9 minute read

Life in a fishbowl

Words and photos by PAUL STAFFORD

Huddled at the edge of the River Dee, the former fishing village of Footdee provides a quirky splash of colour in the face of Aberdeen’s encroaching heavy industry

PREVIOUS PAGE AND THIS PAGE, TOP LEFT AND

RIGHT: The defiant spirit of the Footdee community is emblazoned across their doors, windows and walls

BELOW RIGHT:

The local oil industry’s infrastructure encroaches on Footdee to this day

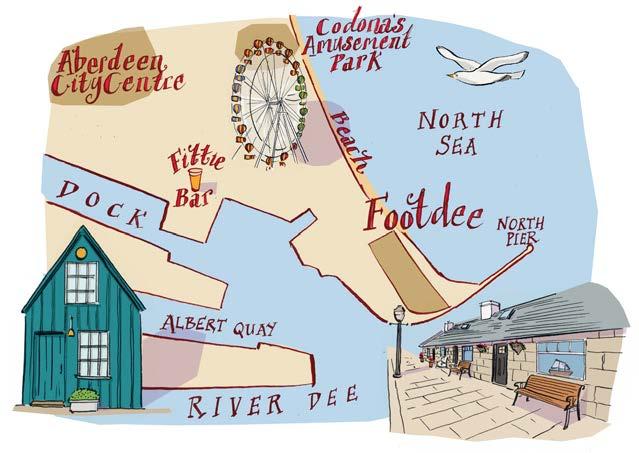

ILLUSTRATION: © MICHAEL A HILL Aberdeen has, somewhat unfairly, acquired a reputation over the years as a grey, dreary place. Unable to shake this image and despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, artistic Aberdonians have increasingly made their creative endeavours public-facing.

A visit to Scotland’s third largest city usually includes a trip to Aberdeen Art Gallery, an unmissable celebration of art from around the city and further afield. And in the charming neighbourhood of Footdee (affectionately named ‘Fittie’ by locals), the subtler, artisanal sprinkling of creative flair has been turning heads for some time.

Like any self-respecting modern city, Aberdeen has street art aplenty. Be it the enlivening artworks of Jopp’s Lane or Harriet Street, you’ll find big, bold murals exploring the city’s often challenging relationship with both land and sea. Many of the murals were painted by British street artists, although there’s a strong global presence in paint around the city centre too, with some creatives coming from as far away as Argentina to complete their artwork on the granite walls.

Footdee however, seems a world away from the global melting pot that central Aberdeen has become in the long wake of significant oil discoveries offshore starting in the 1960s. The art you see dotted around the neighbourhood was often created by residents. It doesn’t exist as a show of flair to the outside world; its purpose is to brighten up a small, resilient community that has survived despite the encroaching oil industry.

“Our sister village Torry didn’t survive. It was razed to create space for the oil tankers,” said Pauline Brown, who is Chair of the Fittie Community Development Trust, but who asked to speak with me solely as a proud Fittie resident.

She was quick to dispel any notion of divine providence. “I think Footdee survived just because it wasn’t in the way.”

In the 1970s, Aberdeen Harbour’s spacious docks and solid infrastructure made it the favoured choice as a hub for the offshore oil industry, which quickly commandeered the entire port and everything around it. Given that the north side of the River Dee hosted many of the city centre’s historic buildings, it was the smaller settlements on the south side, including Old Torry, that were condemned to the bulldozers instead, making way for dry docks and warehouses in service of capricious hydrocarbons.

The walk from the city centre to Footdee passes through one long, continuous industrial park. Most of Footdee was razed around the same time as Old Torry. For example, the land around York Street would once have held the homes of fisher folk, fronted by whalebone arches. In their place now exist quays, yards filled with rusting old anchors and spare parts, and rows of huge blue or white oil reservoirs, which loom ominously over the village like a viscous threat.

FISH TOWN

The surviving section of Footdee, also known as the Fittie Squares, was arguably the most unique bit of the neighbourhood. It looks as though it has no business being there still, hemmed in on all sides by either water or heavy industry. This small cluster of pleasant, terraced homes was built later than the rest of Footdee. The first historical recognition of its existence is on a map dated 1828, which labels the area ‘Fish Town’. It’s not clear when that name fell out of usage.

Designed by the architect John Smith, the houses are laid out in squat rows ranged around two communal squares. The frontages all face inwards, immediately engendering a sense of community around the shared lawns, where inhabitants still hang their washing out to dry.

“The original design of the squares was to protect the houses from the elements,” said Brown. And who would have been better positioned to understand the ferocity of the North Sea’s regular wintry squalls than the fisherfolk who earned a living from the sea?

From the outside, Footdee has a hardy, uninviting carapace. What is surprising however, is the delicate beauty within the squares, as though the thick, outer seawall can entirely protect an interior that includes various wooden or corrugated metal sheds from the elements.

