6 minute read

Mind readers

Words by MICA BALE

We investigate the Edinburgh evolution of the pseudoscience phrenology, in which physicians believed they could tell the true character of a person by studying their skull

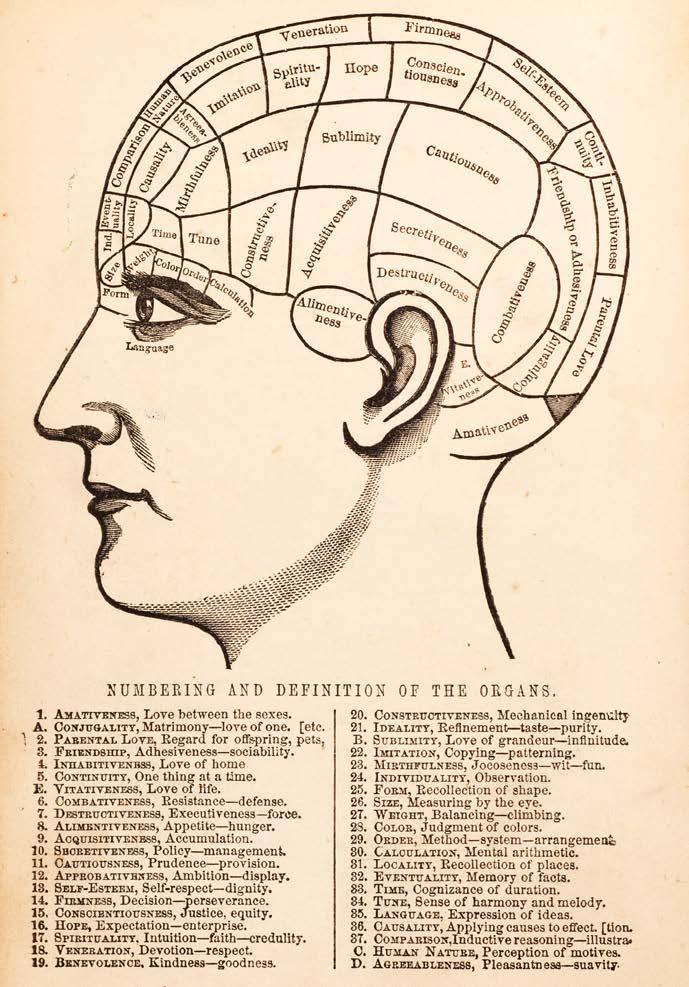

TOP LEFT:

A phrenology head was used to identify an individual’s character traits

TOP RIGHT:

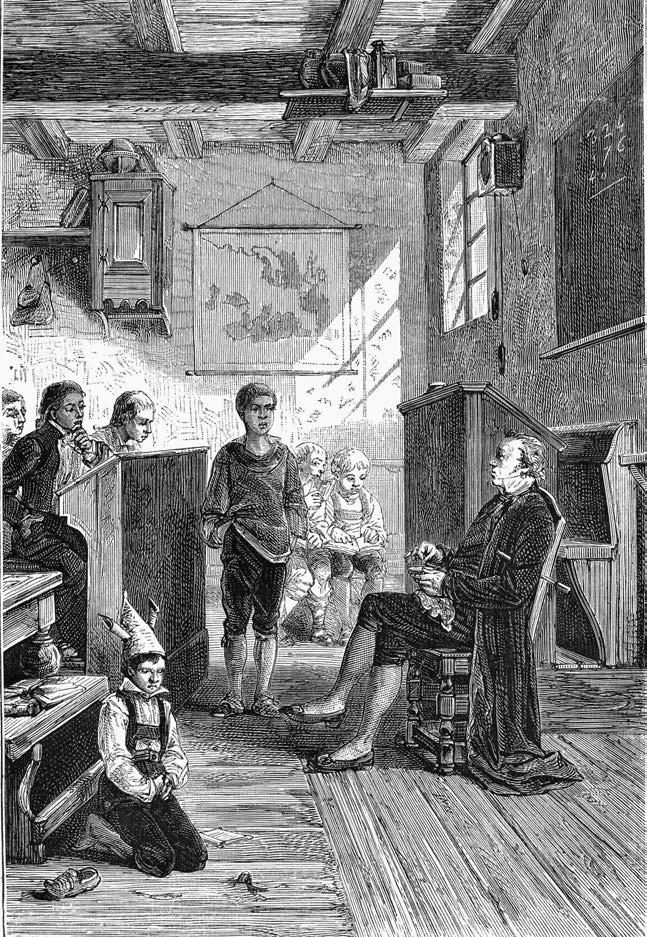

A wood engraving depicting Franz Joseph Gall (17581828), the German neuroanatomist whose theory of phrenology was allegedly inspired by a visit to a school in Tiefenbronn, Germany in c.1800 For modern-day thinkers, it’s a bit of a stretch to think that the shape and size of a human skull, a minute study of every bump and bulge, could determine the very essence of a person from their personality traits to the likelihood that they would become a criminal. However, in the late Georgian and early Victorian eras this was exactly what many people believed.

