9 minute read

Discover London’s finest stately homes, conveniently clustered together in the city’s westernmost reaches

Beside the SEASIDE

Sea, sand and (sometimes) sun: the great British seaside holiday is a much-loved and always evolving tradition

WORDS NEIL JONES

Medieval pilgrims prayed at a shrine at Winchester Cathedral

Relaxing in a colourful deckchair, sand between your toes. Rock-pooling, beachcombing, swimming and surfing. The whiff of fish and chips drifting along the promenade is irresistible, and who cares if the candyfloss is sticky?

As the music hall song would have it, we “do like to be beside the seaside”; indeed a love of bathing in the briny and building sandcastles seems written into our DNA. Yet, surprisingly for an island nation, we were rather slow to embrace the leisure potential of our coast.

The great British seaside holiday only really began in the 18th century as people slowly moved from ‘taking the waters’ for their health at inland spas to the newly fashionable alternative of bathing in the sea. Scarborough on the Yorkshire coast, by virtue of already having been a mineral-spa town, styles itself Britain’s original seaside resort, but it was the Dorset town of Weymouth that reaped a notable royal seal of approval when King George III, following medical advice that a dip in the sea could help alleviate his ailments, spent 14 summers here between 1789 and 1805.

Conveyed into the water in a bathing machine (like a beach hut on wheels in which people could undress hidden from public gaze), George bravely took the plunge. “Think but of the surprise of His Majesty,” a member of the royal party recorded, “when, the first time of his bathing, he had no sooner popped his royal head under water than a band of music, concealed in a neighbouring machine, struck up ‘God save great George our King’.”

FUNKYFOODLONDON - PAUL WILLIAMS/STUART BLACK/IMAGEBROKER/TRAVELLINGLIGHT/ALAMY © PHOTOS:

Clockwise, from top left: Traditional beach huts at Southwold, Suffolk; Beer Beach, Devon; Weymouth, Dorset; Saltburn Cliff Tramway, North Yorkshire

Clockwise, from top left: Statue of King George III in Weymouth; Punch and Judy in Brighton; Blackpool Central Pier, Lancashire; Glamorgan Heritage Coast, Wales

WILF DOYLE/ALAMY/MARK SYKES/TRAVEL PIX COLLECTION/AWL IMAGES/BILLY STOCK/4CORNERS © PHOTOS:

You can see a replica of the royal bathing machine on Weymouth’s esplanade, where handsome Georgian terraces and a statue to the king bear testament to the early days of the resort, still popular thanks to its wide bay and fine sands beloved of bucket-and-spadewielding families. Perhaps the most stunning royal seaside architectural legacy, however, is to be found along the coast at Brighton, where George’s son, later George IV, was advised by physicians to try seawater treatments; he loved his stays so much he built the exotic pleasure palace that is the Royal Pavilion.

At first bathing was generally a naked activity – ‘modesty hoods’ covering the end of the bathing machine enabled users (aided by attendants called dippers) to slip into the water unseen. Later, even when people donned voluminous costumes, some places segregated the sexes onto separate beaches.

From the mid-19th century a growing railway network, combined with the Bank Holidays Act (1871, England, Wales, Ireland), put seaside resorts on the map for the day-tripping masses, who eagerly made the most of their new public holidays by leaping aboard excursions laid on by canny train operators. While the health benefits of seawater and ozone were still a draw, it was the seaside as a place of entertainment that now grabbed the imagination.

Piers sprang up and with them the carefree blend of the posh, pricy and sedate with the vulgar, cheap and racy that became a distinctive feature (and attraction) of the seaside experience. Serving as landing stages for visitors arriving by paddle steamer, piers also allowed landlubbers the novelty of ‘walking on water’ – “Here for the sum of twopence you can go out to sea and pace this vast deck without need of a basin,” the Victorian novelist William Makepeace Thackeray rejoiced of Brighton’s since-vanished Chain Pier (you can still enjoy breathtaking views from the Palace Pier as well as quite literally breathtaking funfair rides).

Not content to pocket landing dues at one end and pedestrian tolls at the other, pier operators soon lightened strollers’ pockets in between by means of food kiosks, shops and musical performers. Among the 70 or so piers built in four decades of boom from the 1860s, Teignmouth in Devon (opened 1867) stole a march with the first coin-operated ‘What the Butler Saw’ peep-show machines.

Meanwhile Blackpool, Bournemouth and Brighton boasted three piers apiece, each catering for different tastes, and the Indian Pavilion on Blackpool North Pier spawned a veritable rash of pavilion-building around the country where concerts, balls and end-ofpier shows could be staged. Indeed Blackpool, still with three piers (filled with modern thrill-seeker rides, shows and arcades), has been at the forefront of ever bigger, brighter (and brasher) entertainments from the outset, with its Tower (1894), ballroom, circus, Pleasure Beach of white-knuckle adventures, and six miles of world-famous Illuminations. In the 1890s the resort was also among the first to heavily market that jaw-breaking favourite, seaside rock.

