14 minute read

Containers Rebecca Bevan offers

Contain Your EXCITEMENT

Rebecca Bevan distils 300 years of experience from Britain’s finest gardens in her new book, The National Trust School of Gardening, including advice on creating glorious seasonal container displays

Glossy aeoniums and scarlet pelargoniums brighten summer containers in the garden at Hidcote.

Above Pots line up along the wall in Bodnant’s poolside garden, which is known as The Bath. H owever nice your pots, the plants should be the stars of the show. The general rule is to ensure that the plant mass is always as big or bigger than the container. Most small spaces look better with one large pot with a decent specimen plant, rather than small pots dotted about, which can get rather lost. Bigger pots will also dry out less quickly if you are away over a sunny weekend and can’t water them. If you have only small pots, grouping them into collections can create the sense of mass needed to make an impact. The advantage of this is that individual pots can be moved into the display when at their best and hidden when the plants go over.

The affordability and temporariness of bedding plants makes it easy to experiment with new combinations each year. Some gardeners aim to create schemes that harmonise with nearby borders. For others, seasonal container displays are an opportunity to introduce new colours and textures to change the look of an area. A striking effect for a terrace or balcony is to fill a number of pots with

CONTAINER IDEAS from Tintinhull

Senior Gardener Helena Hewson plants pots with a nod to Tintinhull’s creator, Phyllis Reiss

A brilliant welcome

Either side of the steps leading to the front door, Helena has grouped pots of varying sizes filled with a mix of different plants. Her favourites include clear-blue, daisy-flowered Felicia amelloides, an old-fashioned but reliable plant that Phyllis Reiss would almost certainly have grown, and Salvia discolor, a more adventurous choice with silver leaves and jet-black flowers. Towering above these are two Tibouchina urvilleana.

Scent and sensibility

Helena recommends scented-leaved pelargoniums for growing in pots: they are tolerant of heat and drought and irresistibly tactile. She and her team of volunteers propagate all their own pelargoniums from a collection that they keep in the greenhouse. They take cuttings in September and again in spring, if needed.

Hot spot

Helena plants large stone and terracotta pots with Canna indica, Helichrysum petiolare and Pelargonium ‘Shottesham Pet’. All three are tolerant of this hot, sunny site and the luxuriant canna foliage looks great against the stone.

The golden touch

Copper and gold Heucherella ‘Brass Lantern’, golden-leaved Carex oshimensis ‘Evergold’ and single-flowered Dahlia ‘Bishop of Dover’ perfectly complement the honeycoloured hamstone of the house wall.

Muted brilliance

In the Pool Garden – an iconic Tintinhull feature that Reiss designed as a memorial to her nephew – Helena plants four giant pots with purple-leaved cannas, Salvia cacaliifolia, pelargoniums and Helichrysum petiolare. She chooses not to use bright colours here as there is already enough drama from the famous hot and cool borders.

the same selection of Left A blue-glazed pot bedding plants so that complements these tiled together they form a collection. You don’t steps, helping to create a vivid Moroccan theme. Below A collection of need exactly the same pots grouped together combination in each makes real impact on pot, but some repetition this decking. between them will draw the eye from one to another and feel harmonious.

Most of us want our pots bursting with colour, but bold flowers close together can easily clash. To overcome this, choose complementary colours such as pastels, which always go well together, and aim for a mix of different flower shapes with some plants chosen purely for their foliage – many bedding plants have fabulous silver, gold, lime-green or glossy leaves. It’s also best to choose a mix of plants of different heights and habits. Many species used for bedding – including pelargoniums, verbenas and lobelias – are available in upright, spreading, semitrailing or fully trailing forms, so check when you are buying. Plants that trail elegantly are especially important for hanging baskets and window boxes.

Many shrubs, perennials and grasses also have a place in containers. Some of the longest flowering include everlasting wallflowers, dwarf penstemons and shrubby salvias. Mix them with bedding plants in large containers or provide them with containers of their own to stand among pots of bedding.

Most will need annual Right A grouping of repotting into fresh compost and regular containers at The Courts Garden in Wiltshire includes pelargoniums liquid feeds. Perennials and aeoniums. suited to container growing that need less frequent repotting and feeding include lavender and rosemary (which love sun and tolerate drought), hostas (which can be kept far more slug-free in pots than in the ground) and agapanthus (which flowers best when squeezed into a container). Exotics with dramatic foliage such as cannas, aeoniums and Melianthus major are effective surrounded by floriferous bedding.

