8 minute read

Tom Cunli e

How the wisdom of an ancient mariner has ensured the minimum of damage when it comes to close quarters handling in a marina

Back in the days when boats still leaked and electronics weren’t even a glimmer in the sunrise, I learned many a useful lesson from the foreman at the Elephant Boatyard up the Hamble River. e late, great

Davey Elliot was a classic Solent longshoreman of the old school. I really don’t think there was anything about boats he didn’t know, but his talents reached far wider. He was an accomplished student of the human condition, he had a tongue that would split solid oak to take down any upstart sailor who fancied himself, and he was a natural healer. is latter gi was kept private and I had no inkling of it until one day, su ering more than usual from a cartilage injury, I was limping back to my boat from a trip to the skip when he called over to me.

“Looks like you’ve got a problem with your knee, Nipper,” he said. Although I was then pushing 50, he’d called me that ever since I was a 6 6in 22-year-old struggling with my rst wooden boat.

“Come on over to my emporium and I’ll see what I can do.”

Not knowing what to expect, I tottered across to the shipping container where he kept his tools and work bench. Few of us on the yard were ever invited into this sanctus sanctorum, so I must have been doing something right. What

PODCAST

Catch up with Tom’s columns now and in the future at sailingtoday.co.uk

I recall best is the wonderful scent of the place. Fresh wood shavings mixed with Stockholm tar blended with linseed oil made a heady whi , while dri ing over it all was the pale blue fug of Davey’s pipe, which was rarely seen out of his mouth. At the end farthest from the door stood his well-worn sea chest, dating from his time as a ship’s carpenter going deep-sea. He sat me down on this and sized me up. We’d known each other for a quarter of a century. Although I was never a natural with caulking irons, saw and chisel, I like to think he had developed a sort of respect for me as an honest tryer who did at least make a habit of disappearing over the horizon and returning with a few tales to tell.

Davey didn’t say anything. He just held his cupped hands around my knee and seemed to go o into some sort of trance. He wasn’t touching me at all, but a er half a minute or so, my knee began to heat up. is was no illusion. It was pulsing with warmth and, a er a little while, he pulled his hands back as though they were being burned.

“ at’s enough for now,” he said, shaking his wrists. “It’s too hot for me. Must be doing some good. Come back tomorrow at ve o’clock when I knock o . We’ll give it some more.” And with that, he shooed me out, locked up the container and strolled back to the gangway of the traditional shing boat where he lived.

My knee felt better in the morning, and at 1700 I came back into the yard to report for treatment. Davey didn’t show up, so I waited until six o’clock then went to the pub next door for a refresher. In the bar I fell in with a neighbour from the yard. He looked sick and I was about to tell him that Davey hadn’t appeared, which was out of character, when he broke the news that my old friend had literally dropped dead that a ernoon.

Several pints later, more of Davey’s acolytes had gathered at the bar. Still in a state of disbelief, we remembered his sayings, his cuttingo of fools, and the kindness he was always ready to show to decent folk in need of a leg up. One incident had stuck rmly in my own mind and it will be there until I join Davey in the big shipyard down the far blue yonder. I was a young skipper in charge of a yacht with a heavy tonnage and a very large turning circle. One grey morning, the river was quiet, the tide slack and I was manoeuvring among moored yachts under power. I had to turn my boat through 180 degrees and, rather than opting for the prudent method of going ahead and astern, using the prop-walk to make the most of the small amount of space available, I decided to go for an all-or-nothing turn under full power with the rudder hard over. e propeller was bang in front of a large rudder. With lots of grunt coming o the prop, the blade diverted the gushing water, allowing me to swing round a lot more tightly than the yacht’s natural inclination. All was going ne. I was halfway through the manoeuvre and heading brie y towards a row of yachts secured fore-and a on a series of piles when the engine coughed and gave up the ghost. e silence was deafening but the heavy yacht hardly broke her stride. She kept right on going, but bere of her mighty propeller it was soon obvious that rather than get comfortably round, she was going to tee-bone one of the yachts on the trots ahead. I was leaning all my weight on the big tiller with

