3 minute read

Last Word Katherine Swift on the garden imagery in the patterns of Persian carpets.

Paradise Underfoot

Take a closer look at the patterns woven into Persian carpets, says Katherine Swift, and you may find a representation of the paradisal walled desert garden

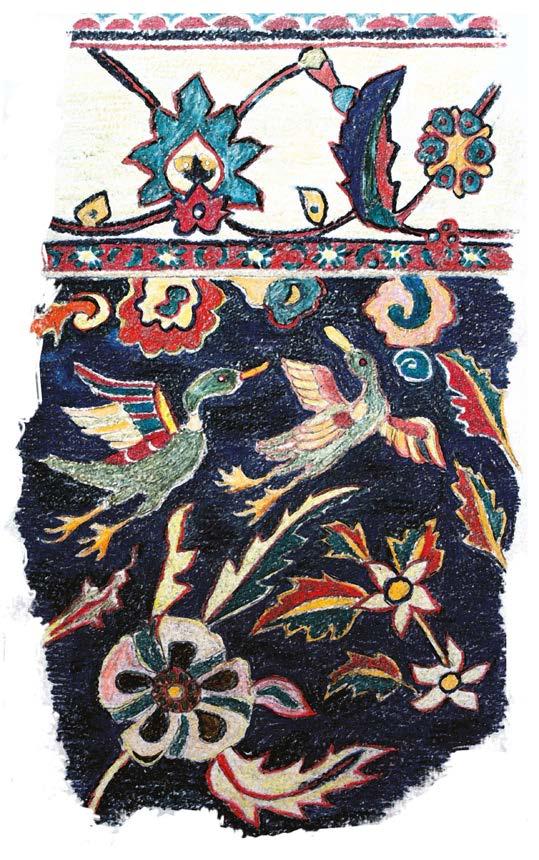

There is something delicious about walking back to the house in a winter dusk, when all in the garden is dreary, and seeing the house with the lights on – the multicoloured spines of books lining the walls, the brilliant green leaves of orange trees overwintering, the old Persian carpet on the fl oor. The carpet was made in about 1900, in eastern Iran, and is what is called a tribal or village rug. Dark blue, with a brick-red border and stylised images of fl owers and trees, animals and birds, it is startling in one particular respect: the slanting, asymmetrical grid of brighter blue channels that move across the dark blue ground, exploding here and there into colour. Irrigation channels, perhaps, bringing water and life to what is very clearly a walled garden.

The dream of a walled garden set in a parched landscape has possessed the human imagination for millennia. It is a motif that recurs in all three of the great religions of the ancient Near East – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – and is based on the reality of ancient Persian walled gardens. With water brought in by a system of meticulously engineered qanats (underground gravity-fed channels that carried snow-melt from the foothills of the mountains to the villages and gardens of the plain), trees planted for shade, and an abundance of fruit and fl owers, these gardens were unlike anything that had been seen in Europe at the time. They were admired by invading Greeks in the 4th century BC, copied by the fi rst-century Romans on their estates in Italy, and ultimately inherited by invading Arabs in the 7th century. The Greeks called them paradeisos, from the Persian pairi (around) and daeza, (a wall). Paradise – the word that Greek scholars later used in their translation of

The Wagner carpet, is touring the museums of America, like an eighth wonder of the world

the Bible to render the Hebrew word for the garden planted by God in Eden.

Gardens were an enormously important part of Persian culture. One 6th-century Persian king went so far as to commission a carpet that was 90 feet square to represent his garden in spring, as consolation for its lack in winter. ‘The Springtime of Chosroes’, as it was known, was probably woven in situ, in the royal palace of Ctesiphon, where it was discovered by invading Arabs in AD 636.

Following the Arab conquest of Persia, and the conversion of the Persian peoples to Islam, the Persian desert garden acquired a further spiritual dimension as a foretaste of the heaven to come – the chahar bagh, or quadrilateral garden, divided by four fl owing watercourses, recalling the four rivers of Eden, as described in the Qur’an – and it was in this form that the Persian garden was carried to North Africa, Spain, Central Asia and India, as the Islamic empire expanded. One of the oldest and fi nest garden carpets to survive today is the Wagner carpet, in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow. The Burrell is currently closed for refurbishment, and the carpet has been touring the great museums of North America, like an eighth wonder of the world. Because of its size (530.9cm in height and 431.8cm in width, or 17.5ft by just over 14ft), although only a fraction of the reputed size of ‘The Springtime of Chosroes’, the Wagner carpet has rarely been exhibited at home, and has spent much of its time in storage. But when the Burrell reopens in March 2022, it is hoped it will be on display in the new galleries. In the meantime, in the middle of dreary winter, I shall console myself by gazing upon my own little slice of irrigated Paradise. ■

Rupert Till

S C U L P T O R

SCULPTURES IN WIRE

t +44 (0) 7921 771284 e rupert@ruperttill.com w r up er ttil l.com