Fill your pots three-quarters full with peat-free compost. A multipurpose one is suitable for all bedding plants. Shrubs and perennials planted in a pot for a few years do better in loam-based compost that will retain its structure for longer. Don’t reuse compost for seasonal displays – it won’t have enough nutrients left and is better spread on beds as a soil improver. For spring planting, some gardeners mix in a slow- or controlled-release fertiliser, but if you don’t want to buy another product, there’s no need: compost has plenty of nutrients and you can add more from organic liquid fertiliser during the summer. n

Adapted from The National Trust School of Gardening by Rebecca Bevan, £20, National Trust Books.

Trailing bedding plants for containers

Include some elegantly trailing foliage or flowers to cascade from the edges of your pots

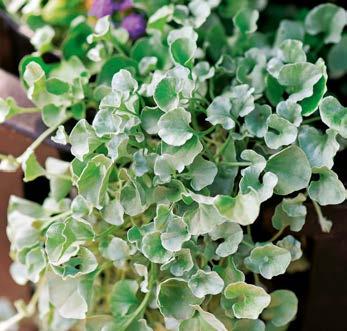

DICHONDRA ‘Silver Falls’ is a droughttolerant plant with delicate, shiny, brilliant silver leaves, which trails elegantly. PELARGONIUM Ivy-leaved geraniums are a classic trailing plant, available in many different colours and forms. PETUNIA The Surfinia Series is a range of reliable, cascading petunias often simply referred to as ‘surfinias’.

Preserving flowers through pressing or other means is a way to cherish prized specimens.

Still Life

Whether you are making a scientific botanical record, preserving memories or simply creating beautiful art, the techniques and ideas behind pressing flowers and making herbaria are easy to learn and apply

Above Equipment used for the herbarium at RHS Wisley includes colour charts that ensure ornamental hybrids are described accurately. W hen Philip Miller, chief gardener of the Chelsea Physic Garden, collected a sample of Lavandula x intermedia subsp. intermedia in the summer of 1731, he could scarcely have imagined it would still be in a collection some 300 years later. Yet today, pressed and labelled, Miller’s specimen is the oldest entry in the herbarium collection at RHS Wisley. What’s more, Lavandula x intermedia is widely grown today, being especially good for oil extraction. In this lies the brilliance of preserved flowers and herbaria specifically: they provide a window on the past and help us consider what the future might look like. With about 90,000 pressed plant species, the herbarium at RHS Wisley is not the largest in the UK but it is unique. “RHS Wisley’s is special because it contains only cultivated or ornamental plants,” explains keeper Yvette Harvey. “There are around 400,000 ornamental plants being grown in the UK and we intend to acquire as many of these as possible. We’re actively increasing the collection.” Established in 1916 with a bequest from the Reverend George Henslow, erstwhile lecturer in Botany at St Bart’s medical school and honorary professor of Botany to the RHS, early this year the collection moved into a brand new, state-of-the-art building, Hilltop, which is intended to open to the public later this year. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of these studious spaces sequestered from throngs of visitors and crowd-pleasing herbaceous borders yet so integral them. In 17th-century Bologna, Luca Ghini decided it was better in winter to refer to pressed flowers rather than drawings and established the first herbarium as a teaching aid. Since then, herbaria have provided the benchmark for species identification. There are now roughly 3,000 herbaria around the world collectively housing 300 million specimens. At RBG Kew, where total acquisitions number between seven and eight million – the full number will become known when digitisation is complete – the herbarium is the ultimate point of reference at the institution. For example, any seed entering the Millennium Seed Bank must also have a full pressed entry in the herbarium. “We have between 25,000 and 30,000 incoming specimens in an average year,” explains Nina Davies, senior curator of the herbarium at Kew. “The specimens come from all over the world, depending on the projects we’re running at the time. The list of uses of the herbarium is endless but mainly this is a collections-based research facility. Staff and visitors from across the world use the collections to classify plants for taxonomy but also for other things. Digitising specimens opens up opportunities for new research and can be used by anyone looking for information: students, historians, ethnobotanists, researchers, artists… We have around 400 visitors a year from all over the world and if you look at the history of the British Empire and of Kew, you can see why we have so many enquiries.”

On a somewhat more domestic scale at Wisley, Yvette points to the close relationship the RHS enjoys with Plant Heritage, the umbrella body for all the National Collection holders. Every holder of a plant collection must submit a selection to the RHS. This is a way of making sure that there is a record impervious to the whims of fashions and markets that can render certain varieties all but extinct. “The collection holders are so knowledgeable about their plants and, crucially, they know the provenance of their plants, something that is extremely important for us,” Yvette says.

The RHS herbarium is also a keeper of nomenclatural standards and is the definitive reference in terms of interpreting the name of a cultivar and providing notes on colour. It is an essential resource in compiling the ever-popular RHS Plant Finder. “Our molecular biologist uses plant DNA to look at the relationships between taxa,” says Yvette. This can be useful in wideranging scenarios, including settling court disputes between plant breeders. “The herbarium also helps botanists working in ecosystems services by helping to determine invasive species,” she adds.