Though the idea of phrenology originated with German neuroanatomist Franz Joseph Gall, it was two Scottish brothers, George and Andrew Combe, who made phrenology especially popular in the British Isles, and who played instrumental roles in the formation of the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820. The Edinburgh Phrenological Society was the first of many organisations that sought to practice this new and exciting science and encourage leading medical professionals and, of course, the public to adopt their understanding.

Gall believed that the brain consisted of a total of 27 different organs and each of these subsections highlighted different character traits, from constructiveness to destructiveness, veneration to sublimity.

It is noteworthy that George Combe was a strong critic of the approach, initially. He was not a medical man, but a lawyer by occupation, and it was his brother, Andrew, who was the physician. In fact, a damning report in the Edinburgh Review regarding phrenology prompted Johann Spurzheim, a former assistant of Gall’s, to set out to the Scottish capital in person to prove the accuracy of phrenology via dissections.

ABOVE:

The building of the former Edinburgh Phrenological Society’s museum on Chambers Street still bears sculptures of George Combe and his contemporaries LEFT: Chambers Street in Edinburgh

After attending one such dissection by Spurzheim, George Combe began to embrace phrenology and he was among many others to do so. Medical professionals such as influential asylum doctor William AF Browne and pioneering neurophysiologist Thomas Laycock joined and enveloped the Edinburgh Phrenological Society with the respect and veneration it needed to gain the approval of the public.

George Combe was certainly not the sort of man to half-heartedly embrace anything and, once he was convinced of the accuracy of phrenology, he worked tirelessly to bring this field to the masses in Scotland and by extension Britain, before he then turned his focus to reaching out to Europe and the Americas.

Combe published journals, encouraged new members and professionals to join the society and even opened a museum that housed the now large collection of different medical artefacts that supported the theories behind phrenology.

This museum was located in Chambers Street in the city and, although it is no longer there, the Anatomical Museum at the University of Edinburgh maintains and exhibits many of the original artefacts from the museum.

Notorious criminals, particularly murderers, and local offenders were often sent to the neighbourhood’s phrenologist, and executions resulted in post-mortem ‘death masks’ being taken in an attempt to understand the mind behind the crime.

Dominic Hall, curator of the Warren Anatomical Museum at the Center for the History of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, says, “When I consider phrenology’s impact, I think mostly about the movements it enabled. While the science