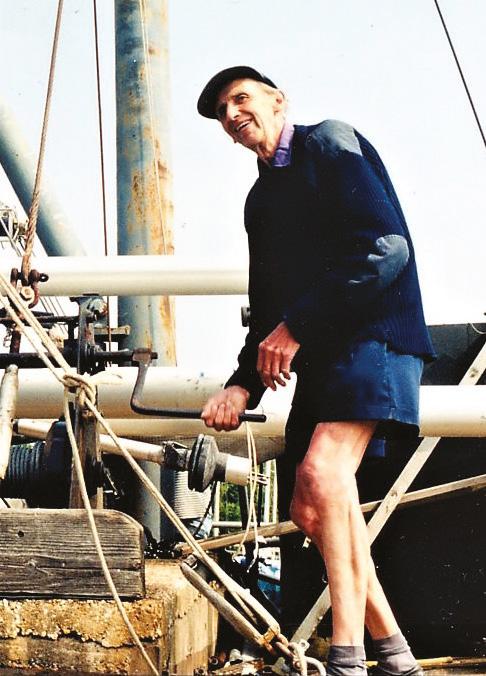

ABOVE

e late, great Davey Elliot

BELOW

Slipping into a simple berth. Would it were always so easy!

disaster looming and no clue about what to do next when Davey appeared in the companionway of the lovely varnished hull that was plumb in my sights. Taking his pipe calmly from his lips he pointed it to the gap between his long counter stern and the pile to which it was secured with a very large rope. Steering into this dubious haven was a possibility, because it involved easing the tiller. In any case, nobody with any sense of emotional survival argued with Davey, so I did as I was told. As the spoon bow of my long-keeled yacht rode up on Davey’s stern line he whipped a couple of turns o the bollard to which it was secured and expertly surged it away. Somehow, he gauged the friction just right and shrugged o the last of my way just before I hit anything. As the boats slowly came together with no damage at all, the cockpits fell alongside one another and he looked me square in the eye.

“Next time you’re heading for a line of yachts, Nipper,” he

ABOVE

A heady cocktail of tangled ropes, no fenders, confused crew and bemused onlookers – Davey would not have been impressed

TOM CUNLIFFE

Tom has been mate on a merchant ship, run yachts for gentlemen, operated charter boats, delivered, raced and taught. He writes the pilot for the English Channel, a complete set of cruising text books and runs his own internet club for sailors worldwide at tomcunli e.com said, re-lighting his pipe with much sucking and pu ng, “you be sure to pick a cheap one!”

I think about this incident every week as folk ask me to help with their sailing problems. Looking back on my own career I realise it’s no coincidence that the most popular questions are about manoeuvring under power. Speci cally, how the devil to get in and out of a tideswept nger berth hemmed in by ranks of pontoons sited far too close, and for which the annual fee would buy a respectable used car. Much is written in magazines about sure- re ways of defusing these horrors. Some of them work some of the time, but the bottom line is that there is o en no easy answer. I always advise marina visitors to tell the berthing master when they call up that they have an awkward boat, that they are inexperienced – whether they are or not – and that they really need an up-tide berth. Sending people into a down-tide cul-de-sac with the wind up their chu with a nal tight turn against the propeller is handing them a ticket to nowhere. We must insist on better service, but if there’s no help for it and you’re stuck with a non-starter, it’s a good idea to rig fenders on both sides, remember to keep up-tide when approaching along a pontoon corridor, take your time and work out what’s the most wretched result that can happen if it all goes belly-up. Be prepared for that while hoping for the best,_ and you’re a lot better o than the chancer who comes zooming in with no contingency plan, no fenders rigged and a foredeck crew still trying to untangle a line that’s too short anyway.

While you’re at it, look hard at any potential victims, price them up quickly and make sure you land up on the cheapest. You may not get your knee xed, but you can award yourself a wry chuckle at the end of the day.