Top There are around 400 visitors to the extensive herbarium at RBG Kew every year. Above right A passiflora specimen at RBG Kew. Above left Neat rows of archive boxes stored at Hilltop, the new RHS herbarium at Wisley.

This image Helichrysum bracteatum lends itself to lasting displays. Right Consider keeping a journal using favourite pressed flowers. Below Flower-pressing equipment.

Start a personal collection

Herbaria are by no means the exclusive domain of institutions. There is nothing to stop you beginning your own modest herbarium, and both Nina and Yvette point to the value of specific regional herbaria. “A personal herbarium could certainly become a resource for preserving UK plants, but it’s important to record whether the plant is wild or cultivated,” says Nina.

While herbaria are grounded in science, they can also be extraordinarily intimate. Nina enjoys the labels that accompany each preserved specimen. These contain as much information about the plant as possible, as well as where, when and by whom it was collected, but they are also a snapshot in time. “I always like thinking about what was happening in the world when the plant was collected,” Nina reflects. In this, even simply pressing or drying flowers, or collecting seed, is a meaningful way to record an event such as a birthday or wedding, a summer to go down in the annals, or the last season in a garden tended over a lifetime.

Pressing flowers was popular among Victorian women who compiled exsiccata – volumes of pressed plant specimens arranged to a theme. Kew’s collection of these volumes dates from the 18th century, and it has at least one distinctive entry. Writer Marion Adams-Acton (1846-1928), in addition to walking from London to Arran over seven weeks with a nurse and six children, including a baby in a pram (Adventures of a Perambulator, 1894), compiled a red velvet-bound volume entitled Art and Nature. The book’s provenance is uncertain, but from the plants it contains, it is believed AdamsActon assembled it during a summer on Arran.

Above Selected framed, pressed flowers by London-based JamJar Edit (jamjaredit.co.uk)

Further reading

Carolyn Dunster explores ways to preserve and present special flowers in Cut and Dry (£17.99, Laurence King). These include drying methods and allied techniques including growing ‘dry’ flowers such as Helichrysum bracteatum, making pot-pourri and displays under glass.

Preserving flowers has become increasingly popular. Few know this more than Amy Fielding of JamJar Edit, a fashionable outlet of pressed flowers and dried arrangements. Amy has collected and pressed flowers from the Dartmoor garden of a private client, but she’s also worked closely with Sketch restaurant in Mayfair. Special arrangements stem from JamJar Edit’s desire for sustainability: instead of throwing out leftover flowers, they’re hung upside down to dry. Workshops are perennially popular with a younger crowd. “We’ve all got a bit obsessed with our screens and going at a hundred miles an hour. People who come to our workshops just want to slow down and flower pressing forces you to do that. It’s a slow process, but it’s a beautiful thing to do,” she says. Amy points out that you don’t need more than a balcony to grow flowers to press, an appealing aspect of the pastime for city-dwellers. “There was this fusty Victorian image but it’s not that anymore. It’s wonderful and cool.” n

Press flowers like a pro

For the press Cut two pieces of board or finely corrugated card. The RHS size is 26.5cm by 42cm. Two cake-cooling racks and a tabloid newspaper opened out will do the job of a board. In the same size cut two pieces of 2cm-thick foam, four pieces of blotting paper, and two pieces of pH neutral parchment, called a flimsy, which will be in contact with the plant.

Method 1 On the label note the plant name, whether it’s cultivated or wild, location, collection date and plant size. Colour is important in cultivated plants, and the RHS uses a unique colour chart. “We take the specimen to a north-facing window, so the light is always the same. We look at the colours of the stems, leaves and the different shades of flowers,” says Yvette. 2 Place the floral parts on the bottom flimsy, fixing the leaves so one front and one back is pressed. Pull apart one flower and lay the individual parts. Cover with the top flimsy and blotting paper. 3 Dampen the top blotter with a mist spray. Place the foam and board on top, doing the same in reverse beneath. Tighten press straps: use webbing, string or elastic bands. 4 Place in an airing cupboard for 24 hours then replace the foam with a piece of blotter to continue drying. Remove after three days.

To Finish Mount onto 220gsm-240gsm acid-free paper. Brush acid-free PVA onto a sheet of newspaper. Press the specimen and the label onto the glue then transfer to the archival paper. Use too little glue and the edges will crinkle, too much and it will press out from the sides or wrinkle the paper. Cover the specimen with a sheet of wax paper then flatten it with your hand or rolling pin. Use a small bag of gravel to weight the specimen if needed and leave to dry. Secure any thick stems with a stitch through the paper.