Chicago’s culturally rich African American community through the sharing and exchanging of unforgettable musical experiences while building relationships for generations to come. The AAN seeks to serve and encourage individuals, families, educators, students, musicians, composers and businesses to discover and experience the timeless beauty of music.

Be a part of the season with concerts across musical genres highlighting world-class performances and compositions from Christian McBride, Julia Bullock, Lizz Wright, Mike Reed, Wynton Marsalis and more!

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler

Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Olivia Jakyoung Huh

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation,

Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Access CSO program books and program notes online at cso.org/program. For most performances, notes are offered in written and video formats. Digital CSO program books are made possible with the generous support of The Walter and Karla Goldschmidt Foundation.

The Symphony Store

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery

Commemorate your trip to Orchestra Hall with exclusive CSO souvenirs. The Store is open before all CSO and select Symphony Center Presents concerts. Regular store hours are Tuesday–Saturday, 11:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Visit symphonystore.com to shop online.

Children: Children 8 years of age and older are welcome to attend concerts at Symphony Center. CSO for Kids and select holiday and film concerts are open to children 3 years of age and older. All children, regardless of age, must have their own tickets for all performances. CSO Family Matinee concerts are recommended for ages 5 and up; Once Upon a Symphony concerts are recommended for ages 3–5.

Late seating: Late seating is at the discretion of house management and may not be available for certain programs and seating locations. For most concerts, late seating opportunities are between pieces or at intermission.

Box Level seating: Box Level seats are unnumbered, and the tradition is to rotate seating either between works or at intermission.

Electronic devices: Cell phones, pagers and all other mobile devices must be turned off or silenced before entering Orchestra Hall. The use of such devices during the performance is not permitted. Photography and video recording are prohibited during the performance.

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

TRUSTEES

R. John Aalbregtse

Peter J. Barack

H. Rigel Barber

Randy Lamm Berlin

Merrill Blau*

Roderick Branch

Robert J. Buford

Johannes Burlin

Leslie Henner Burns

Marion A. Cameron-Gray

George P. Colis

Keith S. Crow

Stephen V. D’Amore

Timothy A. Duffy

Brian W. Duwe

James B. Fadim

Robert B. Ford

Matthew Fry*

Jennifer Amler Goldstein

Sarah Good*

Mary Louise Gorno

Graham C. Grady

John Holmes

Janice L. Honigberg

Lori Julian

Neil T. Kawashima

Geraldine Keefe

Donna L. Kendall

Thomas Kilroy

Dr. Randall S. Kroszner

Patty C. Lane

Jason M. Laurie

Ling Z. Markovitz

Renée Metcalf

Britt M. Miller

Frank B. Modruson

Toni-Marie Montgomery

Mary Pivirotto Murley

Sylvia Neil

Christopher A. O’Herlihy

Santa J. Ono

Gerald L. Pauling II

Andrew Pritzker

LTC. Jennifer N. Pritzker, USA (Ret.)

Katherine Protextor Drehkoff

Dr. Don M. Randel

Melissa M. Root

Burton X. Rosenberg

E. Scott Santi

Steven Shebik

Marlon R. Smith

Walter S. Snodell

Juan B. Solana*

Tracy A. Stanciel*

Dr. Eugene Stark

Daniel E. Sullivan, Jr.

Scott C. Swanson

Nasrin Thierer

Liisa M. Thomas

Christopher D. Tower

Laura Sumner Truax*

Frederick H. Waddell

Paul S. Watford

Craig R. Williams

Robert Wislow

Helen Zell

Gifford R. Zimmerman

LIFE TRUSTEES

William Adams IV

Mrs. Robert A. Beatty

Arnold M. Berlin

Laurence O. Booth

William G. Brown

Dean L. Buntrock

Bruce E. Clinton

Richard Colburn

Richard H. Cooper

Anthony T. Dean

John A. Edwardson

Thomas J. Eyerman

* Ex Officio Trustee † Deceased List as of November 2025

David W. Fox, Sr.

Cyrus F. Freidheim, Jr.

Mrs. Robert W. Galvin

Paul C. Gignilliat †

Joseph B. Glossberg

Richard C. Godfrey

William A. Goldstein

Chester A. Gougis

Mary Winton Green

David P. Hackett

Joan W. Harris

John H. Hart

Thomas C. Heagy

Jay L. Henderson

Debora de Hoyos

William R. Jentes

Richard B. Kapnick

Donald G. Kempf, Jr.

Mrs. John C. Kern

Robert Kohl

Josef Lakonishok

Charles Ashby Lewis

Eva F. Lichtenberg

John F. Manley

R. Eden Martin

Arthur C. Martinez

Judith W. McCue

Lester H. McKeever Jr.

David E. McNeel

William A. Osborn

Mrs. Albert Pawlick

Jane DiRenzo Pigott

John M. Pratt

Dr. Irwin Press

John W. Rogers, Jr.

Jerry Rose

Frank A. Rossi

John R. Schmidt

Thomas C. Sheffield, Jr.