It’s hard to know for sure now, with such scant historical documentation available, whether the ‘Fittie fowk,’ as they were oft called, were as insular as some records made them out to be. Perhaps it was a misunderstanding derived from the uninviting exterior of Footdee by those who had never ventured in, but they had a reputation for being quite singular, even speaking their own strong dialect.

While not a great deal is known about the inhabitants of early Footdee, it is thought that life and fish were inseparable. Children were said to have been prevented from schooling in order to learn the trade early on. Primogeniture prevailed, so that fishing boats passed down from father to the first son, keeping business in the family.

An exception to this impenetrable lifestyle is a poem attributed to former Footdee resident Ann Allardyce (17771857), who only lived for part of her life in the neighbourhood before moving away.

We brak nar breid o’ idlecy

Doon by in Fittie Square;

A’ nicht oor men toil on the sea

An’ wives maun dee their share;

Sae fan the boats come laden in

I tak’ my fish tae toon,

ABOVE:

The ‘Fittie Squares’ are protected from the elements by thick seawalls An’ comin’ back wi’ empty creel

Tae bait the lines set doon.

The poem neatly presents the dynamic of married life for the hard-working Fittie fowk: husbands would haul their catch in from the sea; wives would sell the catch in town and then return home to bait the lines ready for the next day’s fishing. A well-oiled family unit.

A FITTIE REFIT

As in many places along the Scottish coast, fishing declined immeasurably in the 20th century, leading to the demise of its communities. “The demography has really changed. It used to be fisher folk here, and then a lot of people either died or moved away as they moved up in the world, or emigrated to places like America, but that old community they left doesn’t really exist anymore,” explained Brown.

The clamour of families that once reverberated around Footdee’s inner courtyards is rarely heard now. “Houses in Fittie used to cost a fortune but now it’s hard to get rid of them,” said Brown. “If you couldn’t smell the salt-tinged air or hear the gulls, you might not even be sure this was a seaside neighbourhood anymore, let alone a former fishing community. But one thing Footdee has in spades is creativity.”

“Joyce Cairns, president of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, has a home here. So, she was the original creative force in the village. And that has inspired others to do artistic things,” explained Brown. These artistic flourishes are the true source of Footdee’s charisma today.

When I first arrived in the neighbourhood it was golden hour, with the warm sun casting elongated shadows over the squares. There were very few people about, but with each house’s windows all facing inwards, I felt like an impostor, being observed by an attentive compound eye. There were no art displays or installations, like with the city centre murals. Instead, I came across dozens of little flourishes of creativity that felt simultaneously eccentric and cosy, like curated flotsam: a fat little porcelain blackbird perched on a wall; an old pump gushing water through a lion’s mouth; three floating sailor heads named Tom, Dick, and Harry; a mermaid mosaic; a Buddha faced off with a gargoyle; and a blue wooden house covered in mosaic salamanders. So much of Footdee was touched by whimsy. It was a soulful affront to the oil industry that had parked up on their doorstep. A quiet ode to patience and resilience. There was nothing carnivalesque about it at all. In fact, despite the open-plan layout, I felt as though I shouldn’t have been there. The neighbourhood was just too personal to afford the residents privacy from my prying intrigue. And that is Footdee’s latest existential crisis.

“There’s no fundamental code of conduct or basic principles for visitors. We’re becoming very beleaguered in the high season, with several tour buses a day of up to 80 people each coming through the village. Thirty years ago, you used to get the occasional couple coming or a niche tour. Now it’s full tilt with tour guides in kilts,” said Brown. “It feels like visitors think they’re at a theme park, traipsing through and looking at us as if we are a bunch of bonobos.”

It’s difficult to even imagine 80 people milling around this small space. There are no cafes or pubs, shops, or museums within the Fittie Squares (thought the Fittie bar is not far away), in fact no building at all into which visitors can filter, only the two intimate squares, fronted by private homes. The pity is that the creativity of the community has fallen prey to the Instagram generation. “But it’s not a case of us and them at all,” said Brown. “We are just trying to find a way to make it work. To make it manageable.”

The current lack of public facilities or even sufficient refuse receptacles is making life for today’s Fittie fowk difficult to say the least.

Yet if there was ever a resilient community capable of weathering a storm, it is one built by North Sea fisherfolk. With community creativity in abundance, there are some signs of positive change on the horizon.“The [Fittie] Trust is a secular community initiative that has bought the old gospel hall and is refurbishing it to make a community facility. We bought it through the Community Empowerment Act of 2015 via Aberdeen Council,” said Brown.

It’ll be the first time in a while that the increasingly disparate community has had a focal point, allowing them to gather for things like special events. As time has shown here before, with a strong sense of community and a little good fortune, a village like Footdee can endure whatever changes may take place around it. And if nothing else, Footdee continues to prove that Aberdeen is anything but grey and dreary. S