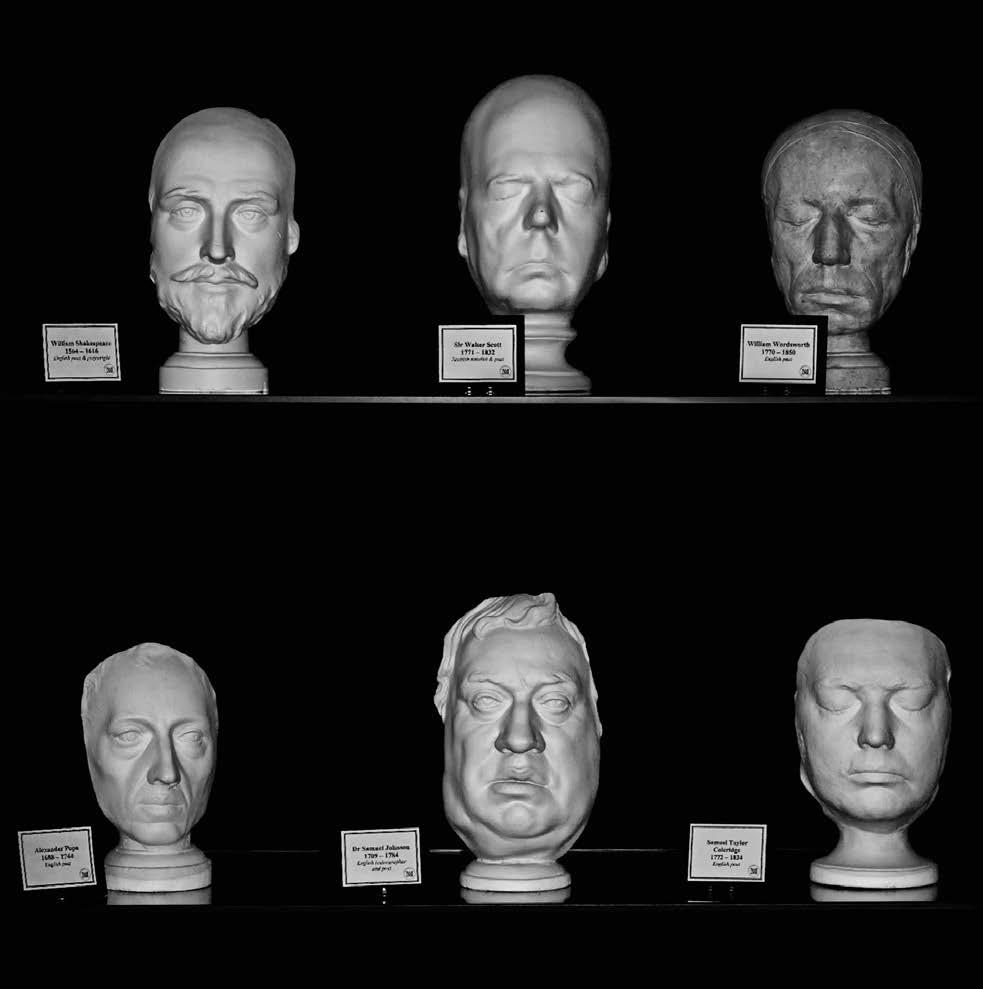

CLOCKWISE, FROM RIGHT:

The University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum has a collection of more than 40 death masks, including several famous names; another phrenology head marking out the skull’s subsections; a phrenological diagram listing definitions of the various different areas of the human skull, published in c.1859; Franz Joseph Gall, German neuroanatomist and founder of phrenology

that undergirded the way phrenology ordered the brain is faulty, it was a stepping-stone to later 19th-century discoveries in cerebral localisation.”

“Phrenology also played a role in the scientific racism that burgeoned in the 19th century. The way phrenologists grouped individuals by head shape and size proved a gateway for later race sciences like craniometrics.”

According to phrenology, the brain’s 27 different organs created the personality of an individual. Some organs were good or bad qualities, others marked creativity, language or morality. While some of these facets were general, others were more specific.

Phrenology researched an individual’s ‘ambition and vanity’, their ‘mechanical skill’, ‘aptness to receive an education’, ‘recollection of individuals’ and even their ability to mimic, among many other traits. Each skull was measured against another. The comparison would highlight larger or smaller ‘organs’, which in turn might signify the consistent character of either a good or bad person.

In a book written by Thomas Stone Esq, published in 1829, Observations on the Phrenological Development Burke, Hare, and Other Atrocious Murderers: Measurements of the Heads of the Most Notorious Thieves and read before the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, the author raises the interesting question: “Is it possible to distinguish the crania of murderers from other crania, by the phrenological indications attributed to them?” That question of course laid bare the entire conjecture of phrenology.

The author, however, did not completely agree with the phrenologists and wrote, rather scathingly, that “the production of a single anti-phrenology fact would be

sufficient to overturn the whole theory... they would at once discover that their system is no more than the ‘baseless fabric of a vision’ and as false as any other superstition”!

One particular example of a phrenological study was the notorious William Burke of Burke and Hare, who terrorised Edinburgh with their murders. According to the Warren Anatomical Museum, part of the Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library of Medicine, after his execution in 1829, Burke was examined by local phrenologists and a death mask was created by George Combe himself, which is today in the care of the museum.

Dominic Hall added, “The case of Burke would have been an excellent example of the phrenological trait of destructiveness given the infamy of the case. Phrenologists definitely did hope that the practice could be predictive, and that by studying heads and casts one could spot and stop future William Burkes.”

Despite its controversy, however, phrenology became a study that gained widespread interest, if only for a time, largely due to the tireless work of the Combe brothers. Such was their publicity that the Scottish society reached the attention of the monarchy and reportedly even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert engaged George Combe in order to examine their young childrens’ skulls.

Phrenology was often referenced by Victorian authors such as Scotsman Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who wrote in the Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), “... Mr Holmes... A cast of your skull, sir, until the original is available, would be an ornament to any anthropological museum...”

Today, phrenology and the Edinburgh Phrenological Society may have slipped into just another almost forgotten chapter of Scotland’s interesting medical history. However, at a time when scientific understanding was in its infancy – and the Victorians devoured anything to do with the criminal and the curious – phrenology provided an interesting bridge between modern-day advancements and the search for answers to questions about the most complex organ of all: the mind. S