Above: Princess Gardens and Pavilion on Torquay Seafront, part of the English Riviera Below: Durdle Door, a natural landmark on Dorset's Jurassic Coast

NAGELESTOCK.COM/ALAMY/ISTOCK/GETTY © PHOTOS:

Elegant promenades were another feature of seaside resorts that grew up in Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian times, and seafronts like the palm-lined promenade of Torquay on ‘England’s Riviera’ entice to this day. Bandstands sent music floating through the air – the current one in Eastbourne, built in 1934, is still going strong with the claim to be “the busiest bandstand on planet Earth”.

To avoid unwarranted exertions on your coastal excursion – past or present – you might take a cliff lift to the seafront: constructed in 1912 and measuring just 130ft, the one at Southend-on-Sea is Britain’s shortest funicular railway (the resort also boasts the world’s longest pier, at 7,080ft). At Saltburn you can gently descend in Britain’s oldest working waterbalanced cliff tramway (1884).

Once on the seafront, all manner of giddy delights awaited – perhaps a ride along the beach on a donkey, a tradition begun in the late Victorian era, or the spectacle of a knockabout Punch and Judy show, rooted in Italian commedia dell’arte and given a British seaside twist. There were showmen aplenty, like stunt diver ‘Professor Davenport’ who thrilled Edwardian onlookers at Hastings Pier by jumping into the sea inside a burning sack; reports of his wider repertoire enthused: “he dives smoking a cigar [...] which he brings up again alight. He can also dive from a bicycle from a flying trapeze.”

Buttoned-up ladies and gents and factory workers alike succumbed to the collar-loosening effects of the seaside. As the 20th century unfolded, trouser legs were well and truly rolled up and heads sported knotted hankies, while cheap and cheerful souvenirs and the sending of saucy postcards became de rigueur. There was always the knobbly-knees competition to win at a seaside holiday camp and, thankfully, swimwear progressed from droopy wool-knitted styles to more water-suitable numbers.

Package holidays to sunnier overseas climes dented the British seaside holiday trade in the latter half of the 20th century but tides turned again with the rise of the staycation: bolstered by a doughty British spirit unafraid of the occasional rain-shower and by the sheer diversity of seaside escapes within easy reach, always evolving while always offering that sense of joyous freedom at the heart of their allure.

Thus today you can enjoy top surfing experiences at Newquay in Cornwall, traditional bucket-and-spade holidays from Bournemouth to Tenby, the bohemian buzz of Brighton and the candy-coloured beach-hut charms of Southwold. Winner of ‘Pier of the Year 2020’, Clacton in Essex is Europe’s largest pleasure pier, while Margate’s Dreamland channels retro amusement-park thrills. You can walk in the footsteps of dinosaurs on Dorset’s craggy Jurassic Coast or get away from it all along the Glamorgan Heritage Coast or the expansive sands and dunes of Northumberland. All these – and everything in between – are why we still like to be beside the seaside.

Best of BOTH WORLDS

Explore England’s coast and countryside without lifting a nger with English Cottage Vacation, a new breed of luxury holiday

English Cottage Vacation is far more than your standard, luxury catered cottage; it’s an “appanage”, a term that hosts Nathan and Laura Kurton use to define their new holiday concept’s special attributes.

An “appanage” is tailor-made, ultra-luxurious, completely private, and has one all-inclusive price. To top it off, it’s the level of care and attention to detail that you’ll experience here, which elevates the “appanage” above other luxury options. This is where the traditional comfort and elegance of the English nation meets exceptional hospitality.

Well Cottage itself, which sleeps six, is an 18th-century, thatched gem, ideally placed in the small hamlet of Bedchester. Located on the outskirts of both the Cranborne Chase and Dorset Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, it is within easy reach of both the English seaside and beautiful landlocked landscapes. Head southwest and you’ll Meanwhile Nathan is your personal chauffeur, tour guide, waiter and barman.

Well Cottage really does offer the best of both worlds: brilliant access to both land and sea, while combining superlative service - usually the reserve of charter yachts and five-star hotels - with the flexibility and privacy that comes with selfcontained holiday accommodation. Thanks to Nathan and Laura’s passion for and knowledge of their country, your English Cottage Vacation will be truly unforgettable.

find yourself on Dorset’s famous Jurassic Coast, with its skyscraper-high cliffs, sweeping sandy beaches and 185 million years of archaeological history. Meanwhile, stay inland and you can explore Downton Abbey’s real-life double Highclere Castle, Longleat House and Gardens, Salisbury Cathedral and the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site among many other attractions.