Robert C. Spoerri

Carl W. Stern

William H. Strong

Louis C. Sudler, Jr. †

Richard L. Thomas

Richard P. Toft

Penny Van Horn

Paul R. Wiggin

Jeff Alexander President

PRESIDENT’S OFFICE

Kristine Stassen Executive Assistant to the President & Secretary of the Board

Mónica Lugo Executive Assistant to the Music Director Emeritus for Life

Human Resources

Lynne Sorkin Director

Dijana Cirkic Manager

ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATION

Cristina Rocca Vice President

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

James M. Fahey Senior Director, Programming, Symphony Center Presents

Randy Elliot Director, Artistic Administration

Monica Wentz Director, Artistic Planning & Special Projects

Lena Breitkreuz Artist Manager, Symphony Center Presents

Jackson Brown Artistic Planning Coordinator

Caroline Eichler Senior Artist Liaison, CSO

Phillip Huscher Scholar-in-Residence & Program Annotator

Pietro Fiumara Artists Assistant

Chorus

Melissa Hilker Manager

Olive Haugh Assistant Manager & Librarian

ORCHESTRA AND BUILDING OPERATIONS

Vanessa Moss Vice President

Jiwon Sun Director, Tour & Media Operations

Michael Lavin Director of Production

Jeffrey Stang Associate Director of Production, CSO

Joseph Sherman Associate Director of Production, SCP & Rental Events

Jenise Sheppard House Manager

Charlie Post Chief Recording Engineer

Logan Goulart Production Coordinator

Sara Hedberg Operations Assistant

Rosenthal Archives

Frank Villella Director

Orchestra Personnel

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions & Orchestra Personnel

Facilities

John Maas Director

Engineers

Tim McElligott Chief Engineer

Michael McGeehan

Kevin Walsh

Stephen Excellent

Electricians

Robert Stokas Chief Electrician

Doug Scheuller

Stage Technicians

Christopher Lewis Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

AT THE CSO

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director

Katy Clusen Associate Director, CSO for Kids

Katherine Eaton Coordinator, School Partnerships

Carol Kelleher Assistant, CSO for Kids

Anna Perkins Orchestra Manager, Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Zhiqian Wu Operations Coordinator, Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Rachael Cohen Program Manager

Charles Jones Program Assistant

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer

Renay Johansen Slifka Executive Assistant

Accounting

Sam Pincich Controller

Kerri Gravlin Director, Financial Planning & Analysis

Hyon Yu Assistant Controller, Reporting & Systems

Janet Kosiba Assistant Controller, Accounting Operations

Mehrin Reid Payroll Manager

Karen Levin Accounting Manager

Milda Reklyte Senior Accountant

Christopher Biemer Accountant

Cynthia Maday Accounts Payable Manager

Elizabeth Tyska Payroll Assistant

Information Technology

Kirk McMahon Director

Douglas Bolino Client Systems Administrator

Jackie Spark Lead Technologist

Dwayne Laughlin Tessitura Systems AnalystTechnologist

Ryan Lewis Vice President

Erika Nelson Director, Institutional Marketing & Revenue Management

Alyssa Greenberg Manager, Audience Engagement

Digital Content and Engagement

Dana Navarro Director

Laura Emerick Digital Content Editor

Peter Breithaupt Manager, Digital Content

Steve Burkholder Web Manager

Megan Ireland Manager, Digital Engagement

Zoe Carter Associate, Digital Engagement: Social Media

Program Marketing and Operations

Amy Brondyke Director

Alex Demas Marketing Manager, Classical Programs

Tommy Crawford Marketing Manager, Jazz, World & Popular Programs

Kate McDuffie Manager, Community & Family Programs

Jessica Reinhart Advertising & Promotions Manager

Amanda Swanson Marketing Analyst

Jesse Bruer Marketing & Promotions Associate

Andrew Hilgendorf Email Marketing Associate

Creative

Jaime Hotz Director

Sophie Weber Associate Director, Project &

Digital Asset Management

Emily Herrington Lead Designer

Fattah Mulya Design Associate

Communications

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Frances Atkins Director, Publications & Institutional Content

Gerald Virgil Senior Content Editor

Kristin Tobin Designer & Print

Production Manager

Media Relations

Hannah Sundwall Director

Clay Baker Manager

Sales and Patron Experience

Joseph Fernicola III Director

Pavan Singh Manager, Patron Services

Brian Koenig Manager, Preferred Services

Joseph Garnett Senior Manager, Box Office

Nicholas Bryan, Aislinn Gagliardi Assistant Managers, Patron Services

Justin Corp, Carmen Ringhiser Assistant Managers, Preferred Services

The Symphony Store

Tyler Holstrom Manager

Annie Grapentine Assistant Manager

Dale Hedding Vice President

Jeremiah Strickler Manager, Development Administration

Allison Szafranski Director, Leadership Gifts

John Heffernan, Tori Ramsay

Major Gifts Officers

Karen Bippus Director, Endowment Gifts & Planned Giving

Kevin Gupana Associate Director, Education & Community Engagement Giving

Victoria Barbarji Associate Director, Campaigns & Strategic Giving

Joe Bauer Manager, Endowment Gifts & Planned Giving

Institutional Advancement

Susan Green Director, Foundation & Government Relations

Nick Magnone Director, Corporate Development

Mary Grace Corrigan Manager, Grants & Institutional Giving

Donor Engagement and Development Operations

Liz Heinitz Senior Director, Development

Lisa McDaniel Director, Donor Engagement

Alyssa Hagen Associate Director, Donor & Development Services

Kimberly Duffy Associate Director, Donor Engagement

Jocelyn Weberg Senior Manager, Annual Giving

Jamie Forssander, Brent Taghap Managers, Donor Engagement

Jeremiah Pickett III Manager, Governing Member Gifts

Hope Oester Prospect & Donor Research Specialist

Mykele Callicutt Coordinator, Donor Engagement

Victoria Menendez, Elisabeth Miller

Coordinators, Donor Services

Casey Bowman Coordinator, Development Communications

MAR 5-6

Mäkelä Conducts The Rite of Spring

APR 16-18

Evgeny Kissin with the CSO

APR 23-26

Hisaishi Conducts Hisaishi

MAY 12

Samara Joy & the CSO

JUNE 23