While you have complete control over your itinerary and how you spend your time, you won’t have to do anything for yourself. Having spent 10 years working on high-end, luxury charter yachts, Nathan and Laura decided to anchor the quality of their seafaring hospitality expertise to their homeland. As ‘live in hosts’, Laura is your housemaid and personal chef, providing gourmet dining for three (or more) meals of the day, with drinks and snacks to suit every occasion available on demand.

For more information, please visit www. englishcottagevacation.com or contact Nathan and Laura at info@englishcottagevacation.com.

Coin of the Realm

Fifty years ago Britain adopted decimal coinage: a momentous step that was first proposed centuries earlier. From the beginnings of minting to present-day pounds and pence, we tell the eventful story of Britain’s coinage

WORDS NEIL JONES

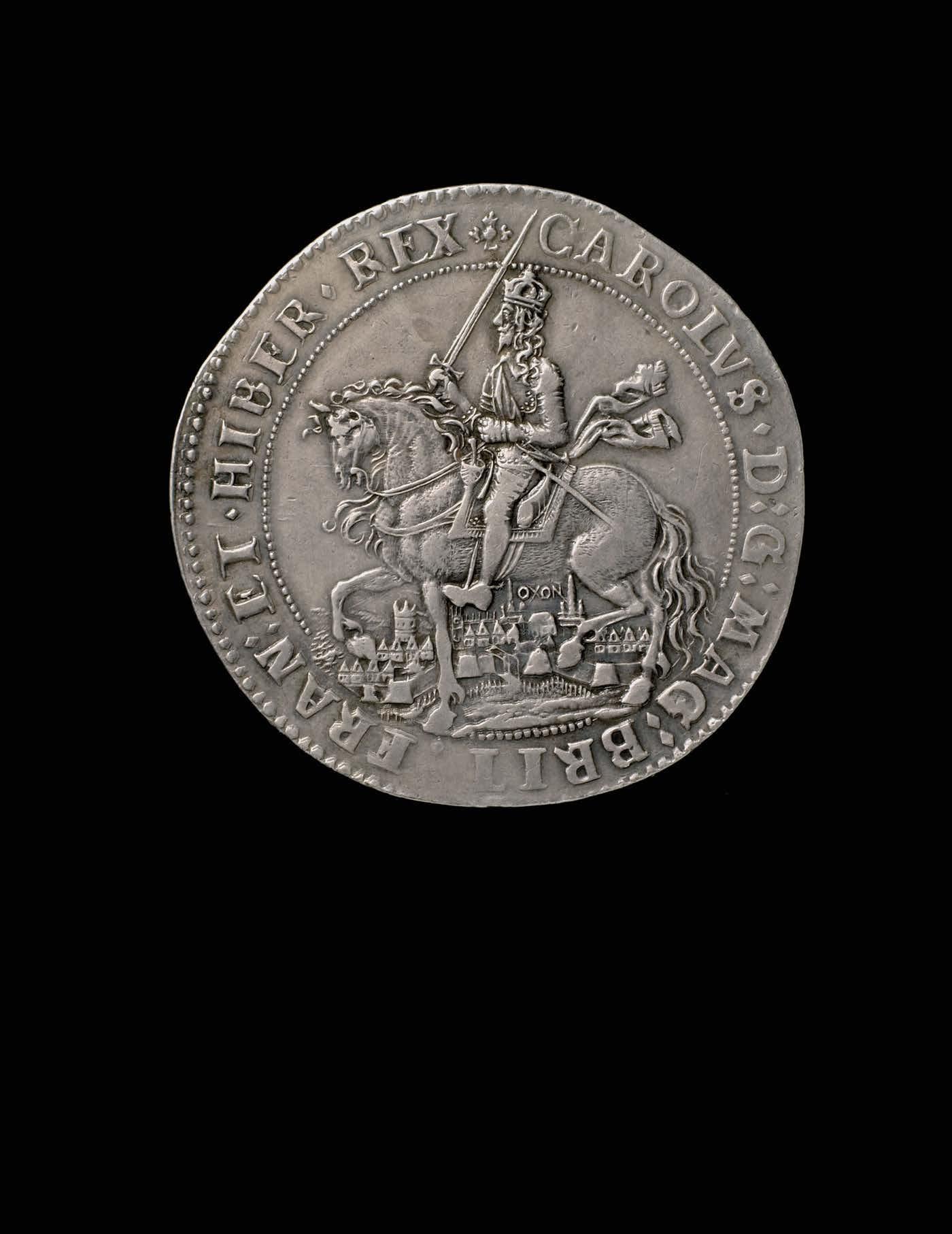

The Oxford Crown depicts Charles I riding through the Oxford cityscape, 1644